Editor’s Preface: Bat Masterson’s career as a writer was nearly as substantial as his career as a gunfighter. He spent the last 21 years of life writing a thrice-weekly column for a New York newspaper. Most of the pieces were about prize-fighting, but Masterson also wrote about contemporary politics and the glory days of the Old West, the latter of which he was certainly expert, as he was there. Masterson was not a trained journalist, and his writing is frequently ill-tempered, biased and inflated. Masterson also loved to use big words because he thought they had a particular dramatic impact. It must be said, to his credit, that he used these words correctly, most of the time. This piece is one of the most famous, and influential, about Wyatt Earp, especially because Masterson knew Earp personally, and had worked with him as a law enforcement officer in Dodge City. To learn more about Masterson’s career as a writer we refer you to Gerald Early’s review of Gunfighter in Gotham: Bat Masterson’s New York City Years.

Thirty-five years ago that immense stretch of territory extending from the Missouri River west to the Pacific Ocean, and from the Brazos River in Texas north to the Red Cloud Agency in Dakota, knew no braver or more desperate man than Wyatt Earp, the subject of this narrative. Wyatt Earp is one of the few men I personally knew in the West in the early days, whom I regarded as absolutely destitute of physical fear. I have often remarked, and I am not alone in my conclusions, that what goes for courage in a man is generally the fear of what others will think of him—in other words, personal bravery is largely made up of self-respect, egotism, and an apprehension of the opinion of others.

Wyatt Earp’s daring and apparent recklessness in time of danger is wholly characteristic; personal fear doesn’t enter into the equation, and when everything is said and done, I believe he values his own opinion of himself more than that of others, and it is his own good report that he seeks to preserve. I may here cite an incident in his career that seems to me will go far toward establishing the correctness of the estimate I have made of him.

Claimed the Cards Were Crooked

He was once engaged in running a faro game in Gunnison, Colorado, in the early days of that camp; and one day while away from the gambling house, another gambler, by the name of Ike Morris, who had something of a local reputation as a bad man with a gun, and who was also running a faro game in another house in the camp went into Wyatt’s game and put down a roll of bills on one of the cards and told the dealer to turn. The dealer did as he was told, and after making a turn or two, won the best and reached out on the layout and picked up the roll of bills and deposited them in the money-drawer. Morris instantly made a kick and claimed tha the cards were crooked, and demanded the return of his money. The dealer said that he could not give back the money, as he was only working for wages, but advised him to wait until Mr. Earp returned, and then explain matters to him, and as he was the proprietor of the game he would perhaps straighten the matter up. In a little while Wyatt returned, and Morris was on hand to tell him about the squabble with the dealer, and incidentally ask for the return of the money he had bet and lost. Wyatt told him to wait a minute and he would speak to the dealer about it; it things were as he represented he would see what could be done about it. Wyatt stepped over to the dealer and asked him about the trouble with Morris. The dealer explained the matter, and assured Wyatt that there was nothing wrong with the cards, and that Morris had lost his money fairly and squarely. By the time the house was pretty well filled up, as it got noised about that Morris and Earp were likely to have trouble. A crowd had gathered in anticipation of seeing a little fun. Wyatt went over to where Morris was standing and stated that the dealer had admitted cheating him out of his money, and that he felt very much like returning it on that account; but said Wyatt—“You are looked upon in this part of the country as a bad man, and if I was to give you back your money you would say as soon as I left town, that you made me do it, and for that reason I will keep the money.” Morris said no more about the matter, and after inviting Wyatt to have a cigar, returned to his own house, and in a day or two left the camp.

Lost His Reputation In The Camp

There was really no reason why he should have gone away, for so far as Wyatt was concerned the incident was closed; but he perhaps felt that he had lost whatever prestige his reputation as a bad man had given him in the camp, and concluded it would be best for him to move out before some other person of lesser note than Wyatt Earp took a fall out of him. This he knew would be almost sure to happen if he remained. He did not need to be told that if he remained in town after the Earp incident got noised about, every Tom, Dick and Harry in camp would be anxious to take a kick at him, and that was perhaps the reason for his sudden departure for other fields where the fact of his punctured reputation was not so generally known.

… he was not one of those human tigers who delighted in shedding blood just for the fun of the thing. He never, at any time in his career, resorted to the pistol excepting in cases where such a course was absolutely necessary.

