Since Darren Wilson shot Michael Brown in August 2014, people have been telling Bob Hansman, “Your tours predicted Ferguson.”

“I wasn’t the one who said that,” Hansman specifies. “But other people said that.” From his point of view, his tours, which take outsiders through St. Louis, do not do or say anything revolutionary. People have been predicting something like Ferguson—and the resulting protests and reconsideration of black rights—for years. The tours, he explains, just say, “Wake up, people.”

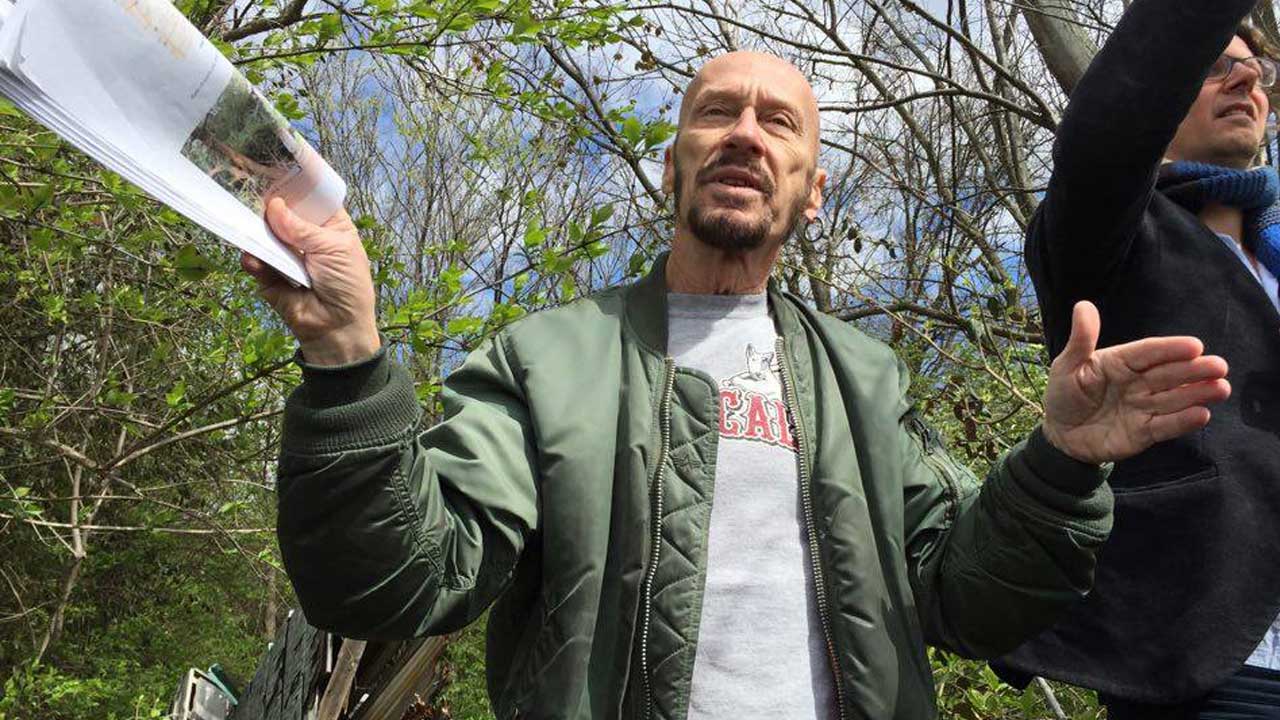

Hansman offers these St. Louis Community Tours through the Gephardt Institute, right now. He has three hours and one bus to tackle the monumental task of introducing people to all the things they never understood about how race has shaped St. Louis.

“People don’t really see any of the St. Louis communities as part of a larger picture,” he explains. “The impact communities have on each other, the historic reasons why things are the way they are—are patterns.”

The tour describes these patterns in five categories, dispensed in packets and supplemented by Hansman’s storytelling. The categories are “St. Louis and Missouri” (Hansman explains that the “and” should more appropriately be “versus”), “Government and Institutional Policy,” “Past & Present,” “Overlays,” and “Disappearing Black Communities.” They draw together photos, images, textual documents, and data from various times and places—all of which speak to the ways in which the structural interacts with the personal.

Hansman says that part of the problem is that while minority groups in St. Louis are very aware of patterns, white folks are not. And how can we talk productively about problems if some people do not even know they exist? The tours make a gesture at showing and explaining these patterns—perhaps in the hopes that something good will come out of it.

