Eliot’s Greatest Poem and His antisemitism

On Matthew Hollis’s The Waste Land: A Biography of a Poem

March 26, 2024

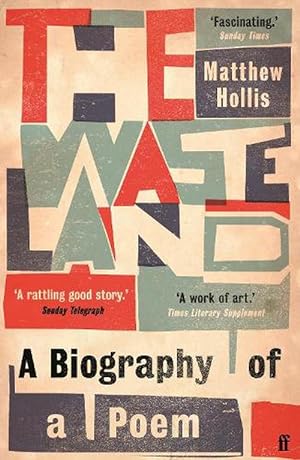

The Waste Land: A Biography of a Poem

My first impression, upon opening Hollis’s The Waste Land: A Biography of a Poem was admittedly delicious. A usual kind of epigraph greets us: “There is always another one walking beside you,” from Eliot’s poem, but then we turn the page, and on the back of the epigraph page is a quotation from Eliot, a meaty paragraph, and facing it, on the right-hand side, is a shorter passage from Pound. Right away, then, the two men are side by side, in the opening pages in a way that disrupts the usual front page material of a tome. It is a nice touch that not only forecasts the book’s focus on the relationship between the two men in the crafting of one of the inarguably influential English language poems of the twentieth century but also indicates the attention to detail and summoning of atmosphere that characterize the bulk of Hollis’s project, if not its achievement. Which is this: to demythologize, and at times painfully, re-animate the gross disturbances in Eliot’s life and character that, for better or worse, have bequeathed us the still-jarring title poem.

Hollis gives us descriptions that sharpen some of what is known by those who already know loosely of Eliot’s world. Yes, we know he worked in a bank, but Hollis tells us he “worked in the Colonial and Foreign Department,” a detail that instantly resonates with the imperial and multilinguistic qualities of “The Waste Land” poem itself, to say nothing of the subterranean qualities of the poem that come to seem resonant with Eliot working “in a sub-sub basement, in a row of co-workers.” (13) Hollis tells us that Aldous Huxley, after a visit, remarked upon this subterranean location, saying also that Eliot seemed “the most bank-clerky of all bank clerks.” (13) And yes, we know his marriage to Vivien Eliot was difficult, but Hollis reveals Eliot’s view that the marriage to the woman, who like Eliot had mental health struggles, was “the most awful nightmare of anxiety that the mind of man could conceive.” (14) Even without Hollis making explicit connections to the poem that is the subject of the book, we start to understand implicitly how the scale and scope of the poem came to be in the first twenty pages of the book. The pacing is excellent.

We certainly encounter a more dimensional and occasionally heartbroken Eliot in these pages. Hollis writes of how Eliot learned of his father’s passing: Eliot was unable to respond to his mother’s telegram for four days, and when he did, it was minimal, only able to summon up a restatement of his love for her and a longing “for her to sing him the songs he knew in childhood.” (15) The subsequent “silence” then “descended between mother and son” that “would fall to Vivien to break”; “a further week would pass before Eliot would commit his own feelings to paper. Little, very little, of what one feels can ever filter through to pen and ink, he wrote.” By the end of the paragraph, Hollis has recreated the struggle of Eliot corresponding with his brother and mother, only to return to his home state of Missouri ten years later, “and by that time his mother, too, was dead.” (15) The helicopter view that biographical research provides proves poignant in stretches like these, where problems of Eliot’s, such as his anti-semitism, recede (more on this below): “Fourteen years would pass before Eliot visited his father’s grave. It was then that he confessed, ‘I shall be haunted by my last sight of him until my last day.’” (16) More than just helping us to appreciate the relationship between art and life, or the human-ness of Eliot himself, Hollis seems to aim at restoring the balance between reading and remembering.

Even without Hollis making explicit connections to the poem that is the subject of the book, we start to understand implicitly how the scale and scope of the poem came to be in the first twenty pages of the book. The pacing is excellent.

Hollis has indeed taken great pains to reconstruct the day-by-day, virtually line-by-line drafting, erasing, and reconsidering that Eliot undertook with the poem. It is a safe bet that if someone is going to be interested enough in reading an entire book about a single poem, they will be primed to be enlivened by such attention to detail. A passage will give you a sense of Hollis’s detective work:

Eliot’s month in Margate didn’t produce only rough drafts for the long poem. There were two single–and apparently discrete poems that he also drafted on that second fortnight in the town. For all the literary distance that he had travelled since the Hogarth Poems of 1919, it was in some way a surprise to find him return to something like the ‘French’ form of the late war years, but so he did, in both pieces. ‘Dirge,’ a song, was the flightier of the two poems, in two variable tetrametic stanzas, six lines by ten; ‘Elegy,’ the second, was the more formal, locked stiffly into abcb quatrains. There was a proximity to them that was more than metric: they were written on backpages of the same leaf, for which there should have been no need: new poems take new leaves, unless no leaves are to be had, which is perhaps the situation that Eliot found himself in that day in the Nayland Rock shelter. (302)

Hollis clearly relishes in tracking Eliot’s geographical movements as well as the movements of his hand, such that we might also start to fill in our own imaginative flourishes: the scooching back of his chair, the drawing of a dusty heavy curtain, the bleak quality of daylight in the room itself. Hollis’s omniscience almost becomes unstated and odd: “it was in some way a surprise” to whom but Hollis? We get, in passages like these, an exhilarating, breathtakingly close tour of how art is, or might be, made.

