Eliot Ness: The Rise and Fall of an American Hero & Gunfighter in Gotham: Bat Masterson’s New York City Years

The Lawman came with the sun

There was a job to be done

And so they sent for the badge and the gun

Of the Lawman

The man who rides all alone

And all that he’ll ever own,

Is just a badge and a gun and he’s known

As the Lawman

—Theme song of the ABC series Lawman (1958-1962), a western that copied much of its basic premise from CBS’s Gunsmoke, the latter being not only the longest-running primetime drama in television history and the longest-running western, but the longest-running program about a law enforcement officer.

Social reformation with cops

“Ask consumers of popular culture who came of age in the middle of the twentieth century what the term ‘Prohibition agent’ connotes,” writes Daniel Okrent in Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (2010), “and most will conjure up an image of actor of Robert Stack as Special Agent Eliot Ness, from the 118 episodes of The Untouchables that ran on ABC Television between 1959 and 1963. The real Eliot Ness was named after the novelist George Eliot, had almost nothing to do with the conviction and imprisonment of Al Capone, once ran for mayor of Cleveland (losing by a two-to-one margin), and died a semidrunk (sic) in 1957.” Quite a dismissal of the most famous policeman associated with the enforcement of the Volstead Act, although later in the book Okrent concedes that Ness and the Untouchables “did manage to disrupt the Capone organization’s beer trade for a while.”

Laurence Bergreen, in his biography, Capone: The Man and the Era (1994) suggests that Ness’s parents were unaware that George Eliot was a pen name and thus, I suppose, unaware that the writer was a woman, which seems odd but is possible. Bergreen underscores Okrent’s point “that no matter how many stills Eliot Ness smashed or bootleggers he arrested, nothing he did contributed to the government’s case against Al Capone.” But Bergreen understands why Ness has emerged so inextricably linked to the legendary Scarface, the most famous of all American mobsters: “The gangster controlled a national crime network generating $75 million a year; the honest young Prohibition agent’s annual salary came to just $2,500. Capone was often flamboyant and vicious; Ness was boyish, vague, and hard to read. Capone was fat and dark; Ness stood 6 feet tall and he was rather gangly, with sleepy blue eyes. Capone’s shiny custom-made suits shouted ‘gangster’; Ness dressed conservatively and parted his cornsilk hair in the middle. Capone’s gray eyes and dark hair, not to mention his double scar, gave him an aura of implacable menace; Ness, in contrast, was genuinely handsome, Gary Cooper handsome. Capone raged against his enemies and even took a baseball bat to three of his victims; Ness never lost his temper and always contained his emotions.” Bergreen elaborates on this contrast by advancing that Capone represented what rural Americans, largely the force behind Prohibition, hated about cities, “the crime, the slums, and especially the immigrants.” Ness, “the remedy,” was the fair-haired, All-American boy, Tom Sawyer with a gun. (See the 2003 film The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen to find Tom Sawyer, the law officer and marksman.)

In Ronald D. Humble’s Frank Nitti: The True Story of Chicago’s Notorious Enforcer, a biography of Capone’s second-in-command, Ness is treated in a more balanced way: the Untouchables’ raids were nothing more than “pinpricks against the fringes of the Outfit’s empire.” But Humble quotes crime writer Max Allan Collins asserting that “the tough thing about researching [Ness] is that there has been so much negative post-Untouchables TV show revisionist history—much coming from jealous fellow law-enforcement officers or mob guys wanting to play him down—that it’s hard to know the truth.”

Robert J. Schoenberg in Mr. Capone (1992) concedes that Ness and the Untouchables “cost Capone a lot of money during a crucial period,” while also affirming that the men were true to their name: Capone could not bribe them (a fact that always mystified Capone who did not understand why everyone—gangsters and cops– could not just get along with one another). But Schoenberg downplays the gunplay that is featured in The Untouchables, Ness’s account of his Prohibition years ghostwritten by Oscar Fraley and published in 1957, seven months after Ness’s death. Capone told his boys no rough stuff with the federal officers. He had enough problems without giving the government even more reason to come after him.

