At some point, every child fantasizes about running away from home. Elsewhere, the child thinks, parents would not treat children so unfairly. Life wouldn’t be governed by so many stringent rules. In other homes, in other places, surely adults wouldn’t be so keen on sending you to your room.

In Loretta Mason Potts, this “elsewhere” isn’t a distant fantasy, but a very real place that exists at the end of a tunnel in the back of a closet. Here, a beautiful countess lives in a castle with a doting general, and lavish parties are thrown on a seemingly daily basis. Cakes and hamburgers are eaten without concern for health, there’s a snow machine in case the Countess suddenly desires a sleigh ride, and rudeness isn’t just tolerated, but actively encouraged. In short, it is in many ways a child’s dream.

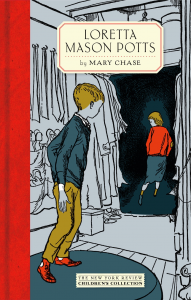

The tension between this magical land and reality is what largely drives this novel, originally published in 1958 and reissued last summer (2014) by the New York Review Children’s Collection. It was one of only two children’s books by Mary Chase, a playwright best known for Harvey, which won the 1945 Pulitzer Prize for Drama and was made into a film in 1950 starring James Stewart.

The book begins with a bang: 10-year-old Colin Mason discovers he has an unknown, older sister named Loretta. Soon after this disclosure, Loretta returns to live with the Mason family after having spent the past seven years with Mr. and Mrs. Potts, farmers who live nearby. She is considered a “bad girl,” and Colin and his three younger siblings are wary of this crude interloper. Manipulative, quick to lie, and a master of backtalk, Loretta comes as a shock to the well-behaved Mason brood.

Although the discovery of a long-lost sister and her subsequent return home would be basis enough for a book, the emotional and logistical implications of these circumstances are largely glossed over. This is not Judy Blume, but a fantasy story, and the impact of events are a very distant second to the events themselves. Even Mr. and Mrs. Mason’s divorce, which must have been unnerving for some readers at the time to find mention of in a children’s book, is relegated to one-line.

Without the encumbrance of untangling feelings, the plot quickly moves forward to the main adventure, which begins when Colin learns of Loretta’s secret excursions to the Countess’s magical land. As it turns out, Loretta discovered entry to this other world while visiting the Potts farm when she was five. In this land, accessed through a tunnel on a hill, she is adored, and lauded for being “refreshing” and “utterly, utterly amusing,” particularly when she makes coarse or insulting remarks. The Countess eagerly awaits her visits, and has her hold audience with all manner of regal well-wishers. Since her discovery, Loretta has insisted on living with Mr. and Mrs. Potts, kicking and screaming whenever threatened with returning home. Despite weekly visits—and pleadings—from her mother, the couple becomes de facto foster parents, and Loretta maintains proximity to her private wonderland. Encouraged by the Countess, Loretta’s behavior worsens. Finally, she grows so abhorrent that the couple sends her packing back to her rightful family.

The novel exhibits the contradictions of its era, when the golden ideals of nuclear family life clashed with rampant fear of juvenile delinquency. For young readers, the boldness with which the Mason children disregard social conventions will no doubt seem just as deliciously fascinating as it does despicable.

Colin begins to unravel this story one night when he secretly follows Loretta through a tunnel, which has newly appeared in Loretta’s closet at the Mason home (the Countess’s team, it turns out, digs quickly). Upon seeing the lush forest and stately castle, Colin is immediately entranced, much like Loretta was so many years ago. In time, each of the Mason children end up journeying to this other realm, and are delighted to find themselves treated as guests of honor. They are flattered and spoiled, and quickly supplant a shocked Loretta as the favored children—a fickleness that stands in stark contrast to Mrs. Mason’s campaign to bring Loretta home. Soon, the entire Mason clan is displaying the same sort of rude, boorish behavior as their eldest sister. The Countess calls this sort of conduct “interesting” and “charming,” and winning her approval becomes the highest priority; who would want to be considered dull by a beautiful creature like the Countess?

Trouble begins when the children start to exhibit this uncouth behavior at home. They tell their mother how very dull she is. The same sly look begins to appear in all their eyes. Even Colin, normally a straight-A student, is caught by police officers hanging out in a Jaguar convertible parked on the street (the Countess had told Colin that a red convertible was much more his style than the bicycle he normally rode).

Although this sort of disobedience might be typical of an adolescent, it seems startling in younger children, who are expected to remain snugly under their parents’ thumbs. The novel exhibits the contradictions of its era, when the golden ideals of nuclear family life clashed with rampant fear of juvenile delinquency. For young readers, the boldness with which the Mason children disregard social conventions will no doubt seem just as deliciously fascinating as it does despicable. On the one hand, we all itch to steal our siblings’ toys and tell our parents to get lost once in a while. On the other hand, most of us do not actively wish to become playground pariahs.

Eventually, it becomes clear to Mrs. Mason that she is losing control of her brood, just as she once lost control of Loretta. Determined not to let her offspring slip from her grip, she herself visits the Countess’s castle in attempt to find out the cause of the evil that has gripped her family. It is an act that defies the rules of children’s literature, which generally prohibit adults from entering the secret lands that children visit. Among the exceptions is L. Frank Baum’s 1910 novel, The Emerald City of Oz, the sixth and, for a time, the last in the original Oz, where Dorothy’s Uncle Henry and Aunt Em go to Oz to live.

Typically, these rules also dictate that children resolve conflicts on their own—proof to young readers that they, like these juvenile heroes, are more resourceful than adults give them credit for. But in Loretta Mason Potts, it is Mrs. Mason who more or less saves the day. She is the only one who sees the Countess’s cold, cunning heart for what it is, and the only one willing to take a stand against the beautiful aristocrat. Although much of contemporary children’s literature is geared toward empowering kids, this book is more of a reminder that mother does indeed know best. It seems that we become rather unsavory, unlikable creatures when her influence is superseded or her guidance ignored. And so, the natural order of parent over child is not only upheld, but affirmed.

In the end, the book is a somewhat softened rendition of the archetypal good versus evil—rude versus well-behaved is perhaps a more apt description. Of course, the struggle between impulse and common sense, our own wicked inclinations and necessary politesse is just as relevant today as it was in 1958. It is a simple condition of human nature, one that will continue to resonate in every decade, and at every age (As adults, however, mistreating siblings is generally the stuff of dysfunctional family dramas rather than fantasy fiction). Will kids extrapolate behavioral lessons from the book? Maybe. But more likely they’ll just have a good romp through a land where ice-cream and snowfalls wait at their beck and call.