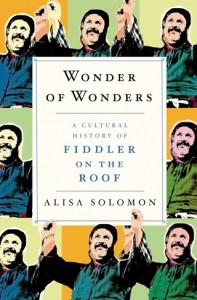

“Musicals always unfold in fake places,” writes Alisa Solomon in Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of Fiddler on the Roof. And no such “fake place” has carried the historical and cultural burden borne by the “little village of Anatevka,” home to Tevye the milkman, his wife Golde, their five daughters, and a motley host of others in the 1964 Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof.

Anatevka and the Jews who live there have been embraced by audiences worldwide. The standard line on Fiddler’s “universality” comes from a Japanese producer, who supposedly commented of the show, “It’s so Japanese.” Solomon adds to this lore, quoting arranger Bobby Dolan telling director Jerome Robbins, “as you must know, these Jewish people are equally Irish.” But “gentiles…gushing over [Fiddler’s] ethnic familiarity” is not the story Solomon offers the reader of this deeply researched book. Instead, Solomon focuses tightly on Fiddler’s “talismanic power to endow an event or object with a warm glow of Jewish authenticity.” A more specific subtitle to her book might be: A cultural history of Fiddler on the Roof and Jewish identity in the 20th century.

Solomon’s approach answers several needs in relation to both Fiddler and scholarly assessment of the Broadway musical. Previous books on the show have not taken its Jewishness as a primary theme. By juxtaposing Fiddler’s sources (in Yiddish literature and theater), Fiddler’s makers (in the midst of personal journeys as Jews), and Fiddler’s reception (in culturally and historically contested locations such as Israel, Poland, and Brooklyn), Solomon offers a mural-like treatment of the Broadway musical as a form both shaped by and shaping Jewish history and identity. Especially valuable is her exploration of the Jewish artists who leveraged the creative sphere of the American musical stage to both escape from and, in the case of Fiddler, celebrate their Jewish selves. By taking Jewish identity as the lens through which to view Fiddler, Solomon’s book enriches our understanding of the historical commonplace that most of the makers of the Broadway musical happened to be Jewish Americans.

Wonder of Wonders is really three books in one. Part one—perhaps a bit long for readers impatient to get to the musical— surveys the making and remaking of the “ground on which Fiddler stood”: the Tevye stories of Sholem-Aleichem. A long first chapter on Sholem-Aleichem frames “the Yiddish Mark Twain” as both literary man and man of the theatre. Solomon chronicles his failure to write a hit for New York’s Yiddish theater and pinpoints the moment—ironically upon the author’s death—when the world of the shtetl Sholem-Aleichem re-created in his stories became a widely “useable Eastern European Jewish past.” Small, majority Jewish towns in Eastern Europe, the shtetls were wiped out by repressive governments, war, and the Holocaust. Well before World War II, Sholem-Aleichem’s stories carried the memory of a rapidly disappearing old world for Jews who fled, many coming to America, some—like Irving Berlin, whose Russian shtetl home was burned to the ground when he was 4 or 5—into careers as the makers of American popular culture. After the Holocaust, as Solomon’s chapter two demonstrates, Sholem-Aleichem’s stories continued to play a key role in efforts to remember a now irretrievably lost Jewish world, even if Tevye as the star of a Broadway musical “had to cool his heels in the assimilating wings [during the 1950s] before striding onto the Broadway stage.” Solomon closes part one with a striking reading of how Exodus, a best-selling book (1958) and blockbuster film (1960) celebrating the founding of the state of Israel, laid the final foundations for Fiddler. She writes, with “Israel as an answer to the Holocaust … depictions of the people of the shtetl [took on] a newly, and nostalgically, noble purpose.” In short, Paul Newman as the “brave and brawny Ari Ben Canaan,” the hero of the film Exodus who emerges shirtless from the waters of the Mediterranean, “made mainstream culture safe for Tevye the Dairyman” to sing and dance his way into Broadway history.

