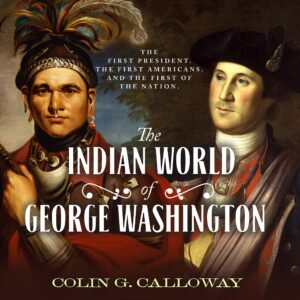

The Indian World of George Washington: The First President, the First Americans, and the Birth of the Nation

On February 22, 1800, the Reverend John Carroll, Catholic bishop of Baltimore, eulogized the recently deceased George Washington, a fellow member of the colonial Chesapeake elite. The prelate stated that Washington’s harrowing adventures within the “inhospitable confines of the savage Indian” provided the indispensable “training and education by which Providence prepared … [him] for the fulfillment of his future destinies.” 1

Those brief comments summarize the essence of what historian Colin G. Calloway elaborates in 492 pages of text in The Indian World of George Washington. Calloway’s tenth book—one of five finalists for the 2019 National Book Award in the nonfiction category—is as compelling and rewarding as his much-honored One Vast Winter Count: The Native American West before Lewis and Clark (2006). Born and educated in the United Kingdom, with a doctorate from the University of Leeds, Calloway worked at the D’Arcy McNickle Center for the History of the American Indian at the Newberry Library in Chicago and taught at the University of Wyoming before becoming the John Kimball, Jr. 1943 Professor of History and Professor of Native American Studies at Dartmouth College in 1995.

The Indian World of George Washington is not a traditional biography dealing with every issue from childhood to death. Instead, “it employs a biographical framework to show how Native America shaped the life of the man who shaped the nation”—presenting “an unfamiliar but more complete telling of what some would say is the American story.” (15) Calloway offers an incisive analysis of Washington’s most significant half-century of Indian relations (1748-1799) employing ethnohistory, a discipline that here integrates Native American cultural perspectives in evaluating Washington’s complete legacy, warts and all. Seven chapters recount his militia service in the French and Indian War; six chapters cover his Revolutionary War exploits; and the last six chapters detail the legacy of his presidency for a complex, multiracial America.

Calloway’s goal “is neither to demonize Washington nor to debunk him. … [His] dealings with Indian people and their land do him little credit, but on the other hand his achievement in creating a nation from a fragile union of states is more impressive when we appreciate the power and challenges his Indian world presented. The purpose is to show how Washington’s life, like the lives of so many of his contemporaries, was inextricably linked to Native America.” (13) “Neither his life nor that of his nation would have developed the way it did without his involvement and experiences in Indian country.” (13)

Calloway exaggerates in claiming that “none” of Washington’s previous biographers “have shown any particular interest or expertise in Indian history.” (4) While he is the most qualified author, I cannot agree that this is “a book aimed at a broad readership” (xv)—precisely because an expansive knowledge of that era is so rare and specialized. Casual readers unfamiliar with the complexities of ethnohistory, the eighteenth-century Chesapeake backcountry, and multi-tribal histories may well find the book too scholarly, too dense, or both. Moreover, there is little “entertainment value” in reading about frontier atrocities, such as the 1752 French attack on Miami Indians, in which Canadian troops killed, boiled, and ate Chief Memeskia or the 1782 massacre of ninety-six unarmed Delaware Indian Christians, including children, at Gnadenhutten, Ohio. All were beaten to death, scalped, and burned by American militiamen. (275)

For the right readers, Callaway does an excellent job of linking Washington-the-surveyor’s intense pursuit of profitable real estate with the self-serving decisions he made as a military commander, treaty negotiator, and chief executive of the new American nation.

For the right readers, Callaway does an excellent job of linking Washington-the-surveyor’s intense pursuit of profitable real estate with the self-serving decisions he made as a military commander, treaty negotiator, and chief executive of the new American nation. Washington actually admitted that “a great and lasting War can never be supported on this principle [of patriotism] alone. It must be aided by a prospect of Interest or some reward.”2 That reflected his gentry lineage, profession as a surveyor, and investments in military land bounties. Lucky timing facilitated Washington’s insatiable appetite for profits and power derived from former Indian territories.

