1. The taking of Pelham. . . 1, 2, 3

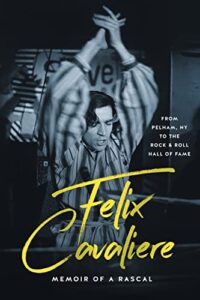

Felix Cavaliere (b. 1942), the founder of the famed 1960s rock group the Rascals (aka the Young Rascals), often practiced with his bandmates in the basement of his parents’ home in Pelham Manor, New York, in the early days when the band was unknown. “Discriminated against for being short, Italian, having a different name, being the guy with the long hair,” (14) as Cavaliere put it, made him an outsider. And rock and roll was the art form of the young outsider, Blacks, Jews, Italians, in the main, with gays and some poor White southerners thrown in for good measure.

Cavaliere had dropped out of Syracuse University, much to his father’s chagrin. A dentist, he wanted Felix to become a doctor. Felix’s mother was a pharmacist, an unusual occupation for an Italian-Catholic woman in the 1950s. She had Felix study classical piano. His father, whom young Felix did not know well, was nonplussed by his son’s desire to be a rock and roll musician. Had he become a classical pianist or a physician, that would have brought some degree of prestige, honor to this Italian American family. What prestige or honor was there playing in clubs and dives a raucous, sexually suggestive music that only teenagers liked and that Blacks originated?

His middle-class parents had sacrificed to move Cavaliere and his sister to Pelham Manor (15) so that they could get a better education (13) and so they would be among a better sort of people. His father was rejected for membership in the Pelham Country Club which at the time did not allow “Italians, Jews, Hispanics, and Blacks.” (15) Young Felix never forgot that slight. (15) Many Italian Americans hungered for bourgeois acceptance too.

His mother died on Felix’s thirteenth birthday. It disturbed him deeply for years that God would take his mother, a devout Catholic, at the age of forty-five. What kind of a God was that? What had his mother done to deserve such a fate? This angry and perplexed sorrow spurred his spiritual quest that would eventually figure in his music. But Felix did not stay with classical music to honor the memory of his mother. He wound up playing rock and roll, the music of rebellion, the music of the outsider. It is not hard to understand why it was attractive to him. Mocked as an Italian, disappointed by his Catholicism, physically unprepossessing, rock and roll offered the charisma of revolution. And revolution is always about how the odd get even. Cavaliere was sufficiently driven but, outsider that he was, he wanted prestige and acceptance on his terms, and, paradoxically, he wanted retribution too. Rock and roll gave him this in one contrary package.

His father was rejected for membership in the Pelham Country Club which at the time did not allow “Italians, Jews, Hispanics, and Blacks.” Young Felix never forgot that slight.

The music that poured out of the Cavaliere basement rocked the neighborhood. Their home “was directly across Pelham High School, and we’d have the basement windows wide open; the sound pouring out on the street. It wasn’t long before the kids began standing out on the sidewalk listening to the earliest days of what would become the Rascals. Pretty soon, it was a whole neighborhood scene, with teenagers out in front of Dr. Cavaliere’s house dancing and singing along to our music.”(43) In effect, rock and roll took Pelham High.

The Rascals, at that point, were bottom feeders in the music business, playing clubs and lounges, including an important gig in the Hamptons that got them discovered. Cavaliere had been a sideman with Joey Dee and the Starliters, learning his trade. The Rascals were, to use the jazz musician’s term, “woodshedding” in the basement between their gigs. Everyone in the neighborhood knew they were a band on the make. “Eventually, neighborhood people helped with our stage outfits, though not the schoolboy knickers that we wore during our earliest days of fame and fortune. Everybody pitched in because everybody felt like they had a stake in our success. We were like them. We were from the same place, and they wanted us to succeed.” (43) The Rascals were a community project.

Some Blacks, like soul singer Otis Redding, thought, at first, that the Rascals were Black. He was surprised to find out they were not.

One of the songs the Rascals rehearsed in the basement was originally a 1965 Black rave-up called “Good Lovin’.” (Televised performance here) Cavaliere had stumbled upon the single, done by an R&B group called the Olympics, “ransacking the bins [in a record store] in search of the sounds that stood out for me. Often it was the R&B tracks of black artists that lit me most intensely.” (10) The Rascals’ cover of the song in 1966 would become their first huge hit. (Ed Sullivan performance here with Cavaliere singing the lead.) Covering Black tunes was a common practice among White performers doing rock and roll in those days. The Rascals’ version was played on Black radio stations. Some Blacks, like soul singer Otis Redding, thought, at first, that the Rascals were Black. He was surprised to find out they were not. (63) There was something hip, young, and exciting about Cavaliere counting off “1, 2, 3” before the song begins. (Soul singer Wilson Pickett would count off “1, 2, 3” to start his 1966 cover of “Land of a Thousand Dances” which was recorded in May 1966. The Rascals’ “Good Lovin’” was recorded in March 1966. Who copied whom? Cavaliere knew Pickett; they both recorded for the same label.)