The course pursued by Earp on this occasion was undoubtedly the proper one—in fact the only one—able to preserve his reputation and self-respect. It would not have been necessary for him to have killed Morris in order to have sustained his reputation, and very likely that was the very last thing he had in mind at the time, for he was not one of those human tigers who delighted in shedding blood just for the fun of the thing. He never, at any time in his career, resorted to the pistol excepting in cases where such a course was absolutely necessary. Wyatt could scrap with his fists, and had often taken all the fight out of bad men, as they were called, with no other weapons than those provided by Nature.

There were few men in the West who could whip Earp in a rough-and tumble fight 30 years ago, and I suspect that he could give a tough youngster a hard tussle right now, even if he is 61 years of age.

In all probability had Morris been known as a peaceable citizen, he would have had his money returned when he asked for it, as Wyatt never cared much for money; but being known as a man with a reputation as a gunfighter, his only chance to get his money back lay in his ability to “do” Earp, and that was a job he did not care to tackle.

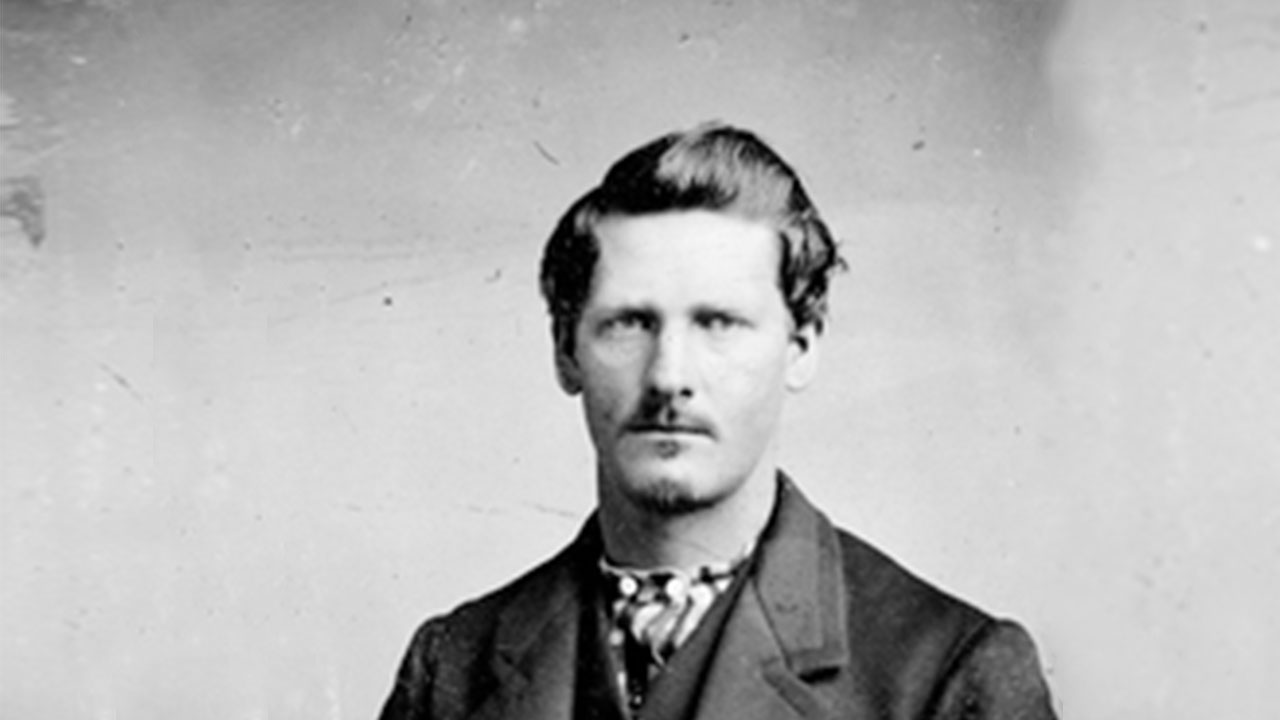

I have known Wyatt Earp since early in the ’70s, and have seen him tried out under circumstances that made the test of manhood supreme. He landed in Wichita, Kansas, in 1872, being then about 26 years old, and weighing in the neighborhood of 160 pounds, all of it muscle. He stood 6 feet in height, with light blue eyes, and a complexion bordering on the blonde. He was born at Monmouth, Illinois, of a clean strain of American breeding, and served in an Iowa regiment the last three years of the Civil War, although he was only a boy at the time. He always arrayed himself on the side of law and order, and on a great many occasions, at the risk of his life, rendered valuable service in upholding the majesty of the law in those communities in which he lived. In the spring of 1876 he was appointed Assistant City Marshal of Dodge City, Kansas, which was then the largest shipping point in the North for the immense herds of Texas cattle that were annually driven from Texas to the northern markets. Wyatt’s reputation for courage and coolness was well known to many of the citizens of Dodge City—in fact it was his reputation that secured for him the appointment of Assistant City Marshal.

