The 1640s were the great age of English revolutions, the high point of radical hopes for political change, for freedom of the press, for the liberation of the conscience, even, for some, freedom from the thralldom of marriage. In the midst of this revolutionary clamor—and the number of print publications in this decade of revolution was tremendous—a distinctive voice could be heard within the din of revolution, the voice of John Milton, poet, prophet, and political dreamer. Some of Milton’s revolutionary writings would prove long lasting indeed, but Milton the revolutionary was slow in the coming and when he got there, he seemed to have arrived with mixed motives. The aim of this essay is twofold, first to explore the nature of Milton’s revolutionary impulses and ambitions, and especially in relation to divorce, and then to wonder at Milton’s rhetoric and his sense of selfhood in the revolutionary ferment of the 1640s.

In the life that we know best of John Milton, the life of the poet, the opening moves of his career seem quite conventional, indeed conservative. He developed his skills in the most traditional genres: sonnets in English and Italian, songs and adaptations of psalms, pastorals, epitaphs, elegies, and masques, the latter deeply associated with aristocratic display, with the power and charisma of the court and its mixture of theatrical modes: dance, costume, music, and poetry. Comus, Milton’s ‘masque’ for the earl of Bridgewater, was performed in 1634 at Ludlow Castle, first printed in 1637, and then given a new, revised life in 1645. In literary matters, Milton was no revolutionary at all, even so late as 1645 when, in the midst of religious radicalism and civil war, he fashioned his literary debut with The Poems of Mr. John Milton . . . the songs set to music by Mr. Henry Laws, Gentleman of the King’s Chapel and of his Majesty’s Private Music; hardly a rebellious act or a manifesto for change.

The mixtures and contradictions of Milton’s print record—an elegant and aristocratic volume of verse, an icon-breaking blast at the martyr king—point to a writer who in the decade of revolutions maintained an aristocratic cultural identity but stood ready to man the barricades on behalf of the new: to denounce the tyranny of the established church and to campaign for divorce, the latter an outrageous advocacy, though Milton claimed, in arguing for divorce, that he wished only to return to first principles as they were to be found in Scripture.

And yet, The Poems of Mr. John Milton was published near the time of Milton’s scandalous divorce tracts (1643-5), his anti-prelatical writing, his bold treatise on education (1644), his revolutionary call for an end to pre-publication censorship (1644), and in the same decade as his outrageous—outrageous at least to royalists and loyalists—blast against the blessed memory of Charles I. That pious king, tried and executed by the parliamentary regime in 1649, had written—or so his PR office claimed—a most elevated collection of narratives and prayers wherein the diabolical origins of the civil war were detected and the purity of the king’s motives and elevation of his spirit proclaimed. The king’s Eikon Basilike (1649) was a startling best-seller; it ran through an unprecedented 49 editions in the year of its publication. The new government of parliamentary victors could not let this polemical triumph stand, so they hired John Milton to answer the late king, point by point, chapter by chapter, prayer by prayer, to demolish every plank on which the Eikon Basilike stood. Perhaps 100,000 copies of the king’s book were in circulation by the end of 1649; in that same year John Milton’s Eikonoklastes (‘image destroyer’) was published in one edition—perhaps 1000 copies were in circulation that year.

The mixtures and contradictions of Milton’s print record—an elegant and aristocratic volume of verse, an icon-breaking blast at the martyr king—point to a writer who in the decade of revolutions maintained an aristocratic cultural identity but stood ready to man the barricades on behalf of the new: to denounce the tyranny of the established church and to campaign for divorce, the latter an outrageous advocacy, though Milton claimed, in arguing for divorce, that he wished only to return to first principles as they were to be found in Scripture. I do not intend to resolve or to explain away the contradictions between Milton’s conservative poetics and his revolutionary politics, but rather to ask what might explain his turn to revolution and how his revolutionary writings reveal at once Milton’s elevated ideals and his self-regard and self-imagining as well as the angers and disappointments that drove him to proclaim revolution in what would come to be called the public sphere as well as in the private domain of the family.

