In Titian’s masterpiece Ecce Homo, Jesus stands, grimed with sweat, ropes cutting into his wrists, at the side of a Pontius Pilate whose robes are trimmed in ermine. The portrait is luminous, the story it tells complete. But now, thanks to sophisticated imaging technology, we can also see the picture that lies beneath that image, upside down and carefully painted over: a man with a heavy mustache and knowing eyes, clutching a quill pen.

I look closely, not because I care about the dude with the mustache but because his presence reminds me of family secrets. People have been telling me these secrets, and I am not sure what to make of them: are they acts of protection and dignity or shame and deceit? When is a secret a kindness, and when is it an unforgivable betrayal? Most secrets fall somewhere in the middle, their urgency and mortification faded by time. Later generations, safely removed from the scandal but haunted by historical gaps, do the detective work and make their peace with the results.

Well-intended reversals, these secrets invert, omit, and alter, carefully covering up the past in the naïve belief that it will remain hidden forever. Titian was probably just being thrifty, saving on canvas after botching a different painting. But in families, cover-ups cause invisible damage, spreading shame to the innocent or refusing to trust them with the truth. Almost inevitably—whether in a year or a century—the secret will be lit up by some new discovery. And then what happens?

People have been telling me these secrets, and I am not sure what to make of them: are they acts of protection and dignity or shame and deceit? When is a secret a kindness, and when is it an unforgivable betrayal?

Less than you might think. Some guy is underneath Ecce Homo, so what? A relative had an affair three generations ago? The revelations might rock your world, but you soon realize that the same ground is still beneath your feet. The real damage was done long ago—by the secrecy, not the secret.

