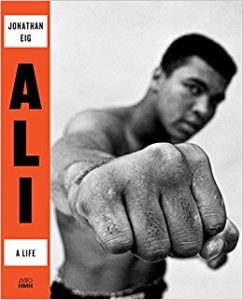

Like the Cinderella Man books published in 2005 about boxer James Braddock, from research in conjunction with the movie produced by Ron Howard, so has Jonathan Eig written Ali: A Life, released October 3, 2017, while working with Ken Burns to develop a documentary on the life of the world champion boxer, turned world-famous celebrity, turned legend.

Eig, a former staff writer for The Wall Street Journal, has compiled the most interesting and informative details from the best of the Muhammad Ali biographers, boxing historians, and Ali’s friends and family to give readers a comprehensive look (the review copy is a hefty 640 pages) at a complex life both blessed and cursed by the sports world’s toughest profession. Eig’s point of view is sociological (and highly cinematic in development), illustrating how Ali’s personality was shaped by the people and events of the turbulent middle decades of the 20th century.

Eig begins his discussion of boxing and the appearance of black boxers in America in a predominantly white sport with a quote from New York journalist Charles Dana in 1895: “The black man is rapidly forging to the front ranks in athletics, especially in the field of fisticuffs. We are in the midst of a black rise against white supremacy.” (42) Eig uses this quote to explain in the next sentence how the black boxer Jack Johnson “challenged the natural order.” However, Charles Dana was unaware of Jack Johnson in 1895, and the full quote identifies, “There were two negroes in the ring today who can thrash any white man breathing in their respective classes … George Dixon and Joe Walcott.”[1] Instead of using Jack Johnson’s belligerence to attack the “white order” (which Johnson did, but much later), it might have been more insightful for the historical context to explain how boxing, in all of its illegalities and bane to traditional social values, helped, as early as the 19th century, to integrate sport, promoting and enriching members of ethnic minorities more than any other sport. The point being made is that American boxing has had a long and very grand, albeit complicated, history of great black boxers that enabled the talented Muhammad Ali to rise to celebrity status. That place in history might have been the book’s contextual starting point considering that Ali mentions this fact: “I started boxing because I thought it was the fastest way for a black person to make it in this country.” (54) Fast forward to the 1960s: young Americans of Ali’s age (including this reviewer) were eager to champion a new and young public face, someone who had the prestige to challenge authority, the status quo, and the inequities of race. And while his braggadocio offended an older generation, Ali epitomized what was becoming the “Me Generation,” a point Eig could have highlighted.

From a very young age, Cassius Clay craved attention. He was a failing student who had to garner respect through acts of physicality and thinking outside the box at which he was an expert. When other kids would climb aboard the school bus, Clay would slink back to the end of the line and then run alongside the bus for the duration of the trip.

One of the joys of reading this book is that Eig adds interesting new biographical details that reshape the Ali narrative. It is common knowledge that young Cassius Clay, Jr. found his way into a boxing gym to tell a police officer/after-hours trainer that his bicycle was stolen. However, Eig tells us that the loss was not as stinging to Ali’s psyche as readers of the popular story may have concluded. Cash, Sr. and Odessa, Ali’s middle-class parents in Louisville, Kentucky, upgraded the $60 Schwinn to a more expensive motorbike to be shared between their two sons Cassius and Rudy, although the greater portion of the rides went to Cassius who enjoyed speeding around the city showing off his newest prized possession.

From a very young age, Cassius Clay craved attention. He was a failing student who had to garner respect through acts of physicality and thinking outside the box at which he was an expert. When other kids would climb aboard the school bus, Clay would slink back to the end of the line and then run alongside the bus for the duration of the trip. Occasionally, he would begin his run and then decide to ride a portion of the way hanging by his fingernails to an outside window sill. He came to realize that his antics were entertaining, allowing him to stand out from the crowd. Even his high school principal was convinced that Clay should be allowed to graduate amidst his failing marks because he was someone destined to become a special athlete.

What boxing gave the teenager, beyond the attention he craved, was an identity—as a “boxer.” He was not born a natural boxer. In fact, his style was terrible. But he could be found alone for hours at a time punching the heavy bag to improve his strength. What made him special was his hard work and determination to become a world champion, a fact sometimes overlooked because of his arrogant joviality. His first trainer, Joe Martin, reflected, “It was almost impossible to discourage him. He was easily the hardest working kid I ever taught.” (39)

As an amateur Ali won the National AAU light-heavyweight championship in April 1960. In May he went to the Olympic trials in San Francisco. To overcome his fear of flying, Eig tells us that Ali bought and wore a parachute while on the airplane. After he won an Olympic slot, he hocked the gold watch he was given so that he could buy a train ticket home. (His coach had already paid for a round-trip plane ticket and refused to buy the train ticket.)

