In the history of baseball, there are plenty of players with style. Consider the cheery swagger of Babe Ruth, the cool grace of Joe DiMaggio, or the backwards-hat exuberance of Ken Griffey Jr.

But Rickey Henderson? Rickey dripped with style.

When Rickey strolled from the dugout to the batter’s box, he did it on his own time, putting the pitcher and catcher on notice: Rickey was the show. He settled into that deep crouch, shrinking his strike zone. He worked the umpires (he universally called them “Blue”) and muttered to himself (“C’mon Rickey. He can’t beat you with that.”) And if he smashed a laser-sharp single or earned a walk? The lead off the base. The waggling fingers. The air of defiance. Then, WHOOSH! He took off for a steal, powered by the tree-trunk-thighs of an NFL running back, culminating in a late, straight-on, nose-first slide that he likened to an airplane coming in for a landing.

There was more. In the outfield, Rickey had the trademark “snatch-catch,” when in one looping motion he caught a fly ball and slapped the glove off his hip. When he hit a big home run, he took a wiiiiiddddde turn around first base, and as he trotted around the bases, he picked at his uniform, as if disposing of tiny dead bugs. Rickey turned a baseball game into a series of personal confrontations, playing both the hero and the villain. “It’s Rickey time!” he sometimes announced upon walking into the clubhouse.

When Rickey strolled from the dugout to the batter’s box, he did it on his own time, putting the pitcher and catcher on notice: Rickey was the show.

The 1980s delivered new icons of American culture, some of whom needed just one name: Madonna, Bono, Prince. In baseball, it was Rickey time.

• • •

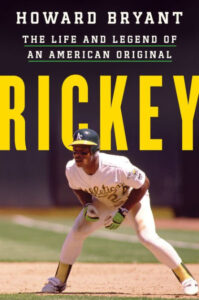

Howard Bryant’s Rickey: The Life and Legend of an American Original approaches Henderson as both a complex human being and a Black culture hero with multiple meanings. A senior writer at ESPN, Bryant has examined baseball’s tangled racial history in books such as Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston and The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron. Like these books, Rickey combines impressive journalistic legwork, clear narrative writing, and sensitive analysis of the unique burdens endured by Black athletes.

The heart of Bryant’s story resides in Oakland, California, where Henderson’s mother moved from Chicago when Rickey was a young child. Thanks to the second wave of the Great Migration that began during World War II—along with persistent patterns of racial segregation—Oakland’s schools and youth programs were a fount of Black athletic talent. Baseball stars Frank Robinson, Vada Pinson, and Curt Flood all played outfield for McClymonds High School, while NBA legend Bill Russell cut his teeth on the hardwood. Oakland’s next athletic generation included a number of major leaguers, including Henderson and All-Star pitcher Dave Stewart.

Even as a teenager, Henderson had a presence, a charisma, an “It Factor.” From his early teen years, he envisioned himself as a pro athlete. Though his true love was football, he lacked the grades to play in college, so he signed an offer with the Oakland A’s. Bryant vividly chronicles Henderson’s ascent through the minor leagues. From the beginning, he believed that he could be the greatest base-stealer of all time. He was not yet a star, but he acted like one. When John Kennedy, his “redneck” manager in Double-A Jersey City, was riding him, the teenage prospect called franchise owner Charlie Finley, who told Kennedy to leave Henderson alone.

He was not just fast and powerful—he was audacious, mesmerizing, with a touch of the ridiculous. In 1983 he first unveiled his “snatch-catch.” He did it, for the first time ever, on the final out of a no-hitter.

In 1980, Henderson’s first full season in the majors, Billy Martin joined the A’s. Over the next three years, the brilliant, volatile manager transformed a losing squad into championship contenders, and he elevated Henderson’s profile. Martin played favorites with superstars, and Henderson craved that kind of absolute support. In 1982, with Martin’s encouragement, Henderson broke Lou Brock’s single-season stolen-base record.

Yet Henderson did not need any particular manager to showcase his electric talent. In the eleven seasons from 1980 until 1991, he led the American League in steals ten times. He was worth the price of the ticket. He was not just fast and powerful—he was audacious, mesmerizing, with a touch of the ridiculous. In 1983 he first unveiled his “snatch-catch.” He did it, for the first time ever, on the final out of a no-hitter.

• • •

Rickey illustrates the new opportunities and pitfalls for pro baseball players in an era of national television and multi-million-dollar contracts. Henderson was “relentlessly capitalist,” (239) keeping an eye on every dollar earned and spent. He had a strong sense of his own economic value. Since his first minor league contract, he had burned that he was underpaid and exploited. In 1984, grumpy with his agent and contract, he forced a trade out of Oakland by withholding his best effort.

Arriving in pro sports in the wake of the civil rights and Black Power movements, Henderson expected equal regard, regardless of race. If he espoused any personal philosophy, it was almost classically conservative. As Bryant writes, “he believed that he was free—free to talk back to the fans or the newspapers, free not to sign autographs if he wasn’t in the mood or if some snotty fan acted like a little shit to him, free to yell at umpires, free to be polite or rude, and free to publicly demand to be compensated what he believed he was worth.” (196)

His sense of entitlement ruffled the old-school sensibilities of the White baseball establishment. “More than any other sport,” writes Bryant, “baseball demanded that Black and brown players adapt to the old ways of playing the game, which was to say, the white ways.” (121) Some managers and front-office executives resented Henderson’s individualism, confidence, and flair. Reporters called him a “hot dog” and portrayed him as a rube, a money-grubber, a man out for himself.

