I have now visited the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum four times. My trip last month was quite special.

I grew up in a small farming community in 1950s Illinois. My father was both the first lawyer in the town and the first Jew in the town. As a toddler, I was severely asthmatic. One night I almost died while being rushed to the hospital.

Two years later I wanted to play baseball with the other boys. My problem was not asthma. My problem was that I could not hit at all. At age 11, I needed to come up with a new approach. I painted a strike zone on a fence at the high school baseball field and kept throwing until I could hit the target consistently. One year later I was the best pitcher in the Plainfield Little League. All this meant was that I could throw a baseball over the plate and into the strike zone.

I liked basketball as well. I could shoot but could not run or jump well. In seventh grade our basketball team played several preseason games against the so-called Negro schools- K D Waldo in Aurora, Gompers and Washington in Joliet, Fairmont in Lockport. We lost every game, but what I noticed the most were the dark and dilapidated gyms, the rusty lockers, and the cracked tiles. Once I asked my mother, “How come the Negro boys have such lousy gyms although they are excellent players?” My mother did not know what to say.

One year later, Dr. Leonard Katzin came to our house one night to speak with my father. Maybe he came at night because he and my father were both afraid that if anyone saw both Jewish men who lived in Plainfield talking with each other, it would be proof of the worldwide Jewish conspiracy.

Leonard Katzin asked where I was going to high school. My father replied, “Plainfield High.” Dr. Katzin, a nuclear physicist, responded with, “ Sam, if you send Burton to Plainfield High School, he will never amount to anything.” He noted that his brilliant daughter Martha would be attending Joliet Township High School despite the cost of out of district tuition. My father just nodded. The Katzins lived in the town but we were part of the town. There was no way the only lawyer in Plainfield could give the local high school a no-confidence vote.

We lost every game, but what I noticed the most were the dark and dilapidated gyms, the rusty lockers, and the cracked tiles. Once I asked my mother, “How come the Negro boys have such lousy gyms although they are excellent players?” My mother did not know what to say.

Most of the classes at Plainfield High were easy for me. They were designed for boys who would become farmers or soldiers and girls who would become homemakers. But one class was very challenging. Mrs. Niehaus, my Latin teacher, assigned an hour of homework each night. She insisted every translation in class be perfect. After tenth grade, Mrs. Niehaus took us to the National Latin Club convention in Kansas. I finished third in the National Latin II vocabulary contest and started to think that Dr. Katzin’s prediction for me could turn out to be inaccurate.

Meanwhile, my baseball career was progressing nicely. One day I came home to tell my father, “I just won my first varsity game. My name will be in the newspaper tomorrow.” My father replied, “Don’t you have a math test tomorrow?” My father knew that it was important for me to be involved in sports. He also knew I had no fastball at all. During my senior year, two Illinois colleges offered me baseball scholarships. But neither was strong academically. I wanted to attend Carleton College in Minnesota, later described in a popular college guide as “the unknown crown jewel in American higher education.” It took a prominent Chicago attorney to convince my father that Carleton was worth its $2,000 per year cost, double what the University of Illinois charged.

I loved pitching for the Carleton Knights, but knew my baseball career would be over at graduation. I decided to become an inner-city high school teacher. This was an unusual decision for a young man who was going to be declared IY by the local draft board. Without a declaration of war in Vietnam, asthmatics were excused. My decision was problematic as well. A number of black militants were demanding “no white teachers in our schools.” However, my decision received unexpected support. Yvonne Jones, a black classmate from Indianapolis, told me that her mother said, “We desperately need good teachers of all colors in our schools.” Rey Harp, a black classmate from Chicago, took me to visit DuSable High School where I saw police in the schools for the first time. I also saw signs of hope. I could see the pride Rey’s teachers had in him.

I went to one of my professors, a Jewish folklorist named Roger Abrahams, for advice. He told me to teach with dedication and humility, adding, “If you are sincerely committed, your efforts will be appreciated.”

These words were prophetic beyond my imagination. After 35 years of teaching history and social studies at two New Haven High Schools, I was named Connecticut Teacher of the Year. New Haven’s African-American community strongly supported me. One year later, a month before my retirement as a high school teacher, Quinnipiac University granted me an honorary doctorate. This just does not happen to high school teachers. I remember my surprise every time I think about this moment.

