In 1990, playwright Pearl Cleage penned a devastating essay responding to Miles Davis’s autobiography, specifically, to his numerous admittances that he had beaten his wives and partners. Cleage, both enraged and stunned by his revelations, questioned Davis’s continued status as a genius in light of his “self-confessed violent crimes against women,” asking, “Can we continue to celebrate the genius in the face of the monster?”[1] Particularly in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Davis carefully cultivated an image of masculine, cool mastery that appealed to a wide and interracial audience. As Gerald Early notes, Davis was publicly proclaimed as a genius and symbol for masculinity, and “he reveled in this sense of himself as a master.”[2] The recent film Miles Ahead explores the extent to which jazz audiences continue to struggle with Miles Davis. How can we admire the music while condemning the actions of the man?

Rather than rehash the historical accuracies/inaccuracies of the film, I focus on the central role Frances Taylor, the trumpeter’s second wife (together ca. 1957-1968), plays in the film, particularly as it relates to Davis’s so-called genius.[3] Taylor exists prominently in frequent flashbacks from the film’s present-day in 1979 to the late ’50s/early ’60s. Throughout the film, Davis’s sense of self and his ability to communicate musically is intimately connected to his relationship with Taylor. Without Taylor, the film initially suggests, Davis has lost the power to create a simultaneously innovative and authentic sound.

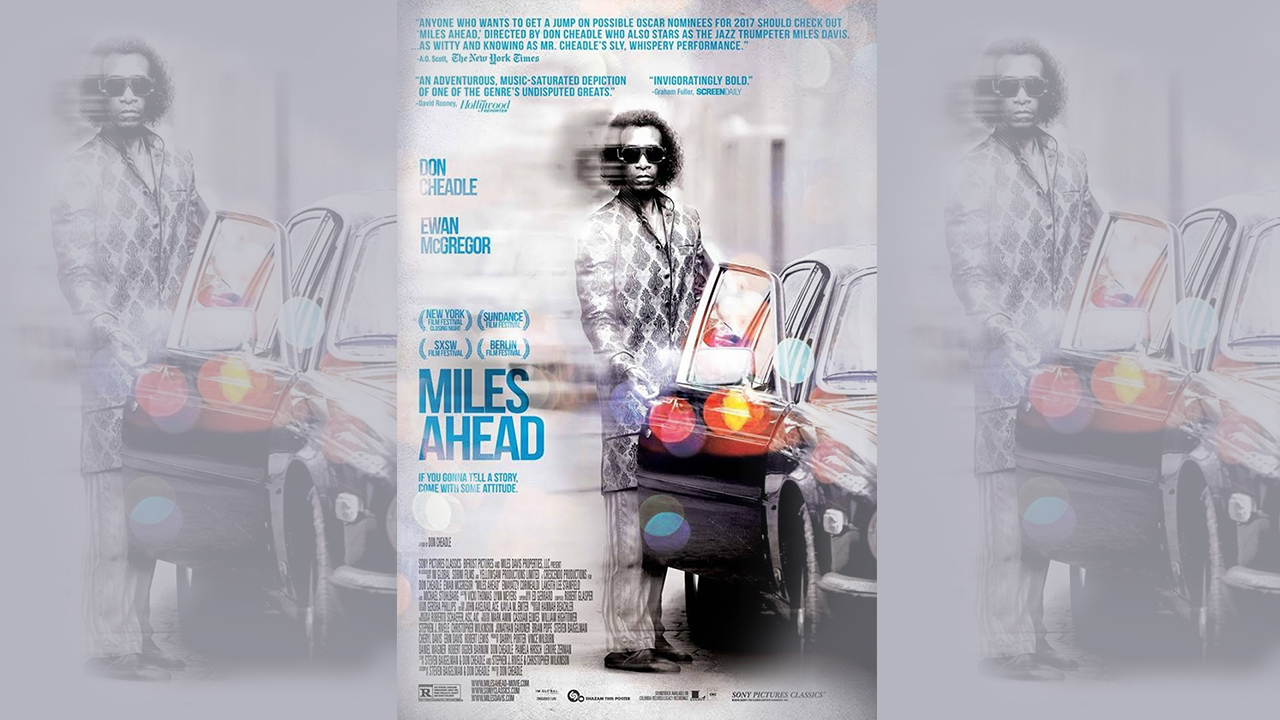

Taylor begins as the object of Davis’s desire, initially someone else’s date, but won over by Davis’s cool and confident charm. In her second scene in the film, Taylor invites Davis to see her dance (in his autobiography, Miles explains that Frances was “on her way to being a superstar”).[4] In this dance, Taylor’s control over her audience of men is obvious. Yes, her body is an object of male desire, but Taylor exercises her own power over every man in the room. She later explains to Davis why she loves to perform, telling Davis that she derives pleasure from holding the audience in the palm of her hand, and she rises from the bed to dance, demonstrating her influence and power.