He was not very long on the force before one of the alderman of the city, presuming somewhat on the authority his position gave him over a police officer, ordered Wyatt one night to perform some official act that did not look exactly right to him, and Wyatt refused point blank to obey the order. The alderman, regarded as something of a scrapper himself, walked up to Wyatt and attempted to tear his official shield from his vest front where it was pinned. When that alderman woke up he was a greatly changed man. Wyatt knocked him down as soon as he laid his hands on him, and then reached down and picked him up with one hand and slammed a few hooks and upper-cuts into his face, dragged his limp form over to the city calaboose, and chucked it in one of the cells, just the same as he would any other disturber of the peace. The alderman’s friends tried to get him out on bail during the night, but Wyatt gave it out that it was the calaboose for the alderman until the police court opened up for business at nine o’clock the following morning, and it was. Wyatt was never bothered any more while he lived in Dodge City by aldermen.

The alderman, regarded as something of a scrapper himself, walked up to Wyatt and attempted to tear his official shield from his vest front where it was pinned. When that alderman woke up he was a greatly changed man.

While he invariably went armed, he seldom had occasion to do any shooting in Dodge City, and only once do I now recall when he shot to kill, and that was at a drunken cowboy, who rode up to a Variety Theatre where Eddie Foy, the now famous comedian, was playing an engagement. The cowboy rode right by Wyatt, who was standing outside the main entrance to the show shop, but evidently he did not notice him else he would not in all probability have acted as he did.

An Incident Not On The Program

The building in which the show was being given was one of those pine-board affairs that were in general use in frontier towns. A bullet fired from a Colts 45 caliber pistol would go through a half-dozen such buildings, and this the cowboy knew. Whether it was Foy’s act that angered him, or whether he had been jilted by one of the chorus we never learned; at any rate he commenced bombarding the side of the building directly opposite the stage upon which Eddy Foy was at that very moment reciting that beautifully pathetic poem entitled “Kalamazoo in Michigan.” The bullets tore through the side of the building scattering pieces of the splintered pine-boards in all directions. Foy evidently thought the cowboy was after him, for he did not tarry long in the line of fire.

The cowboy succeeded in firing three shots before Wyatt got his pistol in action. Wyatt missed at the first shot, which was probably due to the fact that the horse the cowboy was riding kept continually plunging around, which made it rather a hard matter to get a bead on him. His second shot, however, did the work, and the cowboy rolled off his horse and was dead by the time the crowd reached him.

Wyatt’s career in and around Tombstone, Arizona, in the early days of that bustling mining camp was perhaps the most thrilling and exciting of any he ever experienced in the 35 years he has lived on the lurid edge of civilization. He had four brothers besides himself who waggoned it into Tombstone as soon as it had been announced that gold had been discovered in the camp.

Wyatt’s career in and around Tombstone, Arizona, in the early days of that bustling mining camp was perhaps the most thrilling and exciting of any he ever experienced in the 35 years he has lived on the lurid edge of civilization.

Jim was the oldest of the brothers. Virgil came next, then Wyatt, then Morgan, and Warren, who was the kid of the family. Jim started in running a saloon as soon as one was built. Virgil was holding the position of U.S. Deputy Marshal. Wyatt operated a gambling house, and Morgan rode as a Wells Fargo shot-gun messenger on the coach that ran between Tombstone and Benson, which was the nearest railroad point. Morgan’s duty was to protect the Wells Fargo coach from the stage robbers with which the country at that time was infested.

Stage Robbers of San Simon Valley

The Earps and the stage robbers knew each other personally, and it was on this account that Morgan had been selected to guard the treasure the coach carried. The Wells Fargo Company believed that so long as it kept one of the Earp boys on the coach their property was safe; and it was, for no coach was ever held up in that country upon which one of the Earp boys rode as guard.