I. Playing detective

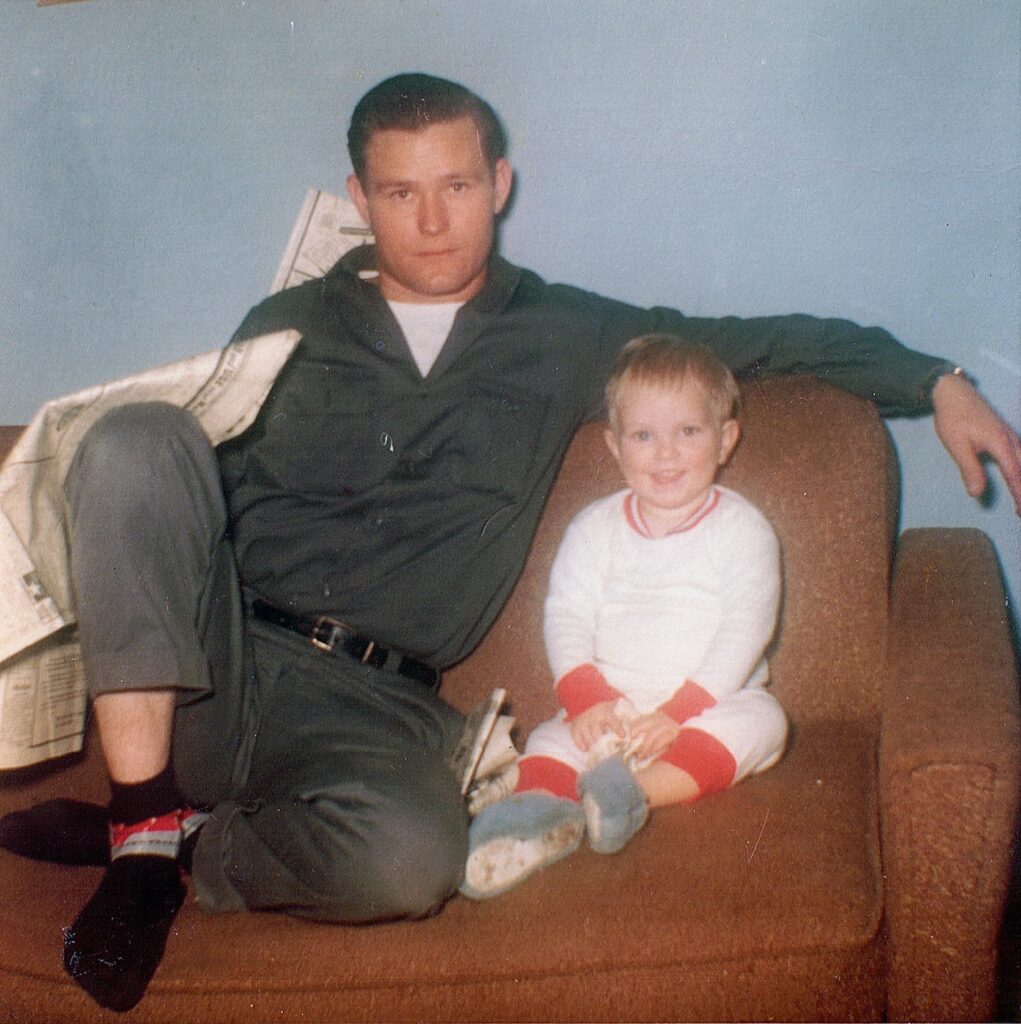

Rodney Wilson with his father, Charles Wilson. (Photo courtesy of Rodney Wilson)

What first sparked my curiosity about family secrets was a note from Rodney Wilson, a history professor who hated history until he began, as a teenager, digging into his own family’s past. His dad had been told that his father, Elsworth Wilson, took his stepfather’s surname, but his biological father was his mother’s first husband, Homer Gilbert. A gentle, do not-rock-the-boat sort, Rodney’s dad just nodded; questions, he had learned, made people uncomfortable.

Rodney took after his mom: he questioned everything. He wanted to know more about this Homer guy, his great-grandfather. He had married Rodney’s great-grandmother, Bertha Aubuchon, in 1909, and Elsworth had been born three years later. But the marriage was shaky from the start, and by 1910, both Bertha and Homer had returned to their parents’ homes to live.

Rodney went to drink tea with his aunt Imogene, his father’s sister. She said the Aubuchons had taken Homer in for some reason; that was how he and Bertha met. But the family later kicked him out, and then Bertha did, too.

Homer never married again. A foreman at Union Starch & Refining Company, he spent his evenings drinking Stag beer and listening to the ball game. His niece and two cousins were still living, and they agreed to a DNA test. None of their DNA matched up with Rodney’s.

Secrets detonate after the players are gone, leaving the most intriguing questions unanswered.

Homer was not his great-grandfather. So who was? The stepfather, maybe, and the marriage just came later? Rodney found Wilson relatives and asked them to test. No paternal overlap. Rodney was out of theories. Casting about, he did a Y-DNA test to find surnames of males with the same Y DNA. Five matches came back: three “Lynde,” one “Lyndes,” and one just the letter “L.”

The only “Lynde” anybody in Rodney’s family had ever heard of was Paul Lynde, the cut-up on the old game show Hollywood Squares.

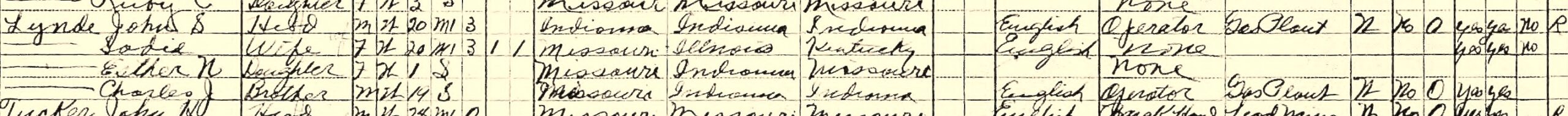

Combing through the 1910 census, Rodney found a Lynde family living in Flat River, Missouri, where Bertha lived at the time. He dug up an old Sanborn insurance map and located her address. The Lynde family home was five minutes away, halfway between Bertha’s family home and Homer’s. A Charles Lynde, age nineteen, lived there with his parents. Tall, with brown hair and blue eyes, he could read and write English, and he had a steady job at a gas plant.

A cross-section from a copy of the Lynde family census (Courtesy of Rodney Wilson)

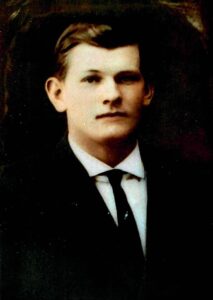

Was he Rodney’s great-grandfather? Rodney found one of his relatives and again begged for DNA. This time the match was positive. When a newfound cousin sent a photo of Charles, Rodney showed it to his mother without preface, and she gasped. “That looks just like your daddy!”

