Growing up outside Washington, D.C., my dad often took my sisters and me on weekend “field trips” to the Smithsonian museums. A favorite was the National Museum of American History, where every visit began the same way: by paying our respects to Dorothy’s ruby slippers. They were bewitching, and absolutely astonishing in their tangibility. It seemed incredible that something I knew to be make-believe could somehow also actually exist, and just six inches from my nose at that.

When the Smithsonian announced the slippers would be loaned to London’s Victoria and Albert Museum for four weeks in 2012, I was surprised to find myself a little anxious over their first trip overseas. Those shoes were wrapped in layers of childhood memories and wonder, and the idea of their leaving home—my home—felt strangely akin to a significant personal event.

As it turns out, I was not the only one. The slippers’ journey was written up in news outlets from Seattle to Boston, Louisville to Phoenix, and Winnipeg to Sydney. There were pieces in Forbes, in Vogue, The Wall Street Journal, and The Huffington Post. The Smithsonian even planned a special departure ceremony for the shoes, one of their most-visited objects on display. Their eventual homecoming to D.C. was triumphant, a moment captured succinctly, but gleefully, by The Washington Post: “They’re back!”

Those shoes were wrapped in layers of childhood memories and wonder, and the idea of their leaving home—my home—felt strangely akin to a significant personal event.

It was a relief, it would seem, for all of us. Whether we came to the story through the original 1900 children’s book by L. Frank Baum, or through the 1939 film adaption with Judy Garland, The Wizard of Oz has become a part of our shared emotional property, one that has entrenched itself deep within our collective personal and cultural psyche. Filled with wonder and danger, friendship and foes, millions of people throughout the world have developed meaningful, memorable connections with the story, experiences which are often amplified by the nostalgic lens of childhood. Few mythological stories have become so mythologized as Oz.

• • •

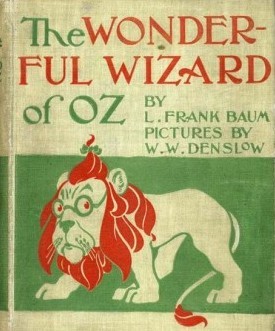

Of course, Baum could not have predicted how mass media would one day multiply the influence of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, as it was originally titled—an impossible task, given that moving pictures were barely in their infancy when it was written. But regardless of the phenomenon his story would one day become, his immediate impact on the American imagination was significant.

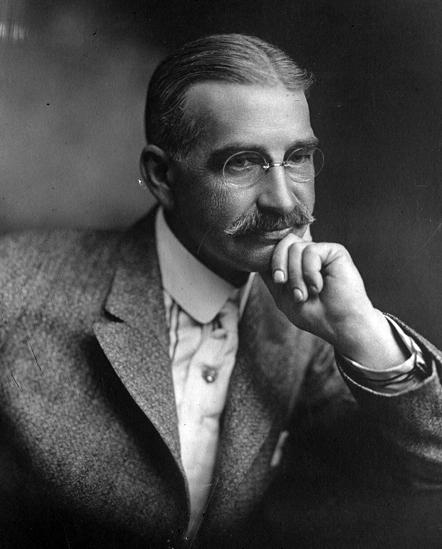

L. Frank Baum

From the start, Baum seemed to sense that he had a hit on his hands. He went so far as to frame the pencil stub with which he wrote the manuscript even before it was published. This was a bold stroke of hubris, especially considering how many failed business enterprises Baum had launched through the years: his turns as a newspaper publisher, china salesman, theater director, and chicken farmer had all ended dismally.

But as the father of four young sons, Baum was an adept and practiced storyteller, and was urged by his mother-in-law, suffragist Matilda Gage, to try his hand at children’s writing. She even suggested a topic: a cyclone, that might blow in by way of North Dakota.

In the end, he honored her career advice, publishing Mother Goose in Prose in 1897, By the Candelabra’s Glare in 1898, and Father Goose: His Book in 1899. All did well, but none came close to the achievements of Oz. Even those raised by wolves know the premise by now: a young girl named Dorothy Gale finds herself in an enchanted land after a cyclone whisks her and her little dog Toto from their Kansas farm. As she journeys down the yellow brick road to ask the great and powerful Wizard of Oz to help her return home, she acquires three unusual traveling companions, each of whom sets off to ask the Wizard for something that they lack: the scarecrow, a brain; the tin woodman, a heart; and the cowardly lion, a dash of courage.

