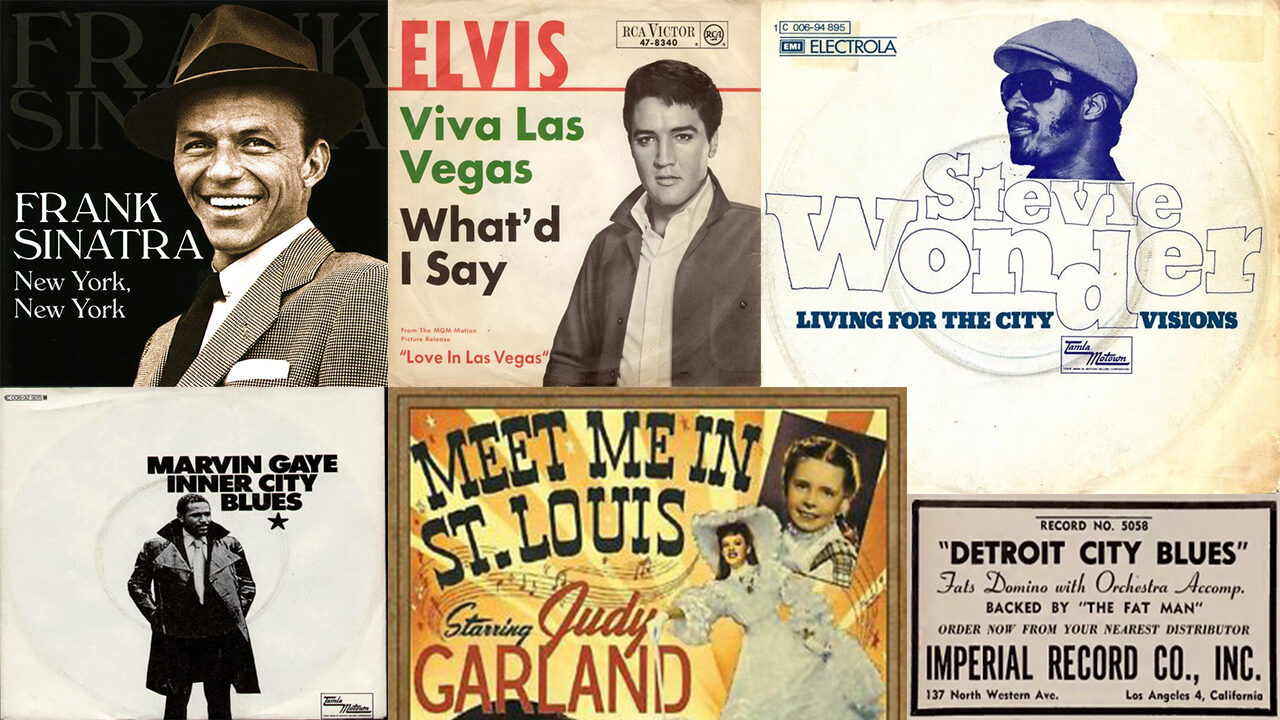

No one is more associated with singing songs about cities than Frank Sinatra, the Chairman of the Board, and considered by many America’s greatest popular singer. Sinatra as a stylist could be tender, humorous, forlorn, sincere, spritely, even arty, but he is especially known for a certain kind of swinging swagger and this is what he brings to his city songs, all of which were significant hits for him: (1) “New York, New York” is the theme song from Martin Scorsese’s musical of the same name. Written by Fred Ebb and John Kander, Liza Minelli sang it in the film. Others have sung it as well but Sinatra’s version of this tune about leaving the small town to make it big in NYC is the version everyone knows. It was a Top Forty hit, peaking at 32 in 1980. It became Sinatra’s signature tune. (2) “Chicago, That Toddling Town” and “Chicago, My Kind of Town” are Sinatra’s two noted songs about the Windy City. His versions of both of them are more famous than anyone else’s. The first was written in 1922 by Fred Fisher and the second is by Jimmy Van Heusen and Sammy Cahn. Sinatra sang the latter song in the mediocre 1964 musical, Robin and the Seven Hoods. (There is a nice dance sequence with Sammy Davis, Jr. and Bing Crosby, Sinatra, and Dean Martin doing a wonderful rendition of the Sammy Cahn/Jimmy Van Heusen song, “Style.”) Both Chicago songs charted for Sinatra. (3) “LA is My Lady” from the Sinatra of the same name, released in 1984. It was written by Alan and Marilyn Bergman, Quincy Jones, and Peggy Lipton Jones. Jones produced this album, and the song feels like a Jones song, probably because of the arrangement. This was meant to be smoother Sinatra here, a kind of Miami Vice-like Sinatra. The song was a moderate hit as was the album. Once again, Sinatra’s version of the song is better known than anyone else’s. But this song never achieved the status of “New York, New York” or the Chicago songs. On the other hand, the fact that Jones had Sinatra do the song was an indication that everyone understood, public in the music industry and the general public, that one of Sinatra’s trademarks was being able to do anthems about cities with a unique conviction.

Frank Sinatra circa 1955.

The theme song from Elvis Presley’s (4) “Viva Las Vegas” (1964) is, along with “Jailhouse Rock,” his most famous movie song, among his most memorable, to be sure. Presley never sounded better than doing this song, with a remarkable combination of heat and cool. He makes Las Vegas sound like a place any young person would want to be: well-lit and never-ending glamor and exhilaration. Written by the legendary Brill Building team of Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, others have done this song, but Presley’s version is the one everyone knows.

