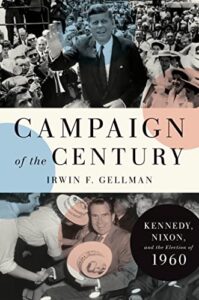

Irwin F. Gellman wanted to describe and analyze the 1960 presidential campaign, “the campaign of the century.” He particularly wished to set the record straight about the Republican, Richard M. Nixon. To Gellman, Nixon deserved higher marks for the operation and substance of his campaign. He sees Kennedy as more expedient as well as superficially more attractive. However, somehow, this volume does not capture the excitement of a very close contest nor how each candidate tried to increase his support. Relying on the archived papers of a goodly number of participants and on newspaper clippings, Gellman has “The who, what, and where” but misses the why. Also, he accepts the truth of these sources while disparaging those of earlier writers.

It could be said that the Kennedy-Nixon contest was a transitional one. Certain factors such as negative campaigning on television had not evolved and the social media had not yet been born. The phenomenon of “pack journalism” did exist. There were boundaries to which reporters adhered. Investigative journalism would have to wait until the denouement of the Nixon presidency fourteen years later. Political bosses could still deliver votes. But money raising did not reach the levels of later years and PACs did not exist. Whistlestop campaigning was still commonplace and media markets were not as important in scheduling appearances.

Gellman describes the candidates well. Kennedy embodied youth. He was attractive and charismatic to some. His speaking style was crisp and action-oriented. Ha also had an attractive family that campaigned for him and a father with deep pockets. Nixon did not grow up amidst wealth. Although bright, he came across as more awkward and not as good looking. As young senators, they had a cordial if not particularly close relationship.

It could be said that the Kennedy-Nixon contest was a transitional one. Certain factors such as negative campaigning on television had not evolved and the social media had not yet been born. The phenomenon of “pack journalism” did exist.

Gellman’s view of Nixon’s campaign history raises some questions for this reader. He denies that Nixon portrayed his 1946 House opponent and his 1950 Senate opponent as being soft on communism. Previous studies conflict with Gellman’s premise. For example, Logevall (435) found that Nixon in his 1946 race for the House was “falsely accusing his Democratic opponent … of being a Communist, or at least of working with a political action committee that was infiltrated by Communists.” Nixon won and joined the House Un-American Activities Committee. He was instrumental in establishing that Alger Hiss had given information to the Soviets.

Gellman states that Nixon never called his 1950 Senate opponent a “pink lady.” Oshinsky’s thorough study of McCarthyism cites Nixon saying he was “bringing the red danger . . . to the attention of the voters.” (141) And he did succeed in his campaign against Helen Gahagan Douglas, a New Deal liberal and civil libertarian, in doing just that. According to Oshinsky (177), “Nixon began by calling her ‘an ex-movie actress with ultra-radical leanings.’” Oshinsky (177) continued that Nixon said that Douglas “had consciously fought to prevent the exposure and control of Communism in the country.”

When Dwight Eisenhower selected Senator Nixon as his running mate, he “wanted above all a vice-presidential candidate with a demonstrable record of anti-Communism.” (Hitchcock, 72) Nixon had that.

Gellman maintains that Ike strongly supported his vice president to succeed him. Eisenhower’s recent biographer, William Hitchcock, would demur. To him, Eisenhower cared more about his legacy than Nixon per se in 1960. He “never believed in Nixon and did not particularly like him.” (Hitchcock, 495)

The norms of reporting were far more staid sixty-two years ago and the truth of these matters was not revealed until well after Kennedy’s assassination. How many Americans in the 1930s knew Roosevelt could not walk?

Kennedy’s Catholicism was an undercurrent in the campaign. Gellman carefully notes various voter comments embodying an anti-papist bias. How influential this bias was is hard to ascertain. Gellman does not cite polling questions nor confidence intervals. Statistics on which group supported either candidate is also opaque.

While the movement for Black equality grew, civil rights did not figure in the campaign. Nixon’s record in this area was stronger than Kennedy’s. Gellman postulates that Kennedy did not wish to alienate powerful southern Democratic committee chairs. Yet, when an advisor suggested Kennedy call Mrs. King after her husband’s arrest to show concern for his security, Kennedy did so with alacrity. Nixon did nothing. In fact, he did not mention civil rights at all in the campaign. Gellman never makes clear how only a small proportion of Blacks in the south were able to cast a ballot in 1960.

His treatment of the debates is thorough. He also relates evidence of voter fraud in Chicago and Texas in considerable detail. If one needs a more favorable opinion of Nixon, it can be found in his decision not to contest the election.

Gellman’s depiction of John Kennedy and his campaign does not raise any red flags. He describes the campaigning, the advisors and the family in a manner akin to other accounts. He is critical of reporters and others for not revealing Kennedy’s chronic womanizing or the true nature of his health. The norms of reporting were far more staid sixty-two years ago and the truth of these matters was not revealed until well after Kennedy’s assassination. How many Americans in the 1930s knew Roosevelt could not walk?

The 1960 presidential election was a close contest. Often, only two points separated the candidates in opinion polls. Yet, Gellman’s account is often dull. One learns where campaigning occurred on a given day and a brief summary of the stump speech. There are two areas that Gellman handles well however. His treatment of the debates is thorough. He also relates evidence of voter fraud in Chicago and Texas in considerable detail. If one needs a more favorable opinion of Nixon, it can be found in his decision not to contest the election. He put national interest first. Gellman could have played this up. His book can serve as a reference but not a complete guide.