During his time busting up Capone’s breweries, Ness, according to Perry, “had an illicit drink almost every evening.” In effect, the rise of Ness was a reformation within the Reformation.

As Douglas Perry informs the reader in Eliot Ness: The Rise and Fall of an American Hero, writing The Untouchables was not Ness’s idea but rather that of his business partner, Joe Phelps. When Phelps and Ness met Oscar Fraley, a journeyman journalist, and Ness, loosened by a few drinks began to tell stories of his Chicago days of busting Capone’s breweries, Phelps hyped the idea of how Ness’s stories would make a good book, not that Fraley needed much convincing to take the bait. At this point, Ness was living in a small town in Pennsylvania. He was broke, absolutely desperate for money, and an alcoholic, (perhaps an irony for a former Prohibition agent but Ness was never opposed to alcohol consumption. He enforced Prohibition because that was his job at the time). Ness was concerned with the liberties that Fraley was taking with the material, making his memoir seem too much like pulp fiction. But Fraley reassured him that the book needed to be spiced up a bit in order to get published. And Ness, after all, needed money because his business plans never worked out. Ness dropped dead in his kitchen from a massive heart attack. Perhaps if he had lived the book would have been different. At any rate, the book angered many people who felt Ness was taking credit, more credit than he deserved or earned, in taking down Capone. The fact that the book generated a successful television series, a 1987 Brian De Palma film, more books, comic books, and more television programs has annoyed many of the families and friends of the people who helped to bring the income tax case against Capone that garnered “Snorky,” as Capone was nicknamed by friends and associates, an 11-year sentence in federal prison. None of this was Ness’s fault, as the book that was published posthumously was not the book that Ness envisioned. Moreover, Ness personally never profited from any of this acclaim and attention. He died penniless before any of it happened. But the anti-Ness legions took their toll of Ness’s reputation. For instance, in Ken Burns’s 2011 documentary on Prohibition, Ness is hardly mentioned. Lynn Novick, co-director of the film, is quoted in Perry’s book as saying that Ness was just a “PR invention.” (She told me as much when I saw her in St. Louis several years ago promoting Burns’s The Tenth Inning, proud of the fact that Ness would not figure at all in Prohibition.)

Eliot Ness offers the thesis that Ness is “one of the most influential and successful lawmen of the twentieth century.” Perrry reminds the reader that Ness was only 30 years old when Capone went to prison, that he was at the beginning of his career and some of his most notable accomplishments were yet to come. He also reminds the reader that when Ness was appointed the public safety director of Cleveland, newspapers there pointed out that Ness had nothing to do with sending Capone to prison. This so-called damning fact was, in fact, common knowledge during Ness’s lifetime and had no deleterious effect on his ambitions. As Perry notes, “work obsessed Eliot Ness,” and in order to wind down from the stress of his work, Ness liked having a good time, dancing, nightclubbing, and drinking. The public’s fascination with Ness was that, especially in the original television series and the film, he seemed so much the heroic Boy Scout. The public’s skepticism of him is that he seemed so much the fallen Boy Scout.

Ness was born in 1902, the youngest of five children, on the South Side of Chicago, a distinct and, in many respects, alien section of the city, “in attitude, in outlook, in experience,” according to Perry. Here were the elements that were to shape Ness: the industrial plants and blast furnaces that dotted the landscape, the saloons and heavy-drinking working men, resentful unionists, and tough, unforgiving neighborhood kids. Ness grew up a Christian Scientist with a strong belief in honesty. He attended the University of Chicago earning a degree in economics. Long interested in investigative work, he wanted to go into law enforcement like his brother-in-law Alexander Jamie, probably the biggest influence of his youth.