If there is one popular song in the English language that serves as the great paean to the city and urban life, it has to be British singer Petula Clark’s “Downtown,”(5) composed by Tony Hatch, a monster hit in 1964 and covered by many singers. Here is a song that tells of the glory of the city, not as a place of alienation or loneliness but as a place of companionship and community in the area called downtown. The song also skillfully suggests the necessary link between commerce and community, business as a way of bringing people together. What is striking is that the song was a major hit when urban downtowns were deteriorating, as city cores themselves were starting to fall apart. Suburbanization, the rise in crime, the tense urgency of racial politics, the mistakes of urban renewal, the expansion of car ownership all conspired against the traditional urban downtown. The popularity of the song was, in part, due to its beautiful, well-constructed melody and its finely wrought lyrics, but also because it came out right as downtowns were entering their twilight, so the song evoked the dying but still-brilliant glow of the present with nostalgia for the end of an era.

If there is one popular song in the English language that serves as the great paean to the city and urban life, it has to be British singer Petula Clark’s “Downtown,”(5) composed by Tony Hatch, a monster hit in 1964 and covered by many singers. Here is a song that tells of the glory of the city, not as a place of alienation or loneliness but as a place of companionship and community in the area called downtown. The song also skillfully suggests the necessary link between commerce and community, business as a way of bringing people together. What is striking is that the song was a major hit when urban downtowns were deteriorating, as city cores themselves were starting to fall apart. Suburbanization, the rise in crime, the tense urgency of racial politics, the mistakes of urban renewal, the expansion of car ownership all conspired against the traditional urban downtown. The popularity of the song was, in part, due to its beautiful, well-constructed melody and its finely wrought lyrics, but also because it came out right as downtowns were entering their twilight, so the song evoked the dying but still-brilliant glow of the present with nostalgia for the end of an era.

Record producer/songwriter/arranger extraordinaire/convicted murderer Phil Spector provides us with one of the most melodramatic, overproduced masterpieces of early 1960s’ Top Forty pop with “Uptown” (1962) by the Crystals, an African-American girl group that enjoyed some considerable success with Spector with “Da Do Run Run,” “He’s a Rebel,” and “There’s No Other Like My Baby.” “Uptown” was written by Brill Building wizards Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann. The song has a girl singing about her boyfriend who is nothing when he is downtown but when he comes uptown to his girlfriend’s “tenement,” “where folks don’t have to pay much rent,” which is certainly not true, “he’s a king.” The song has castanets and a flamenco guitar, in addition to a full orchestra with strings. How these poor girls were able to perform this song in person at a rock and roll show with a five-piece band and no echo effect is beyond me! I am sure they found a way. The boyfriend is, of course, a member of a racial minority, Black or Puerto Rican. The song is sung by Black singers so the tendency is to think the boy is Black but all the “Spanish tinge” in the song, to borrow an expression from Jelly Roll Morton, makes me think it is about a Puerto Rican. In fact, the Crystals themselves sound a bit like Hispanic girl singers on the record. (They clearly sing the lyric, “The world is sweets/is at his feets/when he’s uptown.” So, as a kid, I thought they were “Spanish” girls singing in their second language.) In any case, the song dramatizes class and racial segregation and stratification in the city (clearly, New York), spiked with a bit of social consciousness, as it is called, while also giving its girl teen-aged audience the type of teen love song that they craved.

Gil Scott-Heron’s (6) “Johannesburg” from his 1975 album, From South Africa to South Carolina, did as much to spark the divestment  movement as any piece of art could. It was a moderate hit, but the song was something of an anthem in some circles. Of course, the song is less about the city as a city and more about what the city is politically. It stands in for South Africa itself and comes as close to advocating violent revolution as a song is likely to get. It is, along with “The Bottle” and “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” among Scott-Heron’s most popular songs.

movement as any piece of art could. It was a moderate hit, but the song was something of an anthem in some circles. Of course, the song is less about the city as a city and more about what the city is politically. It stands in for South Africa itself and comes as close to advocating violent revolution as a song is likely to get. It is, along with “The Bottle” and “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” among Scott-Heron’s most popular songs.

“I Left My Heart in San Francisco” (7) is Tony Bennett’s signature tune. It was written by George Cory and Douglass Cross in 1953 in, ahem, New York and is rather in spirit like Stuart Gorrell/Hoagy Carmichael’s 1930 song, “Georgia,” about someone missing his/her home. Bennett’s version was a big hit in 1962. It is probably the song he is most associated with.

