“Only one thing is impossible for God: To find any sense in any copyright law on the planet.”

—Mark Twain

“It would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations, outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits.”

—Justice Oliver Wendel Holmes, Jr., Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co., 188 U.S. 239, 251 (1903)

Appropriation Art.

The Tate Museum defines it as “the practice of artists using pre-existing objects or images in their art with little transformation of the original.”1 Big names in this genre include Richard Prince, Jeff Koons, Roy Lichtenstein, and the grandmaster of appropriation, Andy Warhol. These artists deliberately—indeed, blatantly—copy pre-existing art into their works while making few, or sometimes no, alterations to the original work. No surprise that the list of synonyms for “appropriation” in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary includes “piracy,” “looting,” “misuse,” and—of course—“infringement.”

Works of appropriation art fit snugly within the Copyright Act’s definition of a “derivative work,” which it defines as “a work based upon one or more preexisting works.” (17 U.S.C. § 101.) And guess who owns the exclusive right to make, or license others to make, a “derivative work”? The owner of the copyright in that original work.

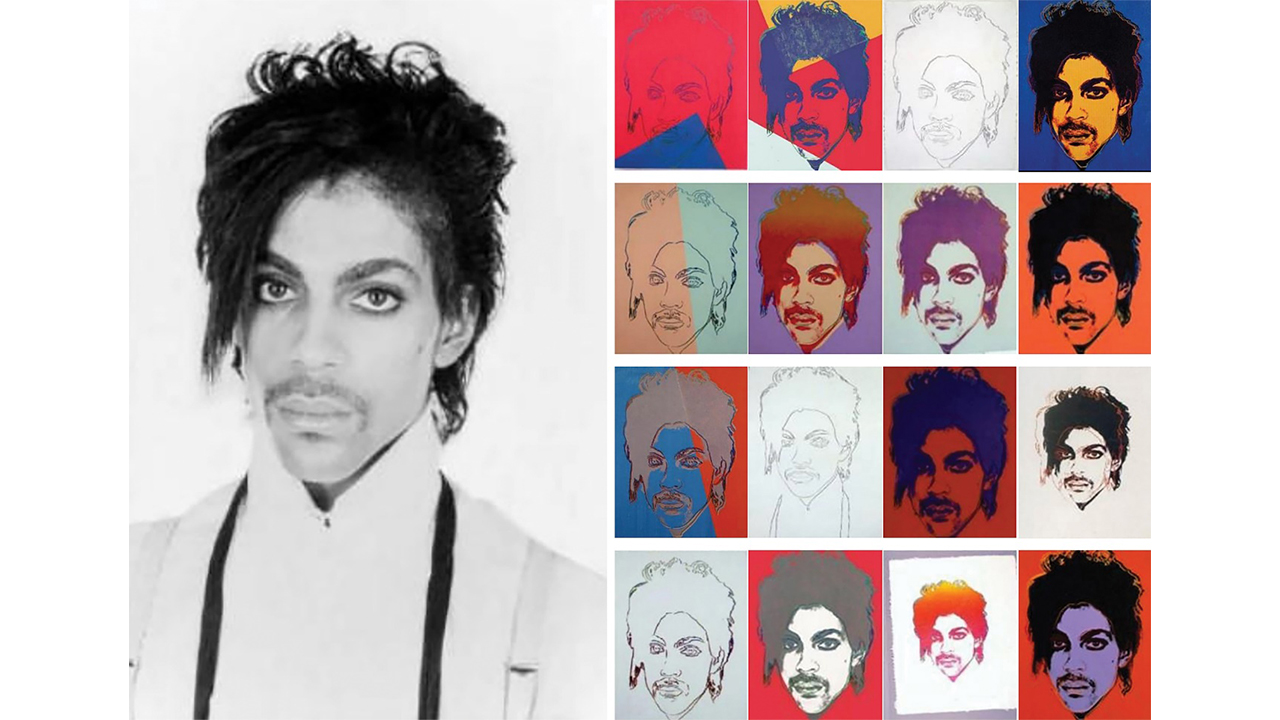

As such, appropriation art has not only outraged artists over the unauthorized and lucrative exploitation of their artwork but has been the subject of high-stakes lawsuits for decades. Appropriation artists defiantly operate under the flag of “fair use,” which some have described as a copyright lawyer’s full-employment act. Nevertheless, we copyright lawyers eagerly awaited the United States Supreme Court’s decision earlier this year in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, __ U.S. __ (May 18, 2023). This was the copyright infringement lawsuit pitting the professional photographer Lynn Goldsmith against the Andy Warhol Foundation over one of the works in Warhol’s Prince Series, which consists of sixteen silkscreen portraits and drawings, all based on Goldsmith’s copyrighted photograph of the musician Prince.

In the high court, the focus was whether the Warhol Foundation violated Goldsmith’s copyright when it licensed one of those Warhol works, Orange Prince (second row, far right of the Prince Series above), to Condé Nast for use on the cover of Vanity Fair magazine. Warhol had created the work without Goldsmith’s knowledge or consent, and she received none of the $10,000 licensing fee paid to the Warhol Foundation for use of the image.

First, a little background.

Much has changed in the realm of copyright law since 1787, when the drafters of our Constitution formally recognized the importance of promoting all types of creativity by adding to Article I the Patent and Copyright Clause, which grants Congress the power “[t]o promote the progress of science and useful arts” by “securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive rights to their respective writings and discoveries.” (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8).

That clause reflects a pragmatic economic view of science and the arts, namely, as the Supreme Court explained in Mazer v. Stein, 347 U.S. 201, 219 (1954), the drafters’ “conviction that encouragement of individual effort by personal gain is the best way to advance public welfare through the talents of authors and inventors.”

