Imagine St. Louis, Missouri a century ago at the height of the Spanish influenza. World War I had finally ended on November 11, 1918. On Armistice Day, St. Louisans flooded the downtown intersection of Olive and 12th Street to celebrate, even though city health commissioner Dr. Max C. Starkloff’s quarantine was still in effect. Starkloff’s sanitary measures ensured St. Louis had the lowest death toll of any city its size in the United States.

Yet, not all St. Louisans went unscathed.

Twenty-eight-year-old Emilie M. Fisbeck Temper would have been about six months pregnant when her husband Hubert Marton Temper, age 36, died from the Spanish flu on November 30, 1918. Historians believe the 1918 flu infected 40 percent of the world’s population in a mere 18 months, including President Woodrow Wilson, who contracted the disease while negotiating the Treaty of Versailles in early 1919 (Wilson survived the flu and lived for five more years). No one was immune to the flu’s deep reach.

During the global pandemic, which killed an estimated 50 million people—more than all of World War I’s casualties combined—Emilie’s father and brother also died. When the English poet Wilfred Owen wrote of the Great War’s hell in his 1917 poem “Anthem for Doomed Youth”, he may as well have been writing about the sad state of the grieving Temper family and millions like them: “And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.”

During the Tempers’ time period, Cherokee Street, running east from the DeMenil home (1849) to west from the Lemp Brewery (1862), bisected a bustling neighborhood with grocery stores, a German bakery, a German butcher shop, and St. Louis’s first nickelodeon, which in 1918 showed silent films such as The Romance of Tarzan and Salomé.

Consider Emilie’s compounding losses: the numbing grief of losing her spouse, father, and brother, and then the challenge of acting as the sole breadwinner and parent of a soon-to-arrive baby, six-year-old daughter Myrtle, and nine-year-old son Milton. Emilie’s mother Amalia and sister Stella Fisbeck also lived with the Tempers in their rented home, and they provided solace as Emilie faced these crushing blows.

Consider this too: Every era tends to think theirs is the most difficult, amazing, or inexplicable time period, but historians would remind us that this assumption is the folly of myopic thinking. The same can be said for the past century on Cherokee Street, the working-class neighborhood and street where Emilie Temper and her matriarchal family lived, played, and worked on or near during the height of the Roaring Twenties, Prohibition (1920), the Great Depression (1929-1939), World War II (1939-1945), and more.

On February 24, 1919, Emilie gave birth to her final child, Wilbert John Temper, whom everyone called Bill, in the westernmost house of Bardenheier Row, located at 2211 Cherokee Street in St. Louis, Missouri. Wilbert was so named as a combination of his late grandfather and father’s names, William and Hubert, said Robert L. Temper, age 75, the late Bill’s son and Emilie’s grandson.

The social ecology of a neighborhood, like the businesses and homes surrounding Cherokee Street, is constantly shifting and evolving, according to Dr. Ness Sandoval, co-director of Saint Louis University’s Public and Social Policy Program. During the Tempers’ time period, Cherokee Street, running east from the DeMenil home (1849) to west from the Lemp Brewery (1862), bisected a bustling neighborhood with grocery stores, a German bakery, a German butcher shop, and St. Louis’s first nickelodeon, which in 1918 showed silent films such as The Romance of Tarzan and Salomé, starring Theda Bara, American cinema’s original “vamp” and one of the first celluloid sex symbols.

Around Temper’s time, immigrants from Hungary, Switzerland, Germany, Yugoslavia, Belgium, Croatia, Austria, Bohemia, Lithuania, Romania, and Turkey lived in and around Cherokee Street, according to St. Louis historian NiNi Harris. A hundred years later, Cherokee Street is still a global crossroads—Sandoval’s demographic data highlights immigrant residents from Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, Cuba, China, Korea, Vietnam, Somalia, Iraq, and beyond.

“Cities are living, breathing creatures,” art historian Chris Naffziger said when discussing what makes Cherokee Street one of the most historically intact streets in St. Louis today. “Let’s not make the mistake of arbitrarily romanticizing one period of history over another.”

• • •

Women of Cherokee Street: (from left) Emilie Temper, her sister Stella Fisbeck, and their mother Amalia Fisbeck.

