In 2013, Luke Epplin, a freelance writer whose credits include The Atlantic, The New Yorker, Slate, and The Paris Daily Review, published an essay called “The Idiot’s Guide to Writing a Baseball Book.” In it, Epplin addressed the “young baseball beat writer itching to land a book contract,” and he offered “a surefire path for securing a book deal.”

Epplin urged the aspiring author to “simply pick a year—any year, really—and make a case for why that baseball season stands out from all the others. Follow one of these templates below and you’ll ink a deal in no time.” He then suggested four alternative paths: either “declare your chosen year the best in baseball history” or “group together a bunch of years, dub them a golden era,” or “connect the chosen year to your childhood, layer thickly with nostalgia” or “link your chosen season with larger social changes.”

Epplin may have tried to plant his tongue smartly in his cheek when he wrote this piece, but his essay disparaged or even dismissed a number of books highly regarded in the genre we might call popular baseball history, books by authors he did not shy away from calling out by name. Among those whose work he mocked were Cait Murphy (Crazy ’08: How a Cast of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads, and Magnates Created the Greatest Year in Baseball History), Robert W. Creamer (Baseball in ’41: A Celebration of The Best Baseball Season Ever—in the Year America Went to War), Roger Kahn (The Era 1947-1957: When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World), David Halberstam (Summer of ’49), author of “a book so sure of itself that it doesn’t even need a subtitle,” and Robert Weintraub (The Victory Season: The End of World War II and the Birth of Baseball’s Golden Age).

The title of this book, a work of popular sports history, comes from a story published in the Call & Post, Cleveland’s largest Black newspaper, after the city’s major league baseball club, the Indians, won the World Series for the first time since 1920.

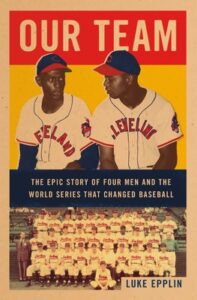

It is hard to read Epplin’s essay without envisioning a smirk on its author’s face as he pressed fingers to keyboard. And yet, in considering his own book, Our Team: The Epic Story of Four Men and the World Series That Changed Baseball, it is equally hard not to notice its author following his own, cynical counsel as he focused on one season, 1948, and asserted that the World Series in that year “changed baseball.”

The title of this book, a work of popular sports history, comes from a story published in the Call & Post, Cleveland’s largest Black newspaper, after the city’s major league baseball club, the Indians, won the World Series for the first time since 1920. Exulting that the team’s success had been bolstered by the substantial contributions of two African-American players, Larry Doby and Satchel Paige, the newspaper declared that “for the first time in American League history the Indians are OUR Team, without quiggle [sic] or qualification.” (285)

The integration of the Indians is a story that stands side-by-side, or perhaps as a sequel, to the more famous story of the integration of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Brooklyn executive Branch Rickey signed African-American Jackie Robinson to a contract in the fall of 1945. Robinson played minor league baseball in 1946 and joined the Dodgers in 1947, enduring all sorts of abuse. Yet, he won the National League’s Rookie of the Year award, and the Dodgers won the National League pennant, losing a memorable seven-game World Series to the New York Yankees.

Cleveland owner Bill Veeck was just one small step behind Rickey. He signed Doby to a contract in July 1947 and urged manager Lou Boudreau to insert him into the lineup right away. Yet, even though Doby had been an accomplished player with the Newark Eagles in the Negro National League, he came to bat only thirty-three times that season and got only five hits. Nineteen forty-eight proved to be Doby’s year to shine. Converted to an outfielder, he honed a renewed sense of plate discipline during spring training and earned a spot in the starting lineup. Moreover, he was joined on the Cleveland roster in July by Satchel Paige, without doubt the most celebrated pitcher in Black baseball history. Together, they propelled the Indians to a tie for first place in the American League, a victory over the Boston Red Sox in a one-game playoff to determine the pennant winner, and a four-games-to-two triumph over the Boston Braves in the World Series.