“Dancing in the Street” (8) by Martha Reeves and the Vandellas is, in one respect, typical of teenage rock tunes of the 1960s that call out the names of cities likely to be on the tour of the performing group. But no tune like this has a book devoted entirely to it: Ready for a Brand New Beat: How “Dancing in the Street” Became an Anthem for a Changing America by Mark Kurlansky (2013). This 1964 tune was considered by many young Blacks the song of the revolution, the ultimate song of urban America. It became such when urban race rebellions became commonplace in the summers of the 1960s. When Martha Reeves first heard of this interpretation of the song while performing on the Motown Revue tour, she was shocked. “It’s a song about dancing,” she said. This was Marvin Gaye’s favorite Motown tune (he, along with William “Mickey” Stevenson and Ivy Jo Hunter, wrote it). He also played the drums on the recording. Maybe Gil Scott-Heron was right. The revolution will not be televised. It will be broadcast over the transistor radios of finger-popping Black teenagers. Later, Marvin Gaye would record a grittier city song, “Inner City Blues,” (9) about Black urban life on his acclaimed album, What’s Going On. Before we leave Detroit, let us consider John Rich’s “Shutting Detroit Down” (10) from his 2009 album, Son of a Preacher Man, a sort of populist country song that recalls the spirit of Woody Guthrie, speaking up for the proles being laid off in dead American cities while huge corporations get government bailouts, as it is called “welfare for the rich.” Co-written with John Anderson, the song was written after watching a news broadcast, depicted in the video, much in the way folksinger Phil Ochs took his songs from the newspapers. The drama here about the White working-class ultimately poses the question of the political solution to the problem: is it Donald Trump or is it Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez? And Fats Domino (The Fat Man), on a simpler note, wants you to know that Detroit is “the finest city in this world” in his 1949 recording, “Detroit City Blues.” (11) The reason: the women. Apparently, the women in Kansas City are something else as you will learn further down this list. I suppose the Domino was sincere, even though the song was recorded in New Orleans, his hometown.

“Dancing in the Street” (8) by Martha Reeves and the Vandellas is, in one respect, typical of teenage rock tunes of the 1960s that call out the names of cities likely to be on the tour of the performing group. But no tune like this has a book devoted entirely to it: Ready for a Brand New Beat: How “Dancing in the Street” Became an Anthem for a Changing America by Mark Kurlansky (2013). This 1964 tune was considered by many young Blacks the song of the revolution, the ultimate song of urban America. It became such when urban race rebellions became commonplace in the summers of the 1960s. When Martha Reeves first heard of this interpretation of the song while performing on the Motown Revue tour, she was shocked. “It’s a song about dancing,” she said. This was Marvin Gaye’s favorite Motown tune (he, along with William “Mickey” Stevenson and Ivy Jo Hunter, wrote it). He also played the drums on the recording. Maybe Gil Scott-Heron was right. The revolution will not be televised. It will be broadcast over the transistor radios of finger-popping Black teenagers. Later, Marvin Gaye would record a grittier city song, “Inner City Blues,” (9) about Black urban life on his acclaimed album, What’s Going On. Before we leave Detroit, let us consider John Rich’s “Shutting Detroit Down” (10) from his 2009 album, Son of a Preacher Man, a sort of populist country song that recalls the spirit of Woody Guthrie, speaking up for the proles being laid off in dead American cities while huge corporations get government bailouts, as it is called “welfare for the rich.” Co-written with John Anderson, the song was written after watching a news broadcast, depicted in the video, much in the way folksinger Phil Ochs took his songs from the newspapers. The drama here about the White working-class ultimately poses the question of the political solution to the problem: is it Donald Trump or is it Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez? And Fats Domino (The Fat Man), on a simpler note, wants you to know that Detroit is “the finest city in this world” in his 1949 recording, “Detroit City Blues.” (11) The reason: the women. Apparently, the women in Kansas City are something else as you will learn further down this list. I suppose the Domino was sincere, even though the song was recorded in New Orleans, his hometown.

“Night Train” (12) by James Brown, recorded in 1961, is the most popular vocal version of this song. Basically, tenor saxophonist Jimmy Forrest, a St. Louis native, took a riff from a Duke Ellington tune. (He played in Ellington’s band for a time.) He made more R&B-like and made himself a hit. Lyrics were added but Brown threw out those lyrics and added his own, naming cities as stops on the train’s journey (or his performance tours). Brown liked doing this and would do with other songs such as “Mashed Potatoes, USA” and “Mind Power.” The difference with “Mind Power” was that Brown mentioned the Black sections of cities rather than simply the cities themselves. Lou Rawls was to do this in a famous monologue from 1966 for the song “Tobacco Road.” (13) He was to use a similar monologue, focusing on growing up Black in Chicago for his song, “Dead End Street.” (14) This is certainly a different Chicago than what we get from Sinatra.

“Night Train” (12) by James Brown, recorded in 1961, is the most popular vocal version of this song. Basically, tenor saxophonist Jimmy Forrest, a St. Louis native, took a riff from a Duke Ellington tune. (He played in Ellington’s band for a time.) He made more R&B-like and made himself a hit. Lyrics were added but Brown threw out those lyrics and added his own, naming cities as stops on the train’s journey (or his performance tours). Brown liked doing this and would do with other songs such as “Mashed Potatoes, USA” and “Mind Power.” The difference with “Mind Power” was that Brown mentioned the Black sections of cities rather than simply the cities themselves. Lou Rawls was to do this in a famous monologue from 1966 for the song “Tobacco Road.” (13) He was to use a similar monologue, focusing on growing up Black in Chicago for his song, “Dead End Street.” (14) This is certainly a different Chicago than what we get from Sinatra.

Chuck Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen,” (15) released in 1958, about a girl who wants to go to something like the Sox Hop and dance the night away, gives us a list of cities such as one might find in a rock tune but did not carry anywhere near the political significance that many found in Dancing in the Street, which so flummoxed Martha Reeves. Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys used “Sweet Little Sixteen” for “Surfing U.S.A.”