I especially was struck by not only Hollis’s dramatization of the composition process, with its own questions of how Eliot engaged tradition, but of his handling of Eliot’s anti-semitism–again, as part of tradition (on and off the page). Hollis’s writing shines when he shows the problem of the social as inextricable from questions of poiesis. At the same time, it is an open question, in my mind, whether spending this much time documenting the traces of anti-Semitism does not end up implicitly indulging in the larger public fascination with dead Jews that is a frequently unremarked-upon legacy of anti-semitism.

Hollis’s project is at least made tolerable by the frequency with which he returns to anti-Semitism as a problem, and it is clearly a question that he does not, ultimately, take for granted.

Consider this passage, after the one quoted above, where the question about how to write about anti-semitism becomes anything but settled. Hollis observes how

‘Dirge,’ was seemingly the first to be written. Once again Eliot had returned to the same song in the same scene of the same play, Ariel’s dirge in The Tempest: Full fathom five thy father lies. But here, in Eliot’s hand, it was given a horrific twist:

Full fathom five your Bleistein lies

Under the flatfish and the squids.

Graves’ Disease in a dead {man’s

jew’s eyes!

Where the crabs have nibb eat the lids.

Again he was reaching towards anti-Jewish tropes. A Jew’s-eye was proverbially an object of prized value, but for all the wrong reasons: it could be a medieval torture to extract monies from defaulting Jews.

Hollis continues in a long, meaty paragraph about the difference between “jew” and “Jew,” about Eliot’s choosing between “a dead jew (again the lower case) or a dead man (the universal case)”, and the alleged back and forth of Eliot further thinking through the implication of turning his dead father into a Jew: “Shakespeare’s word ‘father’ had become Eliot’s word ‘Bleistein’, and Eliot may very well have had in mind a symbol of the same, a projection of his father as the figure dead to him, as the ‘other,’ as the one outside of him–in Eliot’s Unitarian upbringing, everything represented by the ‘Jew.’”(303)

The level of detail here is such that I had to reread it several times, making sure I was sifting through the inferences accurately; Hollis’s solution is to perform a zoom-out. He tells us that “[s]uch an amalgam reading of the Jew-father wouldn’t lessen anti-semitic offence, but it might inform our understanding of his motivation.” (303) That we might still not want to spend our time “understanding” the “motivation” of the anti-Semitic Eliot is not beside the point either. At a certain point, it should be enough to know that he was, indisputably, anti-Semitic, although readers who feel uninformed about this aspect of history (literary and not) might desire or need this sort of explanation. Hollis grapples with this question of writing about anti-Semitism explicitly, and his solution also includes tipping his hand a little, repeating the dehumanizing language of Eliot in his attempt to dramatize what it must have been like to be in the mind of the anti-Semitic Eliot (in case it is not clear where I stand on this–I, as a Jew, don’t want to linger there, but I would have, once; I fell in love with Eliot’s work in my late adolescence and I remember standing in the aisle of a Borders bookstore, reading some of Eliot’s early verse and feeling both excited by the rhythm and tautness of the imagery as well as baffled by his use of Jews): “So which was it to be, a Jew or a man? It would take a month or two for Eliot to resolve, but when, in Lausanne that winter, he made a fair copy of the poem in the manuscript, he would choose which. Jew. Shamefully he picked Jew.” (303) Hollis’s project is at least made tolerable by the frequency with which he returns to anti-Semitism as a problem, and it is clearly a question that he does not, ultimately, take for granted.

Of the many ways that this book might resonate with an audience, one way is Hollis’s exploration of how to make art in a world where the cost of living is high, both emotionally, economically, and bodily. This implicit problem is established early on in the book when Hollis quotes Virginia Woolf’s note after meeting him one night at a dinner with the Woolfs: Eliot “produced 3 or 4 poems for us to look at–the fruit of two years, since he works all day in a Bank, & in his reasonable way thinks regular work good for people of nervous constitutions.” (8) Hollis later writes that this schedule, far from being one of good working conditions, contributed to Eliot’s “mind and body” being “exhausted” by this “combination.” (9)

Of the many ways that this book might resonate with an audience, one way is Hollis’s exploration of how to make art in a world where the cost of living is high, both emotionally, economically, and bodily.

It is the plethora of small moments of historical reconstruction like these that make the book of use to conversations happening today about the making of art in late capitalism, or of even just being a human at all, who aspires to live, well, unexhausted in body and mind. Hollis’s book is a useful contribution to the demythologizing of the conditions of poetic output but also to the demythologizing, if anyone still truly believes it, that the relatively recent past did not somehow also strain and sap people in systematic ways. Art is made by nervous, sweaty humans in innately unpoetic historical traps great and small; for Eliot, World War I, London, social unrest, what we would call mental health today, his marriage, and the sickness of imagination and heart that anti-Semitism must be understood to be. Hollis does not only document the history of the poem’s production and this moment in time–he allows himself, for better and for worse, to get swept up in the drama: “As the world began to rise from its knees in the autumn of 1918, Eliot had begun sinking to his. He worried that his mind no longer acted as once it did, and acceded to [his wife] Vivien’s insistence upon a period of what she called complete mental rest.” (9) Hollis by and large excels in mixing metaphorical and matter-of-fact prose, the way that Eliot’s poem is a “mixing” of “Memory and desire.”