Epplin admits that “it is perhaps inevitable that the second team in Major League Baseball to integrate in the twentieth century would be overshadowed by the first.” (7) He insists, though, that, beyond Brooklyn, “there was another meaningful and dramatic narrative unfolding at the same time in Cleveland,” (7) and he presents the thesis that the “unlikely union” (7) of the four key participants in his story “would elevate new athletic idols and lead to the reevaluation of old ones, would remake sports as a business and the individual athlete as a brand, and would help puncture long-standing stereotypes that so much of White America harbored toward Black ballplayers.” (7) A tall order, that.

Veeck’s life and career would have been interesting even if he had not chosen to pursue integration. The son of a sportswriter-turned-Chicago Cubs president, he was a baseball lifer. As a young man, he worked for the Cubs and helped to plant the ivy that adorns the outfield wall at Wrigley Field to this day. He left Chicago and bought the minor-league Milwaukee Brewers before enlisting in the Marines during World War II. On Bougainville Island, an artillery piece misfired and sliced into his lower right leg, causing an injury so severe that it refused to heal. Partial amputations and multiple surgeries dogged Veeck for the rest of his life.

Veeck sold the Brewers in late 1945 and bought a ranch in Arizona, but his heart still pined for baseball. A few months later, he learned that the Indians might be for sale, and he put together a syndicate to purchase the club. Operating on a shoestring budget, Veeck got right to work, setting out to refashion the Cleveland club into a contender. More famously, he went to happy extremes to market his team, employing all manner of promotional gimmicks to bring fans to the ballpark, win or lose. Integration was only part of his plan, albeit an important part.

Doby was a native of Camden, South Carolina. Raised by his grandmother, he moved north to join his mother in Paterson, New Jersey, so he could attend that city’s integrated high school system. An outstanding multisport athlete, he began playing for the Eagles, using an alias to safeguard his eligibility for intercollegiate sports because he planned to attend Long Island University on a basketball scholarship. Faced with being drafted during the war, Doby enlisted in the navy, but the athletic ability he demonstrated at the Great Lake Naval Training Station got him a coveted job as a physical education specialist, kept him away from combat, and secured for him places on several naval basketball and baseball teams, some of them integrated. After the war, he rejoined the Eagles and excelled.

Had Paige not been a Black American, he certainly would have been a star in the major leagues. His prodigious talent as a pitcher was inimitable, and his innate sense of showmanship helped him create an attractive persona that made him rich. When he felt like it, Paige deigned to play for one or another team in the organized Negro Leagues, but more often than not, he capitalized on his own celebrity, showcasing his ability by traveling across the country, playing wherever the money was good enough. Defying the restrictions inherent in Jim Crow, he was his own man, “a representation,” Epplin writes, “of mobility, self-determination, and defiance.” (43)

Feller was baseball’s version of a child prodigy. He made his major league debut with the Indians in 1936 when he was only seventeen, and he was a twenty-game winner three times before enlisting in the navy just after Pearl Harbor. Just as important, he recognized early that since baseball was a business, he needed to become a businessman. He negotiated an attendance clause in his contract and, each off-season, organized barnstorming tours, featuring both Black and White players, that put substantial dollars in each participant’s bank account. Yet, after the war, it seemed as though his best years as a pitcher were behind him, and his contributions to the Indians’ success in 1948 were less than optimal.

Those familiar with the existing literature may be less enchanted with Epplin’s goal than those for whom his engaging story is new. None of Epplin’s four main characters has been forgotten.

Epplin told The New York Times that he intended to write a book about Veeck, but “reading through the archives of The Sporting News,” he said, “I kept seeing these four names coming up: Bill Veeck, Larry Doby, Satchel Paige, and Bob Feller. … I thought, the larger story is to be told here, through these four men.”

Those familiar with the existing literature may be less enchanted with Epplin’s goal than those for whom his engaging story is new. None of Epplin’s four main characters has been forgotten. All except Doby put his name on one or more memoirs, and each—Veeck especially—has been treated in biographies and other studies of the game, including Timothy M. Gay’s Satch, Dizzy & Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball Before Jackie Robinson (2010), a book that explores Epplin’s idea of the individual athlete as entrepreneur or brand. Factually, Our Team breaks no new ground, so its success depends on whether Epplin’s narrative can hold readers’ attention.