Speaking of Chuck Berry, “Memphis, Tennessee,” (16) originally released in 1959, is one of his noted songs but here the city is simply a  destination, a place Berry is trying to reach by phone to speak to his daughter which is where Berry’s estranged wife, girlfriend, partner has taken her. The daughter tried to reach him but was unsuccessful. “Memphis, Tennessee” is not about a city as much as it is a little family drama. Johnny Rivers’s 1964 cover was a huge hit. Marc Cohn’s “Walking in Memphis,” (17) released in 1991, on the other hand, is a true, heart-on-sleeve tribute to the city, or at least to its musical history.

destination, a place Berry is trying to reach by phone to speak to his daughter which is where Berry’s estranged wife, girlfriend, partner has taken her. The daughter tried to reach him but was unsuccessful. “Memphis, Tennessee” is not about a city as much as it is a little family drama. Johnny Rivers’s 1964 cover was a huge hit. Marc Cohn’s “Walking in Memphis,” (17) released in 1991, on the other hand, is a true, heart-on-sleeve tribute to the city, or at least to its musical history.

Dave Frishberg is a national treasure, one of the great songwriters and musical wits out there. “Another Song About Paris” (18) is simply hilarious, a clever, drop-dead funny take on writing songs about Paris. Speaking of everyone’s songs about Paris, Cole Porter’s “I Love Paris” (19) has certainly been done to death but it is a classic. Then, we have a song that sounds just like the sort of song one should write about Paris called “Under the Bridges of Paris,” (20) written in 1913 by Vincent Scotto, sung in French by Eartha Kitt and in English by Dean Martin. Finally, lest we forget the legendary Vernon Duke’s “April in Paris,” (21) with lyrics by E. Y. Harburg (of The Wizard of Oz fame). This one has all the clichés that Frishberg satirizes.

Speaking of Vernon Duke, here is his masterpiece, “Autumn in New York,” (22), part of a 1934 show called Thumbs Up, possibly the most poignant song ever written about a city.

And speaking of Broadway shows, the American Tribal Love-Rock musical, Hair (1967) by Gerome Ragni, James Rado, and Galt MacDermot, gave us “Manchester, England,” (23) a song about a city being a kind of aspiration or perhaps a muse. The British popular music invasion of the 1960s had made English cities like Liverpool, Bristol, Leeds, and Manchester a bit romantic in a working-class way. So are foreign movies or foreign movie directors with the young: think Antonioni’s Blow-Up, Visconti’s The Stranger, Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451, Bergman’s Persona and Hour of the Wolf, Fellini’s 8 ½ and Juliet of the Spirits, and Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. Antonioni, Fellini, and Polanski are mentioned in the song.

Stevie Wonder’s mini-reenactment of the African-American Great Migration in “Living for the City” (24) (1973) remains one of the extraordinary songs in his canon and a remarkable take of a country bumpkin who comes to the city.

Bobby Troup

“Route 66” (25) by Bobby Troup, composed in 1946 while Troup (whose wife was singer Julie London) was driving west on Route 66, is one of the most famous road songs ever written. It is also a city song, mentioning several that the singer passes along the way. In this way, it is a catalog song of American cities much like such songs as “Dancing in the Street” and “Night Train.” But it is a more subtle song structurally.

Alas, there have been a number of timeless songs written about New York. One of them is the Adolph Green/Betty Comden song, “New York, New York,” (26) from their show, On the Town. Here is the sequence from the film version of On the Town that features the song. Here the composers perform the tune. (One of the big disappointments with the film version of On the Town is the excision of the lovely song, “Lucky to Be Me.”) Another famous songwriting duo, Rodgers and Hart, composed the classic, “Manhattan,” (27) from the 1925 show Garrick’s Gaieties. It has been performed by everyone, popular singers, jazz musicians, even the Supremes. Here is Mickey Rooney, playing Lorenz Hart, performing the tune in the 1948 biopic of the composing duo, Words and Music. And while we are on the subject of New York, it is worth noting Billy Joel’s 1976 classic, “New York State of Mind,” (28) that has been covered by everyone from Frank Sinatra to Barbra Streisand, a bluesy ballad about a jaded man who misses not simply a city but its attitude, its psychology, how it has shaped his identity and his fate. The title has become a phrase in the culture. Then, there is Bob Dylan’s humorous, autobiographical “Talkin’ New York” (29) about a folksinger arriving in New York, playing clubs in Greenwich Village and unable to get a record deal. Finally, the Ad Libs recorded a big pop teen hit in 1965 with “The Boy From New York City,” (30) written by John Taylor and produced by the R&B and rock gurus, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. The song personified the city as the coolest, hippest boy around. A guy this stylish, this in vogue could only be from New York. “And he’s cute/In his mohair suit. And he keeps his pockets full of spending loot.” You had to have been around in the 1960s to appreciate a mohair suit! It is a great tune most recently covered by the jazz vocal group, the Manhattan Transfer.

