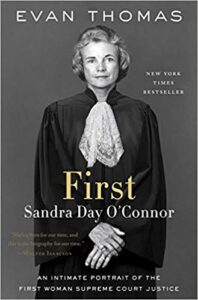

Two of the most noteworthy disclosures in Evan Thomas’s biography First: Sandra Day O’Connor came to light shortly before the book’s publication in March 2019[1]: The previous October, a National Public Radio broadcast recounted how, as a law student at Stanford in the early 1950s, O’Connor received a marriage proposal from her classmate—and future Supreme Court colleague and Chief Justice—William Rehnquist.[2] Also in October, O’Connor announced that she was stepping out of public life because of dementia, likely Alzheimer’s disease, the same mind-ravaging curse that afflicted her husband and prompted her to give up her seat on the Court prematurely so that she could care for him.[3] One could easily regard the early release of such information as previews of the very personal study of O’Connor that the book aims to achieve, as conveyed by the inviting language on the book’s jacket: An Intimate Portrait of the First Woman Supreme Court Justice.

The promise of intimacy offers one path to follow through Thomas’s book. An additional path rests on O’Connor’s gender—which made her “first.” In this review I travel both paths, ultimately showing how intimacy and gender in Thomas’s hands converge to raise disconcerting questions about the entire project.

A. Intimacy

To develop the promised intimacy, Thomas, like any good biographer, marries private and public. He recounts intersecting stories of O’Connor’s personal and professional trajectories, beginning with her girlhood on the Lazy B Ranch at the Arizona-New Mexico border to her college and law school days at Stanford to her stint in Arizona politics and as a state court judge there and on to her time on the United States Supreme Court. Along the way, he weaves in family milestones, individual challenges, and anecdotes about domestic and social life.

Although standard biographical fare, this blending serves a larger purpose here. As a jurist, O’Connor famously preferred narrow, context-specific solutions to legal problems over definitive and widely applicable rules. One illustration that stands out is the notorious Bush v. Gore, which Thomas describes as “the most difficult and momentous case of her life.” (333) In this highly controversial intervention by the Supreme Court into the 2000 presidential election, O’Connor not only voted with the majority in a per curiam (for the Court) opinion, which halted the Florida recount, thus handing the win to Bush; also, according to Thomas, she authored narrowing language designed to prevent the ruling and its rationale, based on the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause, from ever having any application beyond this specific case: “Our consideration is limited to the present circumstances, for the problem of equal protection in election processes generally presents many complexities.” (332)[4] (Those familiar with the Anglo-American judicial tradition, with its reliance on precedent, appreciate how this disclaimer represented a jarring departure from the usual practice.)

As a jurist, O’Connor famously preferred narrow, context-specific solutions to legal problems over definitive and widely applicable rules. One illustration that stands out is the notorious Bush v. Gore, which Thomas describes as “the most difficult and momentous case of her life.”

This case typifies how O’Connor envisioned her judicial function as one of problem-solving. As she saw it, the contested election results posed a problem requiring a solution. Like all problems, however, this one had its own context and nuances, meriting a narrowly tailored response that would preserve flexibility for the future when new problems calling for different solutions would arise. Thomas explains and the legal literature documents that these hallmarks—nuance, attention to context, limited application, and flexibility (315)—can be found in many cases in which O’Connor played a decisive role, including those on abortion, religion, and affirmative action. Of course, this approach not only earned O’Connor the title of “pragmatist,” but also made her the target of criticism, including especially fierce condemnation by some of her Supreme Court colleagues, who claimed she was just postponing important questions for another day while depriving the lower courts of much-needed guidance.

Consistent with the intimacy promise, Thomas explains how Bush v. Gore also exemplifies the seamless way in which O’Connor’s personal and professional lives intertwined. Precisely because of her vote that made Bush the President, she felt that she could not retire during his first term—despite her plan before the election. (333-34) So, she soldiered on, while feeling pulled to care for her husband whose dementia was worsening; then, she later found herself, perhaps naively, relying on her one-time beau Chief Justice Rehnquist’s insistence that she could retire because he would not, only to learn later that he had not disclosed the extent of his own health problems, which caused his death in office shortly after she stepped down. Thomas explores these crosscurrents while also widening the lens to document how O’Connor’s judicial clerks appreciated that their work with her encompassed so much more than legal research and writing; rather, in the words of one, they were all taking part in “not just an apprenticeship in law but an apprenticeship in life.” (295) This was particularly and poignantly so when, toward the end of her time on the Court, John O’Connor would spend the day in her chambers so she could attend to his needs and comfort him with her presence. (366)

B. Gender

Even if my summary above provides a glimpse of the “intimate portrait” that Thomas seeks to present, it fails to capture explicitly what the most prominent part of the biography’s title communicates, namely O’Connor’s “firstness.” As Thomas suggests, the quotidian aspects of O’Connor’s life, from girlhood on, become especially meaningful because of her pioneering role as the first woman to sit on the United States Supreme Court.