(Courtesy Robert L. Temper)

Half a century after Emilie Temper’s harrowing winter of 1918, a cheerier remembrance of the historic Cherokee-Lemp District emerges. Pat Thomann’s Saturday mornings on Cherokee Street in the 1950s and 1960s left such a deep impression that Thomann, age 71, said, “I wish my daughter could have experienced that childhood.” After Thomann helped her grandmother scrub the steps of their family home, located on Magnolia and California, in the tradition of the “scrubby Dutch” (St. Louis’ Germans’ cleanliness-is-godliness mindset, a Midwestern mispronunciation of ‘Deutsche’) young Pat’s Hungarian family—grandmother, mother, and Pat’s two sisters—would walk to Cherokee Street for Saturday-morning kicks.

“It was the most wonderful neighborhood to grow up in,” Thomann recalled of Cherokee Street’s commerce and culture. As a child, Thomann loved exploring the street’s businesses—Woolworth’s, Morris Variety Store, a Globe Drugs (built in 1913, now Art Farm), and a Neisner’s “five cent to one dollar” store, among other old-school stores.

“You met everyone in the neighborhood on Saturday morning,” Thomann said of her jaunts.

Half a century after Emilie Temper’s harrowing winter of 1918, a cheerier remembrance of the historic Cherokee-Lemp District emerges. Pat Thomann’s Saturday mornings on Cherokee Street in the 1950s and 1960s left such a deep impression that Thomann, age 71, said, “I wish my daughter could have experienced that childhood.”

Her family would often venture into the double-story Morris Variety store, the one with the “rickety old steps.” Once inside the kitchenware section, her mother and grandmother would linger over milk glass dishes and vases while the children sprinted off to Walgreens soda fountain and bought 5-cent cherry phosphates or visited Favorite Bakery to purchase Thomann’s favorite, the cream horn, a nostalgic pastry whose North American origins trace back to the Mennonites of the Austrian-Hungarian empire.

“It was the most beautiful place,” Thomann said of Neisner’s (2700 Cherokee Street, now Angel Boutique Resale Shop). Passersby may still observe the wrap-around display windows, the diamond-patterned facade at the top of the two-story brick building, and the rising sun set above a middle window.

During Thomann’s childhood, she remembered Neisner’s “huge wooden staircase, handkerchiefs, and Evening in Paris perfume.” Most women in the neighborhood would put the indigo bottle, once empty, on the upper sash of the windows to filter in cool, blue light.

“People would line up around the block to dance there [Cherokee’s Casa Loma],” Thomann remembered. She is pleased to learn that people still do, 50 years later, though not always to jump, jive an’ wail. In 2018, the Casa Loma hosts “Midget Wrestling,” male strippers, and Mexican dance bands.

“Is the Casa Loma still open?” Thomann asked, eyes twinkling. Thomann was delighted to hear that the ballroom was still open and promised to return, if only to dance one more time on the “floating” tongue-in-groove maple floor, cushioned by one inch of rubber. Beginning in 1927, the Casa Loma was first known as the Cinderella Ballroom and then rechristened as the Casa Loma in 1935. Among those who have entertained at the Casa Loma were singer Frank Sinatra, jazz great Louis Armstrong, bandleaders Glenn Miller and Guy Lombardo, 1950s teen idol Pat Boone, and 1960s Tonight Show bandleader and trumpeter Doc Severinsen.

“People would line up around the block to dance there,” Thomann remembered. She is pleased to learn that people still do, 50 years later, though not always to jump, jive an’ wail. In 2018, the Casa Loma hosts “Midget Wrestling”, male strippers, Mexican dance bands, private parties for wedding receptions and quinceañeras, Big Gaye Soirée’s “A Night in Oz”-themed Pride Weekend festivities with a rainbow-colored Arch and the tagline of “a queernormous celebration of epic proportions,” among many other acts and events. It has come a long way since Pat Boone crooned there.