Charles Lynde came from a family of lawyers and judges. In high school, Rodney had dreamed of becoming a doctor, but none of his known relatives had ever entered a profession, so his dream remained only that. Now, all of a sudden, he had family who had walked tall. Paul Lynde was a distant cousin, but better yet, Deacon Lynde had sailed to Massachusetts Bay in 1634 on the same ship as Anne Hutchinson, one of Rodney’s heroes. No doubt they chatted on deck.

Did Elsworth know? He named his firstborn son Homer, after the man he was told had been his father. But he named his second son Charles.

Bertha lived next door to her son’s family. Had she casually suggested the name, knowing Elsworth would never dream that she was naming his real father? Or maybe she was not sure, and Elsworth and his wife just liked the name “Charles”?

The past is greedy; when it gives up its secrets, it snatches a few bits to keep.

“I just hope it was something Bertha wanted as much as Charles did, and it didn’t damage either of them,” Rodney says. “I wonder if he knew he was a father.” And I wonder if knowing all this would have made any difference to Rodney’s dad, the son named Charles. Secrets detonate after the players are gone, leaving the most intriguing questions unanswered.

Charles Joseph Lynde on his wedding day (Photo courtesy of Rodney Wilson)

Rodney’s metaphor is a jigsaw puzzle: “Life is collecting pieces, trying to understand ourselves, our families, our communities, our world. But we die with the puzzle unfinished.” Still, he had found a corner piece, one that tied the past and present together. “Lincoln talked about the mystic cords of memory,” he says softly. “There is something mystical about human history, about remembering the past. It’s the closest we will ever get to time travel. And DNA is mystical, too—it’s an instruction book that in nine months can create a human being. Knowing there was someone at the Massachusetts Bay Colony who had a little piece of my DNA—that helps me place myself a little bit more. History becomes less abstract.”

• • •

While I am learning Rodney’s story, I hear that Alexander Nemerov is coming to WashU to witness the donation of 513 secret letters his father, the famous poet Howard Nemerov, wrote to a woman named Joan Coale over a span of twenty years. They were lovers. No one ever knew.

An affair is a secret that maybe ought to be kept, at least until it loses its sting. Did I just write that? Me, who thinks every other secret should be revealed, because human nature is so fascinating and if we all talk freely, we can figure it out? But I would not want to know about an affair, could not handle the knowledge with any grace at all.

Alexander, too, admits to a little ambivalence about this whole thing. But when Joan’s son Howard confides his own father’s infidelity, the conversation relaxes. Learning this secret, Alexander decides, is bringing him “into the realm of the true, which is probably always joyous no matter how emotionally complicated it is.”

By the end of this informal, amazingly candid ceremony, one of the archivists is so moved, she confides a deep family secret her mother learned only late in life.

Later the same evening, I open last year’s Best American Essays and chance upon the story of a woman whose little sister was taken away at age one because she was, in the words of the time, “profoundly retarded.” Nobody ever talked about it. Her parents felt they were doing their older child a favor, making it possible for her to grow up unencumbered by stigma. But when asked what she remembers of her baby sister’s disappearance, she says, “It felt like losing an arm or a leg.”

II. Baffling shame

Just how many families lock secrets in their attic? On Facebook, I toss out a query, thinking one or two people might be willing to offer an anonymous example.

The replies fly in so fast, I cannot keep up. Juicy misadventures. Old stigma, yellowed and brittle. Shame that cut so deep, it lasted for decades.

One woman, call her Norah, writes that her mother, “adopted by loving childless couple,” was the biological child of her adoptive father and the sister of her adoptive mother. Deceived from the start, she grew up and “married my brother’s father, then my father’s brother, then my father, and then her fourth and last husband.”

I beg her to repeat all that, slowly. Her mother married and had a son. Then she divorced and married a second time, but the new husband treated her terribly. His brother saw this and rescued her. They married and had two daughters. Then, while in Germany with this third husband, she fell in love with a man who was younger than her son, and they left Germany to be together.