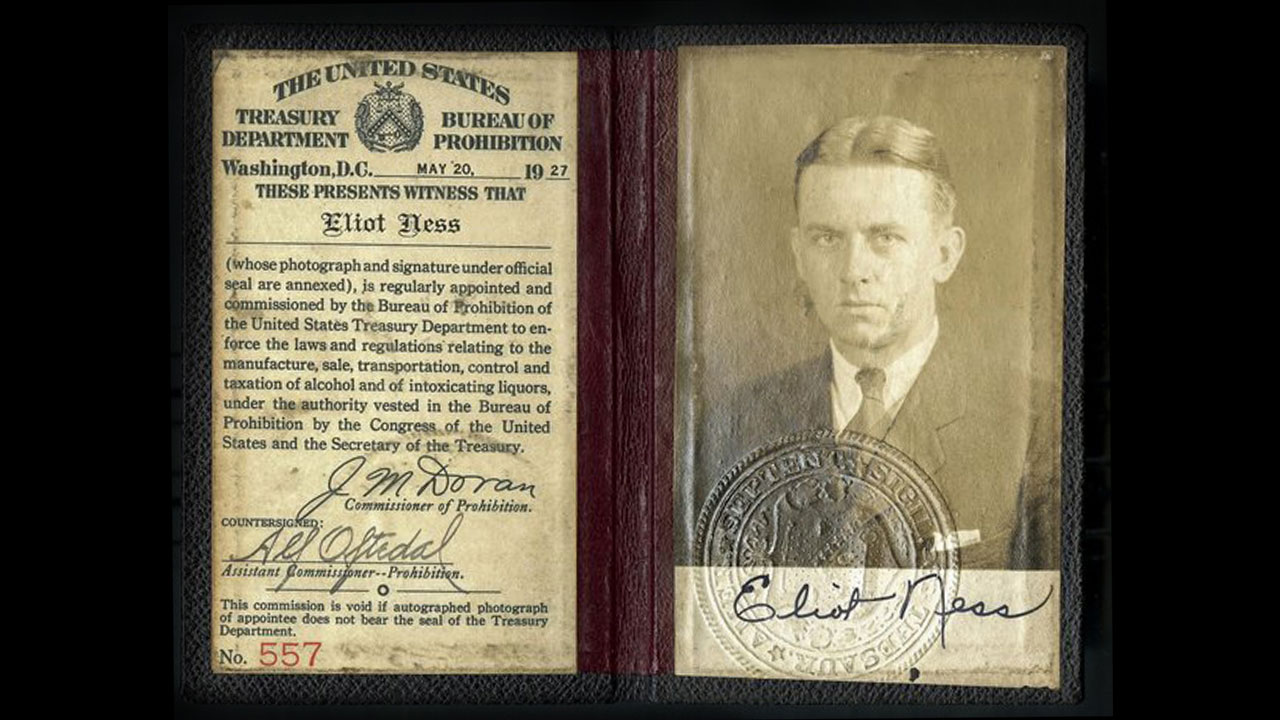

Ness joined the U.S. Treasury Department in 1927 as a special agent in the Bureau of Prohibition in which there was a turnover in personnel. Many of the ideologically committed “drys” were fired, being fervent but ineffective in enforcing the Volstead Act. Men like Ness took their place, uninterested in the morality of drinking, uninspired by any notion of Prohibition as a moral crusade, but very much set afire by the adventure of law enforcement. During his time busting up Capone’s breweries, Ness, according to Perry, “had an illicit drink almost every evening.” In effect, the rise of Ness was a reformation within the Reformation. In order for the massive moral overhauling of American society through Prohibition to take place, as the reformers dreamed, it was necessary for a group of specialist police to make eminent examples of certain people who fragrantly broke the law. Chicago was the place because Prohibition was more notoriously and violently unsuccessful there than just about any other place in the country. Al Capone was the man because—flamboyant, Italian, and decadent—he represented one possible, even plausible future for American cities that was, for the reformers, both morally chaotic and culturally un-American, a blight and a plague of unstoppable corruption. There was a two-pronged plan to get Capone: first, through an income tax investigation and, second, through a steady attack upon his breweries to squeeze his income stream.