In the decade of revolutions

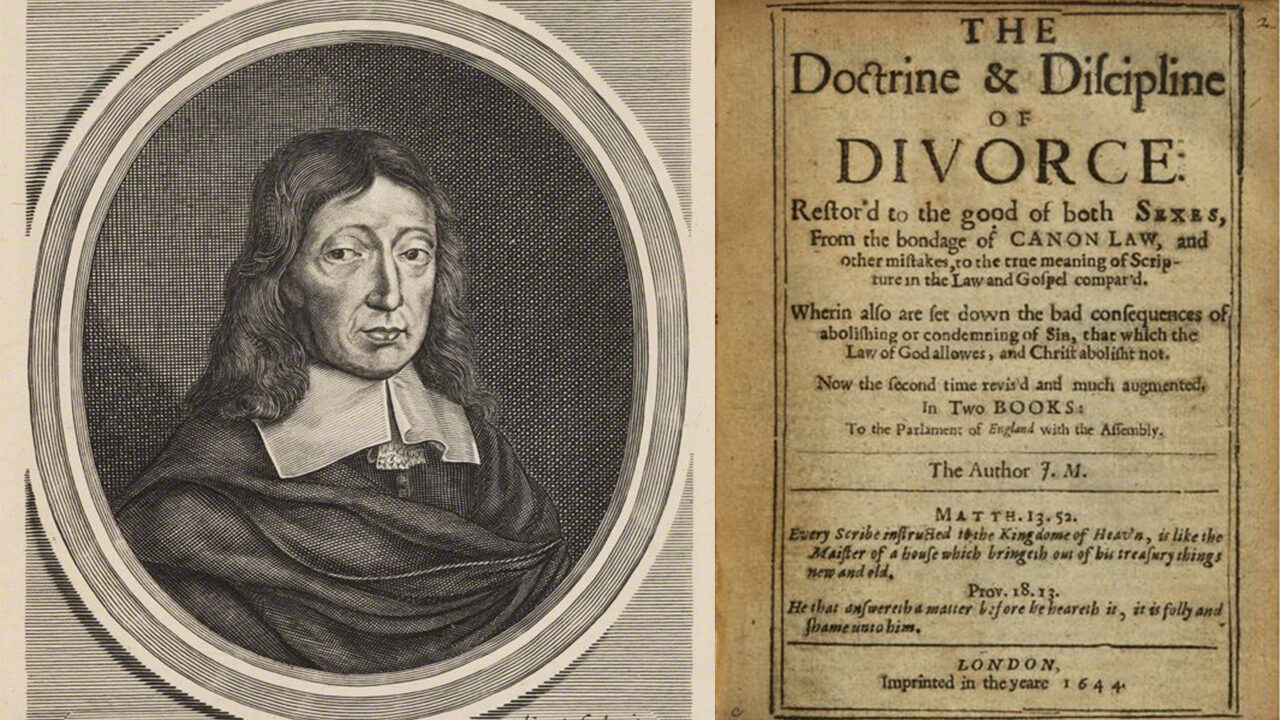

Not surprisingly, it is the “domestic species” of liberty—the domain of the family—that presents the most striking mixtures of public ideals and personal motives. Here is Milton in a flight of lofty public advocacy, staking claims in The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce (1643) on behalf of human freedom and autonomy; here is a man driven by the call of public duty to denounce the “needless thraldom” of marriage and to raise “many helpless Christians from the depth of [marital] sadness and distress.” It is also true that the Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce speaks the language of private grievance, of grudges, angers, and disappointments. The proximity of those idioms raises questions about these ways of speaking divorce, and about the impact of the personal on Milton’s lofty summons to what he presents as the “general labor of reformation.” How do the inflections of the private life inform, perhaps deform, the articulation of the public good? And what does the history of one unhappy union have to do either with the nature of marriage or national struggle, that grand reform of church and state now under way?

Before proceeding with Milton’s program to bring revolution to the family, we might turn for a moment to his Areopagitica (1644), that great tract on behalf of freedom of the press. As in The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce, strands of private motives and public ideals are mixed together, and perhaps this mixing of registers is even more curious in Areopagitica than in the divorce tracts because of the surprise that Milton’s personal history—his sense of humiliation at the hands of the licensing censors, his resentment at being treated “like a punie with his guardian”—should be mingled with the inspiring, indeed heroic, rhetoric of Areopagitica. As in the divorce tracts, the trail of rhetorical evidence, the language of selfhood and self-regard, reveals how a personal history of resentments invades the realm of the public good proclaimed in the near-universal language of freedom, reform, and renovation. As before, we might ask about the impact of this mingling, about the balance of high against low, and of the rhetorical, even ethical, effect of these inflections and admixtures. Do petty complaints, private resentments, and personal vindication compromise Milton’s great vision of human freedom or of the victory of truth over falsehood in the never-ending struggle to repair the ruins of mankind? And if they do, at what cost to the purity of spirit in which revolution is proclaimed? Or are they simply extraneous rhetorical matter, leftovers from the prompts of composition? But as mere leftovers they draw our attention to the personal energy and drive, to the rhythm of injunction and argument, to that layering of grand principles over deep personal argument that marks so much of Milton’s polemical work.