If not for Judy Garland and Vincente Minelli, the song “Meet Me in St. Louis,” (31) written in 1904 by Kerry Mills and Andrew B. Sterling in honor of the World’s Fair might be known only to antiquarians. But the 1944 film of the same name, the second most commercially successful film of that year, has assured the city of St. Louis a permanent place in American popular culture. W. C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues,” (32) composed in 1914, is not about St. Louis but is without question the most famous song with St. Louis in the title. St. Louis’s hockey team is named after the song. Handy named the song for St. Louis because it was inspired by a chance meeting, he had with a woman in St. Louis who was deserted by her husband. Her lament, “My man’s got a heart like a rock cast in the sea,” became a central lyric of the song. Structurally, the song is a melting pot with a ragtime structure, blues stanzas, and a tango bridge. It is a fairly sophisticated song and helped to popularize the blues, although few blues tunes are as musically intricate. The video of Bessie Smith, the greatest of all blues singers, performing the song is not only a historic gem of a mini-movie but one of the best renditions of the song.

only to antiquarians. But the 1944 film of the same name, the second most commercially successful film of that year, has assured the city of St. Louis a permanent place in American popular culture. W. C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues,” (32) composed in 1914, is not about St. Louis but is without question the most famous song with St. Louis in the title. St. Louis’s hockey team is named after the song. Handy named the song for St. Louis because it was inspired by a chance meeting, he had with a woman in St. Louis who was deserted by her husband. Her lament, “My man’s got a heart like a rock cast in the sea,” became a central lyric of the song. Structurally, the song is a melting pot with a ragtime structure, blues stanzas, and a tango bridge. It is a fairly sophisticated song and helped to popularize the blues, although few blues tunes are as musically intricate. The video of Bessie Smith, the greatest of all blues singers, performing the song is not only a historic gem of a mini-movie but one of the best renditions of the song.

Let us not forget our cousins to the west. Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, famous R&B and pop composers and producers mentioned above, made sure of that writing the song, “Kansas City,” (33) recorded by Wilbert Harrison. It hit No. 1 on the Billboard R&B chart in 1959.

If Meet Me in St. Louis one of the great movie musicals, New Orleans (1947) is one of the most forgettable, except Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday are supporting players (their characters even marry) and there is the wonderful song, “Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans,” (34) composed by Eddie DeLange and Louis Alter and premiered in this film. DeLange wrote lyrics for Duke Ellington’s “Solitude,” Jimmy Van Heusen’s “Darn that Dream,” (he was a long-time composing partner with Van Heusen) and the lovely but neglected tune, “All This and Heaven Too,” also with Van Heusen. Here is Armstrong’s definitive version of “Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans.” And here is Armstrong and Holiday together from the film. While we are on the subject of New Orleans, let us not forget Gary “U.S.” Bonds’s 1961 rocker that had all the HBCU kids sweating and stomping the dance floor, “New Orleans.” (35) The hardcore primitive, raw nature of the performance is what makes the tune so compelling. Written by Frank Guida and Joseph Royster, it was a hit but not as big for Bonds as “Quarter to Three,” which sold a million copies. Bobby Charles’s strolling rhythm of “Walking to New Orleans” (36) was a big hit in 1960 for the pioneer rock and roll performer Fats Domino, a native of the city.

Birmingham, Alabama, is known to most people, not for its huge cast-iron statue of Vulcan (the largest cast-iron statue in the world) or for being historically central to the American steel industry but the 1963 showdown over integration between Martin Luther King Jr. and his nonviolent civil rights marchers (many of them children) and the city’s viciously racist director of public safety, Eugene “Bull” Connor that resulted in the mind-numbing tragedy of four Black girls being murdered when their church was bombed by White terrorists. At the time of this racial unrest in Birmingham, leftist folksinger Phil Ochs recorded “Talking Birmingham Blues” (37) (released on his 1965 album, I Ain’t Marching Any More), a topical song about a city whose name had become in many quarters synonymous with brutal racism. But recent songs are no more complimentary about recent Birmingham than Ochs was about Birmingham during the height of the civil rights movement. Amanda Marshall’s 1995 song, “Birmingham,” (38) gives us the drama of spousal abuse. The wife screws up her courage to forge a new life and so leaves. In the video, the husband, the stereotypical redneck with wife-beater t-shirt and Confederate flag house décor, helplessly rants at the end when he discovers his wife gone. Ani DeFranco’s “Hello Birmingham,” (39) from her 1999 album To the Teeth, gives us another despairing view of the city by superimposing it on another, in this case, Buffalo, DeFranco’s hometown. The song is a response to the murder of Dr. Barnett Slepian, a Buffalo abortion provider, by an anti-abortion zealot. DeFranco sees the anti-abortion movement in the same light as the segregationist, White supremacist movement that King opposed in Birmingham. (King is, in fact, mentioned in the song.) The song also condemns the impotence of electoral politics. Poor Birmingham cannot escape its highly publicized violently racist past. After all, DeFranco apparently could not find a more compelling analogy that her audience would immediately recognize with which to condemn Buffalo for this murder than to say it is like 1963 Birmingham.

