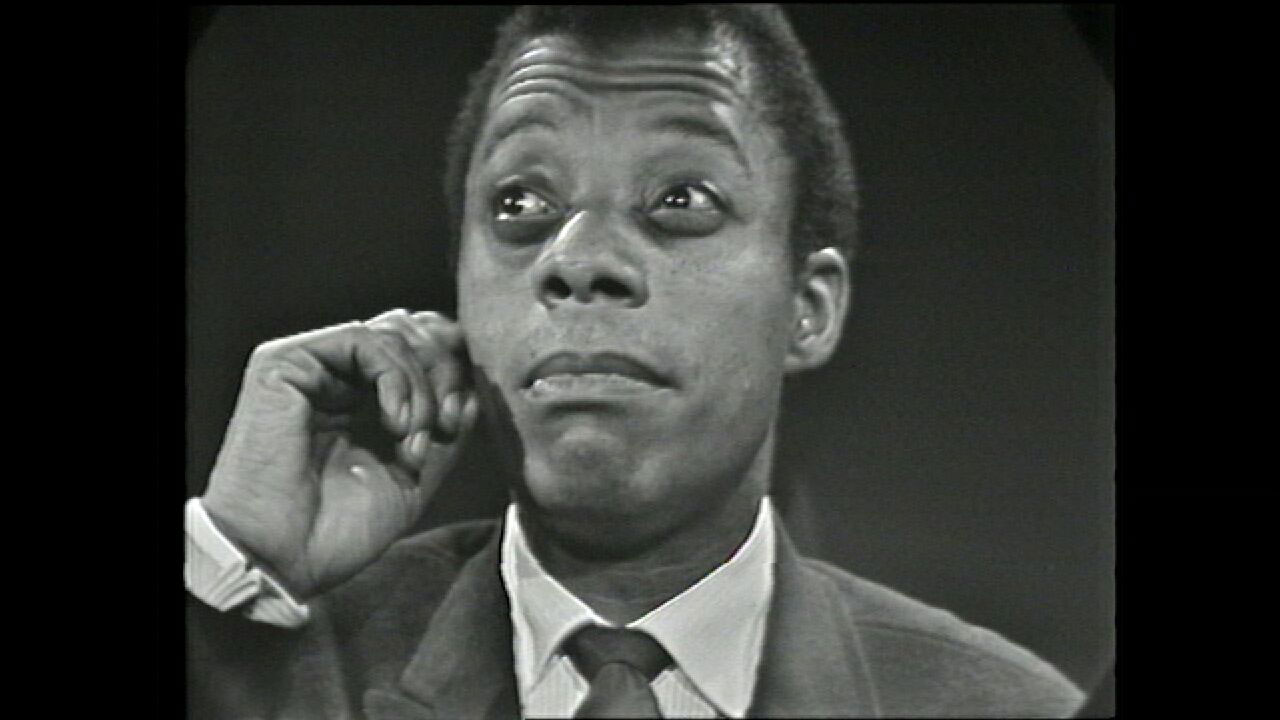

When I was in my third year of fulltime college teaching, I assigned James Baldwin’s essays for the first time. I had read Baldwin in college myself—the Baldwin a lot of people read in college, The Fire Next Time and a few other short pieces—and I thought he would provide an excellent conclusion to a course I was teaching on the literature of the long civil rights movement. Most of the students were history majors, and I anticipated with interest their reaction to expository prose highly polished into art.

But then I reread Baldwin—this time diving into his essays in an immersive rush—and I was mortified that I had only vaguely understood just how transformative his work was. It makes me feel slightly better to note Ta-Nehisi Coates’s observation that his own college reading of Baldwin left him only “basically … with the sense that he was a badass,” and that his appreciation of Baldwin only burgeoned when he returned to him years later.¹

I asked the students to buy the Library of America edition of Baldwin’s essays and assigned more famous pieces like The Fire Next Time and No Name in the Street, Baldwin’s wrenching account of the civil rights movement, punctuated by the woundings and killings of his friends and loved ones. But I also included some of Baldwin’s later work, like his musings on the meanings of American history and on his own identity as a black gay man.

Preparing the students to read, I said something like this: “We’re talking about Baldwin next week, so make sure you’re ready. This’ll change your life. I tell you that sometimes about the stuff you read, and usually I’m exaggerating, but this time I’m really not.” At our next meeting, in that sometimes awkward interregnum—the last three minutes before class starts, as we wait for that one last person—one of the girls sitting in the back caught my eye and said, “You were right. I think this changed my life.” And over the next week or so, more than one student who had first gotten the book from the library mentioned buying it.

