Down The Mean Streets of St. Louis

An investigative journalist tells the affecting story of the Black boy’s life he could not save.

By Gerald Early

June 10, 2022

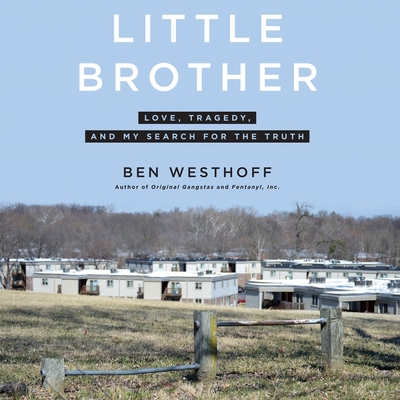

Little Brother: Love, Tragedy, and My Search for the Truth

Proper men and women

Some years ago, when I was in Detroit researching an article, I was commissioned to write about Motown Records. I interviewed, among others, Maxine Powell, owner of a charm school and etiquette instructor for young Motown stars like the Supremes, Stevie Wonder, the Marvelettes, et al. She was quite the personality, an extraordinary woman, gracious but tough, performative but with a gimlet eye.

“I taught them how to conduct themselves, how to walk, how to eat properly, so that they could be in the company of kings and queens,” she said. “They came from backgrounds where they had to be taught how to be proper young men and young women,” she continued. She was proud of her work, and of her product, transforming working-class Black kids who dreamed of being professional singers into people who could represent the race well, as it were, as public figures, who were no longer “uncouth,” to use her term.

As I remember, our conversation meandered to the situation in Detroit at the time, particularly the violence that afflicted the Black areas of the city.

I remember one White liberal activist telling me that the Black community of St. Louis is one of the most fragmented she had ever experienced. Maybe it is true that we do not like each other. Maybe that is why we behave toward each other in the ways that we do.

“Of course, you know Black people don’t like each other. They never have,” she said matter-of-factly. I do not know what kind of expression I wore when she said this, but she continued with something like, “Surely, you know this is true. This can’t be the first time you’ve heard this. Black people know this is true.” I must have looked doubtful or incredulous. If so, I did not mean to look that way. I also thought she might not have said this if I were White.

One might think that if anyone were to identify a group riven by dislike that group would be Whites. Were not internecine wars fought for centuries in Europe? Did not Whites cause the two most cataclysmic, destructive wars of the twentieth century, did they not, despite their cultural similarities, fight each other in the United States in the War Between the States, as some called it? But Black people have always felt that Whites, whatever grievances they held against one another, were united in their dislike of the darker races, to use a phrase. This “unity,” as compelling as it was empowering, was something that Blacks felt they needed or wanted in their defense, in their own pursuit of redefinition and liberation. And in one way or another from Marcus Garvey and Hubert H. Harrison to W. E. B. Du Bois and Kelly Miller, from Booker T. Washington and Elijah Muhammad to Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, from Mary McLeod Bethune and Dorothy Height to Johnnetta Cole and Eleanor Holmes Norton, Blacks have always felt that unity has been elusive and, more, lack of unity has been destructive to our communities. Unity has always been the one main political and social virtue in the Black imaginary. As Curtis Mayfield sang years ago, “Why can’t we brothers/protect one another? Know I’m serious/And it makes me furious.” As I was told as a boy, “You best be prepared to fight if you around your people, boy. They don’t know no other way but giving each other a hard time.” I remember one White liberal activist telling me that the Black community of St. Louis is one of the most fragmented she had ever experienced. Maybe it is true that we do not like each other. Maybe that is why we behave toward each other in the ways that we do.

“No,” I said to Maxine Powell, “This is not the first time I’ve heard this. I have heard it many times before.”

