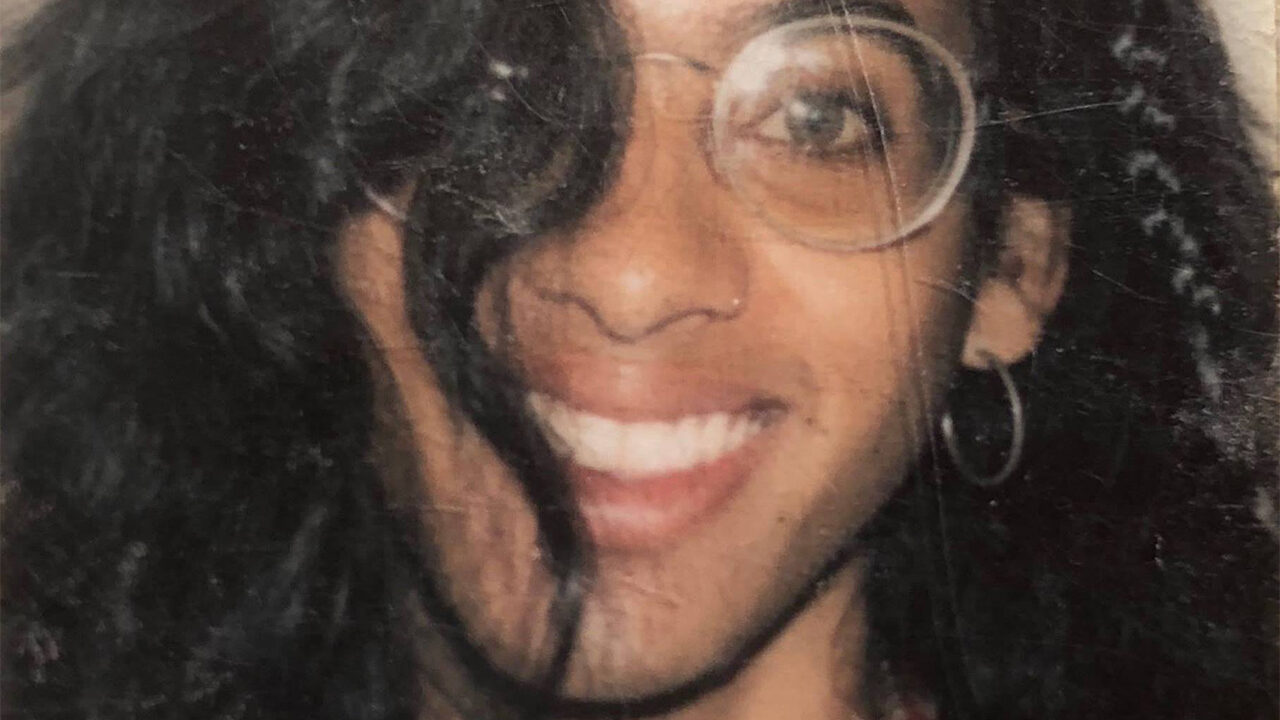

0. Having a bad hair day

When I returned home from my freshmen year at college with long and unbound hair, my freak flag flying, and ears pierced (both of them), my first-generation Indian-Hindu parents were utterly aghast, bewildered, and astounded. My untamed mane made their hair stand on end. They urged me to comb it out, rein it in, and put it in a ponytail. In fact, I came within just a hair of shaving the whole thing off …

Why were my Hindu parents so disturbed by my new do? Why had, in my view, my symbol of unfettered freedom and emancipation from domestication caused so much grief and consternation?

1. The Dharma and Karma of Hair

Hair is an enormously important symbol in Hinduism and, more broadly, among South Asians. How it is cut, kept, braided, oiled, shaved, colored, and sometimes even plucked had (and clearly still has) significant meaning, weight, and even consequence for Hindus. It is thus reflective of one’s dharma (law, duty, obligations, rules and regulations) and karma (the mechanism of causality that links past actions with future actions and even lives). From the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s perspective, hairstyle in Hinduism definitely (and perhaps archetypally) “acts to establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence …” ¹

To explore this, I will examine the dharma of hair in Hinduism. These rules (for both men and women), I will show, like so many prescriptions and obligations in Hinduism, are almost entirely context dependent. In fact, all dharma (hair dharma included) in Hinduism is dependent on context. While it may seem as if there are rules that apply across the board and that dharma is a kind of moral universalism, dharma is actually prescribed according to one’s gender, age, stage of life, and, of course, varṇa/jāti (class/caste) and hairstyle is no exception. The dharma concerning hair for women is especially tangled and challenging and far more demanding than it is for men.

