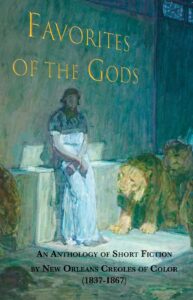

Favorites of the Gods: An Anthology of Short Fiction by New Orleans Creoles of Color (1837-1867) by Chris Michaelides is among the most recent offering from Les Éditions Tintamarre. For over twenty-five years the press has been devoted to reprinting the considerable literary legacy of Louisiana’s writers in French. The several dozen texts now available include the novels and poetry of the golden age of the mid-nineteenth century up to Francophone poetry by contemporary writers. The nineteenth-century collection includes work by French émigré writers as well as that of Louisiana’s Creoles and Creoles of color. In particular and despite the obstacles against them, les gens de couleur libres were prolific. Favorites of the Gods is a collection of short fiction by seven accomplished Creoles of color, among them, Victor Séjour, Armand Lanusse and Michel Séligny. In 1843, Armand Lanusse created the journal L’Album littéraire, which included poetry and short fiction. Lanusse also produced one of the foundational texts of American literature. In 1845, he edited and published, Les Cenelles: Choix de poésies indigènes, the first such anthology by Americans of color; in addition to reprinting such canonical texts, Éditions Tintamarre also published an anthology of short fiction that originally appeared in nineteenth-century journals or newspapers. Parole D’Honneur: écrits de Créoles de couleur néo-orleanais, 1837-1872 published in 2004 and edited by Chris Michaelides, made this work available to readers of French for the first time in over one-hundred years. Favorites of the Gods includes seven of the stories from Parole D’Honneur in English translation, vastly expanding its audience. The two collections are a gift to students, scholars and general readers interested in Francophone Louisiana’s contribution to American literature.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, publishing in the Crescent City became increasingly dangerous. In 1830, the state enacted laws, aimed at Creoles of color, prohibiting the publication of anything conducive to social unrest. Not until the creation of La Tribune de la Nouvelle Orléans, did Creoles of color have more than limited access to this public forum. When brothers Dr. Louis-Charles and Jean Roudanez founded La Tribune de la Nouvelle Orléans in 1864, it became the first American daily newspaper owned and operated by free men of color. Of the fiction in Favorites of the Gods, three of the short stories and the one novella were published in La Tribune in 1865. The earliest short story was first published in a journal in France and two others appeared in L’Album littéaire. The volume is organized chronologically to suggest a progression in theme and tone between the 1837 when Victor Séjour’s incendiary abolitionist story “The Mulatto” appeared, to Joanni Questy’s “Monsieur Paul,” published in La Tribune in 1867.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, publishing in the Crescent City became increasingly dangerous. In 1830, the state enacted laws, aimed at Creoles of color, prohibiting the publication of anything conducive to social unrest.

In the introduction to Favorites of the Gods, Michaelides foregrounds this timeline linking each story to important economic and political pressures on the Creoles of color community. Across the thirty-year span, the stories are connected formally and thematically. Formally the influence of the period’s most popular genre, melodramatic theater, is everywhere. From Séjour’s boisterous knife-wielding bandits or Lanusse’s abandoned placée Marie, who throws herself under the carriage of her husband and his White wife, passions possess and consume these characters. Thematically, these stories are inhabited by orphans in search of recognition, legitimacy and family. Set in the strongly patriarchal society of the mid-nineteenth century, the missing father might be the White slave owner who refuses to recognize his son (Séjour) or the White man who cannot marry his Black mistress because interracial marriage is against the law (Questy). In Adolphe Duhart’s “Three Loves,” the father has died leaving two daughters, one by his wife and one by his mistress, a woman of color. White patriarchy is subverted when his “legitimate” daughter dies, leaving her financé no choice but to marry her darker sister. In addition to the death of the Old World order, the overwhelming presence of orphans throughout these stories also reflects the reality of life in mid-nineteenth century. Many died from yellow fever, smallpox, tuberculosis, gangrene, or in combat or by suicide. In Joseph-Colastin Rousseau’s “Flowers for the Grave,” Robert loses his parents and his sisters to illnesses. This story mirrors “Three Loves” in that Robert is raised with a slightly older, darker sibling, Charles, who may be his half-brother and behaves like a jealous lover. The drive in each narrative is to make whole that which has been broken by death.