Oz was more than just a bestselling sensation. In his introduction to Oz, Baum wrote that the time had come for a newer set of fairy tales, one which eliminates “all the horrible and blood-curdling incidents devised by their authors to point a fearsome moral to each tale.”

The work was an immediate success, both critically and commercially. In an October 1900 review, The New York Times wrote that “it will indeed be strange if there be a normal child who will not enjoy the story.” As if to prove the reviewer’s point, the first edition’s 10,000 copies quickly sold out. Interest was so high, and demand for more was so great, that Baum parlayed the book into an empire, writing 13 subsequent books in the Oz series that included not only Dorothy returning to Oz several times but also, in one novel (The Emerald City of Oz), being joined by Aunt Em and Uncle Henry. Also, the Scarecrow, the Cowardly Lion, the Tin Woodman, and Glinda the Good Witch were featured in their own Oz books. Baum also introduced memorable new characters in the series including the Wheelies; Tik-Tok, the mechanical man; the Hungry Tiger; Scraps the Patchwork Girl; Jack Pumpkinhead; and the Nome King. After Baum’s death, the Oz series has continued with writers such as John R. Neill (one of Baum’s illustrators for the original series), Ruth Plumly Thompson, Jack Snow, and James C. Wallace II.

But Oz was more than just a bestselling sensation. In his introduction to Oz, Baum wrote that the time had come for a newer set of fairy tales, one which eliminates “all the horrible and blood-curdling incidents devised by their authors to point a fearsome moral to each tale.” He reasons that teaching morality is the job of modern education, freeing literature from such constraints. And so, “The story of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was written solely to please children of today. It aspires to being a modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heartaches and nightmares are left out.” With these words, and in the pages that followed, Baum created what was essentially the first American fairytale, not just written by an American author, but firmly rooted on U.S. soil. Although there had been a few fantasy stories published in this country, such as The Wonderful Stories of Fuz-Buz the Fly and Mother Grabem the Spider (S. Weir Mitchell, 1867), none were so defiantly American as Oz.

Before the 19th century, books written for American children were more guides than stories, designed to impress religious, moral, and practical values on formative minds still susceptible to corruption. But as the 19th century progressed, childhood began to be viewed less as preparation for adulthood and more as a distinct phase of life, replete with its own tastes, humors, difficulties, and longings. Literature evolved accordingly, and books began to appear that spoke, rather than sermonized, to young audiences. Horatio Alger’s popular books, such as Ragged Dick (1868) and Luck and Pluck (1869), were highly didactic yet also entertaining to young readers. Mark Twain was wildly popular with his “bad boy” books, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), and Louisa May Alcott was one of the first authors to identify with adolescent growing pains with her novels Little Women (1868) and its sequels Little Men (1871)and Jo’s Boys (1886). Although these latter books could fuel dreams of adventure or strike emotional chords, they did not invent new worlds or creatures, or ask children to suspend their beliefs as they probed deep into their imaginations.

For magic and fantasy, America had traditionally had to look elsewhere, mainly to Europe. There were the fairytales of the Brothers Grimm, Charles Perrault, and Hans Christian Andersen., But it was Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland(1865) , that truly launched the Golden Age of Children’s Literature of the latter part of the 19th century and the early 20th century which produced such renowned children’s classics as Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson (1883), The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame (1908), The Jungle Books by Rudyard Kipling (1894, 1895), Peter Pan by J. M. Barrie (play 1904, novel 1911), and The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1911). But Baum gave young American minds a source of otherworldly adventures much closer to home. While many classic fairytales have vague, indeterminate settings, Baum uses the first few pages of Oz to situate readers squarely amid the gray, sun-baked Kansas prairie, where “even the grass was not green, for the sun had burned the tops of the long blades until they were the same gray color to be seen everywhere.” (Baum visited Kansas in the dead of winter as a young man, which might explain his negative outlook.) It is not the most appealing portrait of American life, but it suggests that magic could occur even in the most hardscrabble, nondescript spots in the country. There was no need to live in proximity of a castle, or an enchanted forest; you could live right in the middle of the parched Midwestern plains and still encounter the most fantastic of fantasies.