Do petty complaints, private resentments, and personal vindication compromise Milton’s great vision of human freedom or of the victory of truth over falsehood in the never-ending struggle to repair the ruins of mankind?

At the end of this decade of revolutions, Milton was locked in hopeless combat with the ghost of a martyred king. His Eikonoklastes (1649) strenuously denied the personal within the public; indeed, Milton denounced his antagonist, and repeatedly, in those very terms, decrying the king’s interposition of “private reason” over the law, his elevation of “private conscience” over “public calling,” his thrusting of the “privat and overweening Reason of one obstinate man” against the whole kingdom. Indeed, the term ‘private’ runs like a bright thread of condemnation through Milton’s assault on Charles I. And yet, traces of Milton’s own private reasonings and personal ambitions as well as self-regard are written through the whole. First in Milton’s intricate maneuvers at the opening of Eikonoklastes to deny his agency in answering the king’s book: it was no “fond ambition” nor “the vanity to get a Name,” nor was he “so destitute of other hopes and means, better and more certain to attain it.” It was for the sake of others, for those who in simplicity or ignorance failed to penetrate the gaudy sham of Eikon Basilike, that Milton took on this thankless task. And yet Eikonoklastes is also marked by the insistent presence of the first person singular of its author: Milton’s “I” recurs 99 times through this image-breaking whole. By the end of his tract, Milton has reversed his opening claims of self-denial; now he celebrates his happiness in having “set free the minds of English men” from the captivity of kings, in having done a work “not much inferior to that of Zorobabel; who by well praising and extolling the force of Truth . . . conquered Darius and freed his Country and the people of God.” High ideals bound to strategies self-defense: the familiar dissonance of blame and opprobrium tied to lofty abstractions and to acts of grandiose self-imagining and self-mythologizing. John Milton in the 1640s was a revolutionary constituted of many motives, languages, and ideals.

“Home he returns a married man, that went out a bachelor”

Turning more closely to the matter at hand, the matter of revolution and divorce, requires a biographical note to help us navigate Milton’s presence in the world of the 1640s. He was born in 1608 and with the privileges of his social and economic status, what we would call his upper-middle-class origins, he attended the best schools—St Paul’s in London as a child; Christ’s College, Cambridge, as a young man. Returning home from college, he spent six years reading, studying, and beginning to write, this in his father’s house and on his father’s dime. Near the end of the 1630s, age 30, he took a grand tour, spending over a year on visits to France and Italy, not, by the way, nurseries of political revolution or civic renewal nor bastions of spiritual reform in the age of the Baroque; together with Spain, they were the home ground of ‘Popery and slavery’.

In the early 1640s, soon after returning to England, Milton put into print several tracts against clerical tyranny, blasting the Church of England and denouncing its fixed liturgy. Perhaps the denunciation of church tyranny was motivated by Milton’s travels in popish lands, but these themes he shared with other reformers, and the tracts hint at very little of the private life. However, in the longest of the tracts, The Reason of Church Government (1642) Milton makes a digression to proclaim openly, proudly, his learning, his literary merit and ambition—his bona fides for speaking on public matters, for meddling as it were in the high affairs of Parliament and the Westminster Assembly of Divines. But there is nothing in the least bit hidden or veiled in this personal digression; whatever we think of its efficacy, the story of Milton preparing to don his singing robes or to sit “in the cool element of prose” is, if not without ego, certainly without much guile or guilt or perhaps even self-deception.

