Notorious BIG Tells Us It Is All Right to Be about Nothing

A famous rapper is sued for being counter-revolutionary in his expropriation

January 19, 2024

I got questions about your life if you so ready to die …

—Trugoy the Dove (of De La Soul), “Long Island Degrees”

If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be a part of your revolution.

—Emma Goldman

Intent does not dictate impact. Artists know this frustrating fact better than anyone. Art is necessarily transactional. Especially popular art. It is made, and it is received. Indeed, it is made to be received. Delicate and precarious, this affective exchange, between artist and audience, between intent and impact, revolves around, and results in, one of the riskiest nouns: influence. A popular habit is to use the terms “influence” and “inspiration” interchangeably. This subtle but significant slip of terms signals a yearning for intent to dictate impact. The preference is to spotlight cases where the influenced party reflects, extends, and honors the sentiment of the influencer, and where the byproduct would make the original proud. We are inspired by such instances of inspiration. Yet sometimes influence manifests quite differently, and perhaps less inspiringly. Sometimes impact swallows intent whole and regurgitates it with a completely new meaning.

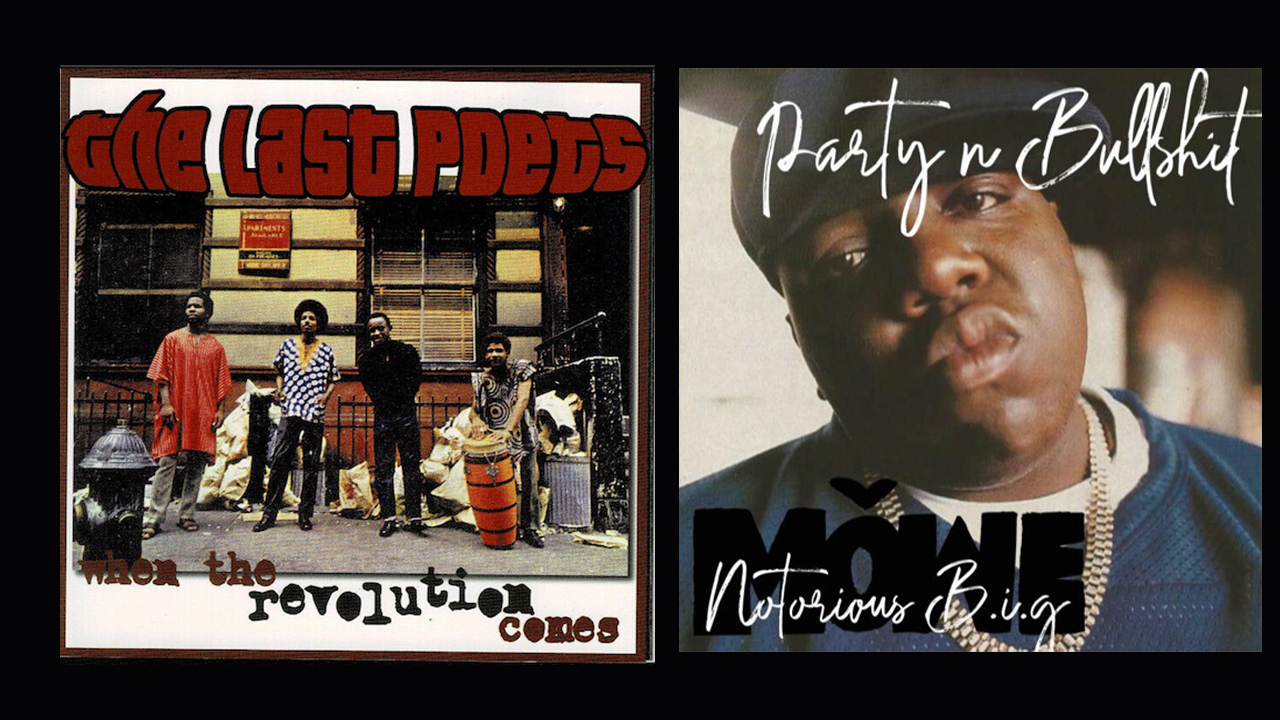

In March of 2016, Abiodun Oyewole, founding member of the path-breaking spoken-word group, The Last Poets, filed a copyright lawsuit against the estate of perhaps the greatest rapper of all time, the Notorious BIG (aka Biggie or BIG). A specific evocative expression connected the nationalist bard of the 1960s to the politically ambivalent emcee of the 1990s. An expression that, in its two usages, signaled both aesthetic continuity and an ideological impasse between two generations of African-American wordsmiths. Oyewole maintained that the chorus to BIG’s 1993 inaugural single, “Party and Bullshit,” had boosted the cadenced phrase, “party and bullshit,” from The Last Poets’ 1968 record, “When the Revolution Comes.” For this unauthorized adoption of the refrain, the poet sought $24 million in restitution. Yet, monetary compensation was not Oyewole’s motivating force.

