But the job [of First Lady] remains undefined, frequently misunderstood, and subject to political attacks far nastier in some ways than those any President has ever faced. It has complications as mind-boggling from a psychological or political point of view as the conundrums faced by the docile-domes in the State Department or the Pentagon. For one thing, almost all the people in Washington, D.C., are there because they want to be at the white-hot center of power. The ones with the most power, members of Congress and the President, have the added assurance that the American people have sent them there. That is particularly true of the President, the one politician who is elected by the vote of the entire nation. . . . On the other hand, a First Lady, as Lady Bird Johnson has noted in her gentle southern way, has been chosen by only one man—the President—and it is highly unlikely that he was thinking about her as First Lady when he proposed. No matter how different our First Ladies have been . . . they have all shared the unnerving experience of facing a job they did not choose.

—Margaret Truman (daughter of Bess and Harry Truman), First Ladies: An Intimate Group Portrait of White House Wives, (Random House, 1995)

I. The Wife as Vice President

Her self-discipline, I think, began with the decision to do what her husband needed, to accept the demands made on her, and to find in them not irritation nor disruption of her own inner life but instead its very purpose. This is neither easy nor impossible—it is simply hard. I believe that Bird Johnson’s astonishing energy and strength of character stem from an old decision to forget about herself.

—Elizabeth Janeway on Lady Bird Johnson

Lady Bird Johnson, wife of Lyndon Baines Johnson, who succeeded John F. Kennedy (1961-1963) as president and preceded Richard M. Nixon (1969-1974), had tough acts to follow. Eleanor Roosevelt, the most important First Lady of the twentieth century, if only because she held the position longer than anyone else (1933-1945), was certainly the model for First Lady social engagement. And Jackie Kennedy, Lady Bird’s immediate predecessor, who sat next to John as his brains were blown out on a public street in Dallas, managed to lead the nation during the days that followed with unimaginable grace and dignity. Without question, Jackie was the most glamorous First Lady we ever had and the only one since Ellen Folsom, wife of Grover Cleveland (1893-1897, 1885-1889) still giving birth while First Lady. She was also a powerful mythmaker as the architect of the Kennedy White House as Camelot.

So, Lady Bird had to follow the Committed Activist and the Courageous Widow. Subsequently, such First Ladies as Hillary Clinton, the most politically ambitious and accomplished, and Michelle Obama, the first African American First Lady, which made her indelible and path-breaking if she had never uttered a word, submerged Lady Bird. Also, Lyndon Johnson’s presidency was defined by the tragedy of the Vietnam War—the failure of American military power and the overweening claims of American exceptionalism—and the triumph of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the fundamental racial transformation of our country. Johnson’s term was the time of urban race rebellions, the civil rights movement, political assassinations, rock music, the sexual revolution, and the popularization of illegal drugs. Lady Bird does not seem to figure in much of this as a significant historical voice or actor. Just another First Lady, at first blush.

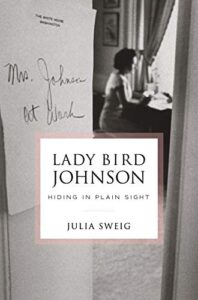

Julia Sweig’s richly researched, extraordinarily detailed biography of Lady Bird’s term as First Lady is a substantial attempt to bring needed and deserved attention to the woman who was essential to Lyndon’s self-understanding and his ambition. “[W]hat most all historians and journalists miss in writing about Lyndon Johnson. . . is the weight of Lady Bird’s influence within their marriage and on the LBJ presidency.” (xxii) It was Lady Bird, for instance, who convinced Johnson to run for election in 1964, after he had assumed the presidency as a result of Kennedy’s assassination the previous year. He was unsure if he wanted to. He did not think he would lose and winning an election would make his presidency legitimate, although of course there would be many who thought that Johnson would win only because of Kennedy’s death, not because of any particular virtues he offered as a politician. But he greatly feared that Vietnam was a trap from which he could not escape: “the wrong war at the wrong time in the wrong place with the wrong enemy,” to borrow Omar Bradley’s observation about the Korean War. He feared a bad outcome in Vietnam even before he began to escalate significantly the American military presence there. South Vietnam was not a side in a conflict but a figment of the militant anti-communists’ imagination, a political mirage ever receding over the horizon that no amount of American cash could make real. Moreover, many of his Texas friends and cronies felt he had betrayed them when he accepted the vice-presidential slot on Kennedy’s ticket. They would feel even more betrayed by his push for civil rights. As Sweig writes, “Ambivalence, the prospect of loss, the suggestion of illegitimacy—these were the constant themes in Lyndon Johnson’s career.” (6)