Preparing the students to read, I said something like this: “We’re talking about Baldwin next week, so make sure you’re ready. This’ll change your life. I tell you that sometimes about the stuff you read, and usually I’m exaggerating, but this time I’m really not.”

Why did my class find Baldwin so compelling? Yes, he can suddenly seem to be in your head, taking a vague notion out of the sludge of your subconscious and articulating it with crystalline clarity. Or he can abruptly show you something you have never considered before and force you to wonder painfully at your own naivety. Talking to other teachers, I find that I think there was more to it. How students respond to Baldwin may reflect the conflicts of their own lives as young people in universities. American universities have never quite escaped the legacies of the 1960s. No matter where the tide of student protest flows at a given moment, the default rhetorical mode for discussion of young people’s exploits is comparison. Many adults bemoan the grim careerism of today’s students or respond impatiently to complaints about so-called microaggressions or calls for safe spaces. Students now have no social conscience, they are told, or their concerns are petty or solipsistic, only poor imitations of the bold protests of fifty years ago. Students know and often resent these comparisons. As a result, they sometimes can see Baldwin only in the context of a time period they have been taught to mythologize. One of the teachers I respect most, reflecting on assigning The Fire Next Time, reported that some students, even with the best intentions, just cannot get their heads around a time they see as fundamentally different from their own.

Baldwin’s voice loses its resonance for them, because they simply do not speak the language of his era. Other professors, pondering their own Baldwin teaching experiences, describe their students as resentful of what they perceive as Baldwin’s idealism, what they see as his gratingly naïve sense of American civic faith betrayed. They insist he has nothing to say to them, who have been nurtured on the idea that there is no such faith to keep.²

This is not only distance. It is antipathy. Thinking about it, I suppose some students, aghast at or sick of the injustices they see around them, look with a jaundiced eye at Baldwin’s assurances that such things have happened before. His point is to let us know we are not alone, to make sure that outraged and injured voices do not have to be isolated. It is a writer’s attempt to comfort his readers with a realization that has been born of his own pain. But perhaps many young people feel that assurance smacks too much of the dismissals they are used to from the adults around them. All the things you’re angry about people have been angry about before, and, if they have not, it is because what you are angry about is not worth it. Understandably, they do not want the acuity of their pain and indignation devalued in the sharing.

But there are places where Baldwin meets the twenty-first century seamlessly. In the weeks I taught his work, my students seemed to feel pleased recognition, not resentment. Rather than speaking of an alien past, they heard him talking to them about their own world. The fundamental callousness with which America still treats the poor and readily assumes them to be criminal, the fear of young people who do not know if families will accept a child’s sexual or gender identity—these are issues that remain immediate. Baldwin’s tenderness for the fearful and the mistreated struck chords in my students. But they also read in his prose glimpses of a world that Baldwin hoped for and that people their age have begun to grow up in. Baldwin’s basic demand, after all, the demand that animated all his work, was that his fellow citizens accept individuals on their own terms, in all the complexity and contradiction that made them unique. The world had looked at him and first tried to abuse and silence him because he was black and gay and then assumed (with all the force at its command behind the assumption) that he would behave in ways predetermined by those characteristics. He looked forward to a better time. When the world could look at James Baldwin and see him as a gay black man and also a man who smoked a lot of cigarettes and had ambivalent feelings about blues and did not want to learn to drive and worried constantly about the children he knew and rather liked knowing famous people, we would have reached a more humane world. My students were born in the first generation that will pass its adult life in an America where gay marriage is the law of the land. They were unborn or still children when the U.S. Census began allowing for the identification of mixed-race identity. And they may value tremendously friends they never see, because they share their mutual giggles and confidences through screens. They can understand Baldwin’s demand. They are living in a world that may yet meet that demand, and some of them know how fiercely they must guard that possibility. The world has finally caught up with him, so he is speaking directly to them, in their native language.

Other professors, pondering their own Baldwin teaching experiences, describe their students as resentful of what they perceive as Baldwin’s idealism, what they see as his gratingly naïve sense of American civic faith betrayed.

These were insights I had, in a preliminary way, as I taught Baldwin that spring and watched students submerge themselves in his sentences. When I went on job interviews and had to talk about particularly stimulating and enjoyable teaching experiences, I cheerfully recounted those weeks and my thoughts about them. But as the years go on, as courses evolve and new crops of students sit in front of me, I have come to realize that when I speak about teaching Baldwin, I am in a sense talking about all my teaching. My own most influential undergraduate teacher, thinking on some of these issues recently, articulated what I had vaguely felt, when he noted that Baldwin requires of you as a teacher that you have all the energy and vibrancy that he does. After years of struggling to write buzzword-laden teaching philosophies that bear little relationship to what actually happens in my classroom, I have begun to realize that Baldwin articulated as close to a philosophy as I really practice.