A certain band of those stage robbers who lived in the San Simon Valley, about 50 miles from Tombstone and very near the line of Old Mexico, where they invariably took refuge when hard pressed by the authorities on the American side of the line, was made up of the Clanton brothers, Ike and Billy, and the McLaury brothers, Tom and Frank. This was truly a quartette of desperate men, against whom the civil authorities of that section of the country at that time were powerless to act. Indeed, the United States troops from the surrounding posts, who had been sent out to capture them dead or alive, had on more than one occasion returned to their posts after having met with both failure and disaster at the hands of the desperadoes.

Those were the men who made up their minds to hold up and rob the Tombstone coach; but in order to do so with as little friction as possible, they must first get rid of Morgan Earp. They could, as a matter of course, ambush him and shoot him dead from the coach; but that course would hardly do, as it would be sure to bring on a fight with the other members of the Earp family and their friends, of whom they had a great many. They finally concluded to try diplomacy. They sent word to Morgan to leave the employ of the Wells Fargo Express Company, as they intended to hold up the stage upon which he acted as guard, but didn’t want to do it as long as the coach was in his charge.

Morgan sent back word that he would not quit and that they had better not try to hold him up or there would be trouble. They then sent word to Wyatt to have him induce Morgan, if such a thing was possible, to quit his job, as they had fully determined on holding up the coach and killing Morgan if it became necessary in order to carry out their purpose.

Wyatt sent them back word that if Morgan was determined to continue riding as guard for Wells Fargo he would not interfere with him in any way, and that if they killed him he would hunt them down and kill the last one in the bunch. Just to show the desperate character of those men, they sent Virgil Earp, who was City Marshal of Tombstone at the time, word that on a certain day they would be in town prepared to give him and his brothers a battle to the death.

Sure enough, on the day named Ike and Billy Clanton and Tom and Frank McLaury rode into Tombstone and put their horses up in one of the city corrals. They were in town some little time before the Earps knew it. They never suspected for a moment that the Clantons and McLaurys had any intention of carrying out their threat when they made it. When Virgil Earp fully realized that they were in town he got very busy. He knew that it meant a fight and was not long in hustling up Wyatt and Morgan and “Doc” Holliday, the latter as desperate a man in a tight place as the West ever knew. This made the Marshal’s party consist of the Marshal himself, his brothers Wyatt and Morgan, and “Doc” Holliday. Against them were the two Clantons and the two McLaurys, an even thing so far as numbers were concerned. As soon as Virgil Earp got his party together, he started for the corral, where he understood the enemy was entrenched, prepared to resist to the death the anticipated attack of the Earp forces.

The Town Turned Out For the Battle

Everybody in Tombstone seemed to realize that a bloody battle was about to be fought right in the very center of the town, and all those who could, hastened to find points of vantage from which the impending battle could be viewed in safety. It took the City Marshal some little time to get his men together, as both Wyatt and Holliday were still sound asleep in bed, and getting word to them and the time it took for them to get up and dress themselves and get to the place where Verge and Morgan were in waiting, necessarily caused some little delay. The invaders, who had been momentarily expecting an attack, could not understand the cause of this delay, and finally concluded that the Earps were afraid and did not intend to attack them, at any rate while they were in the corral. This conclusion caused them to change their plan of battle.

They instantly resolved that if “The mountain would not come to Mahomet, Mahomet would go to the mountain.” If the Earps would not come to the corral, they would go and hunt up the Earps. Their horses were nearby, saddled, bitted and ready for instant use. Each man took his horse by the bridle-line and led him through the corral-gate to the street where they intended to mount.

But, just as they reached the street, and before they had time to mount their horses, the Earp party came round the corner. Both sides were now within 10 feet of each other. There were four men on a side, every one of whom had during his career been engaged in other shooting scrapes and were regarded as being the most desperate of desperate men. The horses gave the rustlers quite an advantage in the position. The Earps were in the open street, while the invaders used their horses for breast-works. Virgil Earp, as the City Marshal, ordered the Clantons and McLaurys to throw up their hands and surrender.

They instantly resolved that if “The mountain would not come to Mahomet, Mahomet would go to the mountain.” If the Earps would not come to the corral, they would go and hunt up the Earps.