But that clause includes another condition, namely, that the monopoly granted to artists over their creations shall be for only “a limited time.” Why limited? So that when those monopolies expire, the artists’ creations enter the public domain, free for all future authors and artists to build on by reimaging those works and using them as inspirations for valuable new creations.

The deeper truth, of course, is that prior art influences and inspires every subsequent artist—painter, author, playwright—regardless of whether we label the result of that influence an “appropriation.”

The wisdom embedded in that Constitutional clause—namely, the importance of a limited-time monopoly—has bequeathed upon our nation a cultural fortune inspired by works in the public domain—creations, performances, derivative works, and reproductions that could not happen if the original works were still protected by copyright. Take, for example, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Her novel has inspired several motion picture and TV versions and a variety of other derivatives, including the novel Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, none of which would be possible without the public domain. The plays of William Shakespeare are performed throughout the nation and the world in a wide variety of venues—from public schools to for-profit theaters—all for free, unlike the steep license fees required to stage, say, A Chorus Line or Hamilton. So, too, the public domain status of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein has given us everything from horror movies (such as the 1931 Frankenstein starring Boris Karloff) to the Mel Brooks comic classic, Young Frankenstein (1974).

The deeper truth, of course, is that prior art influences and inspires every subsequent artist—painter, author, playwright—regardless of whether we label the result of that influence an “appropriation.” Judicial recognition of this influence—of how new art arises from existing art—dates back in this country to at least the 1845 opinion of Justice Joseph Story in Emerson v. Davies, 8 F.Cas. 615, 619, where he wrote: “[I]n literature, in science and in art, there are, and can be, few, if any, things, which … are strictly new and original throughout. Every book in literature, science, and art, borrows, and must necessarily borrow, and use much which was well known and used before.” Of course, the wisdom in Justice Story’s observation can be traced all the way back to the Book of Ecclesiastes, which tells us: “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”

Sometimes that borrowing and inspiration is obvious, such as Tom Stoppard’s play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, which borrows from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Sometimes that influence is more obscure, such as Shakespeare’s Hamlet, which stems from the remarkably similar thirteenth-century Scandinavian revenge tale called Amleth.2 And no doubt Amleth has its own antecedents. Indeed, a recent massive data study confirms that there are only six basic story plots in all of literature.3 Similarly, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston currently has an exhibit showing the profound influence that the woodblock prints and paintings by Katsushika Housai, a Japanese artist of the early nineteenth century, had on an array of more modern artists from Claude Monet to Roy Lichtenstein.4

But none of the above examples—all “derivative works” or “public performances” under copyright law—would have been possible without the freedom of the public domain.

