We were seated at a small wooden table in a corner of Big Sleep Books in the Central West End. John Lutz was the star of the book signing that Saturday afternoon in 1992, he with his twenty-eighth mystery novel and me with my first book. Dozens of readers flocked to him. A few loyal friends dropped by for me. Lutz acted as though we were equal. That was just the way he was, comfortable in his own skin, unpretentious, and generous in a competitive business.

During a lull in sales, he turned to me, and in his deep radio announcer voice, asked, “Do you know what’s the most important trait for an author?”

“Curiosity,” I said, thinking how he plumbed his characters’ psyches.

“Persistence,” he said, looking me in the eye. “Writing has a rejection rate second only to acting. The rejection is part of the process. You just keep doing it. Every writer has at least one unsold novel.”

During a lull in sales, he turned to me, and in his deep radio announcer voice, asked, “Do you know what’s the most important trait for an author?”

He stopped to sign his latest mystery for a lawyer bent on becoming the next John Grisham. As the man left, Lutz said, “I know a lot of attorneys who want to be writers. I don’t know a single writer who wants to practice law.”

He had known what he wanted to do since he was thirteen years old. One summer day, sitting on the porch of his parents’ home on Ethel Avenue, he read Ray Bradbury’s short story “A Sound of Thunder” in Collier’s magazine. That changed his life. “I realized words were more than simply conveying information,” he said. “I wondered if I could be a storyteller, too.”¹

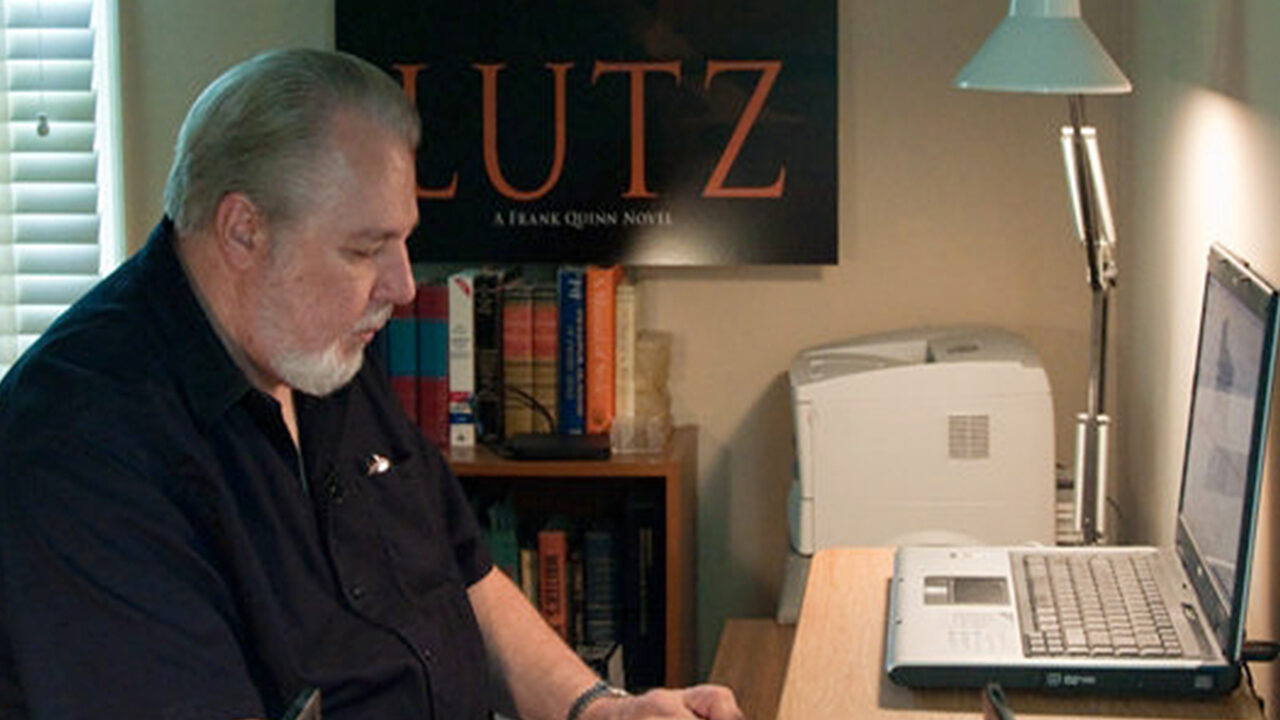

Over his fifty-three-year career, Lutz published at least fifty books and some two hundred and fifty short stories. He grew fluent in any type of crime and mystery writing—private eye, suspense, police procedural, espionage, and thriller. His popular detective series featured Al Nudger in St. Louis, Fred Carver in Del Moray, Florida, and Frank Quinn tracking serial killers in Manhattan.

He won the coveted Edgar Mystery Award, two Shamus Awards, and the Private Eye Writers of America Life Achievement Award. He served as president of the Mystery Writers of America and Private Eye Writers of America. When he was honored at the national Boucheron convention for mystery and detective authors, he seemed uncomfortable being the bride at the wedding. “He disliked a lot of attention,” says his wife Barbara Lutz. “He’d rather be holed up in the basement at home writing.”

Lutz achieved his goals without an MFA, an MA, or even a college degree. An autodidact, he devoured libraries. When I told him I had enjoyed Nella Larsen’s Passing, he recommended William Faulkner’s Light in August and Philip Roth’s The Human Stain. When I thanked him, he said, “Most writers serve apprenticeships by continuously reading.”