“None of this was talked about,” Norah explains. “My brother’s last name was changed. Mom pretended to be ten years younger than she was, even on her driver’s license and passport”—than added the decade back when it came time for Social Security. Norah reconnected with her mother, but the relationship stayed strained, and she says she “wasn’t permitted to call her ‘mom’ lest her friends find out.” She was introduced as “the daughter of a friend from Germany.”

Years later, she asked a priest, “What’s so bad about lying?”

“Our greatest desire is to be known,” the priest replied, “and no one can know you if you lie.”

• • •

The next woman, call her Mary, learned only recently that her grandmother got pregnant before she married, and her future sister-in-law took her to have an abortion. Did they even tell the baby’s father? Nobody knows. “My grandma had at least one nervous breakdown,” Mary says, “and later in her life, when she was in the nursing home, she told us she saw a baby’s face in the doorknob and asked if that could have been the baby she got rid of.” She was a devout Catholic and selfless, tireless worker her whole life, Mary adds. “I can’t help but wonder if she was trying to ask for forgiveness.”

Another woman, we will call Anna. (So many pseudonyms, despite the eager relief of telling the secret. Too many other lives have become enmeshed.) Anna’s grandfather sexually assaulted his two daughters. “If you mention this to your mom, it’ll kill her,” they were told, because their mother was in poor health. One night Anna’s mother was on the phone with her fiancé, and her father came into the room. “Act like you’re going into the other room, so he won’t suspect you’re leaving,” the fiancé said, but she was so scared, she ran outside and hid in a bush down the street until she saw her fiancé’s car. “My entire childhood, I never knew why my dad was so standoffish at family events,” Anna says, “and why I was never allowed to stay the night with my mom’s parents. I think she was in such a rush to get married—she turned eighteen on March 1 and married on March 6—because she wanted out of the house. Deep down, I think it affected her confidence, and it certainly affected her choices. I feel like she’s only recently started living her own life. I think she could have been an entirely different person.”

• • •

Next I hear from a woman who grew up thinking her mother was an orphan raised by a childless aunt and uncle. Only after her mother’s death did she learn that her grandfather had abandoned the family, her grandmother had lost hope and killed herself, and her mother had been made a ward of the court.

What does it mean, to learn that your mother’s mother took her own life? Can you see this as an expression of unbearable pain, or will it always feel like the ultimate rejection? A man writes of learning—casually, from a hospital doctor—that his grandfather killed himself. Was that why his father had so often been aloof, brooding, withdrawn?

The third generation feels the impact without understanding it. When they learn the secret, the news is huge, dramatic, devastating—yet over. By which I mean, hard to grieve. Shocking yet remote, cooled and distanced by time, useful only to explain the behavior that followed. Those with imagination and a ready sympathy will feel a pang, conjure the desperation, let it touch them. Others will shrug, bemused by the long concealment.

Years later, she asked a priest, “What’s so bad about lying?” “Our greatest desire is to be known,” the priest replied, “and no one can know you if you lie.”

Are there fewer secrets, now that we tell all? So much stigma has bled off. To new generations, the secrecy of the past is often baffling. A secret is a woman laced so tightly into her velvet gown that she cannot breathe or speak. We show up in jeans.

III. Keeping other people’s secrets

One man wants to know, his tone challenging, if I have any family secrets. Yes, but they are banal. My mom hated admitting that my father was twenty years older than she. My great-aunt Kitty was a war bride, and her husband lived but never came back to her. Aunt Mary fell in love with someone inappropriate but nothing happened.

My husband’s family has all the color, but who could keep it secret? A great-aunt who was the first female bookie, famous all the way to Vegas? Her sister, who ran a brothel and invited the drag queen entertainers to Thanksgiving supper? (Arrested for serving booze during Prohibition, she said slyly in court that she ran an upright establishment, which most of the men in the courtroom would know, having frequented it.)

Even to hear bland family stories, I had to pry them out of my mom, who cherished no affection for the past. At least she obliged. Robin Fivush has studied what children know about their family histories; she says that when families talk in “coherent and emotionally open ways” about their hardships and struggles, children cope better in times of crisis or stress. They have less anxiety, higher self-esteem, and more resilience.

What about those charged with keeping secrets, though? Tell me nothing; I find secrecy an almost impossible burden. But I admire those who can be trusted. Loyalty has forced them to lie by omission, again and again. I do not say that in censure. Lies can be told in love.