Ah, but going back to its origins—back to 1790 when Congress enacted the first Copyright Act—the “limited time” of that monopoly was just fourteen years, after which the work would be free to all. However, at various times over the past two centuries that “limited time” has grown, slowly at first—from fourteen to twenty-eight years in 1831—and exponentially in the latter half of the twentieth century. The most recent extension, the result of intense lobbying by major corporations in the entertainment industry, was the 1998 Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (derisively nicknamed the Mickey Mouse Act, since it was enacted just before the copyright in Mickey Mouse would have expired). That Act added another twenty years to the copyright monopoly for most works, which now lasts ninety-five years from publication (or seventy years after the death of the author).

Thus every original work of authorship created fewer than ninety-five years ago is still protected by copyright. That means, for example, the exclusive rights of copyright will continue to shield Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) until 2042 and J.K. Rowling’s first Harry Potter novel (1997) until 2092, and her subsequent Harry Potter novels into the twenty-second century. Ironically, the musical Rent (1996)—itself a derivative work based on Puccini’s La Bohème (1896), which was based on an 1851 novel, both of which are now in the public domain—will remain protected by copyright until 2091.

Accordingly, the focus has shifted to the “fair use” doctrine. Namely, under what circumstances can you make an unauthorized use of a copyrighted work that would otherwise be deemed an infringement?

So how does “fair use” work—or, at least, how is it supposed to work? Section 107 of the Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. § 107, provides the statutory framework and identifies certain types of uses—such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research—as examples that may qualify. The key word is “may.” In evaluating the question of fair use, Section 107 requires the court to consider four factors, the most important of which has become the first one: “the purpose and character of the use, including whether that use is of commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.”5

Over the past few decades, that first factor has been the focus of many important “fair use” cases. Specifically, courts ask whether the “purpose and character” of the use is “transformative.” That is, whether it adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the original with new expression, meaning, or message—or whether it merely copies from the original.

The wisdom in Justice Story’s observation can be traced all the way back to the Book of Ecclesiastes, which tells us: “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”

This “transformative use” question was at the heart of the Supreme Court’s first major “fair use” decision, which involved, believe it or not, the song “Pretty Woman,” which is 2 Live Crew’s raunchy parody of the Roy Orbison classic country rock song “Oh, Pretty Woman.” Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, 510 U.S. 569 (1994).6

When you listen to the 2 Live Crew version, what is striking is how much of the copyrighted music from the original is copied. But as the Court explained, that is what a parody requires, since the listener has to recognize what is being parodied:7

For the purposes of copyright law, … the heart of any parodist’s claim to quote from existing material is the use of some elements of a prior author’s composition to create a new one that, at least in part, comments on that author’s works.

Writing for the unanimous Supreme Court, Justice David Souter stated “that a work’s commercial nature is only one element” by which to judge fair use. Souter noted the court “might not assign a high rank” to the 2 Live Crew song, but it is a legitimate parody that “can be taken as a comment on the naiveté of the original of an earlier day, as a rejection of its sentiment that ignores the ugliness of street life and the debasement that it signifies.”

In order to illustrate this, the opinion includes the lyrics to both songs. Below is a side-by-side comparison of the second stanzas of each:

| Roy Orbison Original | 2 Live Crew’s Version |

|

Pretty Woman, won’t you pardon me,

Pretty Woman, I couldn’t help but see,

Pretty Woman, that you look lovely as can be,

Are you lonely just like me?

Pretty woman |

Big hairy woman, you need to shave that stuff,

Big hairy woman, you know I bet it’s tough,

Big hairy woman, all that hair it ain’t legit,

Cause you look like “Cousin Itt,”

Big hairy woman |

While that opinion cleared some of the debris from the “fair use” highway for parodies,8 it offered little guidance in the realm of appropriation art. Namely, what constitutes a “transformative use” of someone else’s visual creation.