Without Taylor, the film initially suggests, Davis has lost the power to create a simultaneously innovative and authentic sound.

Indeed, Davis understands exactly what Taylor means and, discomforted by the power she exerts over him in this scene, he abruptly leaves her dancing in the bedroom and picks up his trumpet, performing for her, exerting his dominance over her. Miles makes this clear in his autobiography, explaining, “A lot of black women don’t know how to deal with an artist—especially them old-timey ones, or those who are deep into their careers. An artist might have something on his mind at any time. So you just can’t be fucking with him and taking him away from what he’s thinking or doing.”[5] Regarding Taylor specifically, Davis explained that, “I just wanted her with me all the time. But she would argue about that shit with me, tell me that she had a career, too, that she was an artist, too.”[6] For Davis, artistry and power both lay solely with him.

In other scenes in which Taylor threatens to exert power over Davis, Davis takes steps to control her:

When she is on a successful European dance tour, Davis gets her to quit through emotional blackmail, saying, “Let’s have a real, serious talk about getting married when you get back.” Taylor leaves the tour immediately.

In another scene, Taylor marches into an NYPD jail and successfully manages Davis’s release after his infamous 1959 Birdland beating by two members of the NYPD. Afterward she bathes his wounds, asking, “Isn’t that better?” Davis’s response? “I want you to quit dancing. You’re my wife now, your place is with me. I know it’s a sacrifice.” Though Taylor clearly does not want to quit (she had a role in West Side Story at that point), she does.

When Taylor confronts another woman calling Davis on their home phone, Davis orders Taylor to “Stay off the damn phone.” Taylor, clearly at her limit, retaliates, “I make your life beautiful … I gave up everything for you! I’m the prize here. You never played better than when you were with me. I deserve better than this!” In the film, Taylor escalates the argument (problematically suggesting her own culpability in her abuse), first throwing a wine bottle at Davis before Davis hits her, and the two collapse onto a coffee table, breaking it into pieces.

Even beyond his actions and music, the film presents Davis as a genius by imbuing his statements with importance and special meaning. The words Davis speaks in the film are often lifted straight from the pages of his autobiography—which was heavily edited by Quincy Troupe (and is treated with healthy skepticism by most scholars in the field). A look at the interview transcripts between Troupe and Davis demonstrates the often incoherent rambling statements that Troupe, and now screenwriters Steven Baigelman and Don Cheadle, cut through to dissect only the most memorable lines. But while Davis’s lines are constant reminders of his genius, Taylor’s are often little more than stereotypical lines that could be said by any partner of a successful musical male “genius.”

At the end of the film, the women who made Davis are pushed even further from the center, and Davis is preserved within a familiar narrative celebrating individualistic masculine genius at all costs.

Ultimately, the film responds to Cleage’s demand—that we acknowledge Davis’s record with women—but does so by asking the audience to understand Miles’s perspective, by giving Davis’s words importance, and by positioning him as a genius. Taylor may win our sympathy, but only at the cost of Davis’s genius. Notably, all of the other women who made Davis, including Irene Cawthon Davis-Oliver, Juliette Gréco, Betty Mabry Davis, Jackie Battle, Marguerite Eskridge, and Cicely Tyson, are completely excised from Davis’s remembrances in this film.

Who made Miles Davis? Though the film presents Davis’s “sound” as inextricably linked with Taylor, by the end of the film, the audience may feel that while Taylor contributed to Davis’s “cool” period sound, his “classic” sound, she was simply an obstacle to his continued greatness. At the end of the film, Davis relies on a hip young trumpeter he meets in his 1979 escapades to forge a new stylistic approach. The comparisons between Davis and this trumpeter, played by Keith Stanfield and known in the film as “Hype,” abound. “Hype” is a drug addict attempting to make his way in New York, and is married to a woman named Irene, with whom he has two children; in other words, “Hype” is Miles Davis before he meets Frances. As the two collaborate musically, the flashbacks to Davis ’s life with Taylor disappear, resulting in the implication that Davis alone made Miles Davis; he is his own auteur. At the end of the film, the women who made Davis are pushed even further from the center, and Davis is preserved within a familiar narrative celebrating individualistic masculine genius at all costs.

And thus, as Davis ultimately finds his way by pushing past his obsession with Taylor and focusing on himself, the audience is left with the same question Cleage asked 25 years ago: “Can we continue to celebrate the genius in the face of the monster?”