Paul [a pseudonym] came from one of those big, high-achieving families whose lives the whole neighborhood follows eagerly. No way were they going to admit that his sister suffered with mental illness, let alone that his big brother fell in love with his high school teacher. For the longest time, their parents did not even know. Paul, who worshipped his big brother, became his only confidante. Late at night, Paul would watch his brother push his old Pontiac with the door open, run to catch up, jump in, and start the engine safely out of earshot.

Shocking yet remote, cooled and distanced by time, useful only to explain the behavior that followed. Those with imagination and a ready sympathy will feel a pang, conjure the desperation, let it touch them. Others will shrug, bemused by the long concealment.

Being part of the secret made Paul feel grown-up, trusted. But his brother’s love affair shattered the black-and-white Catholic moral code Paul had memorized. “Do you say to yourself, wow, that’s really fucked up, she’s his teacher? Is this a gender-reversed Lolita? What is it? The lesson for me ultimately was look, there is a purity to this emotion that steamrolls over a lot of conventional rules.” He understood his brother’s need for secrecy, even beyond parental disapproval: “You are the guy who fucked your English teacher—that’s a pretty strong label, and not one that leaves much room for anything else.” Keeping the secret was tough, but exciting: “There’s a notoriety that accrues to you—secretly. I know something you don’t know, to the tenth degree! It’s the power to destroy, and on the flip side, the power of restraint.”

Paul’s brother stayed happily married to his English teacher for thirty years, until she died during the pandemic. I file this with another surprisingly happy marriage, this one beginning in bigamy:

“Uncle George married his high school sweetheart, then went off to World War II,” says Sarah [also a pseudonym]. Stationed in San Francisco, convinced he would die before he could get home again, he had what was meant to be a final fling with Elaine, a seventeen-year-old waitress who took his order at a diner. They fell headlong in love—and he married her. Then, when his beloved grandfather died, he went home for the funeral, never dreaming that his (second) wife would follow to be by his side. Elaine showed up at the funeral, and by the time the casket was borne out, George had been arrested.

Once the shock faded, his family rallied and allowed both wives to live in the family home, but that worked as well as you might imagine. Elaine returned to California, and George got a divorce and joined her there. They remained happily married for half a century. “They were the only older couple I ever saw still flirt with each other, even when he was in his eighties,” Sarah remarks. “But they never talked about any of this.”

IV. Misattributed parentage

Three years ago, researchers at Oxford’s Big Data Institute created the largest ever human family tree. Their eventual goal? To map all genetic relationships, giving all of humanity a single genealogy. For now, though, we search on our own, each hunting the particulars of our own peculiar family history—and uncovering secrets along the way. “Misattributed parentage,” this is called, and the fallout fills the advice columns.

So many secrets hinge on parentage. This will sound like heresy, but maybe it should not matter quite so much. People break through DNA’s predictive constraints all the time. They run away from home, change religion, defy expectations. Nonetheless, it is our parents who set the framework we must then shatter. And if they were not who they said they were….

Karen [a pseudonym] grew up thinking she was German and Sicilian. Then she found out that her grandmother had worked as a nanny for a Jewish family when she was sixteen, and the father had raped her. His wife, of course, did not believe her, so she was dismissed. But the father met her secretly so he could hold their baby. When Karen, intrigued to have Jewish ancestry, told her mother she knew the story, her mother burst into tears: “Your grandma made me live with a lie my whole life!”

Conception is a slippery thing.

“Well, I’m a secret,” Dusty Rhodes begins. Born in a Texas home for unwed mothers, she was adopted at birth. She grew up, became a journalist, and gravitated toward civil rights issues. Whenever she was in a comfortable space with Black people, someone would always ask, ‘Hey, are you mixed?” “Black people have always known that Black comes in all shades,” she says wryly. Whites never asked; “mixing” was so forbidden, it simply did not register.

Robin Fivush has studied what children know about their family histories; she says that when families talk in “coherent and emotionally open ways” about their hardships and struggles, children cope better in times of crisis or stress. They have less anxiety, higher self-esteem, and more resilience.