Johnson’s term was the time of urban race rebellions, the civil rights movement, political assassinations, rock music, the sexual revolution, and the popularization of illegal drugs. Lady Bird does not seem to figure in much of this as a significant historical voice or actor. Just another First Lady, at first blush.

Lady Bird wrote a precise memo laying out the pros and cons of running but ultimately endorsing the run in 1964. Johnson ran, indeed, with considerable energy and cunning, wanting to massacre Republican Barry Goldwater by all means fair and foul (and foul especially as so many right-wingers have thought and written), which he did, winning 61 percent of the vote. Sweig claims that all LBJ historians and biographers know about the memo but hardly any acknowledge its importance in persuading the president, even though Lyndon himself did so in his autobiography. (xxii-xxiii) Hence, the title of this biography, Hiding in Plain Sight.

It should also be remembered that Johnson did not select a vice president until the 1964 Democratic convention in August. There had been no vice president from November 1963 until then, nine months. Actually, Lady Bird was, in effect, the vice president. She was clearly operating very often as if she were. Even the press noticed this. (72) Chief White House usher J. B. West put it this way in his memoir: “And I did not run the White House. Lady Bird Johnson did—and in a way no other First Lady had done. She was rather like the chairman of the board of a large corporation.” (39) Considering Lyndon’s enormous insecurities, he probably felt that for the first several months of his presidency no one could serve him better than Lady Bird. He could trust her unconditionally. There was no politician, no matter how chummy they were, he could trust in a similar way. (As he was to find out, for instance, when his mentor, segregationist Senator Richard Russell of Georgia, broke from him over the issue of civil rights and Senator William Fulbright of Arkansas over Vietnam. In politics, no one is more untrustworthy than one’s friends and allies!)

She was a professional wife, and a professional’s wife, but also a successful businesswoman, as well as the woman in charge who served as a bridge for the rise of professional women who did not live either through or for men. Perhaps this is why First Lady historian Margaret Truman called her “the almost perfect First Lady.” This is the burden of Sweig’s mammoth biography, proving this crucial point.

Lady Bird privately noted that the presidency required two people. And she called it “our presidency.” (72) Shades of Hillary Clinton who thought the election of her husband was giving the public two for the price of one. It is no wonder that in Barbara Garson’s 1968 anti-LBJ satirical play, MacBird!, she cast Lady Bird as the manipulative, power-driven Lady Macbeth. How important was Lady Bird? Consider the title of the play. But she was nobody’s Lady Macbeth, nor a caricature of the scheming wifey behind the throne, nor the suppressed ego of the modern White bourgeois marriage as described in Betty Freidan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963), a book that Lady Bird, an avid reader, almost certainly read. She promoted the cause of women more than any First Lady who preceded her with the possible exception of Eleanor Roosevelt. Indeed, Eleanor was her model. Lady Bird was a New Deal young adult, was greeted and tutored by Eleanor when she first arrived in Washington in 1937 as the wife of Texas Congressman Lyndon. She lived for and through Lyndon, to be sure, by her own admission but, in this way, she became her own person, with her own agenda. She was a professional wife, and a professional’s wife, but also a successful businesswoman, as well as the woman in charge who served as a bridge for the rise of professional women who did not live either through or for men. Perhaps this is why First Lady historian Margaret Truman called her “the almost perfect First Lady.” This is the burden of Sweig’s mammoth biography, proving this crucial point.

