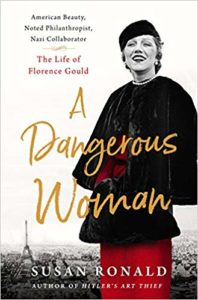

A Dangerous Woman: American Beauty, Noted Philanthropist, Nazi Collaborator—The Life of Florence Gould

In her twenties, Florence Gould danced in the Folies Bergere. In her thirties, she dazzled her guests in sequined pajamas designed for her by Coco Chanel. In her forties, during WWII, she served as a collaboration grande horizontale for high-ranking Nazis in Paris. In her fifties, as the war ended, she schemed with them to launder their money. That triggered an investigation for treason by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. She died unrepentant in her late 80s. Susan Ronald details Florence’s wild ride of a life in A Dangerous Woman: American Beauty, Noted Philanthropist, Nazi Collaborator—The Life of Florence Gould.

Born 1895 in San Francisco to French immigrants, Florence Lacaze and her mother fled to Paris after the 1906 earthquake. Her mother planned to launch her child as an opera star, or a courtesan like a character by Colette, or the wife of a very rich man.

Being a showgirl brought the attention she craved, but not the lavish lifestyle.

What Florence lacked in musical talent, she made up in beauty: hypnotic green eyes, long blonde hair, and a lush figure she emphasized with her signature vampish walk. That led to the chorus line at the Follies-Bergere where she danced with her lover, Maurice Chevalier. Being a showgirl brought the attention she craved, but not the lavish lifestyle.

That changed when she met Frank Gould, 18 years her senior, and ultra-rich thanks to his financier father, Jay Gould, who left an estate worth four billion dollars in today’s money. Frank owned Chateau Le Robillard, once the home of Dumas’s musketeer, d’Artagnan, where he stabled his racehorses and lived like a French nobleman. A drunken nobleman. He would awaken at 8 a.m., drink a quart of whiskey and go back to sleep. At dinner, he drank until he passed out.

Florence wanted Frank to get well so they could become the It couple of beau monde Paris, which existed in “a world somewhere between Guermantes Way and Sodom,” quipped one aristocrat.[1] “Everybody slept with everybody else. It was fun. It was practical,” Florence said. Marriage in 1923 did not change old habits. Florence and Frank discussed their trysts at the breakfast table.

Florence “had yet to meet a man she could not control,” said Ronald. Her secret: “To hold on to your man, you need to occupy him. You make love together for, what? An hour? Then you have 23 other hours to fill.” She imagined she and Frank running an empire of pleasure palaces along the French Riviera. They scouted locations between Nice and Monte Carlo. They ultimately amassed 50 hotels/casinos across France catering to the ultra-rich. Casinos are a cash operation, which allowed the couple to rake in lots of money.

Not everyone helped them in their quest. One landowner refused to sell to Frank because he was an American. Florence retorted, “Money doesn’t care who owns it.”

Frank stayed in the background handling the finances, letting his wife beguile their famous guests, Zelda and Scott, Rudolph Valentino and Harpo Marx, and Hemingway. Her talent and charm for making important friends went unrivaled. She knew entertainment, helping launch the “Jazz at the Juan Festival” and popularizing water-skiing.

She smelled opportunity when the Depression reached France, snapping up Impressionist paintings and fine jewels at bargain prices.

Frank stayed in the background handling the finances, letting his wife beguile their famous guests, Zelda and Scott, Rudolph Valentino and Harpo Marx, and Hemingway. Her talent and charm for making important friends went unrivaled.

Florence could now achieve her dream of being a Paris salonniére, exchanging witticisms with artists and aristocrats like a modern day Madame de Stael. Her guests included Picasso, Matisse, Kandinsky, Klee, Duchamp, Max Beckmann, Man Ray, D.H. Lawrence, and Colette. But, author Ronald notes, while Florence knew much about big-name writers, she was not familiar with their work.

By 1933, the Goulds’ two largest casinos were losing money. Three fires broke out at the same time in three different parts of one hotel. Rumor had it the Goulds were behind the fortunate fire which destroyed the records. The French authorities investigated them. Florence did what she had to do with the authorities and charges were never filed.

“I have slept with the Dear Lord,” she said, “and the Dear Lord loves me.”

