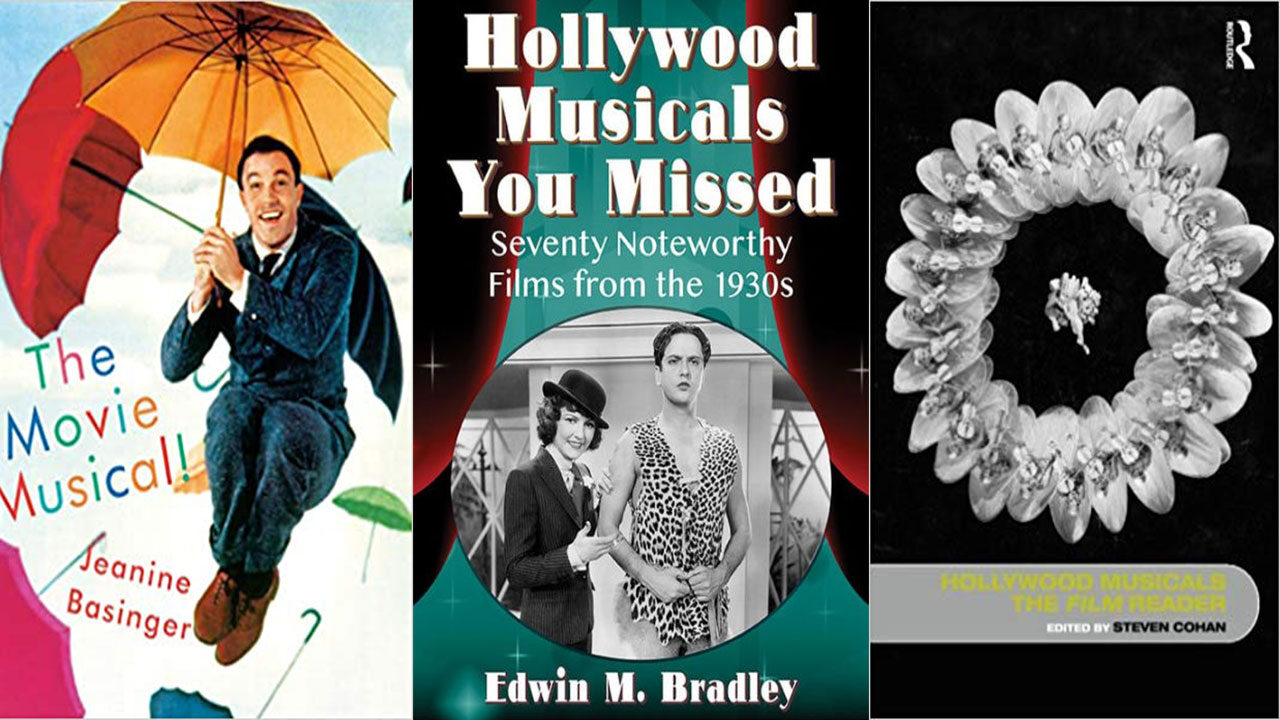

• The Movie Musical!

By Jeanine Basinger

(2019, Knopf) 656 pages, with photos

• Hollywood Musicals

By Steven Cohan

(2020, Routledge) 218 pages, with photos

• Hollywood Musicals You Missed: Seventy Noteworthy Films from the 1930s

By Edwin M. Bradley

(2020, McFarland) 306 pages, with photos

In a scene from the 1939 Gene Autry two-reeler Rovin’ Tumbleweeds, Smiley Burnette and the Pals of the Golden West sing about being locked up for crossing county lines in search of jobs after a flood destroys their homes. “On the Sunny Side of the Cell” lasts for only sixty seconds, but their song memorably ironizes the plight of those who find themselves on the wrong side of the law:

They’ve got us in jail but we don’t give a hoot

’Cause all of the service is swell

We have an enclosure/with southern exposure

We think it’s a dandy hotel

We’re taking it easy/and doing it well

On the sunny side of the cell

They feed us for nothin’/and throw in a bed

It’s better than riding the rail

Everything’s rosy/we’re comfy and cozy

What this country needs is more jails

We’re taking it easy/and doing it well

On the sunny side of the cell

We don’t have to trouble/to find out the time

We know we have plenty to spare

Well why should we worry/we’re not in a hurry

’Cause we’re not a-going somewhere

We’re taking it easy/and doing it well

On the sunny side of the cell

As their harmonies fade, the sheriff wanders over and growls, “You coyotes shut up!” Directed by George Sherman and released by Republic Pictures, Rovin’ combines music, comedy, and western motifs to reference the plight of Dust Bowl migrants during the Great Depression. It is one of nearly one hundred cowboy musicals that Gene Autry starred in between the mid-1930s and the mid-1950s, roughly sixty of which costarred Smiley Burnette. While they were two of the most popular movie and recording stars of their generation, fewer than 3,000 people have viewed the song on YouTube, and the film itself offers a rarely screened slice of Americana in which Autry punches a corrupt lobbyist and presses the case for higher taxes. The fact that Rovin’ has a political edge may surprise those who subscribe to the view that the genre is inherently escapist. But there is a sizable gap between what we think we know about the studio-era film musical and what actually unfolds in the many hundreds of song-and-dance pictures that were released by major and minor studios in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s.

As the heyday of the film musical recedes further into the past, historians have mainly focused on a subset of movies that have come to epitomize the genre as a whole. About two dozen musicals—films like Top Hat (1935), Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), and Singin’ in the Rain (1952)—account for the lion’s share of what has been written on the subject. The genre also comes with a standard narrative, one that frames the musical’s rise and fall as a series of critical junctures, from the emergence of sound technology in the late 1920s and the success of backstage musicals in the early 1930s to the MGM-driven Golden Age and the challenges posed by television and changing cultural tastes from the late sixties onwards. Most surveys faithfully reproduce this narrative, and with it the field’s fixation on a relatively small contingent of actors, directors, studios, and movies.

As the heyday of the film musical recedes further into the past, historians have mainly focused on a subset of movies that have come to epitomize the genre as a whole. About two dozen musicals—films like Top Hat (1935), Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), and Singin’ in the Rain (1952)—account for the lion’s share of what has been written on the subject.

In different ways, the books under review offer alternative perspectives on what is arguably the most polarizing of film genres. All three are by established film historians who have written extensively on specific eras and themes. Steven Cohan is a professor emeritus at Syracuse University whose approach is informed by poststructuralism and queer theory; Jeanine Basinger is the Corwin-Fuller Professor of Film Studies at Wesleyan University, and one of the country’s most celebrated writers on film; and Edwin Bradley is a curator and archivist who has penned several books on early cinema history. Like many scholars who write on movie musicals, they are devoted fans as well as serious researchers. As Basinger admits, “I was raised on musicals, and I love them,” adding that “I was drawn to the adult emotions implied in the songs and dances, to which, because they were only songs and dances, a child was allowed access.” Cohan and Basinger are polished stylists, and their latest works nicely encapsulate the genre for anyone who enjoys watching Turner Classic Movies (TCM) and is curious about how historians and theorists have analyzed canonical and lesser-known films. By comparison, Bradley’s prose is uneven and sometimes belabored. Yet of the three texts only Hollywood Musicals You Missed opens up fresh lines of inquiry.

Writers on film musicals invariably confront the problem of defining the genre, which Cohan suggests lies somewhere “on a continuum with dramas having some musical sequences at one extreme and biopics and documentaries about musical performers and composers at the other.” Those who take the long view must also wrestle with the genre’s inexorable decline and the degree to which mass audiences that once embraced on-screen singing and dancing have largely turned their backs on its mannerisms and tropes. As Basinger notes, for all its faults, the studio system “kept superb musicians, composers, and arrangers under contract” and “nurtured real singers and dancers.” Once the system collapsed, “it became much harder to make a musical” and “most of the ones that were [made] kept to a simple tradition of Broadway adaptation, documentary, animation, or biopic.” The obvious exception, La La Land (2016), is an “academic exercise” that “doesn’t own your heart,” she says. Basinger further suggests that the “No Dames!” number from the same year’s Hail Caesar! is “more fun (and more authentic) than anything in La La Land” by paying “homage to earlier movies and famous movie dancers without making it look like stealing or a weak imitation.” Yet not even the fabulous Coen Brothers are in a position to resuscitate an entire genre.