The beautifully written “An Orphan Girl” by Michel Séligny gives the orphan theme an uplifting spin. It opens with a triptych of images of women. Two of the images are paintings and the third is Séligny’s character Solange, who embodies the attributes of the first image, “serenity and spiritual contentment” even though she was orphaned as a child and might have become the second image, “an orphan dressed in mourning…so alone.” Solange and her husband Edgar are orphans of French émigrés; their fathers died in battle and their mothers of disease. Their status as orphans links them to the Creoles of color in that they do not have full access to the legitimacy that family confers because their extended family is in France. And for Creoles of color, the White father’s recognition could provide his mixed-race children a legitimacy that was limited.1

In addition to the death of the Old World order, the overwhelming presence of orphans throughout these stories also reflects the reality of life in mid-nineteenth century. Many died from yellow fever, smallpox, tuberculosis, gangrene, or in combat or by suicide.

Of the early stories, “The Mulatto,” and “A Marriage of Conscience” stand out for the explicit criticism of the slave society. “The Mulatto” is a passionate condemnation of slavery because it corrupts familial bonds. The “mulatto” Georges’ search for legitimacy is tied to knowing his father’s identity. So, when Georges realizes that the cruel master he has killed to avenge his wife’s death, is his own father, he kills himself. Séjour used the plot to underscore just how the denial of familial bonds will destroy the entire family, Black and White.

Armand Lanusse’s “A Marriage of Conscience” criticizes plaçage (the practice of “placing” young women of color with rich White men to be concubines) with brilliant economy. The young victim, Marie, enters an almost empty cathedral, kneels at the alter of the Virgin Mary, to confesses her putative sins. Her mother had persuaded her to accept the proposed marriage which was then performed by a priest. In this thoroughly corrupt society, the institutions of the church and family have sanctioned a marriage that neither the government nor the White “husband” are legally obliged to honor.

Favorites of the Gods includes seven of the stories from Parole D’Honneur in English translation, vastly expanding its audience. The two collections are a gift to students, scholars and general readers interested in Francophone Louisiana’s contribution to American literature.

Favorites of the Gods is a solid collection of short fiction from Louisiana’s Creoles of color written during the most chaotic and perilous decades of the nineteenth century. This collection gives contemporary readers access to these short stories for the first time in English. Chris Michaelides’s introduction provides important historical context for each story. For example, it is helpful to know that among many other pressures afflicting the Francophone community of New Orleans was the influx of English-speaking immigrants from the North and Ireland. Among its consequences was a challenge to the cultural dominance of French language and culture in the City. The schism within the Catholic Church Lanusse alludes to in “A Marriage of Conscience” is connected to the emergence of a rival congregation of Anglophone Catholics. Such details provide us a glimpse of the world in which the stories were written. And yet, the literature itself has a history well worth knowing.

Victor Séjour’s “The Mulatto” is the first short story published by an American of African descent. It has been translated twice before; first in 1997 by Philip Barnard for the inaugural edition of the Norton Anthology of African American Literature, and again in 2000 by the African American writer Andrea Lee, for The Multilingual Anthology of American Literature. And although Lanusse refers to the schism in “A Marriage of Conscience,” in a discussion of this literature, it is as important to know that he wrote a satirical poem, “Epigramme” on the same theme. “Epigramme” was published two years after “A Marriage” in Les Cenelles. As a theme plaçage engaged his imagination enough to address it in two different literary forms. “Epigramme” was translated into English by African American scholar of Romance Languages, Mercer Cook and in 1958, Langston Hughes included his own translation of the poem in The Langston Hughes Reader. Favorites of the Gods is a welcomed addition to Éditions Tintamarre’s rich collection.