In subsequent years, Richard Prince has occupied a starring role as defendant in some high-profile copyright infringement cases in which his attorneys argued, sometimes successfully and sometimes not, that his appropriation “commented” upon the original and was thus “transformative.”

See what you think.

In 2009 the French photographer Patrick Cariou sued Richard Prince over Prince’s 2008 “Canal Zone” series of paintings, which incorporated several photographs from Cariou’s 2000 book, Yes, Rasta. Prince had copied several of Cariou’s photographs—indeed, cut the photos out of the book—added something new and sold his versions at sums vastly greater than Cariou had earned from the publication of his book. Among the works at issue is Richard Prince’s additions to one such original photograph shown on the right below:

Original photograph from French photographer Patrick Cariou from his 2000 book, Yes, Rasta (left) and Richard Prince’s “appropriation” in his 2008 “Canal Zone” series of paintings.

While that case was eventually settled—after extensive litigation in the trial and appellate courts—Richard Prince was also the defendant in even more extreme works of appropriation art, which he sold—like the Cariou appropriations—at eye-popping numbers. One example is the pending lawsuit brought by the photographer Donald Graham. At issue in that case is Richard Prince’s Portrait of Rastajay92, which appropriates Graham’s 1998 photograph Rastafarian Smoking a Joint. Prince copied an Instagram user’s post sharing Graham’s photo of the shirtless Jamaican man that the user had captioned “Real Bongo Nyah man a real Congo Nyah.” In his version, blown up to a 4 ft, x 5 ft. inkjet print, all that Richard Prince added was the comment “Canal Zinian da lam jam.” Shown below is Graham’s original photograph and Prince’s appropriation for his “New Portraits” series:

Donald Graham’s 1998 photograph Rastafarian Smoking a Joint (left) and Richard Prince’s “appropriation” Portrait of Rastajay92.

And then there is Richard Prince’s Portrait of Kim Gordon, which appropriates Eric McNatt’s photograph of Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, which had been commissioned for Paper Magazine in 2014.

Eric McNatt’s photograph of Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon (left) and Richard Prince’s Portrait of Kim Gordon.

Richard Prince’s lawyers argued that his version qualified as a “transformative” fair use in that by adding the Instagram frame and comments, as well as the “intentional cropping of images in an homage to Andy Warhol” and “absurdly proportioned scale and Alice in Wonderland-dreamlike quality” transform the context of the images and result in “dramatically different conclusions drawn by the viewer.”

Both of those lawsuits were still pending when the Supreme Court announced its decision in Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith.

The facts of that case are as follows: Lynn Goldsmith is, in the words of Justice Sonya Sotomayer, “a trailblazer” who “began a career in rock-and-roll photography when there were few women in the genre. Her award-winning concert and portrait images, however, shot to the top. Goldsmith’s work appeared in Life, Time, Rolling Stone, and People magazines, not to mention the National Portrait Gallery and the Museum of Modern Art. She captured some of the twentieth century’s greatest rock stars: Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger, Patti Smith, Bruce Springsteen, and, as relevant here, Prince.”

Back in 1981, Newsweek commissioned Goldsmith to photograph a then “up and coming” musician named Prince Rogers Nelson, after which Newsweek published one of Goldsmith’s photos along with an article about Prince. Years later, Goldsmith granted a limited license to Vanity Fair for use of one of her Prince photos as an “artist reference for an illustration.” The terms of the license specified that the use would be for “one time” only. Vanity Fair hired Warhol to create the illustration, and Warhol used Goldsmith’s photo to create a purple silkscreen portrait of Prince, which appeared with an article about Prince in Vanity Fair’s November 1984 issue (shown below).

Vanity Fair’s November 1984 issue, featuring Andy Warhol’s purple silkscreen of Goldsmith’s photograph.

The magazine credited Goldsmith for the “source photograph” and paid her $400.

After Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent company (Condé Nast) purchased a $10,000 license from the Foundation to publish Orange Prince, one of the sixteen Warhol works based on Goldsmith’s photograph. She did not know about the Prince Series until 2016, when she saw Orange Prince on the cover of Vanity Fair.

Andy Warhol’s Orange Prince silkscreen (left) and Goldsmith’s original photograph.

Goldsmith notified the Warhol Foundation that it had infringed her photograph, the Foundation sued her for declaratory judgment of fair use, and Goldsmith countersued for infringement. The trial judge found the Orange Prince to be a transformative “fair use” of Goldsmith’s photograph, i.e., no infringement. The court of appeals reversed, rejecting the “fair use” argument. And thus the issue before the Supreme Court: does the Orange Prince silkscreen constitute a protected fair use of the original photograph or an unfair expropriation of someone else’s creativity for commercial gain?

During the months leading up to that decision, there was much speculation. Would the result be the typical 6-3 division between the conservative and liberal members of the Court? And if so, which side would the conservatives take? Add to that thirty-eight amicus briefs filed by a wide range of non-parties—eight supporting the Warhol Foundation, twenty supporting Goldsmith, and nine in support of neither party.

Souter noted the court “might not assign a high rank” to the 2 Live Crew song, but it is a legitimate parody that “can be taken as a comment on the naiveté of the original of an earlier day, as a rejection of its sentiment that ignores the ugliness of street life and the debasement that it signifies.”

One of those amicus briefs was filed by the Author’s Guild, an organization in which I am a member. The Guild stressed the importance, in analyzing transformative use, of protecting the original author’s derivative works right, describing it as a “critical incentive for the production and dissemination” of written works and explaining how essential the derivative work markets (such as audiobooks, translations, eBooks, etc.) are for an author’s earnings. Citing author earnings surveys, the brief continued: “Without the potential to exploit the derivative-work rights in their books . . . authors would earn far less money, and many would have to stop writing professionally. Ultimately, readers would lose out.”

The most intriguing of those amicus briefs was one filed by an entity that rarely enters the copyright fray: the U.S. government. And in retrospect, the government’s amicus brief may have been the most important one because it reframed and narrowed what it contended was the real question before the Court.

The Warhol Foundation had framed that question as “whether a work of art is ‘transformative’ when it conveys a different meaning or message from its source material.” It argued that the paintings were “transformative works,” not copyright infringement, because “Warhol added layers of bright and unnatural colors, conspicuous hand-drawn outlines and line screens, and stark black shading that exaggerated Prince’s features. The result in all the Prince Series works is a flat, impersonal, disembodied, mask-like appearance.” (Brief For Petitioner at 19 [June 10, 2022].) But the government argued that the question presented should be far narrower, namely, “whether petitioner established that its licensing of the silkscreen image [to a magazine] was a ‘transformative’ use.” (emphasis added)

And that narrower focus became the key axis on which a deeply divided Supreme Court ruled. The result? The money and copyright won by a 7-2 majority, and Warhol and his Foundation’s claim of fair use lost.

As for that seven Justice majority? Contrary to the usual conservatives-versus-liberals divide that we have come to expect from this Court, Justice Sonya Sotomayer wrote the majority opinion, and she was joined by a motley crew that included Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Katanji Jackson, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Barrett. A furious Justice Elena Kagan wrote the fiery dissenting opinion in which Chief Justice John Roberts joined.

Her [Justice Kagan’s] dissent takes us on a fascinating journey through the worlds of literature, art, and music—and describes in detail how great works in each of those fields are based upon prior works. In the process, she issues a somewhat over-the-top warning about what the majority’s decision might allow.

Justice Sotomayer’s majority opinion is most striking in the tightness of its focus. She decided the fair use question only as to the licensing of the work to the magazine—and not as to Warhol’s creation of the Prince Series itself. As she explains, even though Warhol’s Orange Prince undoubtedly added new expression to Goldsmith’s original photograph, it was not a fair use because both Warhol and Goldsmith were engaged in the commercial enterprise of licensing images of Prince to magazines. “Such licenses, for photographs or derivatives of them, are how photographers like Goldsmith make a living. They provide an economic incentive to create original works, which is the goal of copyright.” Slip Op., at 22. “To hold otherwise would potentially authorize a range of commercial copying of photographs, to be used for purposes that are substantially the same as those of the originals. As long as the user somehow portrays the subject of the photograph differently, he could make modest alterations to the original, sell it to an outlet to accompany a story about the subject, and claim transformative use.” Id. at 33.