Arriving in pro sports in the wake of the civil rights and Black Power movements, Henderson expected equal regard, regardless of race. If he espoused any personal philosophy, it was almost classically conservative.

When Henderson joined the New York Yankees in 1985, team owner George Steinbrenner was fostering a dysfunctional culture, which included the return of his combative, alcoholic manager, Billy Martin. Meanwhile, ego-drenched columnists such as Dick Young and Mike Lupica expected athletes to express reverence for the privilege of playing in the nation’s cultural capital. But Henderson was wary of the press, and he refused to ham it up like Mets catcher Gary Carter, who was a media darling. In his first appearance in New York, Henderson blew past the assembled reporters, saying, “I don’t need no press now, man.”

So the Rickey stories always included a but. He became the Yankees’ career stolen-base record holder in just four seasons, but he operated by his own rules. He scored over 1,000 runs in the 1980s, but he took his time when recovering from injuries. He revolutionized the leadoff position by developing into a home-run threat, but he was either a comical or a sullen character. He was a perennial All-Star, but he never led the Yankees to the World Series. Was Rickey a loser?

Henderson’s return to Oakland answered that question. Upon a midseason trade in 1989, he joined a talent-rich A’s squad that featured power hitters Jose Canseco and Mark McGwire but had flamed out in the previous year’s World Series. Henderson transformed the A’s into a juggernaut. Oakland won the World Series in 1989.

The next year, Henderson won the MVP award, a sign that his complete game of speed, power, and batting discipline was finally earning the recognition it deserved. The year after that, he set the all-time stolen base record—when he was just thirty-two years old. And two years after that, Henderson served as a short-term sparkplug for the Toronto Blue Jays, helping them repeat as World Series champions. If Rickey Henderson never played another game after 1993, he would still have been a surefire Hall of Famer, a baseball legend.

• • •

Henderson kept playing. He signed for a third time with Oakland. Then San Diego and Anaheim. Back to Oakland for a fourth stint. Back to New York, this time with the Mets. Then Seattle, San Diego, and Boston. He played his final major league season in 2003, at age forty-four, for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

This final, extended, itinerant phase of Henderson’s career had two effects. First, he left an incredible legacy of numbers. Bill James, whose ideas on statistical analysis now shape the approach of every front office, once said that “if you split Rickey Henderson in half, you’d have two Hall of Famers.” (291) Henderson retired with over 3000 hits and almost 300 home runs. He stole 1,406 bases, 468 more than the next person on the list. He drew 2190 walks, breaking the career record set by Babe Ruth, and scored 2295 runs, surpassing the all-time record set by Ty Cobb. He broke that run record by hitting a home run—and sliding into home plate. To the end, Rickey had style.

The Rickey stories always included a but. He became the Yankees’ career stolen-base record holder in just four seasons, but he operated by his own rules. He scored over 1,000 runs in the 1980s, but he took his time when recovering from injuries. He revolutionized the leadoff position by developing into a home-run threat, but he was either a comical or a sullen character.

Second, Henderson developed into an endearing figure. After the 1994 labor strike and cancellation of the World Series, some of the tired old-school codes were eroding. Baseball could be a little more fun, a little more accepting of its characters. “The new generation no longer watched Rickey for what he wasn’t, but saw him specifically for what he was—and that was Rickey,” writes Bryant. “Far from being offended by Rickey Style, it was why they bought the tickets.” (301)

Yet Bryant carefully separates the man from the myth. He offers glimpses into Henderson’s long and complicated relationship with his wife Pamela, and he factually narrates how Rickey’s sister Paula accused him raping of her when she was twelve years old, as well as the subsequent legal ruling that exonerated Rickey. He does not excuse Henderson’s instances of unprofessional conduct, such as periodic sulks over his contract status, or his playing cards in the clubhouse with Bobby Bonilla while his teammates on the Mets lost an excruciating extra-inning playoff elimination game.

Bryant further relates the many stories of Henderson’s malapropisms and wince-inducing pronouncements. In 1991, when he broke the all-time steals record, Henderson proclaimed, “Lou Brock was the symbol of great base stealing, but today, I am the greatest of all time.” It was a tone-deaf declaration, since the genial, beloved Brock was on the field to help honor him.

Throughout the book, however, Bryant reframes Henderson through a Black perspective—an option rarely available during his playing career. Where many White reporters belittled Rickey’s intelligence and exaggerated his third-person references, Bryant sees a savvy figure who navigated the disadvantages of race, a proud man who demanded to be paid his worth, an exceptional athlete who knew and preserved his body, and a genuine person who was kind and cruel, generous and cheap, sweet and bitter, a champion and an also-ran, a hero and a fool. Rickey is a fully fleshed portrait, resistant to stereotype, the type of rendering that any biographical subject deserves.