What followed Milton’s entry into public debate over church governance, was a different matter altogether. We are now in the early months of 1642, a momentous year in Milton’s private, and the nation’s public, life: the civil wars would begin at the end of that summer; the spring was marked by the opening of a different struggle. In May of 1642, at the bidding of his father, Milton visited one Richard Powell to collect an interest payment that Powell owed on a loan from John Milton, Sr. We do not know if Milton obtained the payment, but he incurred his own, rather different debt: he came home “a married man that went out a Bachelor.” Within a month of this marriage, Mary Powell—Richard’s seventeen-year-old daughter—fled Milton’s household, leaving her new husband deserted and disgraced. We do not know the details of this story, but what seems to have been intended as the bride’s brief reunion with family stretched from a month into nearly three years. In the interlude Milton wrote his divorce tracts, hoping to be rid of Mary Powell and to find another bride. It does not take huge powers of deduction to think that marital grief led to the advocacy of reform, though some Milton scholars have tried to deny the significance of the private and the incidental in this matter of Church doctrine and civic reform. But it is in fact the full terms of Milton’s argument, the languages of his advocacy both high and low, the disembodied model of marriage and denunciation of that union as human bondage as well as his figures of self-imagining as “a blameless creature,” a “discreet man,” indeed one of the “soberest and best governed” of men, that together summon our attention and reveal to us the sources of energy and the angles of engagement in Milton’s labor. High rhetoric overlays but does not obscure the private disturbances that Milton brought to print.

In the most elevated terms, Milton urges an understanding of marriage altogether spiritual and intellectual, a union nearly without bodies, for in the divorce tracts he repeatedly figures marriage as the joining of rational souls, as the mind’s solace and satisfaction, its source of “comfort and peace,” an apt and cheerful conversation that hedges a man against the solitary life. The bond of wedlock, in this argument, is an altogether “intellectual and innocent desire”; God intended marriage as the highest form of social and intellectual companionship: “human society must proceed from the mind rather than the body, else it would be a kind of . . . brutish congress.” Of God’s donation of Eve to Adam, of God’s reaching into the very body of man to create woman—bone of his bone, flesh of his flesh—and of the earthly and material nature of all creatures, Milton says nothing at all. He presents the Scriptural verse at the center of his argument, Genesis 2:18, shorn of context, isolated from surrounding verses: “And the Lord God said, it is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him an help meet for him.” Note the slight shift in the language of Genesis 2:18 (KJV) when Milton quotes the verse; he generalizes and makes universal God’s command “that man” should not be alone—this from the more particular language of Scripture: “ . . . it is not good that the man should be alone.”

With lofty assurance and the supposed approval of learned interpreters, Milton declares God’s intentions and meanings:

And what his chiefe end was of creating woman to be joynd with man,

his own instituting words declare, and are infallible to informe us what

is marriage, and what is no marriage: unless we can think them set there

to no purpose: It is not good, saith he, that man should be alone; I will

make him a help meet for him. From which words so plain, less cannot

be concluded, nor is by any learned Interpreter, then that in Gods intention

a meet and happy conversation is the chiefest and the noblest end of marriage: for we find here no expression so necessarily implying carnall knowledge, as this prevention of loneliness to the mind and spirit of man.

Neither generation nor carnal desire, but companionship alone is the ground of marriage. Nor are Adam and his helpmeet the lone protagonists in this drama: others stalk the pages of Milton’s tract where we glimpse the hapless male as a “blameless” creature taken off guard when expected solace turns “to perpetual sorrow.” So it will often happen when those “who have spent their youth chastly,” almost by definition the least practiced in such affairs, venture into the dangerous waters of matrimony. How should such a man know “that the bashful muteness of a virgin may ofttimes hide all the unliveliness and natural sloth which is really unfit for conversation . . . a mute and spiritless mate.” And whose experience animates the figure of that chaste, that guileless man, perhaps “in some things not so quick-sighted while [he] hastes too eagerly to light the nuptial torch”? Libertines with “wild affections” have had many ‘divorces’, as it were, to instruct them in these treacherous matters, but “the sober man honoring the appearance of modesty, and hoping well of every social virtue under that veil, may often chance to meet, if not with a body impenetrable, yet often with a mind to all other due conversation inaccessible, and to all the more estimable and superior purposes of matrimony useless and almost lifeless.”

We are not dealing, here, with a rebel against the norms of patriarchy, an Adamite demanding the abolition of marriage, or a radical advocating utopian reform of relations between the sexes. No, divorce in Milton’s account may be polemically associated with grand reform, with completing the imperfect reformation of the Church of England, but its advocacy was driven by Milton’s “practical” notion that divorce from Mary Powell would enable him to be rid of an unsatisfactory mate and contemplate marriage with another, and by what must be read as deep personal hurt—the rejection and disregard of his lawfully wedded wife.