“Rejection doesn’t stop you as a writer,” he once told me. “Over time, those editors became encouraging.” His wife said, “One editor penciled a note in the margins, saying he was close to being published. That was like gold to John.”

His success was a long time coming. He drove a truck as a Teamster for the old Bettendorf-Rapp grocery stores and polished his craft in his free time. He spent seven years opening some thirty stamped, self-addressed envelopes to read form rejection letters inside.

“Rejection doesn’t stop you as a writer,” he once told me. “Over time, those editors became encouraging.” His wife said, “One editor penciled a note in the margins, saying he was close to being published. That was like gold to John.”

He debuted his first short story, in 1966, “Thieves’ Honor,” in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine magazine. Over the next five years, Lutz wrote more for that magazine, and also Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. They did not pay enough to support a family with three children, so he turned to crafting books and his wife worked at her career. “The best friend a writer can have is a working spouse,” Lutz joked. He published his first book, a thriller, The Truth of the Matter, in 1971.

Readers snapped up his police procedurals because they could tell he knew the details of police work. As a switchboard operator for St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department, he had listened to beat cops phoning in from call boxes. “That gave me insight into how they think,” he told me. “Police think they are aware of a depth of the dark side of human nature that other people can’t begin to imagine. And that’s largely true. It’s very difficult to be a good cop.” ²

Clement Igel of Chesterfield, who bought more than forty of Lutz’s books and rereads them, says, “I appreciate how observant John was of human nature.” He points out in one Nudger book, Lutz writes, “Integrity is like a lost button. You never know where it’ll show up.”

Despite his accolades and bigger book contracts with foreign rights, the Lutzes lived conservatively in a comfortable home in Webster Groves. “When you have a Cadillac year, you buy a Chevy,” he told me.

The Man Who Truly Understood Women

The movie money arrived in the ’90s. His stand-alone novel SWF Seeks Same became the big-screen hit Single White Female, and HBO later featured his The Ex. “If you stay in this business long enough, eventually someone overpays you,” he joked.

Both films center on women’s issues: SWF delves into the sociopathy of a roommate and The Ex deals with a disturbed former wife battling the second wife.

Lutz was a man who understood women. Growing up sandwiched between two sisters, marrying young, and raising two daughters (and a son) helped him create very real female characters. “If you want to understand women, bring up girls,” he said. “I observe women, listen to the details of their intimate conversations, and, like most writers, analyze people. I’m always observing and taking mental notes. Like a cop armed with a gun, I’m always on duty with a pencil.” ³

He and Barbara first met when they were both seventeen, working at the old Tivoli Theater in Clayton, John as an usher and petite, pretty Barbara as the candy girl. Two years later, they married, in 1958. He once joked, “I’ve been married so long I think all women have appendectomy scars and am surprised at pool parties when they don’t.” Theirs was a happy marriage.

No alpha readers, no beta readers for him. He did not show his work until it was complete, and then only to [his wife] Barbara or one friend. Many literary agents today edit their clients’ work. Lutz did not need it.

Is there a common theme to Lutz’s books? I asked Barbara. “Spousal murder,” she said, laughing. “He had fun with it. He even based one character, a prostitute, on my mother. We all laughed about it. She adored him.”

Once their three children were grown, John and Barbara went out to breakfast every day and returned home where he wrote for three to four hours, six days a week. “He worked solidly every day,” says his agent of nearly forty years, Dominick Abel. “Even when unfortunate things happened like the death of a daughter.” When authors are portrayed in fiction, they often live a bohemian, drunken lifestyle, as in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. Real writers are very self-disciplined, Lutz said. “I just clock in and clock out five, six days a week, and miraculously I get paid,” he told me. “I enjoy it as much as I did when I began. It’s the writing I enjoy and not so much having the book come out.” He published two books a year.

No alpha readers, no beta readers for him. He did not show his work until it was complete, and then only to Barbara or one friend. Many literary agents today edit their clients’ work. Lutz did not need it. “He wrote very cleanly. He was careful to get things right,” says Abel. “He was a true professional who made sure to deliver. He was very proud of his books but never boastful.

“John was a very regular guy. Consistent. Relatable. He had a terrific sense of humor,” says Abel.

At one signing at Left Bank Books, Lutz chuckled to himself reading a passage in which the mother of a detective pressures her daughter to get married. “I wrote this part for pacing, to stall the action,” he said. The women in the audience laughed. You could tell he enjoyed his characters. “He was very respectful of them,” says Abel.

“He wrote to tell a story not to shock,” his agent says. There was no excessive violence. He wrote it only to reveal the character of his serial killers, Abel points out.

For the last eight years of his life, Lutz suffered from Lewy Body dementia with Parkinson’s symptoms. “He was so smart the doctors initially didn’t think anything was wrong,” Barbara said. “So I did a lot of research.” Despite his cognitive problems, Lutz continued writing and published his last work, a thriller-spy story, “The Havana Game,” in 2019.

Barbara was with John when he died from Covid-19 before dawn on January 9 at his nursing home in Chesterfield. He was 81.

“He will be missed dearly in the St. Louis literary world,” says Shane Mullen, event coordinator at Left Bank Books. “He was so convivial with the signing line. And Barbara would be there handing out red ribbons to use as bookmarks for her husband’s latest mystery.”