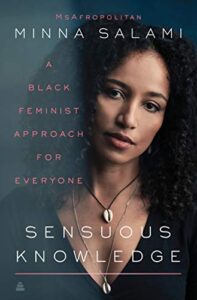

Minna Salami’s Sensuous Knowledge: A Black Feminist Approach for Everyone is about gnosis, the Greek word for knowledge. The essence of this well-crafted, highly engaging, and readable text is that African women are the persons that should be centered as foundational to where societies form knowledge. This is especially true if societies aspire to be just and humane. Salami is correct.

The data on women throughout the African continent is shockingly disparate. Women throughout the continent face taxing conditions to say the least. Women throughout the continent overall are statistically at the bottom of all economic indices. How economic data are derived is also indicative overall of how little the status of women is valued as essential to the labor force and the agrarian economies that sustain the various regions on the continent. So, from the outset, let me say Salami is right in her determination to change how knowledge is assessed as she asks who, what and how we filter knowledge that leaves African women out of moral considerations or social recognition.

In Zora Neale Hurston’s 1937 classic novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, Nannie, the grandmother of the novel’s protagonist Janie, sums up the value of African women:

Honey, de white man is de ruler of everything as fur as Ah been able tuh find out. Maybe it’s some place way off in de ocean where de black man is in power, but we don’t know nothin’ but what we see. So de white man throw down de load and tell de nigger man tuh pick it up. He pick it up because he have to, but he don’t tote it. He hand it to his womenfolks. De nigger woman is de mule uh de world so fur as Ah can see. Ah been prayin’ fuh it tuh be different wid you. Lawd, Lawd, Lawd! (14)

Hurston’s character Nannie could not change the world she inhabited but she understood its cruelties with an unsentimental calculus. This is why Salami makes it her mission to recenter the perspective from which we see the world to build a broader knowledge base out of the experiences of Black women in order to remake our understanding of the world.

While I do not dispute her claim that feminism requires a change of mind, her analysis begs the question what kind of institutional change must occur for the kind of feminism she extolls.

The lens is which we filter reality, she argues, is through “Europatriarchal Knowledge.” Salami writes that at the heart of this knowledge is dualism. “Stories turn into knowledge,” she offers “and knowledge transforms into matter. The dualist worldview separates matter from story, but narrative is the matter from which we build our worldview, which in turn becomes physical objects: books, buildings, borders, and so on.” (13) Ironically, she borrows from the British seventeenth-century poet, government official and author of Paradise Lost, John Milton, whose writing is a part of the Western literary canon that Salami is challenging. Milton was at the center of a power structure that exercised imperial rule over Ireland and overtook the Portuguese as the most plutocratic purveyors of slavery over the centuries of the Atlantic slave trade. This is not to discredit Salami’s point. What she learns from Milton is that “Sensuous Knowledge is thus a poetic approach; it is the marriage of emotional intelligence with intellectual skill. . .. Sensuous Knowledge is knowledge that infuses the mind and body with aliveness leaving its impact behind like the wake of perfume. . . . Sensuous knowledge means pursuing knowledge for elevation and progress rather than out of an appetite for power.” (15)

And I could not agree more! Opening the mind, as well as the heart is essential to the kind of social change that lifts up what the philosopher Martha C. Nussbaum calls the human capabilities in her 1999 book Women and Human Development. A decolonial mental process is a gentle reorientation, Salami says. She writes, “Decolonization of the mind should instead cause a sense of unity and calm in the mind. It is not removing thought patterns by force but instead gently inserting new insights, which eventually reshuffle and do away with harmful thoughts.”(71) The feminism she seeks requires reinvention away from the totalization of patriarchal thought and behavior that believe in male supremacy. While I do not dispute her claim that feminism requires a change of mind, her analysis begs the question what kind of institutional change must occur for the kind of feminism she extolls. Surely, Salami recognizes that “Europatriarchy” is rooted in a kind of misogyny that is derivative of “the giant triplet of racism, economic exploitation, and militarism” as Martin Luther King, Jr. insightfully analyzed over fifty years ago.

Without a political philosophy that underlies her writing, it is only beautiful poetry left to the devices of those who wish to control the apparatuses of state power.

This raises a further question for me. If a feminism is going to be revolutionary as a form of thought and practice it cannot address women alone. What does an everyday feminism have to say to Black and African men? Salami shares a horrific story of being drugged at a club and ganged raped by African emigre men in London. As she regained her senses and attempted to find her clothes these men were watching football (soccer) as though nothing occurred. (120) It is a truly disturbing tale that forced me to put the book down for a few days. This violent act magnifies institutional questions and concerns about what allows males to think that violence against any woman, especially women of African descent, is an acceptable norm. Institutional guardianship must always be about building human capabilities, if they are not, we are all in trouble. The institutions that we set up to protect one another will simply reinforce the violence of misandry, misogyny, and rapacious behavior towards children, men, and women. It will be the way of the world, that is, what is too often referred to as the “natural” order. An everyday Black feminist approach that everyone can follow must enjoin a robust institutional analysis of the establishments that currently support Black and African lives and talk to Black men.

It is not as though Salami does not touch on institutional realities. She does. She writes of Nigeria where she was partly reared “[w]e need cultural monuments, museums that weave the legacy of slavery and colonialism into the mythology. Our collective imagination should be shaped by cultural interventions that express the confluence of ambitions that created Nigeria.” (94) The problem is she does not tell us how this might occur. Without a political philosophy that underlies her writing, it is only beautiful poetry left to the devices of those who wish to control the apparatuses of state power. If Africans and women of African descent need anything it is their own version of political liberalism that speaks to Black and African men too.

I am delighted to have read Salami’s book because there are so many great insights to be gathered from her and I am all the better for having read it because of its challenges to my own knowledge base. Yet, I wish she had spent more reflection on how to institutionalize her rich gnosis.

Salami’s book, as she acknowledges, owes a debt to the late bell hooks (Gloria Watkins). Like hooks’ work this book comes from a place of deep pain, thoughtfulness, and engagement. I am delighted to have read Salami’s book because there are so many great insights to be gathered from her and I am all the better for having read it because of its challenges to my own knowledge base. Yet, I wish she had spent more reflection on how to institutionalize her rich gnosis. I was reminded of Elaine Pagel’s examination of the Gnostic Gospels. Pagel offers that what kept Christianity alive in a fight between “Gnosticism” and “Orthodoxy” was who ultimately controlled the ecclesiastical or the institutional apparatus of early Christianity. Pagel’s insights from the ancient world are clear-eyed: we must build institutions in the struggle and politics of institutional building of human capabilities in democratic societies. While poetry or sensuous knowledge allows us to imagine and expand the boundary of the self and society, it is the actual political structures that must secure those dreams to ensure our right to breathe and to live.