• • •

On the Skeleton Coast

Ben Westhoff, a Washington University alumnus, was Big Brother to Jorell¹ Cleveland of Ferguson for eleven years, from the time Jorell was eight until he was nineteen. On August 27, 2016, two years after the police killing of Michael Brown, Jorell was found murdered on a street in Kinloch. He was shot to death in broad daylight. The police solved the killing, but no one was brought to trial for it. Westhoff also managed to figure out who did the murder through dogged investigation.

Westhoff explains early on why he chose to be a Big Brother: “For my brother, sister, and me, public service was a critical part of our upbringing. My mom’s parents opened their home to Hmong refugees, and when Grandpa Shelly retired he taught Hmong children how to write their language. My mom tutored a Vietnamese refuge named Quang for years…. We built houses with Habitat for Humanity, and in high school I organized a volunteer program at a Minneapolis soup kitchen.” (15) He was to the manor (or manner) born, so to speak. He was taught to believe in service.

To be sure, the relationship between Westhoff and Jorell changed over time. Toward the end, Jorell was estranged from Westhoff and hardly saw him, although it cannot be said that Jorell utterly rejected him or even grew to dislike him. Jorell’s family liked Westhoff, especially Jorell’s father. But Jorell clearly felt he was a man at the end and no longer needed the props of his childhood. Westhoff was one of those props. Jorell felt he had outgrown the relationship or that Westhoff could no longer understand his life and the choices he felt he had to make. It is to his credit that Westhoff, in investigating Jorell’s murder, was determined to try to understand Jorell’s life as well as his own.

What drives the narrative of Little Brother is the compulsion, obsession that Westhoff felt about his relationship with Jorell and the need to make it work, even when Jorell, from all evidence, had lost interest in it or was clearly indifferent to whether their relationship had a future.

It is unclear how long someone is supposed to serve in the role of a Big Brother. Little Brother certainly does not make that clear, although the book provides a brief history of the organization. (27-28) Does one sign on for a term of service? How much of an intervention is the mentor expected to make in the family life, the personal life of the child? How are people—mentors and charges—chosen and matched? What is clear from Little Brother is how Westhoff felt about the nature of his commitment to Jorell but not what the organization’s expectations are.

What drives the narrative of Little Brother is the compulsion, obsession that Westhoff felt about his relationship with Jorell and the need to make it work, even when Jorell, from all evidence, had lost interest in it or was clearly indifferent to whether their relationship had a future. The book emotionally hinges on Westhoff’s commitment to the relationship which explains why he is so driven to find out who killed Jorell and why. No reader would question Westhoff’s sincerity, his depth of feeling for Jorell. But one might ask if his emotional intensity is partially driven by the racial difference here. Is Westhoff especially motivated because Jorell is Black? Would he have felt the same level of guilt about the relationship’s rupture if Jorell had been White? As Westhoff writes about his emotional state shortly after Jorell’s death: “I began to lose confidence in the everyday tasks of raising my own boys. If I couldn’t take care of Jorell, what made me so sure I could take care of them? Only one thing was clear: I was a failure.” (104)

It must be remembered that Westhoff was not replacing or substituting for Jorell’s father. Jorell was not a fatherless boy. He was living with his father almost the entire time Westhoff knew him and his relationship with his father was fine. Is it common for Big Brothers to feel this level of responsibility for their proteges who, after all, have families, parents (Jorell’s mother had served time in prison but was still a presence in his life), and siblings? If Jorell’s own family could not save him, why would Westhoff feel that he should have? (“…the impulse to help him consumed me,” writes Westhoff at one point. (83)) Doubtless, he had a strong attachment to the boy, but some readers might feel Westhoff’s attitude comes perilously close to that of the “White savior,” the updated version of the White man’s burden.

(I mean to be neither snide nor glib in noting Westhoff’s racial consciousness. It is a major theme in his book that one must take seriously. At one point he writes “Jorell’s killer was most likely a Black man from Ferguson or Kinloch? Was it right for me, as a white person, to try to get [Jorell’s killer] thrown in prison?” (211) But how can the race of the prison population or prison reform in this instance be some mitigating or exculpatory factor in whether a cold-blooded murderer should be imprisoned for his crime? How is letting Jorell’s killer go free an aid to the community? Does not Westhoff have a moral responsibility here that has nothing to do with anyone’s race? Westhoff’s view is fascinating but also, for me, disturbing.)

