John F. Kennedy, our 35th president, was assassinated in Dallas in 1963. He had won the presidency in 1960 in a very close election. His martyrdom created a Camelot image to his presidency and many were moved by the young family he left behind. Almost sixty years ago, and in the earlier part of the twentieth century, different mores determined appropriate press coverage and behavior generally. In more recent times, we have learned a great deal more about our political leaders, past and present. Knowledge and consequences changed. President Kennedy is the subject of many books and articles and is no longer viewed with rose-colored glasses.

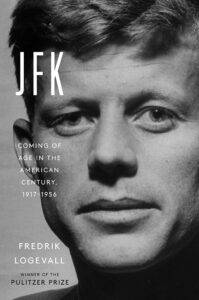

Fredrick Logevall, a historian at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, has published the first of a two-volume biography of Kennedy.

Entitled JFK, Coming of Age in the American Century, 1917-1956, the first volume is lengthy (650 pages of text) and not strictly a JFK biography. The first two-thirds deal as much with Kennedy’s father and his older brother as with the president, and the volume also offers selective background on events of the time. Logevall’s work presents various practices and personages with which his fellow historians would be aware. Students and laypeople will become more familiar with the Kennedys and their milieu with this book. Logevall seems to have liked his ostensible subject, although he does not gloss over failings. There are a number of themes implicit in his analysis that are worth pointing out, as they highlight both Kennedy’s life and career and the political and economic circumstances of his era. Because there is nothing new under the sun, some even echo today as we enter the third decade of the twenty-first century.

The rich are different than ordinary folk because their money buys access and influence. The Kennedy family patriarch was nouveau riche. Although we do not learn how he made his money nor how much he accumulated, we can safely assume the total was substantial. Although his eldest sons, Joe and Jack, had mediocre grades at best, they were admitted to Harvard and matriculated there with “gentleman’s Cs.” Jack had numerous lengthy hospitalizations beginning as a boy. Certainly, only the very well-off could afford the degree and length of care he received.

Students and laypeople will become more familiar with the Kennedys and their milieu with this book. Logevall seems to have liked his ostensible subject, although he does not gloss over failings.

Perceived wealth and power can also give you an in. With his rich father the ambassador to the Court of St. James, the future president had entree to many movers and shakers in Europe in the 1930s. That access inspired his senior thesis. Logevall notes his subject’s affability and attractiveness, but connections did not hurt.

The Kennedys were well aware of discrimination based on Irish Catholicism. Although Irish pols dominated elective office in the city of Boston, Protestant Brahmins dominated in other areas. Joe and Jack Kennedy were denied admission to the two most prestigious clubs at Harvard. Logevall finds it possible that a non-Irish third party was necessary to acquire what was to become the Kennedy compound at Hyannisport. However, the author does not address discrimination against other groups, particularly Blacks, to any discernible degree. He mentions the Black vote in terms of Jack Kennedy’s House and Senate campaigns in Massachusetts but does not mention that Boston had a very small Black population when compared with cities with a stronger industrial base. Nor does he detail the extent of de jure and de facto segregation that Blacks endured throughout the country. Apparently, Logevall feels, based on contemporary sources, that Kennedy treated everyone, including the non-wealthy and members of minority groups, with equanimity in personal interactions, including on the battlefield. However, his loyalty lay with his family and a small group of male friends.

A major focus of Logevall is whether President Kennedy echoed his father’s views. The elder Kennedy was an appeaser. He backed Chamberlain’s accession to Hitler’s demands at Munich and opposed the declaration of war by Britain and France when German troops moved into Poland. He was then the U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain and his various pronouncements did not sit well with President Roosevelt. A couple decades later he opposed the Cold War. From letters, diaries, and other sources, it seems clear that the future president did not echo his father’s strident views. His older brother, Joe Jr., did. John F. Kennedy was fiercely loyal to his family. He enjoyed the monies his father invested in his campaigns but kept him under wraps. He did take strategic campaign advice from him, though, and used his contacts when needed.

John Kennedy’s poor health and his womanizing were secrets to many voters. There was no social media then and press boundaries were narrower. Logevall deals with both issues at length. He feels the Kennedy men learned their infidelity from their father and that women were objects, not equals to them. In the 1950s, information about his very serious health condition or the women in his life would have been fatal to the election to office. The Kennedy people kept the secrets.

Logevall treats JFK’s role in the McCarthy period. However, he does not discuss the effects of that era in its totality. McCarthy became the symbol of a time of red-baiting which created havoc in politics, Hollywood, universities, in many other places. “Are you now or have you ever been?” Many lost their livelihood and some were imprisoned for refusing to name names. It was a witch-hunt. To this day, the sobriquet communist or socialist is used against political opponents in the negative campaigning that began in intensity in the 1980s.

JFK did not participate in the censure vote that the Senate took against McCarthy. Although he was not a fan of the Wisconsin senator, he apparently did not want to alienate Irish Catholic voters who were in his corner and Kennedy’s father was McCarthy’s friend.

JFK did not participate in the censure vote that the Senate took against McCarthy. Although he was not a fan of the Wisconsin senator, he apparently did not want to alienate Irish Catholic voters who were in his corner and Kennedy’s father was McCarthy’s friend. His younger brother Robert worked for McCarthy’s committee and entertained him at his Virginia home. Logevall notes that work for that committee only lasted 10 months. For liberals no doubt that was 10 months too long. For John Kennedy, this was not a courageous profile.

Kennedy was a general supporter of civil rights and also recognized the need of the United States to acknowledge the desires of people in colonial lands. Yet, though those ideas appeared in articles, they did not affect his behavior in Congress or the Senate. He had to work with the powerful Southern segregationists, all Democrats then, who chaired committees and could block legislation. And, to this author he is a cold warrior who subsumed his feelings about Asian and African peoples and the need to understand their yearnings in order to contain the Soviet Union.

Finally, Logevall raises the question of President Kennedy’s authorship of two books attributed to him. His senior thesis became Why England Slept (1940), a published work that sold well. Kennedy used his largess to hire researchers and editors for this project. It seems unusual to have paid help on a thesis but, as Logevall notes, his input is clear. His father did help to find a publisher for the thesis.

The second case is dicier. The question persisted for years as to who wrote Profiles in Courage (1955). Just before he died, Theodore Sorensen admitted he wrote it with considerable input from Kennedy. Many politicians use ghostwriters for books. Today dual authorship has become more common in memoirs. But John Kennedy received a Pulitzer Prize for this work as sole author. This biographer does not seem upset at this but many critics still abound.

Overall, this biography is lengthy and includes certain extraneous information. At other times, it could use a little more background. It also might have profited the author to clarify dates and which Kennedy is which. However, it does take one back in time and gives a greater understanding of a man whose impact belied his brevity in office.

Today dual authorship has become more common in memoirs. But John Kennedy received a Pulitzer Prize for this work as sole author. This biographer does not seem upset at this but many critics still abound.

Even so, questions will remain about his career and accomplishments and the debate will continue. Soon, few will be around who voted for him or observed him on television. And his mystique will fade more. He was a twentieth-century man and a twentieth-century politician but he seemed like fresh air and change because of his youth and verve. Logevall’s biography adds to the literature that students and history buffs can use to judge for themselves.