• • •

Well before Cherokee Street was even a rut in the mud, history tells us the Peoria tribe camped between modern-day Russell Boulevard and Arsenal Street. In the Carondelet neighborhood at 4420 Ohio Avenue, two miles from present-day Cherokee Street, sits St. Louis’s last prehistoric 40-foot mound associated with Woodland or Mississippian peoples (A.D. 400-1500). Sugarloaf Mound is the oldest man-made structure in the City. In 2009 the Osage Nation bought the riverfront property and in 2017 tore down the 1928 house which was built on top of the sacred mound. Eventually, the Osage Nation plans on building a interpretive center north of the mound.

“The mound survived the New Madrid earthquake, and bore witness when the river ran backwards,” wrote Andrew B. Weil, Executive Director of the Landmarks Association of St. Louis, Inc. “Ulysses Grant would have traveled past Sugarloaf while hauling firewood north on Broadway for sale in St. Louis. Sugarloaf stood when the riverfront burned, and cholera raged, when the railroad arrived, and when the Mississippi was finally spanned.”

Centuries after the creation of the Sugarloaf Mound, in the mid-1700s La Petite Prairie became one of the several common farming fields of the region. When Pierre Laclède developed St. Louis, he “insured that early villagers lived within sight and shouting distance of each other,” which meant villagers “walked to the fields beyond the tidy grid of planned streets,” wrote Dr. Patricia Cleary, a St. Louis native and professor of history at California State University-Long Beach.

If you wish to see a sliver of the Commons’ former majesty, what Cherokee Street was once upon a time when horses, cows, and hogs grazed and feasted upon wild strawberries, nuts, and roots, you can catch a glimpse at Lafayette Park, the last remaining piece of the St. Louis Commons and the oldest developed urban park within the Louisiana Purchase.

La Petite Prairie was but one tract of the vast and verdant open pasture of the St. Louis Commons. “Two thousand acres of communal land set aside when the village [of St. Louis] was mapped out,” wrote Cleary in The World, the Flesh, and the Devil: A History of Colonial St. Louis.

By the end of the 18th century, the St. Louis Commons fell into a sad state of disrepair (few were mending fences every spring before planting). The communal land quickly found its way into individual hands, and if you wish to see a sliver of the Commons’ former majesty, what Cherokee Street was once upon a time when horses, cows, and hogs grazed and feasted upon wild strawberries, nuts, and roots, you can catch a glimpse at Lafayette Park, the last remaining piece of the St. Louis Commons and the oldest developed urban park within the Louisiana Purchase.

Cameron Collins, of Distilled History blog fame and author of two books about St. Louis, wrote that not until the mid-1830s did city leaders move to sell parcels of the St. Louis Commons and actually turn the country into the city. The name Cherokee Street appears to be a random nod to the Native American tribe (as was Dakota, Osage, Winnebago, Chippewa, Utah for the Ute Indians) or leaders (Keokuk and Osceola). In fact, Cherokee Street was an exurb of sorts, according to St. Louis Patina blogger and art historian Naffziger, until residential and commercial buildings began construction in the 1800s and early 1900s.

These days Cherokee Street’s signature vibe is part Austin, Texas’s “keep it weird” aesthetic, Latinx mom-and-pop businesses, and local artists and galleries. “Everyone is a weirdo here,” admitted Kaylen Wissinger, owner of Whisk, a sustainable bakeshop east of Jefferson Avenue on the Antique Row section of Cherokee Street.

“I think that is really important and the neighborhood itself is a microcosm of different cultures and ethnicities,” Wissinger said. “Everyone who is down here is doing their thing for the love of it. There’s not an Old Navy or some other big-box store. We’re independent. Sure, it may be a bit stodgier on my side of the street, but there is a lot of soul in the diversity and grit of this place.”

Fostering locally-owned small businesses is fine by fellow Cherokee Street business owner, Rebecca Bolte, who owns ButtonMakers.net (2608 Cherokee Street, built in 1913 and originally home to a florist and tailor). Why favor big-box stores’ disposable building practices, Bolte asked during a meeting at Nebula, a co-working space founded in 2010 by one of Cherokee Street’s major developers, Jason Deem of South Side Spaces? “St. Louis is full of these walkable enclaves and these little stores and neighborhoods,” Bolte said. “I think it is really important to honor the history we have and keep the culture of small businesses and art alive.”