So, what is the dharma of hair for women?

2. A Hair-Raising Tale: The Case of Draupadī in the Mahābhārata

Hair is not insignificant in the Mahābhārata, the epic Hindu tale composed in Sanskrit more than 2000 years ago, concerning warring families and the reestablishing of dharma (Geertz’s “order of the universe”). The Mahābhārata provides both a model for and model of hair mores that still are relevant and influential today. When women in the Mahābhārata unbraid their hair, for example, this act and display is symbolic of their mourning, a visual indicator that one has become a widow, and even a sign that a woman is undergoing a purification that occurs during the process of menstruation. In the Mahābhārata, keeping hair un-coiffed is not an auspicious sign. In all these cases, dharma has become mussy and disrupted, if not completely tangled.

From the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s perspective, hairstyle in Hinduism definitely (and perhaps archetypally) “acts to establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence …”

One of the most egregious and infamous moments in the monumental poem is centered on Draupadī, the wife of the five Pāṇḍava brothers, a queen who is described in the Epic as the most beautiful woman of the times. In a distressing scene, she is dragged into the sabha (men’s hall) by only her hair after she is lost in a wager during a game of dice by Yudiṣṭhira, one of her five husbands. This is especially ironic because in the Mahābhārata, Dharma is both an ethical ideal as well a deity, a deity who is the father of Yudiṣṭhira. How could the son of Dharma act so adharmically? To make matters and the humiliation of the hair dragging exponentially worse, Draupadī had secluded herself to her quarters as she was menstruating, which is regarded as a private ritual observance of purification.² It is worthwhile here to cite this especially dreadful, moving, and telling passage from the Mahābhārata verbatim:

And quickly the angry Duḥśāsana

Came rushing to her with a thunderous roar;

By the long-tressed black and flowing hair

Duḥśāsana grabbed the wife of a king.

The hair that at the concluding bath

Of the king’s consecration ceremony has been sprinkled

With pure-spelled water, Dhṛtarāṣtra’s son

Now caresses with force, unmanning the Pāṇḍus.

Duḥśāsana, stroking her, led her and brought her,

That Kṛṣṇā of deep black hair, to the hall,

As though unprotected amidst her protectors,

And tossed her as a wind tosses a plantain tree.

And as she was dragged, she bent her body

And whispered softly, “It is now my month!

This is my sole garment, man of slow wit,

You cannot take me to the hall, you churl!” ³ (Mahābhārata 2.60.25-32)

In this revealing passage we learn that Draupadī had left her hair unbraided and unrestrained to show that she is menstruating and, therefore, in the process of purifying. By dragging her by her hair in this way, Duḥśāsana has committed the worst kind of trespass and violence against a woman, and, for that matter, dharma itself, and has disrupted her process of purification. Unbound hair for women is not expressive of adolescent/teenage or sexual freedom, as it is here in the United States. Rather, it flags a woman as actively engaged in purification. Duḥśāsana, thus, is responsible for two kinds of violence – the first, interrupting Draupadī’s purification, and the second, dragging her by her hair, a despicable act that is implicitly forbidden. ⁴

In the Veṇisaṁhāra, “Binding up of the Braided Hair,” an especially gruesome nātaka (play) and expansion of the Mahābhārata composed in the seventh century CE by Bhaṭṭa Nārāyaṇa, Draupadī takes a vrata (vow) not to wash or braid her hair until Bhīma, another one of her five husbands, has killed Duḥśāsana (also known as Suyodhana here) and then binds her hair with his bloody hands. (Incidentally, Bhīma also vows to drink Duḥśāsana’s blood after killing him to avenge his wife.⁵ ) Bhīma promises Draupadī:

O Queen, this Bhīma shall tie up your hair with his hands red with the greasy clotted and thick blood of Suyodhana, whose pair of thighs will be mangled by the blow of my terrible mace, whirled round by my throbbing arms.⁶

And then, after Duḥśāsana has been killed, Draupadī addresses Bhīma:

May my lord tie up my tresses loosened by Duḥśāsana with the hand wet with Duryodhana’s gore…this was promised by my lord … Bring me then wreaths of flowers; arrange my hair into braid.”⁷

Her “extended symbolic menstrual defilement”⁸ is, in her eyes, able to end. She is transformed, made pure, cleansed, ironically with a body fluid that is paradigmatically and dangerously aśuddha (impure). Only then can Draupadī braid and oil her hair and, in this way, restore order to the universe. Here, violence committed upon her when she was most vulnerable and transitional is righted by yet another kind of violence that is inextricably bound to her severe vrata. She may then braid and bind her hair. Hair, here, is bound up with so many distressing and, finally, triumphant symbols and storylines. Hair styling on the microcosmic level, moreover, reflects and coincides with the state of affairs on the macrocosmic level.

The dharma concerning hair for women is especially tangled and challenging and far more demanding than it is for men.

It would seem that leaving my hair unbound, flowing, as I did in front of my first-generation Indian-Hindu parents, was a cultural faux pas of the highest order, assuming, of course, that they were reminded (consciously or subconsciously) of this moving and horrifying story. If they were reminded in this way, then my unbound hair unnecessarily (and unintentionally) evoked painful moods and motivations that threatened the very stability of the universe—well, at the very least, my parents’ suburban universe.

3. The perfect hair and the perfect wife

She wore scarlet begonias, tucked into her curls

I knew right away she was not like other girls

—Grateful Dead, “Scarlet Begonias” ⁹

It will come as no surprise that detailed accounts about the hair of an ideal woman, in this case a potential (and perfect) wife, are found in the Mānavadharmaṡāstra, The Law Code of Manu, a so-called “Brahminical”/Sanskritic “Classical” text focused on context-dependent dharma. ¹⁰ There is an intriguing section concerning the selection of a bride after a young man has completed his religious education, perhaps a forerunner of the well-known Indian custom of arranged marriage. It is advised that:

He must not marry a girl who has red hair or an extra limb; who is sickly; who is without or with too much bodily hair … ¹¹

And, furthermore:

He should marry a woman who is not deficient in any limb; who has a pleasant name; who walks like a goose or an elephant; and who has fine body and head hair, small teeth, and delicate limbs. ¹²

The perfect wife does not have red hair and has just the right amount of head and body hair, which, moreover, must be fine. These are characteristics which one is born with and cannot change (well, a redhead could dye her hair) and are indexed to karma (actions in previous lives and times). Depilation (by shaving, plucking, tweezing, threading, and any other method) does not entirely solve the problem since one still needs the right amount of hair (the precise amount is not defined) and, moreover, it must be fine. Even if one can meet these desiderata, grooming would be constant and may even be somewhat deceitful.

In the Mahābhārata, keeping hair un-coiffed is not an auspicious sign. In all these cases, dharma has become mussy and disrupted, if not completely tangled.

Women do not have an easy time in Hinduism with their hair. If they let it out, then it is not auspicious or it is a flag that they are menstruating (and thus regarded by the system as temporarily impure). And for some unfortunate women, whose hair is red or who possess lots of coarse body hair, they are forever unwanted.

4. The Control of Hair and Controlling the Hair

In this context, the controlling of hair, or the decision to leave it uncontrolled, is symbolic of an undesirable disorder. At the same time, uncontrolled and matted/dreaded hair can be symbolic in the Hindu universe of a male’s detachment from the prevailing and binding social order, oftentimes occurring during vānaprasthā (forest hermit), the third stage of life. Unbinding hair shows evidence of control over the body and senses and, concurrently, a severing of attachment to the body. According to Mānavadharmaṡāstra, when a man becomes a vānaprastha:

He should wear a garment of skin or tree bark; bathe in the morning and evening; always wear matted hair; and keep his beard, boy hair, and nails uncut. ¹³

The Hindu god who archetypally represents and manifests this asceticism is Śiva, the serpent-wearing, tiger skin-clothed, dreadlocked, meditating yogi. In fact, any ascetic or meditating yogi who aspires to be like Śiva would and should have uncontrolled and matted hair, show no interest in hair grooming, much less appearance, vanity and so on. Should a person in India come across such a person, whose hair is matted and who is generally unwashed, they might react with a mood of reverence and sometimes even homage may ensue. Though this style is largely permissible to men in the specified circumstances, there are a few goddesses who are depicted with unbound and disheveled hair, namely Durgā and Kālī, companions of and inextricably linked to the god Śiva.

