On Saturday, September 11, Evander Holyfield, who turned 59 in October, was knocked out in the first round by the 44-year old former UFC champion, Vitor Belfort, in a commission sanctioned bout in Florida.

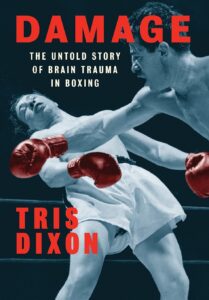

If the promoters or the people who lined their pockets working this event or, for that matter, the viewers who shelled out fifty dollars to watch the degrading spectacle, had read Tris Dixon’s Damage, maybe they would have passed on this so-called fight. Then again, I doubt it.

For all the hand-wringing about chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in the NFL, there has been scant media mention or public concern about brain trauma in boxing. And yet, as one of Dixon’s interviewees framed it, “Boxing is American football head injuries on steroids.” Maybe the silence voices the widespread belief that men and women who climb through the ropes, especially to make a living, do it of their own choice and know the dangers. If nothing else, Damage informs us that professionals in the stylized warfare of pugilism really do not grasp what they are getting into, either because they are uninformed or self-deceived.

Written by a quondam amateur boxer and celebrated ring scribe, Damage is a fluid combination of medical history, scientific facts, and personal narratives. Half of the gracefully written text is focused on the connection or, much more commonly, the lack thereof between the medical and boxing communities. As Dixon reveals, for over a century, doctors, who were not necessarily opponents of the sport, have been trying to tell us, “beating each other’s brains out” might be an apt image of what transpires in the prize ring.

For all the hand-wringing about chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in the NFL, there has been scant media mention or public concern about brain trauma in boxing. And yet, as one of Dixon’s interviewees framed it, “Boxing is American football head injuries on steroids.”

The opening rounds of Damage chronicle the initial attempts to take systematic note of what was then crudely referred to as the “punch drunk syndrome.” One of the first medical experts to champion the safety of pugilists was “Dr. Harrison Martland . . . born in 1883 during the reign of the first world champion John L. Sullivan.” In a 1928 article published in the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association, Martland defined “punch drunk” boxers as those “who were losing their faculties in the form of slurred speech, awkward movement, memory loss, and other degenerative behavioral changes” (3) such as suicide, violent outbursts, and even murder. Dr. Martland warned, “Half of all participants could be at risk ‘if they keep at the game long enough.” (5) How long is long enough, which is to say too long, is the parent question of this text.

Following Dr. Martland, J.A. Millspaugh investigated the effects of boxing-induced CTE and in the thirties managed to recast “punch drunk” into the medical terminology of “dementia pugilistica.” Dixon’s comprehensive account of the medical research includes a chapter on the Cleveland Clinic’s Professional Fighter’s Brain Health Study, the most recent and comprehensive attempt to cushion boxers from their trade. Based at the Lou Ruvo Center in Las Vegas and directed by Dr. Charles Bernick, this ongoing research probes fighters with an array of tools including MRI’s, cognitive tests, interviews, and speech analysis.

Far from pursuing purely academic goals, Bernick is searching for “The Holy Grail . . . a biological marker of when a fighter should retire before it is too late.” (135) Dixon reports, “More than eight hundred fighters have signed up for this study which started in 2011, and involves annual tests.” Even though Bernick and his crew do not reveal test results to boxing commissions, many fighters are naturally chary about taking part in a study the results of which might count out their career. The encouraging news is that because of this study, “The Nevada Athletic Commission now makes all of its athletes undergo a test to help track brain function over time.” (135)

As Dixon reveals, for over a century, doctors, who were not necessarily opponents of the sport, have been trying to tell us, “beating each other’s brains out” might be an apt image of what transpires in the prize ring.

For a select roster of Hall of Fame boxers whose brains were deforested by absorbing thousands of fistic bombs consider: Joe Louis, Ezzard Charles, Henry Armstrong, Sugar Ray Robinson, Randy Turpin, Muhammad Ali, Floyd Patterson, Wilfred Benitez, Aaron Pryor, Matthew Saad Muhammad. The register of punch-stricken wizards of violence could fill a telephone book.

As Dixon frequently reminds us, there are members of the boxing clan, George Foreman included, who insist the primary causes of debilitating breakdowns are post-retirement depression, drinking, and drugs. As a footnote, Ali was anything but a depressive and he never partook of either drugs or alcohol. Bernick acknowledges substance abuse complicates the CTE picture, but as Ali’s former doctor, Ferdie Pacheco, bluntly put it, “A moron could add up the picture of impending brain damage.” Pacheco was referring to late-career Ali but the ring doctor believed the same applied to anyone who imagined he or she can safely continue eating punches for decades.