The drama could hardly be more transparent; the story of marital disaster is the story of John Milton’s union with Mary Powell: a mind inaccessible, unfit for conversation, a mate, in John Milton’s telling, useless and nearly lifeless. However else Milton’s learned searching of Scripture validates divorce, at least to his satisfaction, there is no question that his striking, his revolutionary call to reform divorce directed at Parliament and the Westminster Assembly of Divines began in the summer months of 1642 when its author was abandoned in his household on Aldersgate Street, and his wife, Mary Powell Milton, was some fifty miles away, at home with family in Foresthill near Oxford.

We are not dealing, here, with a rebel against the norms of patriarchy, an Adamite demanding the abolition of marriage, or a radical advocating utopian reform of relations between the sexes. No, divorce in Milton’s account may be polemically associated with grand reform, with completing the imperfect reformation of the Church of England, but its advocacy was driven by Milton’s “practical” notion that divorce from Mary Powell would enable him to be rid of an unsatisfactory mate and contemplate marriage with another, and by what must be read as deep personal hurt—the rejection and disregard of his lawfully wedded wife. Perhaps she had said to her husband ‘I will pay a brief visit to family and return in a fortnight’; home she came, but not in a fortnight. Nearly three years later, she returned to the house on Aldersgate Street, now with her royalist family in tow—mother, father, and five siblings under the age of sixteen. The royalist Powells would share hearth and home with this deeply committed Puritan and parliamentarian, a vociferous advocate of church reform and the author of four extraordinary tracts on divorce. It must have taken a good deal of forbearance on Milton’s part to be closeted with a desertrix, an “intolerable adversary,” and the large family that accompanied her back to London, the Powells having lost their home in Oxford on account of the father’s “debts and tangled finances.” That delinquent royalist had not only defaulted on his own properties, but as well on the interest that he owed Milton, and on the dowry promised at marriage.

Perhaps for us, these events on Aldersgate Street would have been a prompt for divorce, but for Milton it was the events of the past, it was Mary Powell’s denial of family and family life in 1642, her refusal to return to her husband, indeed to answer his letters, that turned this ‘family man’—guardian of his young nephews, succor to an ageing father—into a revolutionary in matters domestic. That he was aware of just how daring was such advocacy, his advocacy, Milton records in the address to Parliament that he wrote to preface of the second edition of the Doctrine published just months after the first. There, Milton urged—defensively, self-consciously—his own high authority and authorship: if a man “be gifted with abilities of mind that may raise him to so high an undertaking . . . if his resolutions be firmly seated in a square and constant mind, not conscious to it self of any deserved blame, and regardless of ungrounded suspicions . . . of idle descants and surmises” then Parliament will rejoice “that the truth be preacht.” Milton’s enunciation of high ideals and high motives ties together the protagonists of The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce, Areopagitica, and Eikonoklastes—three of his most important revolutionary tracts of the 1640s. What also binds the tracts together and of course binds them to their author, even when he published anonymously, is Milton’s self-imagining, his self-mythologizing, and, yes, the self-regard which compounded learning and valor with defensiveness and self-pity, a sense of self-importance but as well of vulnerability, of a certain susceptibility, to the accidents and materiality of this world.

I have alluded to a tradition of Milton scholarship that would deny—perhaps out of respect for Milton’s own insistence on high motives and high ideals—the tangle of personal experience with reforming argument, but to do so narrows the palette of Milton’s prose. Perhaps it protects Milton from a kind of modern suspicion or skepticism but it also protects his prose from its own complexity, from the harmonies, or indeed disharmony, of one kind of story overwriting another. To deny that high ideals can emerge from within the private life, indeed from within the body as from within angers and disappointments, from within the needs of vindication, ends up idealizing the author by narrowing the range of the sources, rhetorical and emotional, that drove him repeatedly to the lists. Of course we know Milton best as the sublime poet of Paradise Lost, but if we measure the energy and output of Milton as prose polemicist (14 of the 18 volumes of the Columbia Milton contain his prose writings) against that of the sublime poet we can gain a sense of the depth of Milton’s commitment to advocating on behalf of revolution in church and state. The divorce tracts also give us an understanding of the importance of the life that Milton lived in the body, within home and household, within his often difficult family relations, the importance of that life to the revolutionary work he performed in the 1640s within the newly energized medium of print polemics and, of course and in the end, to the poetry that he wrote after he had all but retired from the public fray.

Milton’s prose is quoted from, John Milton: A Critical Edition of the Major Works, ed. Stephen Orgel and Jonathan Goldberg (Oxford University Press, 1991).