Birmingham, Alabama, is known to most people, not for its huge cast-iron statue of Vulcan (the largest cast-iron statue in the world) or for being historically central to the American steel industry but the 1963 showdown over integration between Martin Luther King Jr. and his nonviolent civil rights marchers (many of them children) and the city’s viciously racist director of public safety, Eugene “Bull” Connor that resulted in the mind-numbing tragedy of four Black girls being murdered when their church was bombed by White terrorists. At the time of this racial unrest in Birmingham, leftist folksinger Phil Ochs recorded “Talking Birmingham Blues” (37) (released on his 1965 album, I Ain’t Marching Any More), a topical song about a city whose name had become in many quarters synonymous with brutal racism. But recent songs are no more complimentary about recent Birmingham than Ochs was about Birmingham during the height of the civil rights movement. Amanda Marshall’s 1995 song, “Birmingham,” (38) gives us the drama of spousal abuse. The wife screws up her courage to forge a new life and so leaves. In the video, the husband, the stereotypical redneck with wife-beater t-shirt and Confederate flag house décor, helplessly rants at the end when he discovers his wife gone. Ani DeFranco’s “Hello Birmingham,” (39) from her 1999 album To the Teeth, gives us another despairing view of the city by superimposing it on another, in this case, Buffalo, DeFranco’s hometown. The song is a response to the murder of Dr. Barnett Slepian, a Buffalo abortion provider, by an anti-abortion zealot. DeFranco sees the anti-abortion movement in the same light as the segregationist, White supremacist movement that King opposed in Birmingham. (King is, in fact, mentioned in the song.) The song also condemns the impotence of electoral politics. Poor Birmingham cannot escape its highly publicized violently racist past. After all, DeFranco apparently could not find a more compelling analogy that her audience would immediately recognize with which to condemn Buffalo for this murder than to say it is like 1963 Birmingham.

Fortunately for Buffalo, it has fared a bit better in the history of popular music than Birmingham. Al Dubin and Harry Warren’s “Shuffle Off to Buffalo,” (40) featured in the 1933 film musical, 42nd Street, is one of the famous Broadway tunes ever written, and “Shuffle off to Buffalo” is a cultural expression meaning to leave, or a way to say that a show has died, or a name for a tap-dance step, or a way to say one is getting married. Buffalo is near Niagara Falls, a popular honeymoon spot and the song is about marriage, slyly mentioning sex and procreation. Here is the song as it was performed in the film. And here is the jazzed-up, vocally innovative version by the Boswell Sisters.

Fortunately for Buffalo, it has fared a bit better in the history of popular music than Birmingham. Al Dubin and Harry Warren’s “Shuffle Off to Buffalo,” (40) featured in the 1933 film musical, 42nd Street, is one of the famous Broadway tunes ever written, and “Shuffle off to Buffalo” is a cultural expression meaning to leave, or a way to say that a show has died, or a name for a tap-dance step, or a way to say one is getting married. Buffalo is near Niagara Falls, a popular honeymoon spot and the song is about marriage, slyly mentioning sex and procreation. Here is the song as it was performed in the film. And here is the jazzed-up, vocally innovative version by the Boswell Sisters.

“El Paso” (41) as described in Marty Robbins’s dramatic 1959 western song, may be more a town than a city but any baby boomer remembers this song as it was a huge hit on both the pop and country charts. Its narrative drive is mesmerizing. It is better than a lot of movies. It is so vivid in its storytelling that one can nearly picture the place. It is sort of in the tradition as a narrative of a song like Jeff Barry and Ben Raleigh’s “Tell Laura I Love Her,” a big 1960 hit for singer Ray Patterson.

Glenn Frey’s “You Belong to the City,” (42) written for an episode of the popular 1980s cop show, Miami Vice, captured not only the feel of that show and the 1980s well but it expressed a kind of technicolor noir aesthetic that made the song’s hook irresistible. It is hard to find a song that so perfectly expresses an aspect of the urban night as both romance, adventure, and loneliness than this one. Here is a song where style is everything, whose superficiality is cunningly fetching. The only other TV cop show of the 1980s whose music was as memorable was Hill Street Blues. Frey played all the instruments on this tune except the saxophone and the drums.

Glenn Frey’s “You Belong to the City,” (42) written for an episode of the popular 1980s cop show, Miami Vice, captured not only the feel of that show and the 1980s well but it expressed a kind of technicolor noir aesthetic that made the song’s hook irresistible. It is hard to find a song that so perfectly expresses an aspect of the urban night as both romance, adventure, and loneliness than this one. Here is a song where style is everything, whose superficiality is cunningly fetching. The only other TV cop show of the 1980s whose music was as memorable was Hill Street Blues. Frey played all the instruments on this tune except the saxophone and the drums.

Singer/songwriter Oscar Brown Jr.’s snappy, hip “Call of the City” (43) is from his 1965 Mr. Oscar Brown, Jr. Goes to Washington live album. Brown’s celebration of urban life here is reminiscent of Clark’s “Downtown” but is simpler in its conceit. The singer here prefers the city to the country because it is more exciting, more risky, edgier, more life-affirming. The song describes urban life in a way that a contented city dweller might see it but also as someone who is unhappy with life in the country might be inclined to imagine it. So, in this song, the city is not simply a preference but an ideal. In this way, the song is a polemic without seeming to be one.

“Eight Miles High” (44) is a 1966 psychedelic rock song performed by The Byrds, a popular band of the period and written by Roger McGuinn, David Crosby, and Gene Clark. Influenced by Indian ragas and new wave jazz, it is the sort of song that when played in person could go on for a while. It was banned from radio play because the lyrics were, in part, about drug use. What is more interesting is the story the song tells about the band visiting London, the flight over being an important part of the story. There is little complimentary said about the visit, about London, or its people. The song’s title refers to how high a plane flies going across the Atlantic. Actually, a plane does not go eight miles high, but this sounded better to the composers than saying six miles high.