Baldwin, when he did speak to teachers, insisted that he was glad he was not one, that it was too great a responsibility. But he had himself been a student and an adult who had cared about vulnerable young people. He remembered his own high school teachers and how crucial they had been to his development. And long before he had picked up teaching appointments as a visiting writer at a series of universities, he had modeled that memory into his own moral imperative. Again and again, he returned to, “all the ruined children that I have watched all my life being destroyed … as we sit here, and being destroyed in silence.” Destruction could take many forms—from jobless, drug-addicted despair to ignorant and smug obtuseness. But it was not children’s fault they were destroyed. Instead, it was the fault of adults who had inured themselves to injustices ossified into inevitabilities, who had failed to protect the young from them or pass on the capacity to confront them. Looking down at the corpse of a 27-year-old heroin addict in a Harlem funeral parlor, Baldwin summed up his philosophy for work and life with all the searing tenderness he could conjure. “Anyway, that dead boy is my subject and my responsibility. And yours.”³ As Baldwin has charged me, I know that my students may need me to be there for them as they navigate both the sometimes predictable currents of growing up and the truly devastating squalls that threaten to sweep away their ability to go forward, the crises that would challenge anyone, no matter how allegedly adult. That is my job, as much as anything—to listen and to care and to try to help or at least to do no harm, no more than what the world has done and continues to do.

Caring is, of course, no task for the faint of heart, nor is it about taking pride in how much students seem to like you. (I shudder to think what Baldwin would have to say about that.) It involves, first of all, a recognition that the student you see in the classroom is a tiny fraction of what that person is at this period of his or her life. Students may choose to share parts of their happiness with you, and they may even choose to show you some of their pain. But none of us ever shows all our pain to anyone, not least because we do not always know how much of it we carry, since it seems merely the necessary cost of living. I think sometimes of the teacher Baldwin mentions briefly in Notes of a Native Son, the young and earnest white woman who took him to plays and helped his family when Baldwin’s father lost his job. She was clearly a good woman, as Baldwin and his mother both understood. But Baldwin the essayist does not keep us in the theater with her. He focuses his story in the confines of the family’s Harlem apartment, where his father rages with fear and frustration at the woman’s presence in his son’s life, where the son makes an instant and cold calculation of race and privilege and self-interest in order to seize his chance at playgoing. No matter how well-intentioned, the teacher remains a tangential figure to the webs of friendship, obligation, and memory that extend from every student. All children’s education, as Baldwin points out, begins long before school. By the time you teach a child of any age, you are only contributing to a long set of lessons already learned, rubbing up against a padding of scar tissue long accreted. The job is to be present as the students stretch that scar tissue and try to ensure that it does not limit the range of motion in their limbs, mental and emotional.

Baldwin, when he did speak to teachers, insisted that he was glad he was not one, that it was too great a responsibility. But he had himself been a student and an adult who had cared about vulnerable young people. He remembered his own high school teachers and how crucial they had been to his development.

The job is also, of course, to be there when students experience some new pain. When Baldwin interviewed the young people who led the waves of students into newly desegregated schools, he found himself immediately confronted with walls of polite silence. “I began to realize,” he says early on in “A Fly in Buttermilk,” “that there were not only a great many things G. would not tell me, there was much that he would never tell his mother.”⁴ These are people old enough to make the decision that some traumas can and must be solely personal. They are too much to tell. Some of those come from encounters with big injustices, but most of them are just from the process we disguise under the benign phrase “growing up.” Baldwin himself keeps poking at those growing-up scars he carries with him—the sorrows over the friends he lost because of his own limitations or their own, the hopes flash-frozen, and all the other experiences that bring one up, years later, with a jerk. Some days as I look at the faces in front of me, I know that all I can do is to be there while all this happens to people around me. Presence, sometimes, is all there can be. As I tell my graduate students when we talk about teaching, “Students need you to be the grownup in the room.” And what I mean is that they need someone self-aware and strong enough not to try to dominate them but to hold the boundaries around them, to make a place where they can unfurl their fledgling certainties, test out the cornerstones of who they are and will be.