Bob Tappan, a legendary picker, sold me the shade for $250. We both knew it could have been made in the late 1960s, just before the Negro Leagues shut down for good. If that had been the case, $250 would have represented fair market value. It turned out the shade was produced in the 1920s, making it quite valuable. How valuable I do not know and I may never find out for sure.

A few months ago something even better happened. Jahana Hayes, my student teacher in 2004-2005, was named the National Teacher of the Year for 2016-2017.

If that were not enough, one of my grandsons, Colby O’Connor, turned out to be a good Little League pitcher. I have spent hours watching his games. My wife Myra has become a baseball fan. She and I also enjoy collecting antiques.

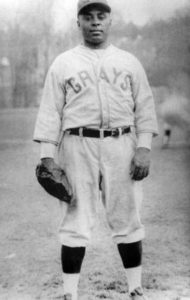

Oscar Charleston

Four years ago, I was in a local antique shop called Salvage Alley. A black window shade with gold lettering was hanging from the rafters. The shade said, “Negro League Baseball Tickets Sold Here.” Bob Tappan, a legendary picker, sold me the shade for $250. We both knew it could have been made in the late 1960s, just before the Negro Leagues shut down for good. If that had been the case, $250 would have represented fair market value. It turned out the shade was produced in the 1920s, making it quite valuable. How valuable I do not know and I may never find out for sure. The average of the three appraisals I have received is about $4,500, a number I believe is too low.

The monetary value of this precious item does not matter. It did take me a while to come to this conclusion. I still believe this item could bring a princely sum at auction—but not enough to make a difference in my life, or the life of my heirs after I depart this earth. What really matters is that the window shade does not belong in private hands. It needs to be on display. In 2013, I called both the Negro League Hall of Fame in Kansas City and the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, leaving two voice mails that mentioned my intention to donate the item. To my shock and chagrin, I did not receive a return call from either.