Beyond Cherokee Street’s liberated spirit, it is also very similar to Miami’s Calle Ocho, said Dr. Ness Sandoval, Saint Louis University sociologist and anthropologist. Calle Ocho represents Cuban businesses and economic activity more than where actual Cubans live, shop, and congregate in Miami.

Cherokee Street may not be the hub of a Latinx neighborhood per se, but as an economic enclave, Sandoval said, Cherokee Street is a powerful symbol of what Mexican and Latinx residents have contributed to the St. Louis region.

Sandoval and his Saint Louis University colleague Dr. Joel Jennings explained that one of the initial reasons Latinx residents in the 1980s chose to live and work in the Cherokee Street neighborhood and surrounding South City areas was the proximity of two Catholic churches, St. Francis de Sales Oratory (2653 Ohio Avenue, which was rebuilt in 1908 in a German Gothic Revival style, the only church of this style in the St. Louis area) and St. Cecilia (5418 Louisiana Avenue, built in 1906 in a Romanesque style). Both churches initially anchored the Latinx community to Cherokee Street, Sandoval and Jennings said.

While in the 1980s and 1990s Cherokee Street was a both a Latinx neighborhood and economic enclave, with greater economic mobility and affordable housing, more and more Latinx community members left to live closer to communities near the St. Louis Lambert International Airport. In 1980, the U.S. Census data indicated 24 percent of Latinx people lived in the City of St. Louis, Sandoval said; whereas, by 2016, only 15 percent of Latinxs lived in the City proper. Cherokee Street may not be the hub of a Latinx neighborhood per se, but as an economic enclave, Sandoval said, Cherokee Street is a powerful symbol of what Mexican and Latinx residents have contributed to the St. Louis region.

Not everyone agrees with Sandoval’s take, however. “It is important to reference a common misconception that people have been leaving this area,” said Carlos Restrepo, membership manager of the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce and a Cherokee Street resident. “Year after year more and more Latinos are living here; of course, there may be more hipsters living in the area, too, but at the core of this community, Hispanics have been living here since the 1980s.”

Restrepo said it was important to look at Cherokee Street’s surrounding neighborhoods, such as Benton Park West, Dutchtown, and Gravois Park, to get the full picture of where Latinxs live in the City of St. Louis and how the Latinx population is still thriving.

Sandoval shared a cautionary tale of over-reliance on the symbolic nature of Cherokee’s Latinx population. A couple years ago, Sandoval advised a Latinx youth outreach organization, which initially set up shop on Cherokee Street. The organization was shocked when the neighborhood did not provide the foot traffic it had hoped to serve. Other non-profits have used Sandoval’s data to provide outreach services in nearby Fairmont City, Illinois, where there are more Latinx youth. Ultimately, Sandoval said, knowing where Latinx culture resides versus where others go to consume Latinx culture is important.

While Cherokee Street may not have as many Latinxs living in the neighborhood as it once did, one thing is for certain: Cherokee Street benefits from the entrepreneurship of Latinx business owners, and we are still here, Restrepo said.

• • •

In the early 2000s, Black Bear Bakery, a worker-owned “anarchist collective,” moved their bakery from Jefferson Avenue and Pestalozzi Street to the 1907 Vandora Theatre (2639 Cherokee Street). The stately Vandora Theatre building has gone from being a site for the dawn of American cinema to providing a space for anarchist and philanthropic bakers. The Black Bear Bakery members rescued the Vandora Building from the Land Reutilization Authority of St. Louis in 2004, where tax-delinquent properties often go to the City to languish and die.

In addition to the 1948 Middleby Marshall oven Black Bear bakers baked in, the Collective also possessed a 1915 sourdough rye starter used for its award-winning bagels and breads. The starter was created by Samuel (Sam) Lickhalter, a Russian Jewish immigrant who owned and operated Lickhalter Bakery on Biddle Street, a mile from the City Museum, until the 1970s. The Post-Dispatch even reported on July 27, 1918 that Lickhalter was forbidden from baking for a week due to wartime rationing. The reason for the forced work stoppage? Lickhalter did not use enough substitutions in his baked goods nor did he make an accurate report to the government of how much flour he had on hand.

