The world was astonished recently by the sale of a presumed Leonardo painting of “Salvator Mundi” for the mind-boggling sum of $450 million. Like most media sensations, the Salvator Mundi already is fading from our brief attention. I suspect it will soon lose its claim to being an autograph Leonardo as it rejoins the some twenty other versions of the same subject … several of which also have been promoted as the “original.” While the current painting has a tenuous relationship to Leonardo, it has a rightful place in the phenomenon of Leonardo, and this is a story that is well told in Walter Isaacson’s new biography, Leonardo da Vinci. Isaacson also tells the tale of another doubtful attribution—La Bella Principessa—with an open mind and in the engrossing manner of a good mystery. As these two works suggest, Leonardo can be a slippery subject. He was a multi-faceted artist/scientist, inventor/visionary difficult to grasp in his protean totality. Walter Isaacson, however, is a reliable and voluble guide. This is a good read.

The author of Steve Jobs, Benjamin Franklin, and Einstein (among others), Isaacson is drawn to genius although he is loath to use the word lightly and only defines Leonardo’s special brand of genius late in his magisterial study. For Isaacson, what set Leonardo—as well as Steve Jobs and Franklin—apart from other people who are exceptionally smart was his creativity and an ability to blend imagination with intellect and make connections across disciplines—arts and sciences, humanities and technology. Leonardo’s facility to combine acute observation with fantasy allowed him to make unexpected leaps, relating things seen to the unseen, things known to things not yet discovered, things possible to the impossible. Leonardo was not afraid of the impossible; indeed, he wrestled with it much of his adult life, such as his efforts to devise a mechanism for solo human flight or the irresolvable problem of squaring the circle. Even in failure, he continuously advanced his prodigious learning.

One is hard-pressed to find subjects that did not interest Leonardo. Isaacson frequently points to instances when Leonardo anticipated inventions and discoveries centuries in advance.

Leonardo is the archetype of the “Renaissance Man” who was inspired by the infinite wonders of nature. He pursued studies in a myriad of fields including human, animal and comparative anatomy, botany, optics, perspective, geology, hydrology, the flight of birds and human flight, topography and maps, micro and macro technology, weapons and war machines. He was a theatrical impresario who designed lavish entertainments, complete with sets, costumes, and mechanical contrivances to amuse and occasionally enlighten the ducal court of Milan. He composed fables and indulged in picture puzzles and riddles; he spent hundreds of hours investigating the possibility of perpetual motion, the nature of perspective, light and shadows (more than 15,000 words on the subject), the proportion and movement of horses, the flow of water and the formation of vortices, which he realized were among the most powerful forces of nature, whether of air or water. As Isaacson repeatedly notes, Leonardo had an acute power of observation and an omnivorous, passionate, voracious curiosity—the author employing each of those adjectives repeatedly to capture something of the unique character of Leonardo’s engagement with the natural world.

One is hard-pressed to find subjects that did not interest Leonardo. Isaacson frequently points to instances when Leonardo anticipated inventions and discoveries centuries in advance. Many are aware of his designs for flying machines, a parachute, a tank and an early form of the Gatling gun, but even more startling is Leonardo’s anticipation of William Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of the blood, or his realization that fossils found on mountain tops were deposited there not during Noah’s flood, but because of geologic mountain-building far older than the biblical age of the earth purported to be some 6,000 years. He wondered why the sky was blue and conducted multiple experiments to test his hypotheses, yet he was confounded when it came to explaining the cause of a rainbow. That explanation had to wait for Isaac Newton; however, “not bad,” Isaacson suggests, for Leonardo to have anticipated if not quite answered something that required another two hundred years of brilliant thinkers!

Leonardo questioned everything, including all received wisdom. Every little thing was subjected to Leonardo’s ultimate test of objective observation, experiment, and scientific proof. In this, Leonardo is the harbinger of the scientific method and rational epistemology propagated by the likes of Francis Bacon, René Descartes, Benjamin Franklin, and Albert Einstein. No wonder, Walter Isaacson was drawn to Leonardo as a subject.