“It’s the black-white relationship that created what St. Louis is,” Hansman explains. But it is hard to capture that relationship in such a short period of time. His tours for Gephardt are condensed versions of multiple six, seven, even eight hour tours he leads during his community building course, in which students spend lots of time in various neighborhoods and learn how to productively interact with St. Louis’s communities.

To some extent, the larger patterns make the central narrative stand out more. Hansman explains, “You could go to all different neighborhoods tomorrow, but the basic story would stay consistent.”

But with limitations on time, Hansman has to choose his locations carefully. On April 1, he takes a fully-booked tour to a handful of places. The first is a bridge that runs over I-64, where the view shows the places the black communities in Mill Creek Valley used to be. “This is the graveyard of two great African-American neighborhoods in St. Louis,” he explains.

This tour is not based exactly around the individual buildings or places. “Where we are is like a backdrop for what I’m talking about,” Hansman says. “We’re gonna stand here and you’re gonna hear stories and I’m gonna paint this big picture for you while you’re standing here.” He asks people to stand in present, talk about the past, and look ahead to future—all at once.

Most of the people who live the realities of St. Louis communities do not end up working in academia. Because Hansman works in both worlds, he says it is easier for him to pass these stories between realms. “When I do these tours, it’s really like I’m taking people to my other life,” he says.

The stories he tells buoy this notion and are inspired by his own experience as an activist. Outside of his time at WUSTL, Hansman also teaches students in St. Louis city. “You can’t work with one foot in WashU and one foot in the projects downtown without suffering serious cognitive dissonance,” he explains.

Most academics do not live the realities of St. Louis communities; most of the people who live the realities of St. Louis communities do not end up working in academia. Because Hansman works in both worlds, he says it is easier for him to pass these stories between realms. “When I do these tours, it’s really like I’m taking people to my other life,” he says.

The Dickson Street curb peeks out from beneath decades of dirt.

The second stop is the site of the future National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency project, where North St. Louis developer Paul McKee sold the remnants of a slowly-torn-down neighborhood. Just a block away stands the shrubs and trees that grew in over the ruins of Pruitt Igoe. Beneath the dirt, you can see the outline of Dickson Street, which ran between the black-designated buildings and the white-designated buildings.

Next comes Kinloch, which Hansman describes as “another black historic city: gone.” It was once a horse racing ring, then an airfield, and then became known as the first black city in the area, a town of rolling green hills. Now, bulldozer tracks churn through the mud, building the beginnings of a Schnucks distribution center. He shows us the Kinloch History Museum—a now-defunct building—and an incredibly old church people had hoped to preserve. The construction took away its supporting trees, and the wind knocked it over.

We stop last in Ferguson, where Michael Brown’s memorial plate sits in a sidewalk. Here, Hansman says nothing. But on the bus, he describes Brown’s death as “a moment in a long trajectory.” And he agrees with what many activists have said since that August: Ferguson was not unique. “There’s a lot of places more Ferguson than ‘Ferguson’,” he says.

On the tour, Hansman emphasizes that Ferguson highlights the need for white people to engage productively and responsibly. He recalls being hesitant to take students there, and being displeased with the ways people use Ferguson to credit themselves, saying, “Ferguson was becoming the latest excuse to do nothing everywhere else.”

He points to boards painted with flowers and doves as an example of bad community engagement. “Don’t go up there now and silence other people’s voices,” he remembers thinking. “Even if they’re vandals! Those are serious messages. Don’t try to whitewash it with something you think is nice, like a bandaid that dismisses the seriousness of what’s happening.”

And students were not the only culprits. “All the faculty want Ferguson on their resume now,” he says. “Most of them had to look it up on the map the first time they went. And they didn’t go until after Mike Brown was shot. They had no reason to go up there before.”

Hansman prefers the response of some students in his class who talked to business owners and found that they were worried about going out of business when their owners required them to board up against riots. The students painted attractive “we’re open” signs for the businesses.

Hansman explains that the difference is that with one, the boardups are still there but business are gone; with other, boardups are gone but businesses are there. The latter, he points to as more beneficial to the community.

But Hansman stresses that evasion is just as useless as bad engagement. Instead, he encourages people—especially white outsiders—to listen and respond, and take responsibility for their role in perpetuating racism and structural inequality. “Whether they like it or not, they and their families are part of American history,” he says. “Whether they like it or not, they are part of the problem, and they can be part of the solution.”