Meanwhile, almost a century after Lickhalter closed shop for a week, Black Bear closed its doors in 2016. At the end of 2017, Bridge Bread Bakery picked up where Black Bear Bakery left off. Fred Domke, founder and president of Bridge Bread, said he and his bakers are still using the 1948 oven Black Bear left behind. Bridge Bread is also noteworthy beyond inhabiting the old Black Bear Bakery—the organization supports and helps people experiencing homelessness by teaching marketable skills in a commercial bakery. According to the Bridge Bread website, “three-quarters of the income of sales goes to the Bakers in wages, taxes, and benefits.”

Like the Vandora Theatre, Lickhalter’s sourdough rye contains a tangible connection to the past, only this time you can taste it.

However, Domke does not have Sam Lickhalter’s 1915 sourdough rye starter. Robert Sweet, formerly of Black Bear, does have some of the century-old starter, which he confirmed by email. There is something mythical, even magical, about imagining the bakers who passed on this bubbling, yeasty goodness—of considering how the last 100 years of bacteria flavored the bread and gave it its signature tang. Like the Vandora Theatre, Lickhalter’s sourdough rye contains a tangible connection to the past, only this time you can taste it.

The evolution of the Vandora Theatre from an anarchist collective of bakers to bakers who are working to find jobs and homes is representative of what Cherokee Street offers visitors, local residents, and neighborhood businesses–a chance to redefine historic buildings for both profit and cause.

• • •

In the 1920s, to make a living after her husband’s death and Bill’s birth, Emilie Temper not only took in the laundry of neighboring residents but also worked as a pressfeeder for a printing press, according to NiNi Harris, who researched and wrote the historical marker outside of the five skinny red-brick row homes built by investor and German liquor-store magnate Philip Bardenheier in 1884.

In mid-September 1921, when Bill was two and-a-half years old, Emilie Temper would be arrested. Her crime? Sharing streetcar transfer tickets with Louis Zebrack, a shoe repairman who worked in the same building as Temper’s apartment. One wonders if the judge realized the widow he fined $24, equivalent to $313 today, had three children 12 and under at home? Or that Assistant City Counselor Paul Gayer said he thought the ordinance Zebrack and Temper were fined under was “the most unfair on the city’s books”? There is only so much one can surmise from reading old newspapers, but one can certainly imagine how desperate Emilie would have been to pinch every penny for her family.

In 1924, Emilie moved the Tempers to nearby Wisconsin Avenue, a block from Cherokee Street. This is the house Robert Temper, Emilie’s grandson, would remember. In fact, Robert had no idea his father Bill was born on Bardenheier Row until he was interviewed for this story.

“I often wondered how grandma raised a family on her own,” Robert said. “She was always a glass-half-full kind of person.”

As for Emilie’s job as a press feeder, Robert said at some point she went into business on her own. “I know she bought a printing press manual feed she installed in her basement on Wisconsin,” Robert said. “They had to rebuild the basement steps after that.”

Emilie’s work focused primarily on printing items for various businesses, her grandson Robert said. “She would print inserts and branded pencils the kids would get when their parents bought a pair of Poll Parrot Shoes,” Robert said. “She also printed labels for Red Goose [Shoes], too.”

Robert remembers the joy of playing in his grandmother’s basement, exploring rulers, pens, pencils, moveable type, and paper stock—a veritable wonderland for a small child. As an adult, one of Robert’s regrets when his grandmother passed on September 11, 1960 is, “I was too young to even think about keeping one of her printer’s drawers.”

In mid-September 1921, when Bill was two and-a-half years old, Emilie Temper would be arrested. Her crime? Sharing streetcar transfer tickets with Louis Zebrack, a shoe repairman who worked in the same building as Temper’s apartment. One wonders if the judge realized the widow he fined $24, equivalent to $313 today, had three children 12 and under at home?