Because O’Connor’s “firstness” projects its shadow on everything, gender necessarily looms large, and yet Thomas’s treatment struck me as thin and unsatisfying. Certainly, Thomas devotes considerable attention to O’Connor’s felt conflicts as wife and mother, her apparent guilt about uprooting her husband from Arizona (375, 378), and her admonitions to her clerks to prioritize their families (209). He also flags her stereotypically female commitment to connectedness and collegiality, with her insistence that the Justices have lunch together regularly (274-75), and he recounts how she warmly welcomed Ruth Bader Ginsburg to the Court in 1993 (286-87). In addition, of course, Thomas highlights O’Connor’s gender jurisprudence, laying out how she decided and wrote opinions in cases about sex discrimination and abortion in particular (278-81, 316-18). Along the way, Thomas takes pains to acknowledge that O’Connor paid especially close attention to the facts of cases when they “involved women and children” (316), and he asserts that “[w]ithout question, her experience as a woman, daughter, wife, mother—and now grandmother—influenced her jurisprudence” (268).

From Thomas’s treatment, O’Connor’s more understated, even skeptical, approach came from the self-reliance she developed on the Lazy B, and it reflected less a matter of strategy than her matter-of-fact way of moving forward in life to pursue the “real-world solutions” that she preferred, both on the Court and off.

Nonetheless, I wanted more. As I read Thomas’s approach, he would pin my dissatisfaction on O’Connor herself and her own conception of gender. Compared to Ginsburg, outspoken foe of sex discrimination and now pop-culture feminist icon as “the notorious RBG,”[5] O’Connor took a more understated approach—although both began their illustrious careers precisely the same way, with the inability to get a law firm job because none would hire a woman, despite their stellar law school records. (285) From Thomas’s treatment, O’Connor’s more understated, even skeptical, approach came from the self-reliance she developed on the Lazy B, and it reflected less a matter of strategy than her matter-of-fact way of moving forward in life to pursue the “real-world solutions” that she preferred, both on the Court and off. (313) Thomas writes, building on quotations from former clerk Kent Syverud about her views of sex and race discrimination: “She disliked victimhood and identity politics. ‘She was very annoyed about the idea of a “woman’s point of view,”’ said Syverud. ‘She had a lot of experience of her own to know that the playing field was not always level, but she disliked explicit recognitions of race.’” (347) So I imagine that Thomas would claim to be just telling it, as they say, like it is and as any other author would have as well.

Yet I detected elisions and oversimplifications that I suspect other authors, especially those more attuned to gender and feminist jurisprudence, might well have avoided. Two examples help make my point. First, although Justice O’Connor is certainly entitled to reject the label “feminist” (267), it would have been easy to note how her pragmatic and context-sensitive approach to deciding cases tracks a methodology that feminist legal theorists call “feminist practical reasoning.”[6] Indeed, Thomas comes so close when he writes: “by judging in her one-case-at-a-time fashion—by looking closely at the facts and broader social context—she did bring a uniquely female perspective: her own.” (268) He could have enriched this analysis with a brief reference to feminist legal methodologies, adding force and complexity to O’Connor’s supposed rejection of the idea that women decide cases differently and her clerks’ reported bewilderment “at her lack of self-awareness.” (268, 351)

Second, the biography includes only the skimpiest mention of O’Connor’s concurring opinion in J.E.B. v. Alabama,[7] when—again—situating it in feminist jurisprudence would have provided a deeper view of the significance of gender to O’Connor. Thomas’s full treatment of the case consists of two sentences:

In a 1994 case ruling that a state criminal court not exclude female jurors, O’Connor wrote: “one need not be a sexist to share the intuition that in certain cases a person’s gender and resulting experience will be relevant to his or her view of the case.” Gender, she declared, should make no difference as a “matter of law”—but that didn’t mean that gender made no difference as a “matter of fact.” (268)