Dusty’s adoptive mother saw it, though. She lamented the broad, flat shape of her daughter’s nose, nixed playdates with Black classmates, and tried desperately to keep Dusty from choosing a Black roommate in college.

A few years later, Dusty found her birth mother, and they began corresponding. Her mom declined to meet—until Dusty accepted a job at the Anchorage Daily News and wrote that she was leaving for Alaska. “Then we met,” she says. “In a motel on the edge of town, like a drug deal.”

Eventually, her birth mother shared the name of Dusty’s birth father, an erstwhile artist turned car salesman living in Las Vegas. He, too, was White, so she figured all those people must have been wrong. Then she met his daughter, Monica.

“It was the first time I felt kin to somebody. Just her voice, and her timing, and her sense of humor. And she had a similar nose! She asked if I got teased in school, and I said yeah, they called me [N-] lips. She said, ‘You know we’re part Black.’”

Monica’s cousin had sent a family tree, showing both paternal grandparents as biracial. Apparently the lighter-skinned family members had left Texas for California and reinvented themselves as White. But Dusty’s great uncle, Warren G. Harding Crecy, was one of the most decorated Black officers of World War II. Dubbed the baddest man in the 761st”—the first Black tank battalion—he was awarded a Silver Star for heroism during the Battle of the Bulge, and a building at Fort Knox is named after him.

Dusty groans, thinking of all the relatives she could have known. “I always felt like a thing that hatched in a swamp. I didn’t feel connected to anyone; it was like I didn’t fit in with anybody. I think this is part of why.”

To this day, she is listed only as Friend on her birth mother’s Facebook page. Which breaks my heart. What we need, more than anything, is for our parents to be wildly in love with us, thrilled to have us no matter how, proud of us no matter what. To be a source of shame, by the accident of your birth, for the rest of your life? Little is less fair.

• • •

Carlyn Montes De Oca always knew who her clan was. In college, she even made a pilgrimage to the town of Montes De Oca, in Spain’s Basque hills.

Then she had her DNA tested. On a lark, because her mom once spoke of Jewish lineage, which Carlyn thought would be cool. But the report showed her to be only 3 percent Jewish, not the 40 percent her cousins were. And those cousins did not even show up as connections.

Instead, a woman’s name was listed as a potential half-sibling. Montes De Oca paid it no attention—until a man with that surname messaged her on Facebook to say she looked like his wife. Who had also had her DNA done, eager to find family.

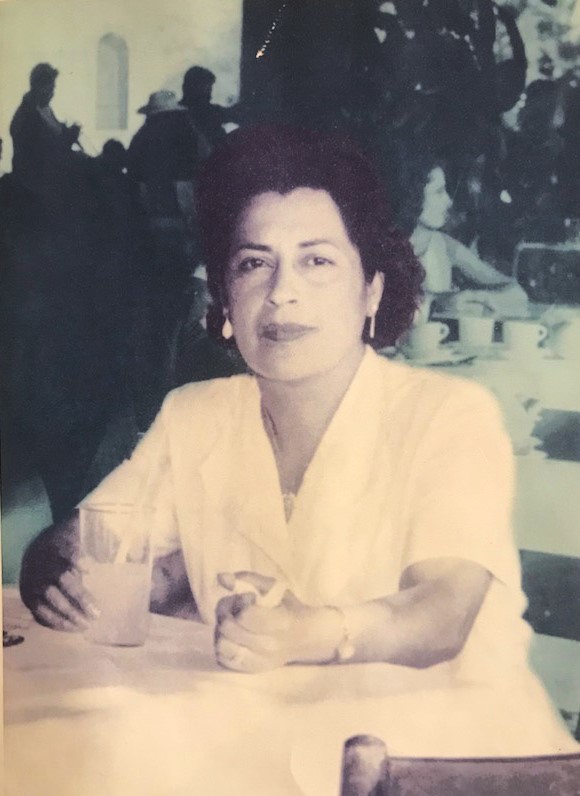

When Montes De Oca brought this up to her usually loud and laughing siblings, they fell silent. A week later, her sister came to see her and, crying, fumbled in her purse for an old Polaroid. “You were adopted at birth,” she blurted.

Keeping the secret was tough, but exciting: “There’s a notoriety that accrues to you—secretly. I know something you don’t know, to the tenth degree! It’s the power to destroy, and on the flip side, the power of restraint.”