Perhaps because of his boxing background and palpable respect for his boxing brethren, Dixon was able to gain the trust of both severely impaired fighters and their caretakers. They opened up to him. One surprise bubbled up in Dixon’s interview with Frankie Pryor, the wife of the late Aaron “The Hawk” Pryor. According to Frankie, there was no doubt that her husband’s methodical physical and mental destruction were the wages of a life in the ring. As the once dazzling Hawk began his long descent into dementia, Frankie found an informal support group in other boxing widows. But there was one woman missing, Frankie confessed. She, “wished that Lonnie Ali, Muhammad’s wife, had publicly acknowledged the reason behind the icon’s demise. . . . Instead, Ali’s family chose to say, ‘Oh, he has Parkinson’s. It has nothing to do with his boxing. . . . It has everything to do with boxing’.” That denial, Frankie claimed, “. . . pissed off a lot people in boxing.” (179)

The myriad accounts of boxing superheroes being transformed into toddlers is heart-wrenching. Dixon recounts the fifth act of two retired boxers and their devoted dad. The fight game dropped these former fistic prodigies off at a nursing home in Oregon.

Denny and Phil Moyer’s father bathed, washed and fed his boys. He did everything a parent should do. He helped them find the words they could not locate. He looked after them and made sure they wanted for nothing. The problem was that Denny and Phil were adults. . . . Denny was seventy and Phil was sixty-two. Their father, Harry, was ninety-five and he helped take care of them like this for over a decade. (165)

Once intensely popular but now marginalized, boxing has slipped off the sports pages. Still, make no mistake about it, icons like Joe Louis and Muhammad Ali inspired the lives and hopes of people more than any other professional athletes in American history. Joe Louis held the heavyweight title for twelve years. Jackie Robinson once proclaimed that without his friend Joe Louis there would have been no Jackie Robinson. Like Muhammad Ali, the “Brown Bomber” was a pillar of strength Black people could identify with and tap into. But even mighty Joe Louis could not defeat father time, nor could he understand when enough was enough. Years after his retirement “. . . his wife Martha began to note behavioral changes. Sometimes he would go days without changing his clothes. . . . He became reclusive. Paranoia started to set in and he feared the Mafia was out to kill him.” (31)

Even though Dr. Charles Bernick and his crew do not reveal test results to boxing commissions, many fighters are naturally chary about taking part in a study the results of which might count out their career.

Almost every one of the boxers and trainers Dixon engages concur that while there are often early signs of being poisoned by punches, it ordinarily takes about a decade for the real damage to make its horrendous landfall; however, when it does it invariably reduces the strongest men and women to rubble.

For those unfamiliar with the engine room of the fight game, it is important to recognize that for every bout, especially at the elite level, there are usually one hundred plus rounds of sparring. Dixon observes that according to CompuBox, counting only his filmed fights, the evasive Ali was tagged with a total of 8,877 punches in forty-seven of his sixty-one professional contests. And for each of those tussles, Ali prepared by sparring countless rounds with the likes of Larry Holmes, Jimmy Ellis, Michael Dokes, and other contenders.

The prizefighting industry is crowded with people blathering about enhancing the safety of boxing. At bottom, it is not the science, the technique they admire. Many of these same folks literally start blubbering when they witness demonstrations of courage and mutual destruction exhibited in the likes of the blood baths between Mickey Ward and Arturo Gatti.

In part because each state and country has its own boxing commission, making meaningful reforms is about as likely as a Golden Glover besting Canelo Alvarez. Dixon sighs, “There is an awful lot of hoping for the best in this sport, but at no point is getting hit in the head beneficial.” (205)

In the end, Dixon’s monitory work of love should serve as smelling salts to all of us involved in the world of the ring.

Still, here and there, the author serves up a few feasible suggestions. Dramatically cut the sparring down. Instead of 8 counts have 3 counts, because if you need 8 seconds to recover from a knockdown, you are surely concussed. Do not permit headshots in young boxers until the age of 14. Educate trainers and referees to halt lopsided contests. Improve the quality of ringside “physicians” by making sure they know something about boxing and boxers. In all candor, even attempting to make these minor adjustments calls Don Quixote to mind.

Damage could be used for ammunition to outlaw boxing or simply make the case for its moral condemnation. Nevertheless, Dixon’s intellectual thrusts and the cumulative effect of his painful-to-read narratives of destruction, are targeted at providing the boxing community with the education gridiron players and coaches have been receiving for years and which in turn has changed the game and culture of football.

In the end, Dixon’s monitory work of love should serve as smelling salts to all of us involved in the world of the ring. As a veteran boxing trainer, I recommend assigning Damage as mandatory reading for everyone professionally involved in the sport Joyce Carol Oates rightly observed “nobody plays.”