To be sure, Ness never reduced Capone’s income by even 5 percent, but he did enough to increase the legal and production costs of doing business and this got Capone’s attention. According to the thinking at Treasury, “there could be no better way to make the Big Fella buck and scream, to make him lose focus on what should matter most to him—being careful. You make a man angry, and he gets sloppy. The U.S. Attorney’s tax case needed Capone to get a little sloppy.” There was very little thought, even at the outset, of bringing charges against Capone for violating the Volstead Act because Treasury was sure he would be acquitted as most of the public simply did not think drinking liquor should be regulated or controlled by the government. The tax matter was a different story. But Ness’s raids were an essential part of the overall plan to bring down Capone. “Snorky” was charged with twenty-two counts of tax evasion and 5,000 violations of the Volstead Act. He was convicted on five counts of tax evasions. The Volstead Act charges were dropped.

Ness believed strongly that science and lab work, not beating confessions from suspects, was the way of the future for police work. Ness also strongly believed in community outreach and encouraged the idea of “the policeman as social worker,” of having the police officer intimately connected to the neighborhood by visiting schools and churches.

Contrary to popular belief and Ness’s assertions in The Untouchables, Ness did not select only young, single men to his squad. In fact, all the men were older than Ness, most were married, and the squad’s personnel was never stable. Agents rotated in and out.

Doubtless, Ness’s most significant job was being appointed Cleveland’s Public Safety Director in 1935 which meant that Ness was in charge of both the police and the fire departments. Because the departments were severely underfunded and undermanned, Ness experimented with how to make the departments work within constraints. Perry credits him with making the modern police department, partly as a result of the influence of his advanced degree in criminology from Chicago which exposed him to radical social-science thinking about how a police department could function. Ness closed stations, abandoned foot patrols (he had too few men to make beats effective), and began increasingly to use patrol cars with two-way radios. The cars were painted odd colors to make them noticeable. He started motorcycle and mounted units. And, most importantly, he invested what funds he had in updating police labs. Ness believed strongly that science and lab work, not beating confessions from suspects, was the way of the future for police work. Ness also strongly believed in community outreach and encouraged the idea of “the policeman as social worker,” of having the police officer intimately connected to the neighborhood by visiting schools and churches. He also believed in redemption, particularly for deviant young people, who ought to be treated with more understanding. “Reporters who covered the police,” Perry writes, “were uniformly impressed with the changes in the department—and they were quick to credit the safety director.”

Ness made enemies, of course, the old guard who would have none of this new-fangled coddling of criminals, those who opposed his crackdown on gambling houses (and the profitable corruption they generated), and the reformers who opposed Ness sweeping out shantytowns. But his undoing was an automobile accident that occurred very early on an icy day in March 1942 with Ness and his second wife returning home from a night of drinking. Ness’s car skidded head-on into the car of twenty-one-year-old Robert Sims. No one was seriously hurt but Ness tried, clumsily, to cover up the accident. When this was exposed, coupled with a scandalous story of young white women having sex with some black entertainers, thus opening Ness to accusations that he did nothing about prostitution in the city, he was forced to resign. He never really found his professional footing again. But his impact on the city of Cleveland was considerable.

East meets west

Bat Masterson1 was good enough friends with Teddy Roosevelt that in January 1904 Roosevelt invited the former lawman to the White House. Roosevelt loved western characters like Masterson, gunfighter sheriffs from frontier towns. After all, Roosevelt lived in the West for a time and felt a certain kinship with its culture. He also shared with Masterson a love of prizefighting, a sport that, despite its unsavory ambiance of gambling and lower-class male camaraderie, illegal status in most of the United States, and general coarseness as a spectacle was enjoying considerable popularity at the turn of the twentieth century. (That Masterson would be associated with boxing as a fan, official, business pursuit, and interpreter is hardly surprising. As boxing historian Nat Fleischer noted, “Gunmen were an important part of the pugilistic picture in those rough-and-ready days, when fair play was best maintained by a judicious display of force on both sides.”)

