To the contemporary casual observer of sports history, Joe Frazier was little more than a foil for Muhammad Ali: the opponent whom the brash Ali famously (and repeatedly) called a “gorilla” in the lead up to their third and most notable fight, the “Thrilla in Manila.” This is hardly Frazier’s fault: few athletes—in the 1960s and ’70s, before, or since—have shined as brightly as the political activist and icon Ali, once known as the “Louisville Lip” for his talent at self-promotion via the taunting of his opponents.

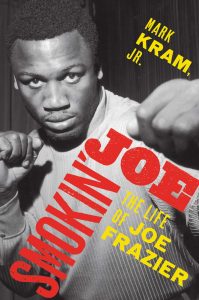

But Joe Frazier deserves more than a lurking presence in Ali’s shadow, and he knew it. As Mark Kram Jr. puts it in his new biography, Smokin’ Joe: The Life of Joe Frazier, “the antipathy he harbored for Ali simmered just below a boil” even to the end of his life. Though friends advised Frazier against it, he “could not help himself from battering his erstwhile rival with verbal haymakers,” pointing out Ali’s infirmity in old age (which due to advanced Parkinson’s disease was worse, at least outwardly, than Frazier’s own debilitation) and suggesting, as Kram puts it, “that his signature was embossed on the physical wreck Ali had become.”

Mean-spirited though this late-life treatment of Ali may have been, Kram Jr. is careful to point out that it was out of character for the often generous and kind-hearted Frazier. He was known around his adopted hometown of Philadelphia for helping stranded motorists, giving to the homeless and food insecure, and otherwise letting “the love” (Frazier’s own term for money) slip from his hands and into those of the less fortunate. Frazier himself had come up from poverty in South Carolina to Philadelphia, ultimately avoiding trouble and finding purpose—like so many famous pugilists—in the male-bonding space of the boxing gym. Frazier’s rise was meteoric: he was first noticed in Philly’s Twenty-Third Police Athletic League gym in North Philadelphia (known as the “Twenty Third PAL”) in 1962. By 1964 he was the gold medalist at the Olympic Games in Tokyo. It would take six more years for Frazier to become Heavyweight Champion of the world, however, primarily because of Ali, who threw the heavyweight division into chaos when he refused induction into the U.S. armed forces during the Vietnam War and was stripped of his titles. And when Frazier did win the heavyweight championship, in 1970, the still-banned Ali was quick to question its legitimacy. Only when the two fighters actually met in the ring, first in 1971 (won by Frazier), then again in ’74 (won by Ali) and ’75 (another Ali win, this time in the aforementioned “Thrilla”), did Frazier have a chance to set the record straight, and even there he was mostly outmaneuvered by his rival.

Mean-spirited though this late-life treatment of Ali may have been, Kram Jr. is careful to point out that it was out of character for the often generous and kind-hearted Frazier. He was known around his adopted hometown of Philadelphia for helping stranded motorists, giving to the homeless and food insecure, and otherwise letting “the love” (Frazier’s own term for money) slip from his hands and into those of the less fortunate.

Detailed accounts of the three duels are abundant, from some of the most famous writers of the era—Norman Mailer, George Plimpton, and Hunter S. Thompson among them—and Kram Jr. synthesizes them largely without comment in forging his own history. But there is one famous scribe whose writing about the two great pugilists he cannot leave unmarked: his own father, Mark Kram Sr. The elder Kram covered boxing for Sports Illustrated, Playboy, and Esquire, and authored the 2002 book, Ghosts of Manila: The Fateful Blood Feud Between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, often considered a definitive account. Kram Jr., who followed in his father’s footsteps by becoming a sportswriter, mentions him by name only twice, but his presence lingers throughout. Kram Jr.’s very access to interview Frazier—which provides him an illuminating glimpse into the Champ’s late-life domestic partnership with his longtime assistant (and romantic beau), Denise Menz—was made possible by the elder Kram’s connections. The younger Kram is not tortured by his father’s formidable presence to the extent Frazier was by Ali, but in his 2015 New York Times remembrance, “Bearing My Father’s Byline,” he more or less admits to feeling as though he can never escape the elder man’s shadow. In Smokin’ Joe Kram Jr. recalls his father composing his Sports Illustrated story about the 1974 fight between Frazier and Jerry Quarry, “thinking as the room became clouded with smoke that he attacked the keys with the same gusto with which Joe had imposed himself upon Quarry.” One gets the sense that the younger Kram, like Quarry, or Frazier when dealing with Ali, feels obscured.