We are inspired by such instances of inspiration. Yet sometimes influence manifests quite differently, and perhaps less inspiringly. Sometimes impact swallows intent whole and regurgitates it with a completely new meaning.

Since hip-hop’s turn from sub-culture to pop culture copyright lawsuits are hardly a rarity. Record sampling is a fundamental sonic and signifying dynamic of the genre, and conventional genre practices in hip-hop often translate into complex legal contestations. Sampled artists, often justifiably, feel entitled to a share of new capital generated by unlicensed or non-credited samples of their work. In short, the majority of sample-based lawsuits have been about money. However, this case was unique. It was not only all about money (although the $24 million at stake suggests it was at least somewhat about money). Oyewole argued that Biggie’s song had corrupted the message of the original and undermined its political objective. He maintained that the call for revolutionary action of the original had been replaced by a nihilistic embrace of sloth and indulgence in the adaptation. Oyewole’s case argued that the late Brooklyn-bred emcee had not merely profited from“When the Revolution Comes,” he had perverted it, and discouraged the prospect of revolution.

In 1968, the year that The Last Poets formed, revolution was a very real prospect. Only five years earlier, at the teetering peak of the civil rights movement, James Baldwin warned the nation that it must sincerely face its troubled racial past and unsteady present or suffer the reckoning of a Fire Next Time. By 1968, his language was revealed to be more than just a poetic forecast. It was literal. Vietnam draft cards and riotous cities alike were burning. The fire had come and, for many of the irreversibly disillusioned, the flames were keeping them warm. The Last Poets did not cause any of this, but they did soundtrack it. The group’s name, according to lore, was developed from the poem, “Towards A Walk in the Sun,” by Black Arts Movement poet Keorapeste Kgositsile, who suggested that soon poems would no longer be useful or necessary to the impending revolution. They, The Last Poets, would offer the final words before a wholesale turn to definitive action.

Despite their sincerity and the radical potential of the times, The Last Poets’ style of counter-culture militancy was widely embraced for, in the infamous parlance of Tom Wolfe, its “radical(ly) chic” commercial appeal. That is to say, while they spoke for the margins, The Last Poets were a relatively popular group. In 1970, their self-titled debut album, The Last Poets, peaked at No. 29 on the Billboard 200 and No. 3 on the R&B charts. Their critical and commercial success indicated that not only could Black be powerful and beautiful but, in the words of Craig Watkins, this radical Blackness was “bound to sell.”1 Like their contemporary spoken word pioneer, Gil Scott-Heron, The Last Poets were keenly aware of creeping commercial appropriations of Black Power. Both Scott- Heron and The Last Poets featured lyrics that spotlighted American materialism and vanity as national obsessions and prophesized that such decadence would bring national ruin. However, while Scott-Heron famously proclaimed that, “the revolution will not be televised,” The Last Poets were less sure.

The Last Poets features several provocative tracks about the hazardous balance of impending revolution and the fate of those unprepared for its dramatic inevitability. While a track like, “Niggers Are Scared of Revolution,” explores this theme at length, it is the concluding section of the song, “When the Revolution Comes,” that crystalized the group’s frustrated anxiety. In this song, co-founding member Omar Bin Hassen cannot shake the concern that, “some of us will probably catch it (the revolution) on TV.” He goes on to lament that until the revolution comes, “You know and I know that niggers will party and bullshit, and party and bullshit, and party and bullshit …” The lethargic melody of the repeated phrase conveys a hollow indulgence and a steady rhythm of unconsciousness maintained through complacency. Hassen cuts off the condemning chant and concludes with a despairing forecast that “…some might even die before the revolution comes.” The cause of these pre-revolution deaths is left ambiguous. Yet it is fair to conclude that death is a consequence of the ostensive self-destructive tendencies, or vulnerable circumstances, of the unenlightened non-revolutionary. They will die, the lyrics imply, at the hands of their inaction. The song, and the implications of the refrain “party and bullshit,” take on a complicated and ultimately tragic meaning twenty-three years later at the birth of Notorious BIG’s recording career.