“(I’ve Got a Gal in) Kalamazoo”(45) put that Michigan city on the popular culture map in 1942 when the Glenn Miller Orchestra performed in Orchestra Wives, one of the better swing film musicals of the period. Written by Mack Gordon and Harry Warren, it not only hit number one on the Billboard charts but was nominated for an Academy Award in the category of Best Original Song.

“Only in Miami,” (46) recorded by Bette Midler in 1983, composed by Scott Delawanna and Max Gronenthal, sounds a bit conflicted. It is about a girl living in Miami, an immigrant or a refugee, who longs for her native Cuba. The subject is sad, yet the tempo and vocalizing on the tune is upbeat, energetically so. Songs of longing for home do not usually sound like this. It was used in an episode of Miami Vice.

Carnegie Mellon graduate Loudon Wainwright III paid folk homage in 1970 to Pittsburgh (“Pennsylvania’s western daughter”) in “Ode to Pittsburgh.” (47) It refers to several landmarks including the Allegheny River (“let the alleycade roll right along”), the Pittsburgh Pirates (“in the field of Mr. Forbes”), and the Liberty Tunnel (“tubes of liberty).

Billy Strayhorn’s “Take the A Train,” (48) the signature tune of the Duke Ellington band, is about what was once the most famous Black city in the world, Harlem, and its elegant section, Sugar Hill, where people like Ellington lived. Harlem was always something bigger than the city that contained it. This song did not make Harlem famous. It made it a myth.

Billy Strayhorn’s “Take the A Train,” (48) the signature tune of the Duke Ellington band, is about what was once the most famous Black city in the world, Harlem, and its elegant section, Sugar Hill, where people like Ellington lived. Harlem was always something bigger than the city that contained it. This song did not make Harlem famous. It made it a myth.

Coda

I will end with two songs about my hometown, Philadelphia, a city that has produced a great deal of popular music but has not had a lot of music written about it. (Maybe the word “Philadelphia” is too awkward to use in a song, although “Philly” would seem to work well enough.) I have always been disappointed that none of Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky films or M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense (and just about every movie he has made) or Nicholas Cage’s National Treasure had a theme song about Philadelphia as these movies were set and shot in or near the city.

John Coltrane

My family knew Chubby Checker—in fact, his family lived just a few blocks from me in South Philadelphia before he became a singing sensation. He had a string of hits in the early 1960s such as “The Twist,” “Let’s Twist Again,” “Slow Twistin’,” (with Dee Dee Sharp, a South Philly girl), “Pony Time,” “Limbo Rock,” and “The Hucklebuck,” based on the melody of Charlie Parker’s “Now’s the Time” (who says you can’t dance to jazz). Everyone thinks Checker was a one-hit-wonder, but he was not, and he deserves to be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. End of Editorial.

Philadelphia has had its share of jazz musicians who were born there or lived there for a considerable length of time—John Coltrane, Benny Golson, the Heath Brothers, Lee Morgan, McCoy Tyner, Pat Martino, Archie Shepp, and Nina Simone. Sun Ra lived in Philly for several years. Keith Jarrett is from nearby Allentown (60 miles away). Members of my family knew some of these people too.

Philadelphia has had its share of jazz musicians who were born there or lived there for a considerable length of time—John Coltrane, Benny Golson, the Heath Brothers, Lee Morgan, McCoy Tyner, Pat Martino, Archie Shepp, and Nina Simone. Sun Ra lived in Philly for several years. Keith Jarrett is from nearby Allentown (60 miles away). Members of my family knew some of these people too.

Kenny Gamble

My family also knew Kenny Gamble, who started out as the owner of a record shop on South Street in South Philadelphia, which in William Penn’s original plan of the city was its southern-most boundary. Gamble went on to become one of the main architects of the Sound of Philadelphia, the R&B sound that dominated the Black music airwaves of the early and mid-1970s.

South Street was, when I was a boy, the main shopping and entertainment thoroughfare for Blacks who lived in South Philly. The Black movie house I went to in my childhood was the Royal Theater located at 16th and South Streets. Some of the important jazz clubs were on this street as well as clothing and furniture stores. There were also shops where one could buy roots, herbs, potions, dream books, voodoo spells, and the like. None of this is true anymore. South Street was gentrified in the 1970s. It has a Starbucks, a Whole Foods, and vegan restaurants and bakeries. Black people, for the most part, do not live there anymore.

In 1963, when Black people were still there, the Orlons, a mixed group of three girls and one boy, recorded a tune for Cameo-Parkway Records, the same company that recorded Chubby Checker among others, called “South Street,” (49) in honor of the location. It became a big hit. The first video of the song shows teenagers dancing on American Bandstand, the popular dance show hosted by Dick Clark that was shot in Philadelphia at 46th and Market Streets during the 1950s and 1960s, and the other shows photos of the Orlons. The lyrics were written by Kal Mann, one of the owners of Cameo-Parkway Records, the music was by Dave Appell, who led the house band at Cameo-Parkway.

Bruce Springsteen’s touching theme song for the 1993 film Philadelphia is called “The Streets of Philadelphia.” (50) The video shows a city that seems a little down on its luck. Perhaps this was done to reflect the situation of the character Springsteen sings about, a lawyer (played by Tom Hanks) who is dying from AIDS, is fired from his job, and has hired a lawyer (Denzil Washington) to sue the firm he worked for. I am always moved when I see this video, by the song but not just by the song. I recognize a lot of those streets.