Nor did you need to be a princess, or possess great beauty. Our heroine was a plucky but ordinary little girl, who never faltered for an instant in her quest to return home. As her actions and those of her traveling companions reveal along the journey, each character already possesses their supposed deficiencies, and Dorothy alone holds the power to see her way back to Kansas. There is no need for wizards or benevolent witches after all: each of us carries all the gifts we need within us, and bears the potential to make something of ourselves. In its endorsement of individualism, the story was as American as they came, and it marked a milestone moment in the country’s growing canon of children’s literature.

• • •

As it turned out, the United States was ready in full to embrace an American fantasy as its own. Like every good fairytale, Oz lent itself to reinterpretation, and within a few years of the book’s publication, it was retold as three silent films and a stage musical. But it wasn’t until The Wizard of Oz exploded onscreen as a Technicolor marvel in 1939 that the story’s fate was sealed within the country’s cultural playbook. It has since become one of the few movies ingrained in the childhoods of successive generations, aided by several theatrical re-releases, and more importantly, frequent network broadcasts, which were often major household events before the dawn of the VCR. The first, in 1956, drew 45 million viewers, and its success led to annual television broadcasts beginning in 1959.

There is no need for wizards or benevolent witches after all: each of us carries all the gifts we need within us, and bears the potential to make something of ourselves.

Today, the Library of Congress estimates that The Wizard of Oz has been seen by more viewers than any other movie in history. As such, lines like “Toto, I don’t think we’re in Kansas anymore” and “I’ll get you my pretty, and your little dog too” seem second nature, and it’s commonplace to know every lyric of the Harold Arlen/ “Yip” Harburg tune “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” voted the greatest movie song of all time by the American Film Institute. As Baum biographer Evan Schwartz wrote in his 2009 book Finding Oz: How L. Frank Baum Discovered the Great American Story, “The movie kept attracting a cultlike following, only virtually everyone was in the cult.”

Meanwhile, our fascination with Oz continues to grow. Now 115 years after the book first appeared, Oz continues to spawn prequels, sequels, and retellings, insinuating itself deeper into global culture with every iteration. Among the most notable have been The Wiz, the 1978 film version of the successful Broadway musical starring Diana Ross and Michael Jackson; the 1985 non-musical film, Return to Oz; Wicked, Gregory Maguire’s 1995 novel that became a Tony Award-winning Broadway smash; the 2005 film The Muppets’ Wizard of Oz; the 2013 film Oz the Great and Powerful, starring James Franco and the animated musical Legends of Oz: Dorothy’s Return. There have even been reports that The Wizard of Oz will be NBC’s next live musical event, following on the heels of successful live broadcasts of The Sound of Music and Peter Pan. There are organizations and conventions devoted to the appreciation of Oz, and you don’t have to look further than Dunkin’ Donuts’ Munchkin bites to see the story’s linguistic impact.

Ironically, this tale was written expressly “to please children of today” has become the subject of countless theories about its deeper meaning. Perhaps the best-known portrays Oz as a parable of American populism and the monetary crisis of 1896, which was concocted by a high school history teacher as a teaching aid for his students. The first edition of Baum’s classic that featured a learned interpretation was historian Russel B. Nye’s The Wizard of Oz and Who He Was (1957). Ranjit S. Dighe’s The Historian’s Wizard of Oz: Reading L. Frank Baum’s Classic as a Political and Monetary Allegory (2002) is the latest account of the scholarly interpretations of Oz. Others have proposed that the journey along the yellow brick road actually represents our personal journey toward spiritual enlightenment, while some have seen the book—and its witches—as glaringly pagan, causing occasional bans in school libraries. There are still others who theorize that the book’s enslaved Winkie population represents the mistreatment of Native Americans, which stems from an editorial Baum wrote calling for the complete annihilation of remaining tribes. Another Baum biographer, Katharine M. Rogers (L. Frank Baum: Creator of Oz (2002) thought Baum’s editorial in the Pioneer (December 20, 1890)that recommended Native American extermination was “atypical,” spurred probably “by his depression at the time and the fears he shared with the other settlers in Dakota.”[i] At their core, these theories are testament to how the book has gripped our intellectual imagination as well.

Of course, most of us don’t need a theory to tell us what the story means. It’s something we feel, and have felt since our first trip to that land beyond the rainbow. There’s no place like home, it is true, but what has become clear is that there is also simply no place like Oz.