Oyewole’s case argued that the late Brooklyn-bred emcee had not merely profited from“When the Revolution Comes,” he had perverted it, and discouraged the prospect of revolution.

No one has ever confused the Notorious BIG with a political revolutionary. A great rapper, yes, but not a political rapper. Debuting in 1992, Biggie’s emergence came with a complicated relationship to what is deemed hip-hop’s “golden era” of political rap (roughly 1988-1992.) While granted the seemingly capacious adjective, “political,” the likes of Jeffrey Decker and Charisse Cheney are right in stating that the politics of this era were almost unanimously nationalist. Thus, Cheney accurately terms this the “Golden Age of Black Nationalist rap.” Of course, Black Nationalism in the United States has a history as old as American history and, while its many variations echoed in the “Golden Age of Black Nationalist rap,” artists took their expressive and affective cues from the Black Power era of the 1960s and 1970s. Artists like Public Enemy and KRS-One, consistently alluded to Black Power iconography, rhetoric, and aesthetics to signal their political stance, contextualize contemporary social matters, and frame rap as a natural extension of previous modes of Black cultural radicalism. In this respect, The Last Poets are not a surprising source of inspiration among hip-hop artists of this era. When folks rightly state that The Last Poets are among the forefathers of hip-hop, the artists of this era are proof of their patriarchism. Rather, it is surprising that Biggie would draw on The Last Poets. Biggie commonly receives the loaded, albeit somewhat accurate, label of “gangster rapper.” In the shadow of the golden era of political rap Biggie was understood by some as dangerously apolitical. In the mid-90s, “conscious” artists like De La Soul and The Roots critiqued Biggie in this vein. While he certainly did not cause it, the era’s decline and Biggie’s rise were not unrelated. BIG’s career was born by broadcasting the end of the reign of Black Nationalist rap.

In 1992 the first ever “hip-hop whodunnit,” Who’s the Man? premiered in theatres to limited fanfare. My nostalgic love for the movie aside, the most important thing to come out of it was the soundtrack. More specifically, a single song from its soundtrack called, “Party and Bullshit.” This was the first song by budding mogul Puff Daddy’s newest artist, listed as simply, BIG. A hardcore record that doubled as a party anthem, the song was an underground sensation. And BIG, obese, wheezy, and lazy-eyed as he was, an unlikely and undeniable star. Like most magnetic people, Biggie’s appeal felt singular, as if he had access to something that was, for the rest of us, just beyond our grasp. As Fannie Kelley put it, his voice “sounds like it comes deeper in the chest than other people’s voices.”2 Even, or especially, in his most wanton expressions there was heart in Biggie’s heartlessness. From the very first line of the song; “I was terror/ since the public-school era…” his soon-to-be career hallmarks are all there; the mixture of wit and mayhem, the capacity to sinuously bend language into rhyme, and narrative clarity in the cloudiest of conditions. He performed “Party and Bullshit” to ecstatic club audiences in the buildup to his 1994 debut album, Ready to Die. Both in the song and in the crowd, everyone was having fun. It was a reckless sort of fun. Biggie rapped, “Where the party at? And can I bring my gat?” and everyone sang along with him in a collective desire for perilousness and pleasure. “Party and Bullshit” was BIG’s idea of celebration, the enlivening sensation of being dangerously close to the edge.

BIG closes the song’s first verse with the declaration and directive, “All we wanna do is…” with a chorus of men responding, “party and bullshit, and party and bullshit…” Variations on this call and response, which are only marginally more eager in tenor than The Last Poets’ chant in the original, function as the recurrent transition from verse to the hook throughout the song, as well as its volume-fading conclusion. Biggie’s alteration of the original lyrics is slight but significant. BIG shifts The Last Poets’ accusatory claim that non-revolutionary, “niggers will party and bullshit,” into a possessive pronoun of collective intention, i.e., “all we wanna do is party and bullshit.” Adopting the epithet, he embraces a state of condemnation. Whereas The Last Poets’ original phrasing signaled an accusation of lacking investment, Biggie expresses a celebratory desire for idleness. Through an aggressive act of intertextual signifying, BIG seized and usurped a status maligned by The Last Poets. In turn, he seductively offered it back to his listeners as a desirable state of carefree indulgence.