Make no mistake. Our Team is a wonderful book in this sense. It is easy to read. It tells an interesting story built on thorough research in newspapers and secondary sources, skillful organization, pleasant writing, and narrative drive. Epplin gives each of his four main characters equal attention in an account carefully woven out of the cloth of several seasons. For the baseball fan, either serious or casual, even if one’s favorite team is not the Indians, this book can provide several hours of pleasure.

Telling a good story and telling it well may be good enough, but Epplin’s book raises larger questions: what qualifies as good popular history? Academics have their own standards for academic history, but what should we expect from a book written by someone without academic credentials? Short of breaking new ground in the academic sense, what else should readers expect?

At a minimum, popular history should feature well-written, attractive prose. The narrative should be accessible. It should have pace. It should grip the reader. It should take note of previous work on the same subject, including scholarship. It should be accurate and avoid stumbling over previous errors or myths. Perhaps more important, it should tell us something that we do not already know.

Epplin’s book checks most of these boxes. His prose is pleasant enough, and the way he organized his story is ingenious. His research, amply displayed in endnotes and bibliography, allows him to include telling details and anecdotes throughout. Whether he holds the reader’s attention by telling us something new will vary, of course, from reader to reader. Most, I suspect, will be charmed throughout, but those who come to this book having already read about its main characters may depart disappointed.

Of more concern to some readers is that Epplin never proves his thesis. Did the “unlikely union” of his four protagonists “elevate new athletic idols and lead to the reevaluation of old ones”? Did they “remake sports as a business and the individual athlete as a brand”?

Authors of popular history—or their editors—sometimes shy away from subtlety, mystery, the unknown. Confronting the story, first told by Veeck himself in Veeck—As in Wreck (1962) that he wanted to buy the Philadelphia Phillies in 1943 and restock the roster with players from the Negro Leagues, Epplin accepts it without question. “Decades later,” he writes, “some historians would cast doubt on Veeck’s intention of purchasing and integrating the Phillies, pointing to a lack of contemporaneous evidence and Veeck’s habit of embellishing and revising his memories in service of more entertaining stories.” Indeed, the argument over the veracity of Veeck’s assertion has a fascinating life of its own and has made for interesting history. It is a pity that Epplin tosses it aside, writing that “Veeck, however, stuck to his account,” as if the late iconoclast had spoken to his critics directly. Fictional newspaper editor Carleton Young told us to “print the legend,” but sometimes exploring it is worth the effort.

A few minor errors blemish Our Team here and there, but they are insignificant. Kenesaw Landis did not enjoy a lifetime appointment as commissioner. The St. Louis Cardinals were not yet known as the Gashouse Gang in 1934. The sport called major league baseball was not the business called Major League Baseball until decades later. But no matter. Of more concern to some readers is that Epplin never proves his thesis. Did the “unlikely union” of his four protagonists “elevate new athletic idols and lead to the reevaluation of old ones”? Did they “remake sports as a business and the individual athlete as a brand”? Did they “help puncture long-standing stereotypes that so much of white America harbored toward Black ballplayers”? Did the Indians’ run to the World Series championship in 1948 shine “a light forward for a country on the verge of a civil rights revolution”? Epplin’s narrative, as well-wrought as it is, does not directly answer these questions.

Perhaps the author should get the last word. The conclusion of his essay for The Daily Beast deserves to be quoted in full, so applicable is it to his own book: “So that’s all you need, more or less, to compose a winning book proposal: decide on a year, make a couple of lofty assertions, string together a handful of anecdotes about the era’s star players, tie in a few historical figures and events, and then coast through to the World Series. Oh, and if it weren’t abundantly clear, don’t skimp on the subtitle—if yours doesn’t include some combination of the words ‘best,’ ‘golden,’ ‘forever,’ ‘greatest,’ ‘last,’ ‘incredible,’ or ‘America,’ then you’re not quite ready for the big leagues.” Indeed.