Part two—at almost 150 pages, it’s the length of a short book—recreates the making of the musical in great detail. Solomon’s account draws on archival documents and scores of interviews and reads as a compelling human interest story: the creation of a Broadway hit by well-known creative individuals, several of whom experienced the making of Fiddler as a remaking of their Jewish selves. The most startling portrait to be found here is Jerome Robbins. As Solomon tells it, Robbins was the perfect choice as director, choreographer, and guiding creative force for a Broadway staging of the shtetl. Like Tevye, Robbins’ father Harry left his shtetl to come to America. And on one occasion, Jerome, not quite 6 years old, was taken back to his father’s hometown (Rozhanka, near Warsaw) to visit his grandfather for the summer. On a dance company tour in Poland in 1959, a few years before work on Fiddler began, Robbins went in search of Rozhanka, which, like the shtetls and the Jews who lived there, was long gone. Robbins and the rest of the creators of Fiddler would recreate that world as the “tumble-down, workaday…intimate, obstinate Anatevka,” a Broadway shtetl that would provide Fiddler’s audiences with “nostalgia for a place [they] had never actually been.” Robbins, at two impressionable moments, had been there or tried to go back.

Robbins approached the making of Fiddler as a historical research project drawing on the living traditions of New York City’s Hasidic communities. Solomon reconstructs his path through this world, to the point of identifying the Hasidic wedding performer—one Rabbi Ackerman from Borough Park, called “Mr. Redbeard” by Robbins—who specialized in the fashen-tantz,dancing with a bottle balanced on his head. Just before Fiddler’s Broadway opening, Robbins added a group bottle dance to the wedding scene that closes act one—a musical, choreographic, and emotional highlight of any production. Shortly after the bottle dance, Russians soldiers arrive and subject Anatevka to its first pogrom. The first items destroyed are wedding presents. From here to its close, Fiddler is remarkably serious for a musical.

Solomon’s part two gives ample space to the show’s visual aspects (sets, lights, costumes) and to Robbins as the controlling, universally hated, creator of the whole. But as set designer Boris Aronson reportedly said, in response to Robbins’ staging of the wedding, “Any man who can do that, I forgive anything.” Solomon casts producer Hal Prince as the production’s “good cop.” And while cut numbers are described, no excised lyrics or lines of dialogue are reprinted. For a close analysis of Fiddler’s text and music, look to Philip Lambert’s recent book To Broadway, To Life: The Musical Theater of Bock and Harnick (Oxford University Press, 2011). Lambert’s precise discussion of the sources for Fiddler’s Jewish content supplements Solomon’s more general consideration of the same issue. For example, Lambert quotes lyricist Sheldon Harnick’s source material for Fiddler’s opening number, “Prologue-Tradition,” in the book Life is with People, which Solomon notes was a primary source for the production. And Lambert listens closely to the phonograph records composer Jerry Bock had in his ear while composing the score. His clear discussion of musical details allows the musically-literate reader hear the “Jewish” aspects of Fiddler’s score with great specificity.

Throughout part two, Solomon ties creative decisions to the mid-1960s moment in American Jewish identity. She links Tevye’s final softening towards Chava, his daughter who marries outside the faith, to contemporary discussions about exogamous marriage and reads Golde’s scolding line, “Behave yourself! We’re not in America yet,” against the grain. In fact, Solomon notes, “figuratively, they have already made the journey, bearing the values of American tolerance and adaptability.”

Part three follows Fiddler on select journeys beyond Broadway to Israel, Brooklyn, Hollywood, and Poland—all fraught places in the history of the Jews. Fiddler’s first foreign productions were in Israel, and Solomon connects reception of the show to Israel’s victory in the Six Day War. She also charts the show’s translation into Hebrew and, eventually, Yiddish, which returned Tevye to the language of Sholem-Aleichem. In a welcome, still unusual move for musical theatre scholarship, Solomon next considers an amateur production—a 1968 middle school staging in Brooklyn that coincided with a well-studied shift in black-Jewish relations. The story of this production was first told by its director Richard Piro in his 1971 book Black Fiddler. Solomon, a professor of journalism, revives and enriches the tale, interviewing Piro and performers who appeared in the show.While at times the Brooklyn chapter strays from the specifics of Fiddler,the story is worth recounting for the way it presents the stakes involved in productions of Broadway musicals which, like Fiddler, raise political and social issues that cut to the heart of the American experiment. A middle school Guys and Dolls, she rightly notes, wouldn’t have had the same impact.