In the years that followed, the phrase became Biggie’s. The Last Poets were lost in a single degree of separation. The influence of “Party and Bullshit,” and specifically the repurposed meaning of the song’s pillaring phrase, was evident in its recurrent citation. Artists including Busta Rhymes, Rah Digga, Missy Elliot, Eminem, Lloyd Banks, and Rita Ora adapted or sampled the phrase in a manner that called to Biggie’s “Party and Bullshit” and not “When the Revolution Comes.” The distinction in homage can be gleaned by each song engaging in at least one of several facts: direct lyrical reference to BIG when using the phrase (“Got it All,” Eve), reproduction of the phrase’s slight but distinctive cadence (“Party and Bullshit” (Remix), (Rah Digga & “Get Light,” Nas), the inclusion of the terming within the context of celebratory subject matter (“Party and Bullshit,” Rita Ora), and/or direct sampling of the original song (“Party N Bullshit,” Lloyd Banks). Ultimately, it was the piling up of sonic evidence that set Oyweole’s lawsuit in motion.

The song, and the implications of the refrain “party and bullshit,” take on a complicated and ultimately tragic meaning twenty-three years later at the birth of Notorious BIG’s recording career.

In 2013, three years before the suit was brought, Oyweole stated that when “I wrote [about] ‘party and bullshit’ it was to make people get off their ass. But now ‘party and bullshit’ was used by Biggie…but not in a conscious way.” 3 In 2016, he doubled down on his disapproval and extended his concern to the growing number of songs that Biggie’s version had spawned, claiming that the phrase was being “polluted by the new uses that were glorifying, instead of cautioning against, a less serious approach to life.”4 The lawsuit was not only about Biggie’s song, it was about Biggie’s influence. Oyweole’s legal team argued that BIG’s original adaptation of the phrase “Party and Bullshit,” ushered in a series of subsequent adaptations that abandoned any reference to the political imperatives of “When the Revolution Comes.” This point is well taken. That is exactly what happened. As noted above, with each subsequent song the phrase was diluted of its original connotation to the point where it was a discernible gesture to BIG. In this respect, the phrase adaptation is undeniable. However, Oyewole’s charges regarding Biggie’s lack of “seriousness” and “conscious(ness)” are more complicated and, at core, false.

BIG was a fatefully serious artist. And the bulk of his material is dedicated to narrating the anguish of an expressly conflicted self-consciousness. His consciousness was certainly not the pointedly nationalist political consciousness of The Last Poets or their golden era disciples. Indeed, in their Marxian parlance, Biggie was a victim of “false consciousness.” Here, “consciousness” is more a colloquial reference than a literal description. It describes politics, not cognizance. It is a term that tells us a great deal about those who wield it, and less about who it describes. In fact, it threatens to obscure the person it describes. No, Biggie was not “conscious” in the sense of being a hopeful radical. Rather, he was a perceptive fatalist. Perhaps, Biggie was a “gangster rapper,” yet, as Orson Welles once described Macbeth, he presents, “a different kind of gangster, because he’s a gangster with a conscience.”5

So, what if someone selects false consciousness? Perhaps electing such a state of mind is more reprehensible than living it as an involuntary state. But it is a decision. A conscious decision. As such, maybe Biggie was amoral, but he was thoughtful. His amorality was a consequence of a disaffected logic. He did not merely lounge in this state of mind, he brought us to its most vulnerable and desperate corners. His work is saturated with a harrowing comprehension of the coerced limits of possibility knotted with a narcissistic tendency toward self-sabotage. The ever-looming promise of death was BIG’s primary subject. Indeed, his mortality provides the thematic binding for his masterpiece first album, Ready to Die.

For someone new to Notorious BIG’s music, it is hard to recommend songs from Ready to Die. Biggie’s first album, perhaps the most sustained exploration of depression in the history of music, is largely unpalatable, even unmanageable, for a novice. Certainly, Puff Daddy helped (in fact, he insisted) Biggie transcend his hardcore hip-hop ambitions with glossy singles “Juicy” and “One More Chance (remix).” These are the songs that got Biggie’s face or the Ready to Die album cover on T-Shirts available at Target and the Gap. However, these songs are glittery aberrations from the grim sonic and thematic arc of the album.