This order they replied to with a volley from their pistols. The fight was now on. The Earps pressed in close, shooting as rapidly as they could. The fight was hardly started before it was over, and the result showed that nearly every shot fired by the Earp party went straight home to the mark.

Further Developments of the Feud

As soon as the smoke of battle cleared away sufficiently to permit of an accounting being made, it was seen that the two McLaurys and Billy Clanton were killed. They had been hit by no less than a half dozen bullets each and died in their tracks. Morgan Earp was the only one of the Marshal’s force that got hit. It was nothing more; however, than a slight flesh wound in one of his arms. Ike Clanton made his escape, but in doing so stamped himself as a coward of the first magnitude. No sooner had the shooting commenced than he threw down his pistol and with both hands high above his head; he ran to Wyatt Earp and begged him not to kill him. Here again, Wyatt showed the kind of stuff that was in him, for instead of killing Clanton as most any other man would have done under the circumstances, he told him to run and get away, and he did.

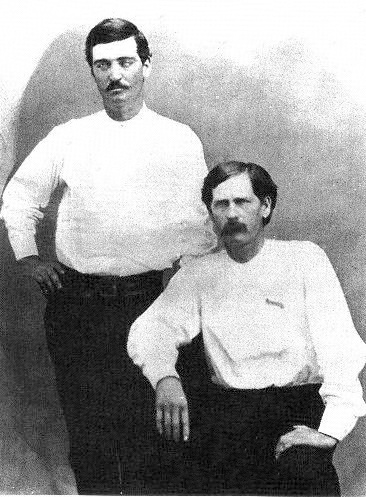

A Dodge City photograph from 1876 of Bat Masterson, left, with Wyatt Earp.

The Earp party were all tried for killing, and after a preliminary examination lasting several weeks, during which more than a hundred witnesses were examined, they were all exonerated. There were at this time two other outlaw bands in the country, who, when they heard of the killing of the McLaury brothers and Billy Clanton, swore to wipe out the Earp family and all their friends. They had no notion, however, of giving the Earps any more battles in the open. In the future, killings would be done from ambush, and the first one to get potted by this guerrilla system of warfare was Virge Earp, the City Marshal. As he was crossing one of the most prominent corners in Tombstone one night he was fired upon by some one not then known, but who was afterwards learned to be “Curly Bill,” was was concealed behind the walls of a building that was then in course of construction on one of the corners. A shot-gun loaded with buck shot was the weapon used. Most of the charge struck Verge in the left arm between the shoulder and elbow, shattering the bone in a frightful manner. One or two other shots hit him but caused no serious injury. He was soon able to be about again, but never had any use afterwards of his left arm. As a matter of course the shock he sustained when the buck shot hit him caused him to fall, and the would-be assassin, thinking he had turned the truck successfully, made his escape in the dark to the foot-hills. The next to get murdered was Morgan Earp, who was shot through a window one night while playing a game of pin-pool with a friend.

Wyatt then realized that it was only a question of time until he and all of his friends would be killed in the same manner as his brother, if he remained in town. So he organized a party consisting of “Doc” Holliday, Jack Vermillion, Sherman McMasters and Bill Johnson, and after equipping it with horses, guns and plenty of ammunition started out on the war-path intending to hunt down and kill everyone he could find who had had any hand in the murder of his brother Morgan and the attempted assassination of Verge. Wyatt had in the meantime learned that Pete Spence, Frank Stillwell, and a Mexican, by the name of Florentine, were the three who were interested in the killing of Morgan. Pete Spence had a ranch about 25 miles from Tombstone near the Dragoon Mountains, which was, in reality, nothing more than a rendezvous for cattle thieves and stag robbers.

There were at this time two other outlaw bands in the country, who, when they heard of the killing of the McLaury brothers and Billy Clanton, swore to wipe out the Earp family and all their friends. They had no notion, however, of giving the Earps any more battles in the open. In the future, killings would be done from ambush …

Wyatt and his party headed straight for the Spence ranch as soon as he left Tombstone on his campaign of revenge. He found only the Mexican when he reached the ranch, and after making some inquiry as to the whereabouts of Spence, and learning that he had left early that morning for Tombstone by a different route from the one the Earps had traveled, preceded, without further ceremony, to shoot the Mexican to pieces with buck shot. They left the greaser’s body where it fell, and returned to Tombstone, where they expected to find Spence. He was there all right enough, but seeming to anticipate what Wyatt intended on doing, had gone to the sheriff, who was not on friendly terms with the Earp faction, and surrendered, having himself locked up in jail.