Bat Masterson, date unknown. (Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photograph Division)

At this meeting, Roosevelt offered Masterson an appointment as a U.S. Marshal for the Western District of Arkansas. Masterson turned down the offer because he did not wish to leave New York City where he had been living since the middle of 1902 and where he would die 19 years later. That is not the reason he gave Roosevelt, however: “My record would prove a never-failing bait to the dime-novel reading youngsters, locoed to distinguish themselves and make a fire-eating reputation, and I’d have to bump ‘em off.” The lawman as gunslinger faces a peculiar danger in a world where refractory punks whose minds have been weakened by bad literature might let fantasy get the better of good sense. In the arena of masculine contest, reputation, legitimate or otherwise, is the thing. I am not sure Masterson actually believed this. Roosevelt probably did.

If anything, Masterson’s myth has endured longer than Ness’s and has been less criticized or debunked, even as the myths about the white or European settlement of the West and the Western as a myth-making art form about “winning” the West have been strenuously challenged.

But Roosevelt did not give up on the idea of appointing Masterson and neither did Masterson, in a back channel sort of way. After the election, in early 1905, Roosevelt offered Masterson as Deputy Marshal of New York, which Masterson accepted at $2,000 a year, a nice salary for the time. This sinecure was the last law enforcement job for Masterson, which he would hold for nearly five years or until Roosevelt’s term ended, his longest tenure as a lawman. Masterson had actually been eager to find a soft job like this since his first visit to New York in 1895 when he served for a time as the bodyguard to George Gould, the son of financier Jay Gould, and wound up spending most of his time on the Gould’s yacht and playing the ponies at Gravesend with Gould’s money. The government, to be sure, offered less money but with no greater demands. (One of the reasons he did not like William Howard Taft, aside from the fact that he was not Roosevelt, was that Taft did not renew the appointment, thinking it a ghastly waste of money. Taft was also not so enamored of western gun-slinging lawmen.)

He never showed up for work except on paydays, and was never given anything to do. The job seemed simply to bestow an honor upon a man Roosevelt admired as “a man’s man,” an emblem of the fortitude and courage of the Western frontier, indeed, bestowing an honor upon a white male myth of conquest and the imposition of order on a wilderness, as it would be characterized by the academic left. Such a characterization as the last clause would not be wrong, but it would not tell us much either. There is something about the appointment that signaled a kind of twilight, the beginning of the end, an acknowledgment of Frederic Jackson Turner’s thesis of the closing of the frontier and the creeping demise of a certain type of man. As Robert K. DeArment says in Gunfighter in Gotham, the appointment never interfered with Masterson’s real day job, writing three columns per week of roughly 1800 words each, mostly on boxing, for the New York Morning Telegraph.

DeArment’s book is something of a complement of his earlier, full-length biography of Masterson, focusing on the final years of Masterson’s life when he lived in New York and began one of the most prolific writers about boxing in the nation, essentially his post-lawman and post-Western years. Masterson, like Eliot Ness, had been distorted by popular culture. In his own day, it was commonly believed because of magazine articles written about him that Masterson had killed twenty-six men, aside from or including a number of Indians in the Battle of Adobe Wells in Texas and while he was an army scout during the Red River War. Under oath while being cross-examined by Benjamin Cardozo in a lawsuit in 1913, Masterson admitted to killing only three men, aside from Native Americans he may have shot in warfare. According to DeArment, Masterson used a firearm against another person only six times in his life outside of Indian fighting.

In the age of movies and television, Masterson was the subject of a television series, portrayed as an on-the-road Western hero, not so far-fetched or romantic as Masterson spent a significant portion of his life as an itinerant faro dealer: Bat Masterson, starring Gene Barry, ran from 1958 to 1961, overlapping with the broadcast of The Untouchables. He was a secondary character in another show of the period, The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp that aired from 1955 to 1961. The Masterson character has also been featured in several Wyatt Earp feature films. His association with Earp, probably the most famous western lawman in American history, especially working with Earp as “special policemen” in Dodge City, Kansas, crystalized Masterson’s image of being both a lawman and a gunfighter. At twenty-three, Masterson was elected marshal of Ford County which included Dodge City and he followed Earp to Tombstone, Arizona. If anything, Masterson’s myth has endured longer than Ness’s and has been less criticized or debunked, even as the myths about the white or European settlement of the West and the Western as a myth-making art form about “winning” the West have been strenuously challenged.