Bruce Springsteen’s touching theme song for the 1993 film Philadelphia is called “The Streets of Philadelphia.” (50) The video shows a city that seems a little down on its luck. Perhaps this was done to reflect the situation of the character Springsteen sings about, a lawyer (played by Tom Hanks) who is dying from AIDS, is fired from his job, and has hired a lawyer (Denzil Washington) to sue the firm he worked for. I am always moved when I see this video, by the song but not just by the song. I recognize a lot of those streets.

Addendum: Forgotten Odds and Ends

Joe Pesci’s short-lived (nine episodes) 1985 detective television series, Half Nelson, produced two songs about Los Angeles, the opening theme, “LA, You Belong to Me,” and the closing song, “LA is my Home,” performed by Dean Martin, who also appeared in the show. “L.A., You Belong to Me,” composed by Stu Phillips and Robert Jason and performed by Jason, is a fairly typical bouncy, synthesized theme song for an ’80s comedy/drama cop TV show that considered itself hip. “L.A. is my Home,” (written by Jack and Jackie Latimer), is more laid-back, with the casual swing of which Martin was the master. Here, at the end of his career, his voice sounds more lived-in, more worldly-wise, an earned and paid-for coolness. He is no longer the lazy singer who simply imitated Bing Crosby but a master stylist in his own right. There are some clever lyrics as well:

We can dress up or hang loose

We even have a Spruce Goose.

If you don’t like the view

Don’t call us, we’ll call you.

The song was among the last that Martin would record in his career and although released as a single, it never charted.

Oscar Brown Jr.’s “Summer in the City,” from the same 1965 album and the same live performance that produced “Call of the City.” Stylistically, “Summer in the City,” more languid and bluesy, serves as a complement to “Call of the City.” The song is about lovers walking in the city on a summer night:

City people, city sights

Busy streets on sultry nights

It’s all so wonderful, strange, and pretty

You and love and the sprawling city

A friend brought to my attention Frank Sinatra’s 1967 version of Lee Hazelwood’s “This Town,” a different sort of city song than the ones Sinatra was most identified with but it is in keeping with the sort of songs Sinatra liked at a certain stage of his career, a sort of big anthem of self-assertion. Instead of taking on the city or conquering the city, “This Town” is about leaving a hard, cruel city. But for Sinatra the singer, the departure is not an admission of defeat but a gesture of defiance. There are better towns, the song implies. Nancy Sinatra, who worked closely with Lee Hazelwood in the 1960s—he wrote her big hits “These Boots are Made for Walking” and “Summer Wine”—performed “This Town” on her 1967 television special. Hazelwood also wrote “Houston” which was a commercially successful tune for Dean Martin.

Dyke and the Blazers had a significant 1967 R&B hit with “Funky Broadway,” although Wilson Pickett’s cover was the much bigger version commercially. Arlester Christian, the band’s leader, is credited as composer. It was the first R&B to use the word “funky,” which was considered by some an obscene word at the time, referring, according to some, the smell of sexual intercourse. (Jazz pianist Horace Silver wrote “Opus de Funk” in 1953 and the term was used among Black jazz musicians to describe a particularly earthy, lowdown sound.) In any case, funky Broadway is a kind of expressionistic synecdoche for Black city life: the street, the crowd, the woman, the nightclub, the bank, and the dance are all part, not of Broadway, but of the Funky Broadway. The song popularized the word “funky” as it entered common American slang.

Having mentioned Horace Silver, I should point out that jazz pianist Bill Evans’s “NYC’s No Lark” might be a commentary on the city but it is also something of an ironic tribute to pianist Sonny Clark. Evans used Clark’s name as an anagram to create the title of the song. What jazz musician ever felt anything but ambivalent about NYC, the mecca of jazz. A beautiful piece of lyricism and dissonance, it is featured on Evans’s Conversations with Myself (1963).

Finally, I would be remiss without mentioning Mahalia Jackson’s two famous songs about Jerusalem, the city of cities for Christians: “The Holy City” (1960 with Percy Faith) and “Walking to Jerusalem” (1963, Greatest Hits album). Many critics and fans consider Jackson the finest of all-female gospel singers, but she might arguably have been the best gospel singer period. She was my mother’s favorite singer. I do not know how many times my mother watched the end of the second version of Imitation of Life (with Lana Turner and Juanita Moore) when Mahalia Jackson sings at Moore’s character’s funeral. My mother was always near tears each time she saw it. Jerusalem or, more precisely, the New Jerusalem, is the city of God for Christians. Don McLean’s Jerusalem would suggest that it is the city of the monotheistic God and where all roads lead. He identifies it as the meeting point of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. But what does the metropolis of God look like? Is Christianity the imaginative journey from the Garden of Eden to the City of God, the last the title of Augustine’s most important treatise? “The Holy City,” a hymn from 1892 composed by Michael Maybrick and Frederic Weatherly, is the sort of pious, stately hymn that one would imagine Faith arranging, with a large choir and Jackson displaying her chops like a magnificent cathedral’s architecture. “Walking in Jerusalem” is a strictly Black church, straight-up gospel tune written by Jackson herself. She will walk and talk in Jerusalem, she sings, arriving there on the ship of Zion. That sort of imagery was mother’s milk for many Black Christians. My mother believed in the New Jerusalem. I am sure she made it to God’s city. I hope to see her there, but it will be a more arduous road for me. The Jerusalem journey is No Lark.