Fatalism bookends the album. From the first song, it is clear that our narrator is prepared, and is preparing us, for the inevitable conclusion. On “Things Done Changed” Biggie drifts between lament, ambivalence, and acceptance as he details the material and psychological landscape of displaced young men like himself; specifically, the brevity of their adolescence and the pull of criminality.

Even in death, Biggie elected for party and bullshit. Kevin Young declared that BIG “returned the blues mood to hip-hop.”6 BIG’s preoccupation with living life always ready to die is part of a blues tradition in which the potentially dulling omnipresence of sorrow is lined with the expressive efforts to, in the words of Ralph Ellison, “squeeze a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism” from the pain. Indeed, Young is right, as was Ellison. If, as Ellison famously put it, as “a form, the blues is an autobiographical chronicle of personal catastrophe expressed lyrically,” then Biggie was a bluesman through and through.7

Judge Nathan cited that Oyewole’s impetus for the case was an admission that the song had been altered. Ironically, it was the accuracy of Oyewole’s interpretation of “Party and Bullshit,” the entire premise of his case, that caused his loss. Biggie had not used The Last Poets’ phrase; he had reimagined the phrase.

The Notorious BIG was murdered March 9, 1997. Two weeks later his highly anticipated sophomore double album, Life After Death, was released. The album’s title is hauntingly literal. The cover features Biggie standing by a hearse. The liner notes are accompanied by pictures of Biggie clad in all-black standing in a graveyard, staring knowingly at the camera. These are ominous and chilling images. There is no malice, nor any pleading, in his facial expression. It looks like he knew. It looks like he knows.

On March 8th, 2018, on the dawn of the twenty-first anniversary of BIG’s death, U.S. New York District Judge Alison J. Nathan dismissed Oyewole’s case. The decision was grounded in the conclusion that BIG had transformed the meaning of The Last Poets’ lyrics. In her explanation, Judge Nathan cited that Oyewole’s impetus for the case was an admission that the song had been altered. Ironically, it was the accuracy of Oyewole’s interpretation of “Party and Bullshit,” the entire premise of his case, that caused his loss. Biggie had not used The Last Poets’ phrase; he had reimagined the phrase. Subsequently, the influence of Biggie on artists like Busta Rhymes and Lloyd Banks was proof of The Last Poets’ displacement from the primary seat of influence. Yet, influence is not a zero-sum game. The Last Poets continue to influence hip-hop. They were not the last of their kind. They have collaborated with the likes of Common and Kanye West, been sampled by Killer Mike, and noted their approval of artists like Kendrick Lamar and J Cole. Each of these artists have also cited Biggie as an influence. Perhaps The Last Poets’ revolutionary call and Biggie’s pessimistic indulgence are odd bedfellows. But they both resonate. Influence does not demand consistency. Many would like revolution to come with a bit of room to party and bullshit, too.

1Craig Watkins, “Black is Back, and It’s Bound to Sell! Nationalist Desire and the Production of Black Popular Culture,” Is It Nation Time: Contemporary Essays on Black Power and Black Nationalism, eds, Eddie S. Glaude (University of Chicago, 2002).

2 Fannie Kelley, “Biggie Smalls: The Voice of a Generation,” NPR STL Public Radio, August 2, 2010. https://www.npr.org/2010/08/02/128916682/biggie-smalls-the-voice-that-influenced-a-generation

3 Oyewole, Abiodun. Interview by SameOldShawn, “Outside the Lines with Rap Genius,” October 9, 2012.https://genius.com/Outside-the-lines-with-rap-genius-new-podcast-umar-bin-hassan-of-the-last-poets-51-annotated

4 “Notorious B.I.G. Estate Evades Copyright Lawsuit,” JDSUPRA, March 19, 2018. https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/notorious-b-i-g-estate-evades-copyright-58552/

5 Orson Welles, “Monologue from Macbeth,” The Steve Allen Plymouth Show, NBC, April 6, 1958.

6 Kevin Young, Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness (Graywolf Press, 2012), 384.

7 Ralph Ellison, “Richard Wright’s Blue,” Living with The Music: Ralph Ellison’s Jazz Writings, edited Robert O’Meally (Modern Library Classics, 2001), 103.