There are two observations to make about DeArment’s account of Masterson’s post-lawman years: First, Masterson’s connections with boxing as a manager and promoter as well as his saloon ownership and gambling made him, in the parlance of the time, a sport, someone who made his living connected with socially disreputable activities. As a frontier lawman, Masterson, like most policemen, would have known the sporting world, the world of fringe and underground economies, very well. It is a commonplace observation that there is a thin line between law enforcement and the criminal classes seeking “suckers” among the socially respectable. Reformers have always wanted to eradicate the underground; the police, in merely containing it, have found it a good source of income and power. (Capone, much to his annoyance, felt he was buying nearly every cop and politician in Chicago in order to make and distribute his liquor. To his glee, of course, he learned that they could be bought. It was the reformers, basically, moralists, the Prohibitionist ideologues, who wanted to get rid of him, not the law enforcement establishment or the customary political order it serves.) Ironically, Masterson’s desire to regulate and legitimize boxing was, essentially, a reformer’s impulse, a realist reformer, to make boxing respectable against the wishes of the totalizing moralist reformers who wanted to ban it entirely.

It is a commonplace observation that there is a thin line between law enforcement and the criminal classes seeking “suckers” among the socially respectable. Reformers have always wanted to eradicate the underground; the police, in merely containing it, have found it a good source of income and power.

Second, Masterson’s conflicting impulses were clearly shown in his politics. He was a rabid fan of Roosevelt and the Progressive wing of the Republican Party yet he bitterly opposed such reformist jewels as the Sullivan Law which banned concealed handguns or having handguns in the home or business, and women’s suffrage, which he said would not improve the quality of government or elections as its proponents claimed. He felt gun laws denied people their individual freedom. He wanted boxing to be highly regulated in order to make it a true sport and not just a confidence game where fixed fights ripped off the public and rowdy crowds kept away the socially respectable. But on the whole, Masterson was opposed to regulations as a way of improving people and improving society. This was partly his instinct as a Westerner who was used to living on a frontier which was generally less regulated, where people had to forge their own way; and partly it was his instinct as a lawman who understood the moral foibles of people and generally was not offended by them. The fact that he thought controversial black heavyweight champion Jack Johnson had been railroaded in his Mann Act trial (the Mann Act, which made prostitution a federal offense, was another moral reformist legislative jewel) and that Masterson campaigned to obtain Johnson a pardon, although he had no greater tolerance of miscegenation in the form of black men having sex with white women than any other white man of the period, illustrates this inherent complexity in Masterson’s social and political views, influenced by his having been a policeman and his having been inextricably bound to the underground economy.

What these biographies of Ness and Masterson reveal is that police work is not so simple and straight-forward—cops versus robbers, order versus chaos—as many might think, and clearly the people who do such work are more complicated in their impulses and motivations, more conflicted or contradictory as human beings about the meaning of what they are doing, than partisans of either side of the political spectrum are willing to concede. The police are a very flawed sort of superego. Policing is tied to morals and to heroism in ways that reflect society’s unconscious desires about both regulation and temptation, about control and desire. The lawman is our collective hope for a potent masculinity that protects us by confronting danger, solving all mysteries (both Ness and Masterson considered themselves master investigators), and clearly identifying the evil in transgression. The lawman is also our collective fear of a misguided, rampaging masculinity that operates arbitrarily and crudely, obscures and protects corruption, and fails to understand that transgression is sometimes a necessity or a token of a larger evil. We ourselves as a society are confused in wanting to absolve the lawman while wanting to implicate him. As a reflection of our own imperfection, whether we deserve him as our fate and as our myth, the lawman as he is so precariously constituted, is, at best, an uncertain form of social correction. And as with everything else in this life, we must learn to live with uncertainty.