Sometimes then, long (and unkempt) hair is permitted, so long as one is male and, of course, an ascetic who aspires to be like Śiva or is Śiva’s companion.

The person in Hinduism whose hair is the most controlled is the gṛhastha (householder), who, with the appropriate coiffed and groomed wife, is required to uphold dharma and order in the universe. To this end, according to Mānavadharmaśāstra:

He shall keep his nails clipped, his hair and beard trimmed, and himself restrained; wear white clothes; remain pure; and apply himself every day to his vedic recitation and to activities conducive to his own welfare. ¹⁴

A gṛhastha should be well groomed and should have what would be considered today a conservative, unthreatening and unimaginative hairstyle.

5. Hair Today, Gone Tomorrow

What about having one’s hair shorn in Hinduism? Is head-shaving permissible? While there are contexts in which head-shaving is permitted, there are other contexts where a shaved head is intended to evoke a painful or somber mood. Men and women have their heads forcibly shaved when they are being punished for adultery, violence or violent sexual acts. ¹⁵ For example, when adultery is committed by a Kṣatriya (the second-highest class), “his head is shaved using urine.”¹⁶ And in the context of female-female sexual assault:

When a woman violates a virgin, however, her head ought to be shaved immediately–alternatively, two of her fingers should be cut off–and she should be paraded on a donkey.¹⁷

In these and similar cases, perpetrators mirror the styles of a shaved ascetic who lives outside of the normal social system and is, perhaps, even antisocial. These criminals may even be required to live on the outskirts of the village, on the margins of the society that has rejected them, and which they also rejected through their criminal act.

It would seem that leaving my hair unbound, flowing, as I did in front of my first-generation Indian-Hindu parents, was a cultural faux pas of the highest order, assuming, of course, that they were reminded (consciously or subconsciously) of this moving and horrifying story.

But in other contexts, head shaving is not only permissible, but enjoined. According to Mānavadharmaśāstra , when men are either brahmacāris (students) or saṃnyāsis (wandering ascetics), they are supposed to shave their heads.

He should…always go about with his head and beard shaved, with his nails clipped, carrying a bowl, a staff, and a water-pot, and without causing harm to any creature.¹⁸

The brahmacāri (which I was, by the way, when I returned home to my parents’ abode), has choices: “A student may shave his head or keep his hair matted; or else he may keep his top knot matted.”¹⁹ The latter hairstyle involves shaving the head but leaving a mere tuft at the top of the head.

The brahmacāri is permitted to some degree, albeit very small, to be imaginative and creative about how he would like to be perceived in the world.

6. Tying it Together

Hair dharma in Hinduism is context dependent. While there are hairstyles that are permissible, some even prescribed or required, they must be manifested at the appropriate time and space, and even stage of life, and in accordance with gender. Shaved heads can connote lamentation for some and connote detachment and asceticism for others. Unbound hair can symbolize temporary impurity for a woman and can symbolize a disengagement from social mores. And, in one exceptionally gruesome case, unbound hair represents adharma (disorder in the universe) and, when it is eventually bound and braided, it exemplifies vengeance and the restoration of dharma.

It is indisputable that how one manages one’s hair in Hinduism has significant consequences for the hair-bearer and for the mood and motivations of those nearby.

… in one exceptionally gruesome case, unbound hair represents adharma (disorder in the universe) and, when it is eventually bound and braided, it exemplifies vengeance and the restoration of dharma.

Upon reflection, I think that my dear parents may have erred in wishing upon me the hairstyle meant for a gṛhastha which my father, of course, sported. Alas, my pāpam (bad) karma must have manifested then. I was a brahmacāri and, following my dharma, could either shave my head, keep a top knot, or let my freak flag fly.