He might have said more, however, especially because this small slice of J.E.B. both seems at odds with the Syverud quotation above about O’Connor’s refusal to embrace a “woman’s point of view” and also reveals subtlety in how O’Connor approached cases about “women and children.” Accordingly, it is worth noting that J.E.B. arose from a criminal prosecution for paternity and child support. The majority held unconstitutional the state’s use of peremptory challenges to strike male jurors (not female jurors as Thomas’s summary claims); O’Connor joined that majority opinion, but she went on to write a separate concurring opinion for herself alone. A leading treatise on feminist legal theory cites the majority’s approach as exemplifying the influence on the law of liberal feminism with its commitment to formally equal treatment.[8] This treatise goes on to observe how O’Connor’s separate concurrence pushed back on formal equality.[9] A longer quotation from that solo opinion offers telling language to supplement Thomas’s abbreviated summary, suggesting that O’Connor shared some ideas characteristic of a different school of feminist thought, namely cultural feminism:[10]

Nor is the value of the peremptory challenge to the litigant diminished when the peremptory is exercised in a gender-based manner. We know that like race, gender matters. A plethora of studies make clear that in rape cases, for example, female jurors are somewhat more likely to vote to convict than male jurors. See R. Hastie, S. Penrod, & N. Pennington, Inside the Jury 140–141 (1983) (collecting and summarizing empirical studies). Moreover, though there have been no similarly definitive studies regarding, for example, sexual harassment, child custody, or spousal or child abuse, one need not be a sexist to share the intuition that in certain cases a person’s gender and resulting life experience will be relevant to his or her view of the case. … Individuals are not expected to ignore as jurors what they know as men—or women.[11]

Of course, authors must make choices, and biographers cannot include every detail. And I certainly do not contend that Thomas should have been writing this book for feminist legal theorists. Nonetheless, these examples helped me in my own effort to make more concrete the nagging sense I had throughout the book that something was missing.

C. Denouement

My incipient skepticism about Thomas’s sensitivity to and appreciation of gender dynamics intensified as I finished reading the text and turned to the acknowledgments, which begin on page 407 with the following paragraph:

My wife Oscie was essential to this book. We conducted almost every interview together, and she spent many hours with me reading documents in Justice O’Connor’s chambers at the Supreme Court and in the Madison Building reading room of the Library of Congress. We talked about the book constantly, and she worked over every word of the manuscript. We traveled together to visit the justice in Phoenix and to speak with Justice O’Connor’s clerks and friends in many places around the country. Oscie has been deeply involved in most of my books as an editor and coresearcher, but this one is different. She understood Justice O’Connor in ways that I could not. The portrait here is the work of two people who have grown ever closer over the years. It is a joint project and a labor of love. (407)

True, on one reading, this paragraph might assure readers that, thanks to Thomas’s close collaboration with his wife, a “woman’s point of view” informed the book, despite O’Connor’s claimed rejection of such perspective. This understanding brings to mind how Washington University’s famous sex researcher William Masters succeeded in incorporating women’s interests and bringing women subjects into his studies, thanks to his collaboration with Virginia Johnson, who later became his wife.[12]

Yet, for me, this paragraph stood out as a red flag, prompting a more mistrustful reaction—although I know nothing about the relationship of Thomas and his wife, beyond what he writes here, and I have no sense of her preferences. I found the paragraph both deeply heartfelt and shockingly myopic, raising several questions: Why does not the book’s authorship include both names or at least say “Evan Thomas with Oscie ___”? (We do not even learn her full name.) After all, William Masters gave Virginia Johnson coauthor credit for their books and they became known as a team: “Masters and Johnson.”[13] Why did Thomas wait until more than 400 pages to acquaint readers with his wife’s significant role?

By the end, the book left me puzzling over several questions about the author, diverting attention from the Justice herself: How reliable a narrator is Thomas in telling her story? How did Thomas’s own intimate relationship color his “intimate portrait”?

Try as I might, after reading this belated disclosure, I could not help thinking of two recent films, The Wife, the fictional story of a husband who receives the Nobel Prize in Literature for work secretly authored by his wife,[14] and Colette, a historical drama about the French novelist who began her career as a ghostwriter for her domineering husband, a pretender who achieved success based on her unacknowledged talents and labor.[15] These comparisons are no doubt too harsh, and a more apt and forgiving recent-film reference might be Life Itself, in which the “unreliable narrator” operates as a plot device.[16]

By the end, the book left me puzzling over several questions about the author, diverting attention from the Justice herself: How reliable a narrator is Thomas in telling her story? How did Thomas’s own intimate relationship color his “intimate portrait”? How confident can readers feel that Thomas captured and presented a full picture of O’Connor, especially when it comes to how gender and society’s construction of it shaped her and her history-making life?

Author’s note: I wish to thank colleagues Adrienne Davis and Rebecca Hollander-Blumoff for their valuable comments on an earlier draft of this book review.