Early in his book, Isaacson fastens upon a curious albeit unexpected tidbit of Leonardo trivia. Among the more than 7,000 pages of Leonardo’s notebooks, Isaacson’s is particularly drawn to the many “to do” lists that Leonardo wrote to himself. On one, he discovers this odd reminder: “Describe the tongue of the woodpecker.” Astonished by the utter improbability of this notation, Isaacson asks, “who on earth would decide one day, for no apparent reason, that he wanted to know what the tongue of a woodpecker looks like?” The biographer reveals something of his brilliance as a storyteller by postponing an answer for some 394 pages, merely observing at this early moment that Leonardo “wanted to know because he was Leonardo: curious, passionate, and always filled with wonder” (5). At the very end of his book, Isaacson returns to the woodpecker’s tongue, as I will.

Early in his book, Isaacson fastens upon a curious albeit unexpected tidbit of Leonardo trivia. Among the more than 7,000 pages of Leonardo’s notebooks, Isaacson’s is particularly drawn to the many “to do” lists that Leonardo wrote to himself. On one, he discovers this odd reminder: “Describe the tongue of the woodpecker.”

“Curious,” “passionate,” “wonder,” are leitmotifs that—along with a few other words and phrases such as “powerful curiosity,” “passionate curiosity,” “relentless curiosity,” “obsessive curiosity,” “omnivorous curiosity which bordered on the fanatical” pepper and repeat themselves throughout this long but readable narrative. Isaacson is a fluent and oftentimes captivating writer, but such recurrent expressions reveal the limits of the language when he wishes to describe a person who was a “voracious seeker of knowledge.” Even a skilled biographer is occasionally stymied by his subject’s formidable talents and Isaacson is humble enough to admit his wonder. At the same time, Isaacson has a marvelous ability to pithily capture aspects of Leonardo, a “genius undisciplined by diligence” (82). He was an artist who “constructed his art on a scaffold of science” (78), and “who enjoyed the challenge of conception more than the chore of completion” (518).

Isaacson is a fluent and oftentimes captivating writer, but such recurrent expressions reveal the limits of the language when he wishes to describe a person who was a “voracious seeker of knowledge.” Even a skilled biographer is occasionally stymied by his subject’s formidable talents and Isaacson is humble enough to admit his wonder.

In contrast to writing about Steve Jobs, where he was able to tell his story fresh and for the first time—from living sources—Isaacson, in writing about a subject who died 500 years ago, was more hampered by history’s distant horizon. There are still extant some 7,200 pages of Leonardo’s notebooks, which may be only half of what the artist originally wrote. Isaacson mines this material to great effect, pointing out that, for all its rich variety, the material lacks the confessional writing and personal insights of a St. Augustine, but it is infinitely more interesting and varied than the thousands of Steve Jobs’s e-mails. Thus, it is in the artist’s notebooks that Isaacson finds his subject and some of his best material for bringing Leonardo to life. There we find banal entries made vivid as we hear Leonardo “talking” to himself: “Ask Benedetto Portinari how they walk on ice in Flanders,” or, concerning a rare book he hoped to borrow: “Maestro Stefano Caponi, a physician, lives at the Piscina, and has a Euclid.” Sometimes, the jottings are poignant, as when he sadly laments, “Tell me if anything was ever done” (88). Every year, I share one of Leonardo’s sayings with my classes: “Men of lofty genius sometimes accomplish the most when they work the least.” It is every student’s perfect excuse to procrastinate.

Even when Leonardo is writing about art, he might become distracted and scribble notes such as, “describe the placenta of a cow,” “the jaw of a crocodile.” As Isaacson rightly observes, we find such concerns amazing “mainly because we never make the effort, in our daily lives, to observe ordinary phenomena so closely” (183). And here, Isaacson is not addressing cow placentas or crocodile jaws, but thousands of other observations that Leonardo recorded in his notebooks: the fall of light on leaves, the reflection of light off water, the nature of light at dusk etc. It is these thousands and thousands of Leonardo observations that inspired Isaacson, and ultimately inspire us as his readers, to look at the world a little more closely, a little more carefully, a little more minutely. A little more like Leonardo.

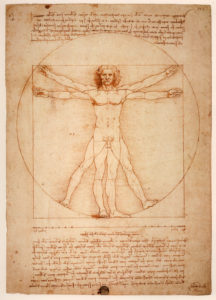

Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man: a small ink drawing illustrating the big idea that proportions of the human body relate to geometric shapes.