Cohan’s book is less ambitious than Basinger’s in terms of its historical sweep but is more assertive in its use of visual and literary theory. He identifies “five different approaches that have dominated film scholarship”: the genre’s utopianism; its conflation of mass art and folk art; the dual-focus emphasis on prospective romantic partners; the genre’s camp aspect; and the ways in which musicals “link gendered identities to cross-sections of race, ethnicity, nationality, and class.” The first three approaches are associated with the work of writers like Rick Altman, Jane Feuer, and Peter Wollen, who helped introduce postmodern theorizing to film studies in the 1970s and 1980s, while Cohan’s concern with questions of gender, race, sexuality, and intersectionalism draws on more recent contributions to the humanities and the interpretive social sciences. All of these approaches offer valuable points of entry into the film musical, but only the final approach would be unfamiliar to the contributors to Altman’s groundbreaking collection Genre: The Musical (1981). One of the strongest features of Cohan’s guidebook is the way it applies these five sets of theories to individual films, such as Stormy Weather (1943) and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954). While each of his chapters refer in passing to lesser-known films, none of his featured picks are particularly surprising.

Writers on film musicals invariably confront the problem of defining the genre, which Cohan suggests lies somewhere “on a continuum with dramas having some musical sequences at one extreme and biopics and documentaries about musical performers and composers at the other.” Those who take the long view must also wrestle with the genre’s inexorable decline and the degree to which mass audiences that once embraced on-screen singing and dancing have largely turned their backs on its mannerisms and tropes.

Basinger’s The Movie Musical! eschews specialist terminology but has explicitly revisionist ambitions. As she rightly points out, Al Jolson’s The Jazz Singer (1927) was not the first film musical; there was not nearly as big a slump in musical filmmaking in the early 1930s as most accounts assume; Busby Berkeley was just as capable of choreographing genuine dancing as he was arranging bodies in complex patterns; and Jack Pasternak and Joe Cummings contributed almost as much to the MGM musical as the legendary Arthur Freed. She calls attention to some truly obscure musicals, such as Melody Cruise (1933), Murder at the Vanities (1934), and Tear Gas Squad (1940)—all three of which I now have on my to-do list. She also makes a convincing case for sympathetically revisiting the aquamusicals of Esther Williams, whom she describes as “more of a female role model than has ever been properly acknowledged.” Basinger even has nice things to say about Sonja Henie and other figure skaters, such as Vera Hruba Ralston, who starred in now-forgotten movie musicals in the forties. But she places far too much emphasis on the notion that “the point of a musical” is to “provide an uplifting entertainment through musical performance,” and her claim that Singin’ in the Rain appeals to many viewers because it is a “simple” movie is unfathomable.

The 1930s is an intriguing decade from the perspective of musical film studies. The percentage of films from this period that are rarely screened or altogether unavailable is much higher than is the case for subsequent decades. Unvarnished expressions of racial hostility are abundant and yet depictions of gender and sexuality can be more fluid and unpredictable. The pre-Code era—i.e., motion pictures from the arrival of sound (aka “talkies”) in 1927 to the mandatory enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code in July 1934—is particularly rife with unexpected and sometimes jarring imagery, plotting, casting, and dialogue. While historians have recovered a number of fascinating movies from around this era—such as Hallelujah, I’m a Bum (1933) and the world’s first sci fi-musical-western, The Phantom Empire (1935)—Edwin Bradley’s new book makes it plain that there are still plenty of gems and curiosities out there. Who among us, for example, has even heard of Stingaree (1934), Swing it Professor (1937), or The Singing Cowgirl (1939)? If Bradley had asked me before the book was finished, I would have recommended that he say more about the different subgenres he works with (e.g., hillbilly musicals; films featuring teenagers; films starring opera singers; and so on), and less about how reviewers and exhibitors responded at the time to each of the “seventy noteworthy films” that he spotlights. But there is no denying the immense amount of energy that Bradley has devoted to this project. At the very least, his footnotes include many more primary sources than either Basinger’s or Cohan’s, who mostly rely on well-regarded secondary texts.

Edwin Bradley’s new book makes it plain that there are still plenty of gems and curiosities out there. Who among us, for example, has even heard of Stingaree (1934), Swing it Professor (1937), or The Singing Cowgirl (1939)?

Despite his box office successes, Gene Autry goes unmentioned in Cohan’s short book, and only receives minimal attention from Basinger. Admittedly, cowboy musicals are at best only one strand of a much larger story. But Bradley devotes an entire chapter to the western musical, and even acknowledges Smiley Burnette’s multifaceted contributions as a singer, songwriter, musician, and filmic sidekick. Rovin’ Tumbleweeds itself goes unmentioned, however. The political dimension of the Hollywood musical remains an undiscovered continent so far as the secondary literature is concerned.