When I first heard that count, and then the intensity of “Good Lovin’” on the radio as a kid, it was unforgettable. Every Black kid I knew liked the Rascals. Yes, the Rascals were about the taking of Pelham. . . 1, 2, 3, the sound of young America.

2. Success, failure, and the solace of seeking

The Olympics were a Black singing group. The Rascals were a band. Therein lies a huge difference. Black groups like the Olympics were becoming anachronisms by the 1970s. The Rascals, like the Beatles and other such groups, were the way of the future in rock and roll. The Rascals were composed of four players: Cavaliere on organ, Gene Cornish on guitar, Dino Danelli on drums, and frontman Eddie Brigati, who shared lead vocals with Cavaliere and who was eye candy for teenage girls. It was no longer the case in popular music that one could be song stylist or song interpreter. One had to be able to play an instrument and sing.

If the Rascals were influenced by the Black jazz organ trio, they were also influenced by Black R&B singing. They were part of a movement in rock and roll in the 1960s called “Blue-eyed soul,” White performers who sounded Black or at least sounded “soulful.”

In essence, the Rascals were an organ trio not unlike the kind of Black organ trios that became popular in 1960s Black jazz led by organists like Jack MacDuff, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Jimmy McGriff, and the legendary Jimmy Smith. But this set-up, with a group like the Rascals, had now become a power trio in rock. Dave “Baby” Cortez showed that an organ could be a lead instrument in rock and roll with his 1959 R&B hit, “The Happy Organ.” The Hammond B-3 had found its place in Black popular music by the time the Rascals appeared. And it would become a major voice in 1960s Black and White rock with R&B groups like the Memphis-bred Booker T. and the MGs and rock bands like the Spencer Davis Group of Britain featuring organist and lead singer Steve Winwood.

If the Rascals were influenced by the Black jazz organ trio, they were also influenced by Black R&B singing. They were part of a movement in rock and roll in the 1960s called “Blue-eyed soul,” White performers who sounded Black or at least sounded “soulful.” Other White performers of the time who were popular with Black audiences were Welsh singer Tom Jones, the singing duo the Righteous Brothers (the name itself says it all), and Roy Head. It was Philadelphia disc jockey Georgie Woods (“the man with the goods”), whom I listened to religiously growing up, who came up with the term, “blue-eyed soul brothers.” Some might say that this amounted to a new type of minstrelsy, a sort of theft. Others might say that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Whatever it was, the Rascals were one of the trendsetters in this genre. The group was originally signed by Atlantic Records in 1965, the first White act to record for the label known for such artists as Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Ben E. King, the Modern Jazz Quartet, and the Drifters. (The White acts Atlantic had recorded for the subsidiary Atco.) Being on the label gave the Rascals the patina of Blackness.

“Good Lovin’” was the only big hit by the Rascals that Cavaliere and Brigati did not write. Their other major tunes—“Groovin’,” “A Beautiful Morning,” “People Got to Be Free,” and “How Can I Be Sure?”—were Cavaliere/Brigati collaborations. So, the Rascals fulfilled the other requirement of the new wave in rock— they wrote their own tunes. Cavaliere and Brigati were successful enough in this venture to have been inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2009, rather surprisingly considering their relatively small body of work, although there is no question about the popularity and staying power of their biggest hits.

Three of the four members of the group were Italian. The presence of Italians in popular American vocals was huge: Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Jerry Vale, Louie Prima, Vic Damone, Al Martino, Dean Martin, Perry Como, Bobby Darin, even the operatic Mario Lanza as well as 1960s teen idols like Frankie Avalon, Bobby Rydell, and Fabian Forte. In this respect, Cavaliere and Brigati came from a tradition of male Italian pop singers, regardless of whether they were directly influenced by them. While Cavaliere might have been entranced by Black R&B singers, his vocals have echoes of some of these Italian singers as well, the masculine bravura, the high drama mixed with a kind of street realism of the Italian kid on the block singing urban arias. Despite the fact that the Rascals were highly influenced by Black music, the fact that they were Italian gave them an aura of authenticity, or a kind of authority to perform the music they did.

It should be remembered as well that some Italian singers and groups were highly regarded by Blacks. Sinatra and Dean Martin come to mind immediately. But I remember Frankie Valli’s falsetto being greatly admired by many Blacks I knew growing up. A song like “There’s a Moon Out Tonight,” recorded by an Italian American doo-wop group called the Capris in 1958 but a huge hit in 1961, was played on Black radio stations. Lead singer Nick Santo’s falsetto impressed a lot of Black listeners.