Despite the lingering sadness of losing a father so young, Emilie’s three children had happy childhoods playing on and around Cherokee Street. The three children may have enjoyed a nickel show at Fred and Gertrude Wehrenberg’s first movie theater (of what would become the national chain) and definitely attended Shepard School, a half block from Cherokee Street and built upon Deutsche Evangelische Gottesacker, the German Evangelical Cemetery. By 1856, every inch of the old nine-acre cemetery was filled by the cholera epidemic of 1849. The Shepard School (3450 Wisconsin), named after the founder of the Missouri Historical Society Captain Elihu Hotchkiss Shepard, was built on top of the cemetery and opened in 1906 and closed more than a century later in 2009. Perhaps what Harris, the local historian, said of relocations and renovations is true: “They never get all the bodies out.”

Bill Temper attended the Shepard School, and his son Robert remembers for Bill’s tenth birthday his mother Emilie told him he

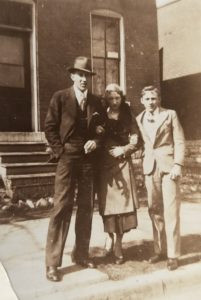

A dapper trio: Emilie Temper’s three children, from left, Milton, Myrtle, and Wilbert “Bill” Temper.

(Courtesy Robert L. Temper)

could have one of two gifts: a BB gun or to attend the Shepard School picnic. Bill chose the BB gun, but there are purportedly photos of the young boy “looking at a picnic he couldn’t go to,” Robert said. Like many children of the Great Depression, Robert said his father would often only get an orange for Christmas. When Robert and his sister Betty Jean were little, Bill would make “Christmas the event of the year.”

“We lived in a four-family flat on Oregon, a half block north of Cherokee,” Robert said of his family growing up. “Every December my dad would seal off the living room and decorate a gorgeous tree with lights. Later on, when we moved to Pennsylvania to a single-family bungalow, we’d festoon the tree with lead-based tinsel and when the Christmas Eve dishes were done, Dad would hit the lights and a toy train with a whistle would circle the base of the tree. Even now, Christmas is still a big deal.”

Before Bill created Christmas memories for his own family, Bill graduated from elementary school, and he worked as an errand boy, earning $7 a week, per Harris. When Bill died on August 23, 2003, his obituary extolled a lifelong membership at Saint Matthew’s United Church of Christ, the Mr. and Mrs. Club, Craftsman Masonic Lodge #717 AF & AM and the Anheuser-Busch Senior Club, Crestwood Senior Dance Club, and Retired Local Bottlers #1187. By all accounts, despite the rocky start, Bill Temper had a wonderful life.

Today the cemetery-turned-elementary-school designed by renowned school designer William B. Ittner will undergo yet another metamorphosis as 47 new apartments for the hipster and young professional set.

• • •

The inherent danger of nostalgia is all too often we dismiss the parts of history that seem, at first glance, alien and boring, vague and unclear, painful and unpleasant, and we remove the historical marker, or, even worse, walk right past it.

What is curious, but not unexpected, is nowhere on the Bardenheier Row marker is Emilie’s name mentioned. “For most of history,” Virginia Woolf wrote in 1929 in A Room of One’s Own, “anonymous was a woman.” The memories preserved and recorded on Harris’s marker are those of Emilie’s youngest son Bill, who simply remembered Emilie M. Fisbeck Temper as “mother.”

Today the cemetery-turned-elementary-school designed by renowned school designer William B. Ittner will undergo yet another metamorphosis as 47 new apartments for the hipster and young professional set.

Of course, there had to be more to the anonymous mother, the one who survived the Spanish flu and buried her husband, father, and brother. The woman who grew up on a farm in Hermann, Missouri, moved to the hustle and bustle of St. Louis’s Cherokee Street, and worked outside the home when many women did not because she had to. Emilie supported three children, her mother, and her sister, and she established a business of her own in the basement of her house on Wisconsin Avenue. She received the right to vote on August 18, 1920 at age 30, and Emilie’s name will finally be known by those who walk past the two-story brick building and the neighborhood, which contain some of her finest and darkest moments.

In the 21st century, Emilie M. Fisbeck Temper’s story began with one intriguing sentence, studied carefully while reading and re-reading NiNi Harris’s marker: “As a result, Bill was ‘raised by women.’” There had to be a story behind the nameless women who did the child-rearing, who persevered through the Spanish influenza and two world wars, who put one foot in front of the other, and just kept moving to build anew, to live again, to show their children another way.