One might also extend the underdog ethos (and occasional simmering resentment) that permeates the book outward from Frazier (and Kram Jr.) to include the city of Philadelphia itself, which gets significant attention in Smokin’ Joe. In particular, Kram Jr. explores the tensions between the city’s African-American population and the working-class ethnic whites who began, as a voting bloc, to dominate city politics. Primarily he does this by detailing the relationship between Frazier and Frank Rizzo, who, first as police commissioner and then as mayor, was notorious for a hard-nosed, chip-on-the-shoulder mentality that seemed to manifest itself via antagonism toward Philadelphia’s black community. Despite Frazier’s connections within that community—his gym on the north side of the city was a local pillar of social interaction—he liked Rizzo and Rizzo him. Per Kram Jr., “Frazier would not or could not see beyond the avuncular charm of Rizzo, who presided over a police force that was held in widespread scorn for its brutality.” As a general habit, Frazier tended to align himself with law-and-order politicians, Richard Nixon among them, but it was his friendship with Rizzo in particular that led black Philadelphians like former Tuskegee airman and Philadelphia Daily News scribe Chuck Stone to assert that “Joe Frazier knowingly made his choice and the black community will never let him forget it.”

One might also extend the underdog ethos (and occasional simmering resentment) that permeates the book outward from Frazier (and Kram Jr.) to include the city of Philadelphia itself, which gets significant attention in Smokin’ Joe. In particular, Kram Jr. explores the tensions between the city’s African-American population and the working-class ethnic whites who began, as a voting bloc, to dominate city politics.

One of the ways in which black Philadelphians did not let Frazier forget it was in their often vocal support of Ali. And when the then-Chicago-based Louisville native moved to Philadelphia in 1970, the tension between the two men was amplified. In February of 1971, just more than two weeks from his first bout with Ali, Frazier attended another boxing match “only blocks from his gym on North Broad Street” and “found himself swallowed up in boos as the crowd began chanting ‘ALI, ALI, ALI!’” Though Frazier was quick to dismiss the insult and defeated Ali in the subsequent “Fight of the Century,” the psychic wound lingered, then festered, as the two heavyweights continued to face off in the press (including an impromptu wrestling match on Howard Cosell’s ABC TV show in 1974) and in the two epic fights that would follow. Of their increasingly poisonous verbal barbs in 1975—in which Ali “continued to savage Frazier as apelike in appearance and intellect” and Frazier responded by calling Ali “by his slave name,” Cassius Clay—Kram Jr. asserts that the two crassly manipulated the language of the “subhuman” to incite the other. Yet while Ali metaphorically winked at his opponent, justifying the racist rhetoric as a means of ginning up interest in the fight, Frazier “seethed inside.”

After the “Thrilla in Manila”—which Frazier lost when his cornerman, Eddie Futch, would not let him come out for the fifteenth round, despite the fact that there was some question as to whether Ali could go on himself— Frazier was increasingly bothered by an eye injury and withdrew from the ring, taking on just two more bouts. He turned his focus to his band, “Joe Frazier and the Knockouts,” as well as the management (and occasional mismanagement) of the boxing careers of his sons—none of whom came close to matching the brawling ferocity and formidable skill of their famous father. Recapping the champ’s many family connections and complex web of romantic relationships with little overt judgment, Kram Jr. depicts the champ as attempting to do right by his kin, spread widely though they may be, and finding stability along with no small measure of happiness in his late-life domestic arrangement with Denise Menz, despite his fortune having evaporated.

After several such anecdotes, Kram Jr. finally offers a conciliatory tableau of Ali and Frazier, united at a private dinner in Ali’s hotel suite the night before the 2002 NBA All-Star game. The two men exchange playful verbal jabs over their plates and Frazier offers a prayer for the health of his long-time rival. Finally, Kram Jr. describes Ali whispering to Frazier; “We’re still two bad brothers, aren’t we?” To which Frazier responds: “Yes, we are, man. Yes we are.”

But the book closes where it begins, with Frazier spitting fire at the infirm Ali, rebuffing press-proffered olive branches with commands to “tell [Ali] to take that apology and shove it up his ass.” After several such anecdotes, Kram Jr. finally offers a conciliatory tableau of Ali and Frazier, united at a private dinner in Ali’s hotel suite the night before the 2002 NBA All-Star game. The two men exchange playful verbal jabs over their plates and Frazier offers a prayer for the health of his long-time rival. Finally, Kram Jr. describes Ali whispering to Frazier; “We’re still two bad brothers, aren’t we?” To which Frazier responds: “Yes, we are, man. Yes we are.” The effect is cathartic and heartwarming: a nice bow to tie off the narrative. But it still binds Frazier to Ali, a fate he never wanted and one Smokin’ Joe, as a whole, does its best to resist. Probably it is not possible to encapsulate Frazier without invoking Ali, just as Mark Kram Jr. recalls his father at every mention of his own name. And even if he ultimately fails to do so, Kram Jr’s is a worthy effort at individuating “Smokin’ Joe,” and one that showcases the author’s own formidable writing talents—no matter how fated he himself may be to linger in another man’s shadow.