The stage was set for the Rome Olympics. At age 18, he easily won all four fights to take home the gold medal. When Clay stood on the podium to accept the honor, it was one of the few moments the fighter was silent. Afterwards, he responded, “It’s gonna be great to be great.” (88) One of his classmates remarked, “Before [the Olympics] he was always kind of shy.” (92) Eig also rewrites the story about Ali throwing his medal in the river, stating that the precious award was in fact misplaced or stolen.

Clay turned pro and bought himself a Cadillac, a showy status symbol of the 1960s.

Those of us in Ali’s generation remember professional boxing in the 1950s somewhat like Norman Rockwell’s drawings, where athletes were expected to be a bit more humble than what the cocky new star brought to the ring stage. Like Clay, Floyd Patterson won a gold medal at the Helsinki Olympics in 1952 before turning pro. After Rocky Marciano retired in 1956, Patterson beat Archie Moore for the heavyweight championship. While Patterson represented everything old-school in boxing style and social decorum, the times were “a changing” as the Bob Dylan song from 1964 announced. Patterson lost and regained the championship to Sweden’s mediocre Ingemar Johansson, only to lose it for good in 1962 to ex-convict Sonny Liston.

In came Cassius Clay to beat Liston in 1964, in an upset as surprising as Patterson-Liston 1962, or even farther back, Baer-Braddock 1935. The similarities between Ali and boxer Max Baer of the 1930s are remarkable. Both were handsome young champions, childishly egotistical and international press magnets with their infectious charisma. Both owned three expensive cars before becoming champions—Ali’s were Cadillacs. Both were subjects for a new generation of literary writers: for Baer it was Hemingway; for Ali it was a group called the New Journalists. And both boxers sustained their popular appeal when their boxing accomplishments were over. Ali, however, embraced more than boxing.

Eig explains how the young Clay had been introduced to the message of Elijah Muhammad and the startling new revelation to him that the white race was an offshoot of black descendants from Africa. The Chicago prophet’s exhortations for blacks to break from white systems and rituals empowered Clay, causing him to abandon his family’s Baptist roots to join The Nation of Islam (NOI) headed by Elijah Muhammad. The leader equally embraced the new champion and endowed Cassius Clay with a name almost as sacred as his own. Muhammad meant “worthy of praise,” and Ali meant “lofty.” Young Cassius had always been proud of his birth name. He liked the distinguished sound of Cassius Marcellus Clay as it flowed from his lips. The surname was from the slave-owning Southern Senator, Henry Clay, who advocated for emancipation and denounced as evil the institution of slavery. But immediately after winning the heavyweight title, Clay announced that he should be called by his new Muslim name, “Muhammed Ali.”

White Americans had no idea what to make of this pretty champion, with an unorthodox style, sassy mouth, and a new affiliation to a group of black activists that advocated the separation of the races. When asked how much of his braggadocio was real and how much was just hype, Ali answered, “About seventy-five percent.” (121) So, he was honest. And backed by 75 percent talent, the 25 percent hype would make him a super-star, literally being photographed knocking over domino-style the four Beatles during their initial tour of America. The standard bearer for boxing, Jack Dempsey (who was as equally impressed with Max Baer thirty years earlier) said, “I don’t care if this kid can’t fight a lick. I’m for him. Things are live again.” (119)

Actually, Ali proved so strong and fast with his fists that at the Liston re-match the knockout punch was entirely missed by ringsiders. Yet Ali could not, or would not, slip a punch; he preferred to pull his head back awkwardly to avoid being hit. What Ali could not avoid was a collision with the military and the Vietnam War.

In 1964, Ali requested an exemption from service into the U.S. Army for religious and personal reasons. In a life-long list of contradictions, Ali had previously been found intellectually incapable of being drafted into the military because of the army’s intelligence test. But when the defense department needed additional recruits as the Vietnam War escalated, standards were lowered. When that failed to bring in the necessary numbers, draft deferments turned into lottery obligations. (The lottery was horrifying as this reviewer remembers sitting in front a television screen one night in the final year of college and waiting for her friends’ numbers to be called. It felt like death sentences being announced.) Ali refused induction. He was convicted and sentenced to five years imprisonment. As American deaths in Vietnam increased, Ali’s bold act energized anti-war protests. His legal appeals finally reached the Supreme Court, and in another strange twist of fate, the Supreme Court on the basis of a technicality over how the federal prosecution filed its charges, ruled in Ali’s favor, although the ruling was not based on the merits of Ali’s legal claim. (See HBO’s movie Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight, 2013, based on the book by Howard Bingham.)[2]

Ali was denied a license to fight by boxing’s sanctioning bodies and by state athletic commission from the time of his conviction until 1970 when Georgia granted him a license to fight Jerry Quarry. In total, Ali did not fight for more than three years. In 1974 he regained the title taken by the boxing’s power brokers by beating George Foreman in Zaire, in a world-famous event promoted by Don King, popularly dubbed “The Rumble in the Jungle.” The next year he beat Joe Frazier for the second straight time in the “Thrilla in Manilla.” (He had previously beaten Frazier in 1974 in New York when neither man was champion after he had lost to Frazier in 1971 in what was called The Fight of the Century.)