In his concurring opinion (in which Justice Jackson joined), Justice Gorsuch emphasized the narrowness of the holding, explaining what the case does not involve:

Last but hardly least, while our interpretation of the first fair-use factor does not favor the Foundation in this case, it may in others. If, for example, the Foundation had sought to display Mr. Warhol’s image of Prince in a nonprofit museum or a for-profit book commenting on 20th-century art, the purpose and character of that use might well point to fair use. But those cases are not this case. Before us, Ms. Goldsmith challenges only the Foundation’s effort to use its portrait as a commercial substitute for her own protected photograph in sales to magazines looking for images of Prince to accompany articles about the musician. And our only point today is that, while the Foundation may often have a fair-use defense for Mr. Warhol’s work, that does not mean it always will.

In her angry dissent, Justice Kagan, joined by Chief Justice Roberts, wrote that the decision “will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature,” she wrote, “It will make our world poorer.”

As Congress knew, and as this Court once saw, new creations come from building on—and, in the process, transforming—those coming before. Today’s decision stymies and suppresses that process, in art and every other kind of creative endeavor. The decision enhances a copyright holder’s power to inhibit artistic development by enabling her to block even the use of a work to fashion something quite different. Or viewed the other way round, the decision impedes non-copyright holders’ artistic pursuits by preventing them from making even the most novel uses of existing materials. On either account, the public loses: The decision operates to constrain creative expression.

Her dissent takes us on a fascinating journey through the worlds of literature, art, and music—and describes in detail how great works in each of those fields are based upon prior works. In the process, she issues a somewhat over-the-top warning about what the majority’s decision might allow. Here, for example, is part of her screed on music, an art form that she describes as “positively rife with copying of all kinds.” She continues:

Suppose some early blues artist (W. C. Handy, perhaps?) had copyrighted the 12-bar, three-chord form—the essential foundation (much as Goldsmith’s photo is to Warhol’s silkscreen) of many blues songs. Under the majority’s view, Handy could then have controlled—meaning, curtailed—the development of the genre. And also of a fair bit of rock and roll. “Just another rendition of 12-bar blues for sale in record stores,” the majority would say to Chuck Berry (Johnny B. Goode), Bill Haley (Rock Around the Clock), Jimi Hendrix (Red House), or Eric Clapton (Crossroads). Or to switch genres, imagine a pioneering classical composer (Haydn?) had copyrighted the three-section sonata form. “One more piece built on the same old structure, for use in concert halls,” the majority might say to Mozart and Beethoven and countless others: “Sure, some new notes, but the backbone of your compositions is identical.”

So where does that leave the rest of us?

Good question, the answer to which we copyright lawyers are trying to sort out. On the one hand, the majority opinion seems reassuringly narrow, namely, it is not a fair use when your admittedly creative, even transformative, derivative work is nevertheless used for the exact same commercial purpose as the original, i.e., licensed for profit to a magazine. But wait a minute. How is that different from the 2 Live Crew version of “Pretty Woman,” an undisputed transformative work that was nevertheless used for the exact same commercial purpose as the original, namely, licensed for profit to a record company?

It reminds me of an old Jewish joke: A curious gentile asks the wise old rabbi, “Rabbi, please explain why a Jew always answers a question with question?” The rabbi ponders the matter as he strokes his beard and finally responds, “And tell me, young man, why shouldn’t a Jew answer a question with a question?”

Well, we copyright lawyers are still trying to answer that question as well, as are federal trial and appellate courts around the nation looking for guidance to the Supreme Court’s decision in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith. Stay tuned.

And at least for now, rabbi, why shouldn’t a copyright lawyer answer a fair use question with another question?