When the Nazis goose-stepped through the streets of Paris, Frank and Florence could have fled to the United States. They did not because it would have cost them millions of dollars. Frank had left decades earlier to avoid paying federal income taxes. To hold onto their French property during the Occupation, they needed Florence’s Gestapo contacts. Her new lovers provided her with the inside information she needed. She was now overseeing their empire as Frank’s mental facilities faded.

She and a friend organized a network of socialites in a high-class prostitution ring catering to top Nazi officials for black market goods. She juggled bedmates—Helmut Knochen, the top Gestapo commander of Paris, and his boss, SS leader, Carl Oberg, who deported 40,000 French Jews.

She took as her main lover an SS agent, Ludwig Vogel, who was younger than she by 14 years. He oversaw the French deportations, and Operation Todt, a mass slave labor organization. He could procure whatever Florence desired for her salon on the black market: butter, eggs, fresh vegetables, coffee, chocolate, meat, and coal. While Parisians burned their furniture and floorboards during the bitter winters, 18-ton trucks delivered coal to Florence. Her salon surpassed all others with feasts. It was said that they became less literary and more like an orgy.

Vogel also secured for Florence a huge 8-room apartment near his in the posh 16th arrondissement. It had belonged to a wealthy Jewish family. Florence did not care. It was an “anything goes” occupation. When the Germans began looting art from Jewish collectors, Florence bought their pieces at auction. Even her friends labeled her an anti-Semite.

More was never enough for Florence and her ultra-rich friends.

She twice flew to Germany with Vogel while he inspected Luftwaffe airfields. She did not pass on the information to her occasional lover, the American ambassador to Vichy France, William C. Bullitt, or her acquaintances in the resistance.

When the Germans began looting art from Jewish collectors, Florence bought their pieces at auction. Even her friends labeled her an anti-Semite. More was never enough for Florence and her ultra-rich friends.

When it became clear that the Axis powers were losing, Nazi high commanders began moving their money to foreign banks. Florence became a silent partner and, as a principal of the bank, transferred 5 million francs to Banque Charles in Monte Carlo before D-Day.

The liberation of Paris in August 1944 triggered the purge of collaborators: Women who had slept with the enemy had their heads shaved and were paraded in the streets. Others were marched naked and beaten. Not Florence. Buoyed by her money and her contacts, she floated above retribution. She never showed any remorse.

Instead, she presented herself as a victim of the Occupation. She told the Allies she had only invested in Banque Charles to save her husband. The French authorities did not believe her and continued their criminal investigation. They requested that she be deported. She was not.

The Americans began investigating her for treason, the moving of Nazi money to Monte Carlo. They also wanted to know how she managed to get Vogel released from prison and flown to America. J. Edgar Hoover sent her treason file to the U.S. Attorney General. And her friend, U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morganthau, began investigating her for war profiteering.

Florence hired a first-rate lawyer, and the feds moved onto larger targets. The cases against her were never formally closed.

She continued throwing lavish parties at her salon, telling guests she had joined the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA) in late 1943, as a resistant.

She began writing bigger checks to charities. She walked the red carpet at the first Cannes Film Festival. As her looks faded, she bedecked her walls with more Impressionist paintings and adorned herself with more impressive jewels.

Frank died in 1956 and his twin daughters declared war on their stepmother. One sent Hoover new information in the treason case: Florence had worked with the Nazis to resurrect the Third Reich with the Gould real estate as part of the plan. Nothing came of that accusation.

Like others of her ilk with ill-gotten gains, she laundered her reputation by becoming an arts philanthropist. She contributed so many millions the French awarded her their Legion of Honor.

As Frank’s main heir, Florence partied on with Princess Grace and the Aga Kahn.

Like others of her ilk with ill-gotten gains, she laundered her reputation by becoming an arts philanthropist. She contributed so many millions the French awarded her their Legion of Honor. Thomas Hoving, then director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, threw her a private dinner for her donation. She established a cultural foundation in her name. She died in 1983, the patron of largesse.

As Americans ask that institutions change the names of buildings named for slaveholders and the manufacturers of opioids[2], the issue of toxic gifts could emerge in arts philanthropy.

The Forward newspaper published an article, “Should Arts Venues Honor a Nazi Hostess?” in 2011. Benjamin Ivry wrote, “The question as to whether the Foundation’s money is tainted, remains open.” [3]