Visiting a friend, Carlyn’s adoptive mother had heard a woman crying in the backyard. “Oh, that’s my cousin,” her friend said. “She’s pregnant and not married, and she already has two children, so she wants an abortion, but I’m not about to help her get one.”

Despite struggling to feed three children already, Montes De Oca’s adoptive parents said they would raise the child. “This is your new sister,” they told their children, “but you are never to tell her she was adopted. You are here to protect her.”

Montes De Oca was furious. Three siblings and sixty-three cousins and nobody had ever told her the truth? “I don’t even know who I am now!” she wailed. All that medical history she filled out at doctor’s offices? Fiction. “I had no idea how attached I was to my identity until it got taken away,” she says. Yes, yes, she knows her adoptive mother saved her life and she ought to be grateful. “But you don’t want to be lied to.”

Mary Montes De Oca, mother of Carlyn Montes De Oca (Photo courtesy of Carlyn Montes De Oca)

• • •

We say blood is thicker than water, but I am not convinced. As an adult, I met, for the first time, a few cousins from my father’s side. I fell in love with them, warmed by traits I was delighted to claim a connection to. Yet the sudden intimacy felt awkward, because it had not been built up by layers of shared hopes and crises, holidays and rituals. We were strangers who shared blood. How much was that worth? I am still not sure. Genes say a lot about who we are. The patterns of preferences, vocation, interests, and traits in twins separated at birth are uncanny. Yet our genetic predispositions are shaped and tweaked every day of our life, and the people who share those experiences know us far better than those who share only our DNA.

“What makes us the wise species—sapiens, remember, is the Latin for ‘wise’—is that our genes make brains that allow us to pick up things from one another that are not in our genes,” writes ethicist Kwame Anthony Appiah.

V. Lies that bind

There are too many secrets. Gail Pennington, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch TV critic for years, tells me that her grandfather lost his eye trying to rescue his nineteen-year-old sister-in-law, who was “caught in a love triangle” with an older, married man. She was shot to death, and he was wounded. At the murder trial, her mother was blamed for “raising a slutty daughter,” Gail says. “She lowered a cone of silence over the entire event.” None of the many people who knew what happened ever told. Gail only learned the truth after somebody wrote a rather bad true-crime novel about it.

“My birth mom sort of murdered a husband,” one Facebook reply begins. The writer, call her Jill, had always known she was adopted. Year by year, she pieced the truth together, and eventually found her biological brother, also born out of wedlock. Their mother later married—four times. Once to a gangster and safecracker, twice to police officers. Her second husband owned a bar in South City and allegedly came at her one day during an argument, so she grabbed a gun from a shelf behind the bar and shot him.

Years later, Jill and her brother, who is the spitting image of her, can commiserate. All the lies hit him harder than they did her, she remarks. Yet when her birth mother refused contact, it had to sting.

I say it is the secrecy that does the damage, but that is not always true. Even worse is learning the truth and being rejected by it.

At least there is a little joy in the truth learned by the short, dark woman whose family was tall and fair-skinned. Not until her mother was on her deathbed did she learn that she had been conceived in the jubilant celebration after World War II, when everybody was drunk and dancing in the streets.

Then there were the four Sicilian kids who, it turned out, were all fathered by the neighbor across the hall, hence their Native American DNA tests. And the smart, beautiful woman with a glamorous job—if you knew who I meant, you would have assumed she had a perfect family—who was brought up to call her stepfather “Daddy.” “I didn’t meet my actual birth father until I was in my forties,” she says. “And my stepfather had his own secret: he browbeat us five kids with stories of how inadequate we were, compared to him as a ‘tough Marine.’ At his death we learned that he had only lasted six months before being dismissed as ‘unfit.’”

I say it is the secrecy that does the damage, but that is not always true. Even worse is learning the truth and being rejected by it.

There is more to it, and there are more stories. But why do I feel this need to retell them all?

To speak them into public. To drain off the shame. Jung called secrets “psychic poison”: they isolate the keeper of the secret, require lies, breed distrust, and become the unwanted inheritance of a generation bewildered by the need to keep them.