The final two chapters consider Fiddler in Hollywood—the making of the 1971 film—and in Poland—where the show has enjoyed an especially robust and varied performance history. Both chapters highlight how Fiddler became a vehicle for literally returning the destroyed culture of the shtetl to Eastern Europe. For the film, shot in Yugoslavia, a synagogue was built and decorated in late 19th century style, complete with elaborate interior murals. (Jewish religious practice receives careful attention in the film that is lacking in stage versions.) After shooting was done, director Norman Jewison wanted to preserve the synagogue set as an example of the demolished world of the shtetls, but a plan to move the “new old” structure to a university campus in Tel Aviv failed. Due to Cold War limitations on the transfer of payments across the iron curtain, royalties for the initial Polish productions went towards the renovation of Jewish cemeteries in Poland: Robbins wished they might benefit “living Jews.” As a frame for the Poland chapter, Solomon movingly recreates an experimental Fiddler staged in the streets of a village purged of its Jewish citizens over a half century earlier. As a whole, the stories in part three beautifully demonstrate “how a work of popular culture can glow with a radiant afterlife, illuminating for different audiences the pressing issues of their times.”

An Israeli producer searching for shows to take back to audiences in his home country declares he likes Fiddler in spite of himself, confessing “Schmaltz? Maybe. But so beautiful!” One member of a tougher crowd—Israeli intellectuals and critics—disagrees, dismissing Fiddler as “not even fresh schmaltz, [but] putrid schmaltz.”

A prominent thread running throughout parts two and three of Wonder of Wonders draws attention to how a range of Jewish individuals used (and use) Fiddler to work out issues of identity. For example, an Israeli producer searching for shows to take back to audiences in his home country declares he likes Fiddler in spite of himself, confessing “Schmaltz? Maybe. But so beautiful!” One member of a tougher crowd—Israeli intellectuals and critics—disagrees, dismissing Fiddler as “not even fresh schmaltz, [but] putrid schmaltz.” And Solomon describes director Jerome Robbins as “[laboring] mightily to burn away the schmaltz that for two decades had encased the world of the shtetl like amber.” These repeated invocations of schmaltz raise the issue of Fiddler and sentimentality. (Yiddish for rendered fat, schmaltz is used colloquially to refer—positively or, more often, negatively—to excessive, florid sentimentality.) Solomon generally reads Fiddler as lean and hard, emphasizing, for example, how Robbins’ choreography for the men at the wedding sought to bring a kind of “virile ferocity”—Robbins’ own description of the dancing he observed at Hasidic weddings—to the performance of Jewish masculinity. In this muscular, “burned away” reading of Fiddler, the well-known unruliness of Zero Mostel, the original Tevye, receives little emphasis. For Solomon, this is Robbins’ show and Mostel’s Borscht Belt ad libbing at many performances during the original Broadway run becomes a side note in the show’s history rather than another element of the show’s Jewishness. (Lambert’s chapter on Fiddler offers a section on Mostel and issues of Jewish content. On a similar theme, Lambert charts the strictly limited, carefully defined, Yiddish words appearing in the Broadway text.)

The utility with which Jews of many kinds could embrace Fiddler is captured in Solomon’s tightly focused description of the show’s “primary contradictory gesture”: “by turning toyre (Torah)—Jewish law and religious practice—into ‘tradition,’ it handed over a legacy that could be fondly claimed without exacting any demands.” Later, she locates Fiddler within a “Jewish identification that makes only sentimental demands.” In the end, Solomon withholds judgment on Fiddler’s impact on Jewish identity and generally celebrates the show’s ability to let secular Jews take a show tune like “Tradition” in the place of Torah. Her short discussion of Fiddler tchotchkes proves a highlight along this theme. Solomon even includes a photo of a “Tevye chip and dip set,” complete with carrot sticks and olives. Such details add texture to her presentation of Fiddler as “ethnic assertion” for non-religious Jews and “a screen onto which [American Jews] project their desire for a useable past.”

Taking the bottle dance full circle, in the epilogue Solomon profiles the Amazing Bottle Dancers, a professional dance troupe in Los Angeles that performs at Jewish weddings, keeping Rabbi Ackerman’s flashen-tantz alive by way of Jerome Robbins’ show-stopping Broadway re-making, in this case danced without fear a pogrom will spoil the party. As Solomon notes, Jewish American audiences “can supply the happy ending that [Fiddler] itself does not explicitly propose,” knowing that a remnant of the children and grandchildren of Tevye and Golde will survive to found the state of Israel and to remake the shtetl on Broadway in the guise of the indestructible, “fake” Anatevka.