II. The New Southern Woman

Claudia Alta Taylor was born on December 22, 1912 in Karnack, Texas to a prosperous family, the youngest of three children. The Black women who reared her gave her the pet name Lady Bird. It stuck. Her mother, who died when Lady Bird was five, had been an avid reader and supported women’s right to vote. Lady Bird graduated from the University of Texas in Austin in 1934 with degrees in history and journalism. She thought her ticket for leaving Karnack would be her own yen to travel and see the world. She imagined herself a working journalist. It wound up being Lyndon Johnson, an ambitious political staffer, who wanted to marry her as soon as he saw her. Through Lyndon’s political career she got to see most of the United States and a significant portion of the rest of the world, and meet many of the most important people of her time, more than even the most renowned journalist.

When Lady Bird became First Lady, she was hardly a southern provincial or a back-country hick. (Popular sitcoms of the 1960s—The Andy Griffith Show, The Beverly Hillbillies, Petticoat Junction, and Green Acres—offered various takes of the small-town White southerner, from wise to innocent to dumb.) If anything, she represented a New South, cosmopolitan, supporter of New Deal liberalism, and supportive of civil rights for Blacks. She wanted the South to negotiate inevitable change maturely but also to know that she empathized with the White South. As she said during the 1964 campaign, when the passage of the Civil Rights Act was the biggest thing in American politics at the moment:

“I know the Civil Rights Act was right, and I don’t mind saying so. But I’m tired of people making the South the whipping boy of the Democratic Party. There are plenty of people who make snide jokes about the cornpone and the redneck. I’m no hard-sell person. But what I want to say to those people is that I love the South. I’m proud of the South. I know there have been great achievements there.” (115)

Her disapproval of snobbish northern White liberals looking down their noses at the backward South is understandable, especially as the North was not entitled to any prizes for model race relations. She campaigned in the southern states most critical of LBJ’s civil rights initiative during the 1964 campaign—she asked for the difficult, unfriendly locations—and Lyndon credits her with his being able to hold his own against Goldwater in the South. She made forty-seven stops in eight states and met her share of disgruntled, hostile White southerners. (When Johnson began his push for civil rights, Lady Bird focused on the plight of poor Whites, probably understanding that they would be the most resentful.)

If she had hoped that the New South would be Martin Luther King, Jr. lying side-by-side with John C. Calhoun or the Confederacy with the Civil Rights Movement, then, according to our current age, she hoped for too much. The White South was and is destined to pay a steeper price for the loss of its privilege. On the other hand, the pressure of the activists was critical for the passage of the monumental civil rights laws of the 1960s but not without the aid of a president willing to press hard to get them through Congress. It was necessary to have not simply a southern president but a southern couple in the White House. The situation paralleled the politics of the year immediately following the assassination of Lincoln. Radical Republicans were able to pass legislation that far exceeded anything Lincoln himself could have done and probably would have done. Johnson, as a White southerner waving the bloody shirt of JFK, could pass more radical legislation than Kennedy could have or would have wanted to. Johnson realigned American politics. The Democratic Party became the party of new, mandated rights, the safe haven party for Blacks, the party of the massive welfare state. Only a White southern couple could have exploited Kennedy’s death so thoroughly in this way.

But the opposite was true too. Johnson felt that, as a southerner, he could never truly unite the country. His failure to unite the country was the downfall of his presidency and he felt keenly that the eastern establishment went out of its way to deride “my style, my clothes, my manner, my accent, and my family.” (103) Being White southerners made it possible for the Johnsons to do certain political things but also made him highly vulnerable culturally. The South, for the North, was still the American Gothic or the American Grotesque. The New South was never quite new enough for the eastern elites.

The Democratic Party became the party of new, mandated rights, the safe haven party for Blacks, the party of the massive welfare state. Only a White southern couple could have exploited Kennedy’s death so thoroughly in this way.