Blood was once oath and destiny. Now that we are past that, and no longer feel bound by its script, it is easier to learn a dark secret. Now, blood only matters when we want it to.

VI.

Nina Meyerhof and her sister, Mona, take turns joking and weeping as they box up their dead mother’s books, perfumes, and cashmere sweaters. Then Mona slides out a box, and Nina breaks off mid-sentence. Not moving, not speaking, they stare at the box.

Pandora’s Box, they used to call it. The box of letters their mother kept hidden in her bedroom. The box she refused to open and warned them to never, ever touch.

Slowly, Mona lifts the lid. Inside is a stack of brittle, airmail-thin sheets. Nina picks up one of the letters and squints at the graceful swoops of faded ink. Doing this feels almost wrong, like a joke too dark to be funny. Their mother never wanted them to see these letters. Or did she just not want to be with them when it did? She could have burned the letters long ago, but here they are.

Nina and Mona grew up in silence, their mother wrapping them in its safe, warm blanket. She wanted her girls to have the joy she had lost; to live carefree. But Nina used to tiptoe and eavesdrop, catching snatches of their parents’ tense, urgent whispers: Deutschland and shoa and tot (dead), and that odd, sharp-angled word, Holocaust, that always made their mother cry.

Gerda had been a great beauty—a model, until someone realized she was not Aryan—and a freethinker, with her tuxedos and long cigarette holders. She married young, and she and Hans stayed out late in Berlin’s cafes, talking passionately about art and philosophy and literature. No one thought much of the little man named Hitler.

Until he declared himself Führer.

In the summer of 1938, Gerda and Hans booked passage to New York, worried about the way Germany was changing. They begged their parents—her widowed mother, Else; Hans’s mother, Kathe, and his stepfather, Edwin—to come with them. All three refused. They had flourished in Germany and refused to be uprooted.

On November 9, Kristallnacht, the Nazis destroy more than 1,400 synagogues and tear apart Jewish businesses, schools, and homes. Thirty thousand Jewish men are rounded up and taken to concentration camps. Else, Kathe, and Edwin realize they should have left. But more than 300,000 Germans, mostly Jewish refugees, have applied for U.S. visas, and only about 27,000 visas are available.

In September 1939, World War II officially began, and mail delivery grew erratic. In January, a letter from Kathe came through, telling Hans and Gerda not to worry about securing passage, because it will take a year for their quota numbers to come up. After another long gap in mail delivery, Else wrote of “the death of one’s spirit” from worry, fear, and isolation. “It is so lonely for me that sometimes I am afraid to say my thoughts aloud.”

Secrets can be exciting or sordid or absurd, but mainly, they are a burden. People place that burden, perhaps unfairly, on the rest of their family forever. But forever never lasts.

By now, Jews in Germany were stateless, their passports invalid. All U.S. embassies and consulates in Germany had closed. Germany refused to accept anything but German currency. Hans forged a desperate new plan, but his stepfather was scathing: “Now you’ll try to arrange something through Cuba? After you weren’t even able to pull together the much smaller sum for the USA?”

In March, Kathe and Edwin were deported to a ghetto.

That May, in New York, Meyerhof was born. Her grandmother Else looked longingly at babies in their carriages in order to imagine her. But Operation Reinhard, codename for the German plan to systematically “exterminate” all Jews, had begun.

That September, Else, too, was deported.

• • •

At first, Nina could only bear to skim the Pandora letters. But when an invitation came to visit Auschwitz—something she had never wanted to do—she accepted. She was beginning to realize how much of her life—the insistent risk-taking, travel, and exploration; the teaching of leadership and peace activism to kids all over the world—had been a reaction to her parents’ pain and buried guilt.

“We are,” writes Appiah, “entitled to a life informed by the fundamental facts about our existence. Even the painful ones? Perhaps especially those.”

The stories I am hearing are packed with life, death, sex, mystery, eccentricity. But it is the tone of voice that tells the real story: relief. Secrets can be exciting or sordid or absurd, but mainly, they are a burden. People place that burden, perhaps unfairly, on the rest of their family forever. But forever never lasts.

The past can be silenced for decades, even centuries, but it will continue to exert invisible pressure. And eventually the locks will rust, and the hasp will fall open, and the secrets will come tumbling out anyway.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.