But Baldwin demands more than caring. Recounting one of his own teaching experiences, as a visiting writer at Bowling Green State University, he remembered his shock when, at the beginning of class on the first day, a student immediately asked why white people hated black people. Like any teacher speaking on an ongoing and controversial debate, Baldwin admitted that he had planned to work up to that question, to feel out the class and talk his way around to it. But his students had no patience for that. “I underestimated the children, and I am afraid that most of the middle-aged do,” he concluded.⁵ And that is his second and harder demand of those who would teach. Do not underestimate the children. They may well be braver and better than you are, so you must be ready for them. Youth is no reliable measure of a person’s worthiness of respect or capacity for critical thought.

So teaching means staying prepared to engage their questions and to recognize the power of the world to crush the flexibility and independence of thought that many so-called adults seem to find jejune. Most teachers of high-school and college-age folks have heard a student say, “Well, I really want to do this next, but my mom and dad say I should just….” The answer is never, in my experience, more unusual than the alternative the student has come up with. And it usually reflects the clinging power of the predictable and its equation with safety. These conversations are sometimes painful, because you can see a student consciously letting go of something in exchange for parental approval—or at least the absence of active parental anxiety or opposition. It is, perhaps, a gesture of love, but it is also sometimes a compromise made in an effort to be worthy of love—to be a good son or daughter, a responsible adult. Equally painful and increasingly common in my office are the conversations with students caught in the vice of loan debt, their choices dictated by the imperatives of repayment. These are waters that are often too deep for a swimmer who does not know them. So, on the other side of the office desk, all I can do is remind my visitor gently that his or her complicated and imperfect and individual self is worthy of respect.

When Baldwin interviewed the young people who led the waves of students into newly desegregated schools, he found himself immediately confronted with walls of polite silence.

In describing his conversations with young people in San Francisco in No Name in the Street, Baldwin models the kind of gentleness necessary for these conversations and so many others—the ones with students who have only now encountered a new and fascinating idea or a new and unbearable injustice. The questions he remembers, from both white and black kids alike, are earnest, confused, worried, sometimes cringeworthy. But his patience, as he renders it on the page, is infinite. “Real questions can be absurdly phrased,” he concedes, “and probably can be answered only by the questioner, and, at that, only in time. But real questions, especially from the young, are very moving, and I will always remember the faces of some of those children. Though the questions facing them were difficult, they appeared for the most part, to like the challenge.”⁶ That spirit is to be cherished, not dismissed.

The best of my teachers used to say casually, “I’ve never taught anybody anything. I’ve just been around when people learned things.” I used to think that was an elegant formulation rarified above anything I could aspire to. But the longer I teach the more I think it is true for me as well. There are more and more people I have been privileged to have in my classroom that I would feel ridiculous saying I had taught anything. I gave them the opportunity to learn and somebody to care whether they did or not and to help them hone the skills with which they encountered and processed the information the world had to offer them.

And I tried to suggest to them just how much the world has to offer—not only in the way of information, but in the way of questions. I want to do what Baldwin remembered his friend, the painter Beauford Delaney, doing for him: showing him with his own seeing just how much there was to see.⁷ You do not have to teach something brand new to do that. When I teach the Gettysburg Address, I am also asking my students to question what it meant to re-dedicate a nation on the basis of a rebirth of freedom. What, after all, does it mean to be free? These are questions that far transcend the test coming up in three weeks. Baldwin suggests how important it is that we always teach on multiple levels, offering the example: “one has not learned anything about Castro when one says, ‘He is a Communist.’ This is a way of not learning something about Castro, about Cuba, something, in fact, about the world.”⁸ Pairing a name and a date or a country and a law or any of the infinite sets of facts that historians shovel through, is not in itself illuminating. It is the very barest of beginnings, particularly if the pairing can be used to somehow fool the learner into thinking he or she knows everything necessary. Because if you know everything you do not ask. You do not ask the most important questions: why do people believe the things they do? What about their beliefs has made the world around you better and what worse? What does it really mean to be free? Are you free? Who are you, anyway? If my students learn to ask those kinds of questions, then I was around when they learned the most important thing.

I want to do what Baldwin remembered his friend, the painter Beauford Delaney, doing for him: showing him with his own seeing just how much there was to see. You do not have to teach something brand new to do that.

There are dangers, of course, for a student who becomes educated. “The purpose of education, finally,” Baldwin opined, “is to create in a person the ability to look at the world for himself, to make his own decisions, to say to himself this is black or this is white, to decide for himself whether there is a God in heaven or not. To ask questions of the universe, and then learn to live with those questions, is the way he achieves his own identity. But no society is really anxious to have that kind of person around.” Which is to say that teachers may be the only or the best allies students have in the decision to become educated. And that is a great and honorable responsibility.