His first advantage in gaining the wealth and status of a Virginia gentleman derived from his great-grandfather, John Washington, “The Immigrant,” who claimed Potomac River lands by conquering nearby Indians. Both he and his great-grandson were called “Conotocarious” (“Devourer” or “Destroyer of Villages”) by Indians who lost tribal homelands (25) to such surveyors using a special compass they called a “land stealer.” (37-8) Luckier still, at age eleven, George survived smallpox and then inherited a Rappahannock River plantation when his father died from that disease. Soon after, he acquired Mount Vernon following the successive deaths of his older brother, Lawrence, in 1752, his niece, Sarah, in 1754, and the remarried widow of Lawrence in 1761. (4)

In 1750, eighteen-year-old Washington began his career as a surveyor in the Shenandoah Valley, patenting nearly 1,500 acres for himself. He completed forty-five additional surveys in western Virginia, acquiring 65,000 more acres in thirty-seven different locations. At his death, he still owned 52,000 acres in six future states. (40) His penchant for property made him an “aggressive expansionist” who enhanced America’s “identity as a nation built on Indian land.” (12) Virginia was in the forefront of western expansion across a “mosaic of tribal homelands and hunting territories,” which later required “multiple foreign policies, competing agendas, and shifting strategies” by the new national government. (5)

When rampant indebtedness and insolvency threatened the political power and social status of elite Tidewater gentry, Washington refashioned himself as a self-made military “commander” during the French and Indian War. His performance, however, was woeful and tragic, including his “assassination” of sleeping French troops in May 1754; the humiliating surrender of his garrison at Fort Necessity in July 1754; his failure to anticipate the ambush of General Braddock’s army in July 1755; and the slaughter of Virginia militiamen from the friendly fire of troops he commanded in November 1758, resulting in fourteen killed and twenty-six wounded.

His [Washington’s] penchant for property made him an “aggressive expansionist” who enhanced America’s “identity as a nation built on Indian land.”

“Indians were of central importance in Washington’s world, but for most of his life he operated on the peripheries of theirs.” (9) Still, he met a wide variety of prominent Indian leaders, especially during wartime, including Tanaghrisson (the Seneca “Half King”), Shingas (Delaware war chief), and Scarouady (the Oneida “Half King”). But he distrusted less elite “Barbarians” (132) and encouraged the payment of Indian scalp bounties, with each one worth three months income for a lower class colonist. (130) Even after many experiences in the backcountry, however, Washington “never learn[ed] how to defeat the British in the Revolution by fighting in the Indian style.” (167)

With the Revolution won, President Washington was “knee-deep in intertribal, intratribal, and interpersonal politics.” (413) He had to “look east to the past and west to the future. And when he faced west, he faced Indian country.” (14) “American history has largely forgotten what Washington knew”—that “Indian lands were vital to the future growth of the United States, but … he also knew that Indians were vital to the national security … of the fragile republic.” (3) “The settler colonial society he represented grew from one held back by Indian power and anxious for Indian allies to an imperial republic that was on the move, dismantling Indian country to create American property, and dismantling Indian ways of life to make way for American civilization.” (483)

“Fighting, fearing, and hating Indians had helped forge a common identity among white peoples before; now the shared experience of Scots, Irish, Germans, English, and others in fighting and dispossessing Indians helped forge a common bond as Americans. Washington disparaged unruly frontier folk as disturbers of order and tranquility, but by harnessing their aggressive expansionism, the government created a new, racially defined empire and a nation of free white citizens that excluded Native Americans.” (12)

The president “never questioned that Indians … would relinquish their lands to the growing republic.” (484) But during his two terms, “instead of changing and ceasing to be Indians, they changed and continued to be Indians. Instead of abandoning their traditions, cultures, and values, they built on their Native American past to give themselves an American future.” (490) The most elite western land speculator in the highest political office set the nation “on a path of expansion” that “also opened the way for slavery to move west.” (482-3) Since only whites would benefit from dispossessed Indians and enslaved blacks, President Washington hoped to leave office on a “unifying note” by making “slavery and Indian policy … conspicuously absent from [his] … Farewell Address.” (482)

One issue ignored in this large, informative book should concern St. Louisans the most. The French families that founded St. Louis and helped it prosper in fur trading with supportive and talented Osage warriors believed that their superior civilized society was threatened by violent Americans moving ever closer. In the 1750s, Washington himself had briefly considered partnering with Indians in a western Virginia fur trade before deciding that the sustained presence of “savages” would scare off prospective white purchasers of his lands and cost him profits. Forty years later, the remnants of tribes ravaged by Washington’s warfare in the Ohio Country found refuge in southern Missouri and signaled dark days ahead for Indians and their white friends if the United States ever controlled the trans-Mississippi West. Prejudicial American attitudes about “savage-loving” French “papists” did indeed infect St. Louis when military veterans of Washington’s Virginia brought American culture to town and throughout tribal homelands.