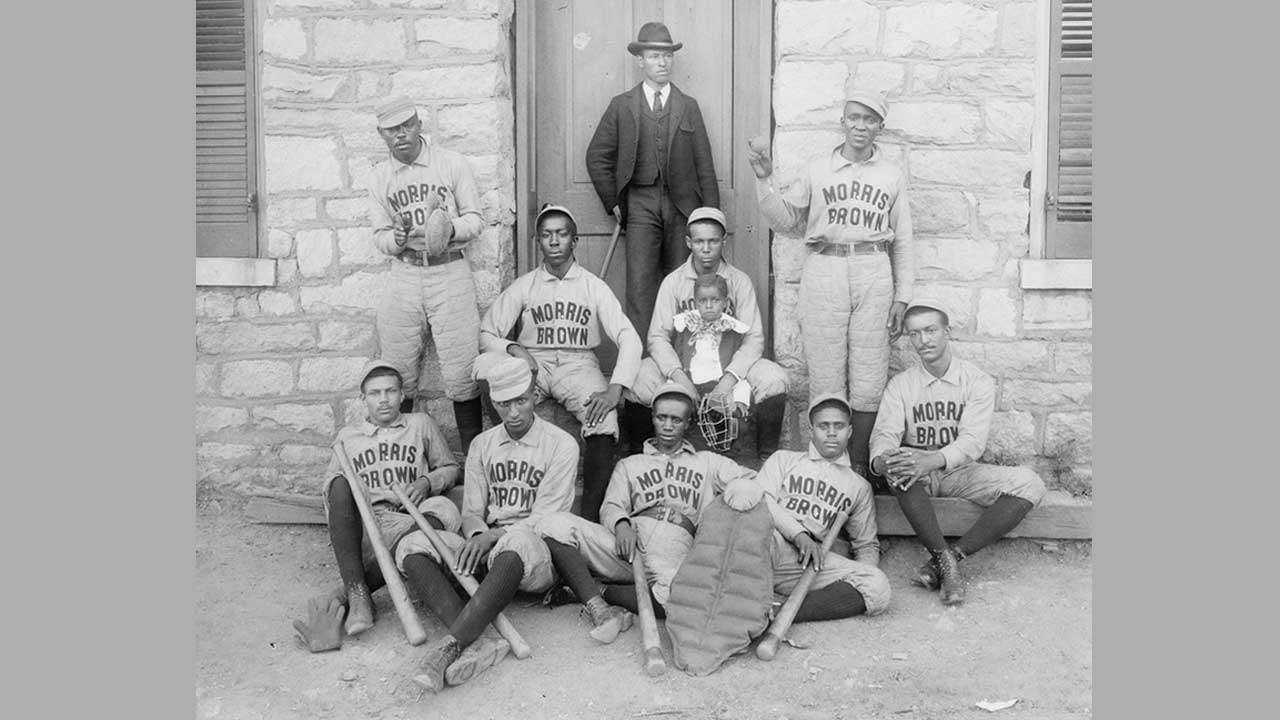

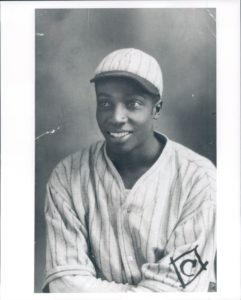

In 2016, I decided to try again. My friend Will Sherman found a picture of a similar item on the Internet. I tentatively concluded, erroneously as it turned out, that both Halls of Fame possessed a window shade similar to mine. It still seemed like another phone call or an email was appropriate. I received a positive response about the window shade from the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Simply put, it belongs there. It represents Oscar Charleston, Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson, and other great black ballplayers who were denied the opportunity to play our national pastime at the highest level. As a teacher, I want it in Cooperstown for another reason. The majority of the visitors to Cooperstown are white. They need to see it. The simple shade has a powerful message.

Cool Papa Bell

The window shade certainly is a simple item. In that respect, it represents my life—a simple life. Although it took me years to realize it, I wanted to become like Mrs. Niehaus. She taught me and inspired me and it did not make any difference to her that I was Jewish. I had also tried to teach and inspire all my students over a period of 45 years. The majority of my students were African-American. I had tried to be supportive of them and they had been supportive of me. There was no way I could make a profit on an important piece of African-American sports history.

The perfect opportunity to make the donation came in August 2016. Colby’s team, the Orange Crushers, was playing in a tournament at the Cooperstown Dream Park. The team went 6 and 2 and Colby won the game he pitched—giving up no walks. The next morning Myra and I met with Sue MacKay, the acquisitions director of the Hall of Fame. An hour later, the window shade had a new and permanent home. When Myra and I then went upstairs to see the Negro League exhibit, I was very pleased the window shade will be there soon. Their exhibit was filled with pictures and posterboards, but contained very few artifacts.

After we made the donation, my Carleton classmates Harry McLachlan and Brad and Cathy Lewis joined Myra and me for lunch in Cooperstown. I will never forget this wonderful brief vacation. It brought my life full circle.

Josh Gibson

The past month has been a time of reflection for me. I realize how very fortunate I have been over the years. I have a loving wife and a loving family. I enjoyed teaching enormously. I have a number of friends and am in pretty good health. Through good luck and some good decisions, Myra and I are able to spend our winters in Florida. My favorite team—the Chicago White Sox—even won the World Series a decade ago. It feels as if all the things I lack—wealth, status, and power—are unimportant. I even thought about Dr. Katzin’s prediction for me. Maybe I did not become prominent as his daughter Martha did, who became the first woman to receive a Ph.D. in math from Princeton. Maybe the consensus among many educated Americans is correct: a person who becomes a high school teacher has not amounted to much. But I do not see it that way. I believe my life has had purpose and meaning, making me very lucky and blessed.

I am reluctant to ask for more for myself. But I will ask for something for an old family friend.

Don Kinley gave me my first professional haircut in 1956. He had just returned from the military. He was 20 years old. Don had a small television set near his barber’s chair. He watched baseball with intensity but still managed to give perfect haircuts.

Don was and still is a diehard fan, the kind of guy who never gives up on his team. He is now 80 years old.

Maybe, just maybe, the Cubs will be World Champions this November.