Wyatt and Holliday immediately gave chase to Stillwell and succeeded after a short run in overtaking him. He threw up his hands and begged not to be killed, but it was too late.

Of course, Wyatt had to let him go for the time being, and was getting ready to start out on another expedition when he received word from Tucson that Frank Stillwell and Ike Clapton were there. Wyatt and “Doc” Holliday immediately started for Benson, where they took the train for Tucson which was about 160 miles farther south. Both were armed with shot guns, and just before the train came to a stop at the Tucson station, Wyatt and Holliday, from the platform of the rear coach saw Clanton and Stillwell standing on the depot platform. They immediately jumped off and started for the depot, intending to kill them both, but they were seen coming by the quarry who had evidently been made aware of Earp’s movements and were on the lookout at the station. Clanton and Stillwell started to fun as soon as they saw Wyatt and Holliday approaching, Stillwell down the railroad strack and Clanton towards town. Wyatt and Holliday immediately gave chase to Stillwell and succeeded after a short run in overtaking him. He threw up his hands and begged not to be killed, but it was too late. Besides, Wyatt had given instructions that no prisoners should be taken, so they riddled his body with buck shot and let it lay where it fell, just as they had the Mexican. Wyatt and Holliday then returned to Tombstone, thinking there might still be a chance to get a rack at Pete Spence, but the latter still clung to the jail.

Defying The Sheriff Of Tombstone

Meanwhile the sheriff of Tombstone had received telegraphic instructions from the sheriff of Tucson to arrest Wyatt and Holliday as soon as they showed up, for the murder of Stillwell. When Wyatt got back to town he hustled his men together for the purpose of going out after Curly Bill, whom he believed to be the man who had shot Verge from ambush. When the sheriff and his posse reached Wyatt, the latter and his crowd were about to mount their horses preparatory to going on the “Curly Bill” expedition.

“Wyatt, I want to see you,” said the sheriff.

“You will see me once too often,” replied Wyatt as he bounded into the saddle. “And remember,” continued Wyatt to the sheriff, “I am going to get that hound you are protecting in jail when I come back, if I have to tear the jail down to do it.”

The sheriff made no further attempt to arrest Wyatt and Holliday. The next night Wyatt killed Curly Bill at the Whetstone Springs, about 30 miles from Tombstone, and just to make his word good with the sheriff, he and his party returned to town. The sheriff, however, had during his absence released Spence and told him to get across the Mexican border with as little delay as possible if he valued his life, for the Earp gang would surely kill him if he didn’t.

Much has been written about Wyatt Earp that is the veriest rot, and every once in a while a newspaper article will appear in which it is alleged that some person had taken a fall out of him, and that when he had been put to the test, had shown the white feather.

This ended the Earp campaign in Arizona for the time being. Much has been written about Wyatt Earp that is the veriest rot, and every once in a while a newspaper article will appear in which it is alleged that some person had taken a fall out of him, and that when he had been put to the test, had shown the white feather. Not long ago a story was published in the different newspapers throughout the country that some little Canadian police officer somewhere in the Canadian Northwest had given Wyatt an awful call-down; had, in fact, taken his pistol from him and in other ways humiliated him. They story went like wild-fire, as all such stories do, and was printed and reprinted in all the big dailies in the country. There was not one word of truth in it, and the newspaper fakir who unloaded the story on the reading public very likely got no more than $10 for his work. Wyatt, to begin with, was never in the Canadian Northwest, and therefore was never in a position where a little Canadian police-officer could have taken such liberties with him as those described by the author of the story. Take it from me, no one has ever humiliated this man Earp, nor made him show the white feather under any circumstances whatever. While he is now a man past 60, there are still a great many so-called bad men in this country who would be found, if put to the test, to be much easier game to tackle than this same lean and lanky Earp.

Wyatt Earp, like many more men of his character who lived in the West in its early days, has excited, by his display of great courage and never under trying conditions, the envy and hatred of those small-minded creatures with which the world seems to be abundantly peopled, and whose sole delight in life seems to be in fly-specking the reputations of real men. I have known him since the early seventies and have always found him a quiet, unassuming man, not given to brag or bluster, but at all times and under all circumstances a loyal friend and an equally dangerous enemy.