Lady Bird had lived in Washington for several years, the highly visible and influential wife of a powerful congressman, the Senate majority leader. She had also been the wife of a vice president. She knew and got along well with Jackie Kennedy. Indeed, as the vice president’s wife, she often substituted for Jackie at major events and functions as Jackie battled miscarriages. Lady Bird understood and even admired Jackie’s glamor and, wisely, never tried to compete. Margaret Truman writes, interviewing Lady Bird on the same day that Jackie Kennedy died, how “Lady Bird spoke in almost biblical cadences about how much she had come to love and admire Jackie for her bravery, her grace, her generosity of spirit.” Two days after JFK’s funeral, Jackie had tea with Lady Bird at the White House. “Don’t be frightened,” Jackie said, “Some of the happiest years of my marriage were spent here—you will be happy here.” She said it six times. Lady Bird was stunned that Jackie was upright and rational, or seemingly so. Lady Bird’s immediate concern after JFK’s death was the balancing act of trying to honor Jackie’s wishes (Jackie sent Lady Bird an eight-page letter outlining them), the best interests of a very new Johnson presidency, and her own personal ambition. (36) It was no easy task. A huge part of Lady Bird’s success was her ability to handle her relationship with Jackie the Widow so well. Only a political pro and a woman of some considerable personal skill could have done it. But the contrast between her and Jackie worked ultimately in Lady Bird’s favor, the gentle southern woman who could seem like Melanie but had the brains of Scarlet.

III. “ . . . the problem of dwindling beauty” (187)

Lyndon stretches you.

—Lady Bird Johnson

As Sweig writes, “[Lady Bird] professionalized the office of the First Lady with a chief of staff and press secretary, a social secretary, and their own staffs.” (111) The office today is Lady Bird’s creation. She made the East Wing a force. She cultivated, even empowered, the women press corps that covered her. But she was skeptical of the idea of women as a voting bloc. She thought women were simply too diverse a group to have a common political identity. Nor was she convinced that they should.

She also did something hardly any other American politician had achieved: she made the word “beauty” a part of the language of public policy. Perhaps there is a certain irony in thinking of the 1960s as the era of “beautification” as it was also the era of the “Ugly American,” intensified particularly by the Vietnam War. (The 1958 novel, The Ugly American by Eugene Burdick and William J. Lederer, was about American diplomatic incompetence in a fictional Southeast Asian country.) Some dismissed this as a female concern, trivial compared to the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, our relationship with the Soviet Union, and the like. But it was an aspect of the civil rights movement—let us say, the perverse twin of the civil rights movement, the violent urban rebellions—that spurred the beautification movement, the decline of American cities, which was far from a trivial issue and would become a crisis in the 1970s.

The office today is Lady Bird’s creation. She made the East Wing a force. She cultivated, even empowered, the women press corps that covered her. But she was skeptical of the idea of women as a voting bloc.

What in part caused the riots was police brutality but far more important in many respects was the policy of urban renewal that the United States embarked upon after World War II. Major cities cleared slums, displacing thousands of people, many of them Black and poor or working class. Either high-rise concrete towers were built to house the displaced, architectural and communal disasters, or nothing at all was done for them. In this way, cities became more unlivable for Blacks than ever. It might seem that Blacks needed more than “beauty” but the whole point of Lady Bird’s program was that people cannot live fulfilling lives if they are surrounded by ugliness; it reminds them constantly of what the society they live in thinks they are worth. It also means that people living in such conditions must put so much more effort into creating the beautiful for themselves and that they are always fixated on escape of one sort or another. It is impossible to have a true community based on the idea of escape. The beautification program was a precursor to environmentalism; and as one of Lady Bird’s projects was the beautification of a Black section of Washington, it made aesthetics and Black communal life a public policy concern. This was no small matter: federal highways were the biggest wrecker of neighborhoods, one of the worst blights on the landscape that our country had. The one activity that united urban Blacks and Whites in the 1960s, which Lady Bird noted, was fighting the construction of highways through their neighborhoods. (In Philadelphia, my hometown, Blacks and Whites of South Philadelphia in the 1960s got together to stop the construction of the Crosstown Expressway. Poor and working-class though we were, we loved what we had and did not trust the city and federal governments’ promise of better things.)