In August 2017, the Aspen Institute held a three-day celebration of Leonardo da Vinci. Scientists, writers, and scholars from around the world came to Aspen to discuss various aspects of Leonardo’s accomplishments as Isaacson prepared to launch his new biography. Isaacson was host and impresario, feted and celebrated, since he was stepping down after a long and hugely successful tenure as the head of the Aspen Institute. Leonardo da Vinci was his final contribution to the intellectual life of that vibrant community, but it was also clearly a very personal journey for Isaacson himself. In his final speech which closed the festivities, Isaacson spoke movingly about what he had learned in writing about Leonardo and from Leonardo. He spoke about how he had become more attuned to nature, to the beauties of Aspen, and to the world around him on a daily basis. He spoke of trying to slow down, to listen, to nature, to the birds, to the trees, to the wind. He suddenly began to notice that shadows on the underneath of leaves have a color different from the sunlit surface, that shadows are not black but full of color and are complicated reflections of light and shade … all the things he had been reading for months in Leonardo’s notebooks. Suddenly, Leonardo was not an artist in Florence 500 years ago; he was a person who could make one look, live, learn, and more fully enjoy Aspen, Colorado, today, some 500 years later.

Fittingly, the conclusion to Isaacson’s book has a section entitled “Learning from Leonardo.” Isaacson lists and describes twenty maxims that he gleaned from Leonardo, and that he felt could be relevant to today’s world. I could list them all, but I will not because Isaacson wrote an entire book to justify those maxims. And they make more sense once you have read Leonardo’s biography through the lens of a great contemporary biographer. However, I cannot resist sharing a few, since they are indeed relevant across the centuries. The first is Isaacson’s most important, and something of the leitmotif of his entire volume: “Be curious, relentlessly curious.” My few selections (offered without Isaacson’s descriptive remarks) are primarily intended to pique further curiosity and a desire to read this very good book: “Retain a childlike sense of wonder,” “Think visually,” “Let your reach exceed your grasp,” “Indulge fantasy,” “Be open to mystery,” “Take notes on paper.”

Drawing and writing on paper is seeing one’s mind at work; it is “indulging fantasy,” “being open to mystery,” and “thinking visually” all at the same time. It might even result in a ‘childlike sense of wonder” when something new suddenly emerges—what Isaacson calls Leonardo’s “combinatory creativity”—as an important component of his genius.

That last recommendation—“Take notes on paper”—is more meaningful than at first glance. Isaacson concluded his remarks at Aspen with this same list. When he came to “Take Notes on paper,” he marveled at the fact that he could sit in the Accademia museum in Venice and hold in his hand Leonardo’s drawing of Vitruvian man, and that he could go to Milan, Florence, and Vinci to see original notebooks of Leonardo—turn the pages and see the man at work, sketching out ideas and moving quickly from one topic to another. He lamented that no such paper trail was available to him when he wrote Steve Jobs—a strange lament in the modern world. But, even more than leaving a “paper trail” for posterity, architects, artists and many creative individuals think “out loud” on paper; one sees the last doodle or drawing while moving on to the next; you draw over, erase, combine, add, subtract. Drawing and writing on paper is seeing one’s mind at work; it is “indulging fantasy,” “being open to mystery,” and “thinking visually” all at the same time. It might even result in a ‘childlike sense of wonder” when something new suddenly emerges—what Isaacson calls Leonardo’s “combinatory creativity”—as an important component of his genius. Paper. An old technology recommended to the geniuses of tomorrow.

And so what about that woodpecker’s tongue? It is quite extraordinary! The tongue can extend more than three times the length of the woodpecker’s bill and when not in use, it retracts into the skull and wraps around the bird’s head thereby protecting its brain when the bird smashes its beak repeatedly into tree bark. The force exerted on its head is ten times what would kill a human, but its bizarre tongue and supporting structure acts as a cushion and shields the brain from shock. As Isaacson notes, there is no reason that anyone needs to know this. It has no utility for our everyday, modern life, nor did it have any utility for Leonardo. But, if you read this review, it is hoped you will want to read this book, and if you read this book then you will want to know about the woodpecker and about a thousand other things that interested Leonardo, “just out of curiosity. Pure curiosity” (525).