His “Good Lovin’” audience did not want this sort of gauzy, sunrise and happiness stuff but jazz heads did not want it either, too outré for one group that wants hard-partying music, too bland for the other that wants more intellectually challenging music.

Cavaliere’s book tells the standard story of success and breakdown. The band members, as the saying goes, cannot stand prosperity and raging egos tear the group apart by 1972. Eddie Brigati was, according to Cavaliere, especially difficult. There is the usual stuff about drugs, sex, and the grind of being on the road. Cavaliere relates this at times in a disarmingly humorous way. He writes about his own life: two children in his early twenties with a woman he never married; a plethora of girlfriends; a failed marriage with three children; and a final marriage that seems to have worked. He was on the road a lot, so he did not see his children very much when they were growing up, as his own father worked hard as a dentist and did not spend a lot of time with young Felix. The trials and tribulations of the professional rock musician are mostly what is here. That is interesting but hardly novel.

The group signed with Columbia Records in the late 1960s, four albums for $2 million. (197) It was at this time that Cavaliere had become enamored of an Indian yogi named Swami Satchidananda, who became his spiritual teacher. (He devotes an entire chapter to Satchidananda and his influence, maintaining a relationship with the yogi for many years.) The other band members found Satchidananda a curiosity but nothing more. Cavaliere writes, “… the other Rascals were never really into the whole scene [with Satchidananda] and… they sometimes thought I’d lost my mind.” (181)

Looking east for spiritual guidance, ancient wisdom, had always been a thing among certain set of western intellectuals and artists dating back to the American Transcendentalists of the mid-nineteenth century. The Beatles, the group the Rascals most admired, had hooked up with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in 1968, although they renounced their association with him when it was discovered that the Maharishi was something of a rake. Holy men are supposed to be above being cock hounds. Books like Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha (1922) and Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi (1946) were popular with the young, counter-culture types at the time. Cavaliere had read Yogananda’s book and was still looking for answers about the God who take his mother away at a young age. Cavaliere credits Satchidananda with cleaning up his life: “I dressed all in white. I was vegetarian. I didn’t smoke. I didn’t drink. To be honest, the only thing I really had trouble eliminating was sex…. But I really tried to live by his tenets. I really tried. It was kind of like being a monk.” (178)

Some might say that this amounted to a new type of minstrelsy, a sort of theft. Others might say that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Whatever it was, the Rascals were one of the trendsetters in this genre.

What is striking about this is that the Rascals’ first album for Columbia was a two-record set entitled Peaceful World (1971) with a Gauguin painting on the cover. Both Brigati and Cornish had left the group. They were replaced by guitarist Buzz Feiten and singer Annie Sutton. In a way, the group had lost its collective identity and had become simply Cavaliere’s band. A host of guest musicians were featured, mostly jazz players like reedman Joe Farrell, bassist Ron Carter, flutist Hubert Laws, saxophonist Pepper Adams, and pianist/harpist Alice Coltrane, who herself was a devotee of Satchidananda and would establish her own ashram in California in 1983. The lyrics, the message here, is highly influenced by the presence of Satchidananda as well as the kind of spiritual jazz that was floating around at the time. One might say that Peaceful World was “blue-eyed soul music” of a different sort. His “Good Lovin’” audience did not want this sort of gauzy, sunrise and happiness stuff but jazz heads did not want it either, too outré for one group that wants hard-partying music, too bland for the other that wants more intellectually challenging music.

Both guitarists Carlos Santana and John McLaughlin had become followers of holy man, Sri Chinmoy. Pianist Horace Silver put out a trilogy of albums called collectively The United States of Mind (1970-1972), with songs about healthy life and seeking the spiritual life. There was Pharoah Sanders’s Karma, melodic pop with avant-garde moments, a kind of by-product of John Coltrane’s 1964 album, A Love Supreme, and his 1965 record, Kulu Sé Mama. Cavaliere wanted to add not just a strong jazz element to the Rascals but a jazz element that was coming from this particular sensibility. The music sounded a bit similar in aesthetic to albums like Santana’s Welcome (1973) and Caravanserai (1972), made at the same time as Peaceful World and The Island of Real (1972), albums that Santana wrote and recorded while deeply under the influence of his guru. The album was largely a critical and commercial failure. Cavaliere, aside from mentioning that Peaceful World is the Rascals’ most popular album in Japan, does not talk about this record, how it came about, why he did it, what Columbia thought about it, what it was like to work with musicians like Coltrane and Farrell. It is a startling omission. In fact, Cavaliere offers nothing about his years with Columbia and why it ended so badly there after he made Peaceful World and The Island of Real. Is this omission a repudiation of this stage of his career? Is he ashamed or embarrassed by Peaceful World and The Island of Real? Surely, that music is dated, but artists can learn something about self-acceptance by talking about their failures. It is sometimes more amazing what authors will refuse to talk about in a memoir than what they willingly confess.