Sweig devotes a chapter to the Eartha Kitt/Lady Bird dustup on January 18, 1969. Kitt, a dancer/singer/actress who, by the 1960s, had built a considerable audience both in the United States and abroad, was invited to a Doers Luncheon, a series featuring prominent professional women that Lady Bird had started on becoming First Lady. She had not held any such luncheons in 1967. Criticism of LBJ’s war policy was making the White House an increasingly isolated place. As early as 1965, the intellectual and artistic elites began turning on the Johnsons because of Vietnam. Lady Bird’s White House Arts Festival that year was boycotted by noted writers such as poet Robert Lowell while others used their appearance to signal their displeasure such as writers John Hershey and Dwight Macdonald. By 1967, Lady Bird was finding it difficult to speak on college campuses because of the outpouring of protesters, the petitions by students and faculty wanting her disinvited. She could not speak on something other than Vietnam without being confronted with the subject. She could not speak about Vietnam without being attacked. Restarting the Doers Luncheons at least protected Lady Bird within the White House with a selected audience. Or she may have thought.

The subject of the January 18 gathering was “Crime in the Streets.” Fifty important, accomplished women attended including Kitt who was invited because of her work to support psychiatric services and prevent juvenile delinquency among young Blacks. Kitt came with an attitude and an agenda. First, she confronted LBJ as he was leaving the meeting after making some brief remarks, asking him about what the government could do to help working mothers get affordable childcare. Lyndon was unflappable, accustomed as he was to disgruntled people with tough, challenging questions. He answered her and left. Later in the meeting, Lady Bird, feeling Kitt seething as others made remarks, recognized the actress’s raised hand. Kitt then gave a rambling, garbled intervention essentially arguing that the war was causing juvenile delinquency, that by drafting young men and sending them to fight and die in a meaningless war was tantamount to disrespecting their right to live and so why should they respect a country, a government, a society that would permit this. Despite the jumbled nature of her soliloquy, her point was trenchant, probably better even than she knew. Her statement was not unanswerable but it was a challenge.

By 1967, Lady Bird was finding it difficult to speak on college campuses because of the outpouring of protesters, the petitions by students and faculty wanting her disinvited. She could not speak on something other than Vietnam without being confronted with the subject. She could not speak about Vietnam without being attacked.

There are two things that Sweig’s account of this makes clear: Kitt did not spit at Lady Bird. (Margaret Truman reported that some accounts said Kitt did.) And Lady Bird did not cry in giving her response, although Kitt clearly unnerved her. Lady Bird may have been feeling particularly vulnerable and frustrated because of the tremendous opposition the war had generated; and she may have been annoyed by what she probably considered Kitt’s grandstanding. Lady Bird did what she needed to do: win over her audience and save her event from being capsized by her husband’s critics. It was an effective answer, made more so because it was heartfelt, but it was not an actual or, shall we say, a real answer. What happened after was basically a White House smear job. The press demonized Kitt; the CIA and the FBI opened files on her, and her job opportunities in the States dried up. It seems, in retrospect, a petulant overreaction, all the worse for the Johnsons because of the racial overtones of the encounter, although neither Kitt nor Lady Bird ever explicitly mentioned Blacks in their remarks. Lady Bird learned that it is hard to be a White friend to Negroes, who, in the end, seem only to want more of what they want. What else can you want, for what else do you know but what you want? But this should have not surprised her. For what else is politics but the fight for the power to make your cravings matter?

IV. 1968

Just two weeks after the Eartha Kitt incident at the White House, the North Vietnamese launched the Tet Offensive, an all-out attack on over 100 cities and towns in South Vietnam, a communist blitzkrieg to win the war. The United States beat back the Tet Offensive; we won militarily but it was the decisive battle that made Americans realize we could not win the war. It is funny how war works: you can win an important battle decisively while hopelessly losing a war. On March 31, LBJ announced he would not run for re-election, something that Lady Bird had been hoping for and gently advising him to do since 1965. She sat in the Oval Office, off camera, as he gave the speech, reminding him as she always did before his major addresses, “Remember—pacing and drama.” She had studied public speaking in school and was much better at it than her husband. She never thought public speaking was his strong suit. And just like that, it was over for Lady Bird and Lyndon, although it was only the end of the beginning of the agony for the Democratic Party and for our nation as a whole.