Eig does not give Ali a pass. He says that when Ali might have stepped in to help his former friend Malcolm X, the charismatic Muslim minister who built up the NOI in the 1950s and early 1960s, whose head became a target for the Nation of Islam when he started his own movement, Ali chose to inflame and support anti-Malcolm sentiment. Only later did he regret turning his back on his friend. These contradictions and complexities are wonderfully detailed in this book.

Toward the end of his career, when he was not as fast as he once was, he needed a new boxing strategy. He let opponents exhaust their energy by pummeling him against the ropes (to the horror of his trainer) in what came to be called the “rope-a-dope” strategy. Ali would pull out, and end the fight with his powerful show of force. The strategy proved a winning device in the ring, but one that brought long-term and heart-rending consequences to his boxing career. In fact, it was ring doctor Ferdie Pacheco that finally had to walk away from Ali’s corner after advising him that the blows were taking a toll on his brain and that it was time to hang up the gloves.

But Ali needed the money. Like many boxers, Ali was generous to friends, relatives, hangers-on, (and for Ali, the NOI), and anyone who offered a sympathetic story. And also like many boxers toward the end of their natural careers, Ali kept on fighting. The most valuable new research tools Eig adds to this study are the FBI files and CompuBox statistics. Eig shows how in Ali’s early career, he was able to avoid punishing blows. But toward the end of his career, his reflexes had slowed and he was absorbing more and more debilitating blows to the head as the punch-count numbers revealed. Did he fight too long? Most champion boxers find it difficult to give up the money and adulation, their greatest curse. And Ali needed the money to maintain a lifestyle with friends (he hated to be alone), nice homes (that were never empty), fancy cars (that were usually Cadillacs), a history of wives (there were four), and girlfriends (he had an insatiable sexual appetite for women).

Ali was a man of contradictions. Even though adultery is considered a sin in his religion, he had numerous affairs while married. And while Islamic law warned against taking a human life (which justified his military exemption as a pacifist)[3], the religion also barred sports, especially violent ones. While the NOI had turned a blind eye to Ali’s profession early on, Elijah Muhammad eventually banned Ali from the religion for a year for expressing a desire to return to boxing during his three-and-one-half-year exile from the sport. Eig does not give Ali a pass. He says that when Ali might have stepped in to help his former friend Malcolm X, the charismatic Muslim minister who built up the NOI in the 1950s and early 1960s, whose head became a target for the NOI when he started his own movement, Ali chose to inflame and support anti-Malcolm sentiment. Only later did he regret turning his back on his friend. These contradictions and complexities are wonderfully detailed in this book.

Eig stumbles a bit in overpraising the celebrity’s income. He states that Ali earned $1.2 million from 1964 through 1966 and that he was “almost certainly the best-paid athlete in American history up to that point, and by a wide margin.” (244) Prior to Ali, however, there were many well-paid boxers. Dempsey and Tunney both made over a million in the late 1920s. Gene Tunney made $1,000,000 in one fight in 1926.

Eig’s masterful storytelling captures the dialectic between the man with a dream of becoming the Greatest and the American social-political institutions at work to oppress the dream.

The task of writing a book that encompasses Ali’s entire life is not easy, especially considering the fact that potential readers already have some knowledge of the subject. Everyone has read something about Muhammed Ali, in a magazine article, newspaper feature, book, or has seen a documentary or Hollywood film about him. The complicated task for Eig is to re-tell the story in such a way that readers with varying degrees of knowledge about the man and the period, or those with a favorite Ali book, do not lose interest. Eig’s book succeeds, offering something new for everyone.

Eig’s masterful storytelling captures the dialectic between the man with a dream of becoming the Greatest and the American social-political institutions at work to oppress the dream. Thus, Eig cleverly explores the ironies of how Ali happened to be one of the luckiest and talented men of his generation caught in some of the most unfortunate situations and relationships.

Ali out-battled Goliath on every front. Was he afraid? Sure, he admitted later in life. He thought he would spend years in jail. He thought he might be assassinated, just as his friend Malcolm X had been assassinated or Martin Luther King or the Kennedys. Considering all the assassinations of the era, it was amazing that Ali escaped such an end. But his optimism was elegantly simple: God had a plan for him. (227)

In 1996, Ali was selected to light the Olympic fire at the opening ceremony of the games in Atlanta. Ali was as big as everyone remembered him, only silenced, in the last sad yet inevitable twist of fate of boxing induced Parkinson’s Disease.

Muhammad Ali died June 3, 2016. Eig recalls the day of the funeral when the black Cadillac came for Ali’s coffin, a fitting visual bookend to the story of the man who personified a generation.