In any case, the tale here is not a story of an absent Black father or a neglectful family. In fact, one of the fascinating aspects of the book’s deep and rich journalistic account of Black North County is how much Black fathers or Black men in general seem to be around their families, that is, when they are not in jail, and how much family life and personal loyalty matter to these Black folk, sometimes to their detriment.

The Big Brother/Little Brother relationship is built on inequality as a learning and modeling tool. There is the inequality of the adult and the child, but further there is the inequality of the disadvantaged (the child from a poor background) and the advantaged (the successful or at least competent adult), and the inequality of the emotionally deprived child and the emotionally beneficent adult. This is not a criticism, merely an observation of how the structure of brotherhood works here. These forms of inequality are inevitable, given the philosophy of Big Brother/Little Brother. But they are also seen as innocuous, natural, affinitive, even pedagogically rich, in some ways.

One of the fascinating aspects of the book’s deep and rich journalistic account of Black North County is how much Black fathers or Black men in general seem to be around their families, that is, when they are not in jail, and how much family life and personal loyalty matter to these Black folk, sometimes to their detriment.

But these layers of inequality are meant to showcase the validity of two sociological principles: contact theory and deficit theory. In this instance, Westhoff’s job is to show Jorell the merits, the rewards, the tranquility of White bourgeois life as an alternative to the chaotic, stressful, precarious, institution-poor Black life in Ferguson and Kinloch. Jorell, of course, shows his mentor aspects of his own life as a demonstration of his humanity and to enrich the perspective of the “advantaged” mentor.

This exchange, though, is largely meant to serve the Little Brother which leads us to deficit theory. The life of the working poor is less than the middle class—less materially, less educationally, less socially, less in its emotional range and possibilities, and, most important, less safe. First, through contact, the working poor must be made to see and appreciate this. Then, through deficit theory, this lacking must be compensated for to improve the life of the poor. Jorell seemed to enjoy the times he spent living with Westhoff’s family but in the end did not want White suburban bourgeois life and certainly not to live with Westhoff on any sort of permanent basis, as Westhoff painfully learned from one of Jorell’s candid Facebook posts which he had probably not intended for Westhoff to read. (92-93) Westhoff did not like Jorell’s sugar-laden, fast-food diet, tried to correct it but failed. He did not like Jorell’s study habits, such as they were, as Jorell had no interest in school. He was unable to get Jorell to read books. This Westhoff blamed on “crummy” schools while never explaining what made the schools crummy. Is it the physical plant? Is it the teachers? (Many of the teachers might say that their big problem is unmotivated students like Jorell who do not have a good reason to be unmotivated.) Is it the school board? The school superintendent? Lack of critical race theory? Lack of AP classes? Test scores? Systemic racism? All of the above? Looking at the websites of many of the schools in North County, most of which have Black principals including the Mark Twain Restoration and Wellness Center, the school to which Jorell was sent as a last resort to help him graduate by the age of twenty, I could not immediately discern what made them “crummy.” Westhoff might be right about the schools but I felt he was expressing a cliché rather than persuasively making a point.

After Jorell’s death, Westhoff discovers how little he knew him. He learns that Jorell was snorting heroin, dealing drugs, owned and loved guns, was a gang member, had a hair-trigger temper taking umbrage at the most insignificant slights (as many folks in low-income areas do), was essentially a sort of low-level petty tough and wannabe criminal. (Jorell got into trouble over slights, giving them or wanting revenge for receiving them. Albert Einstein said that the intelligent ignore slights, the strong forgive them, but the weak must revenge them.) This is not the cute, shy, hip-hop-loving boy he thought he knew. Westhoff concludes that poverty causes crime and many of the disadvantageous attitudes the poor have. Of course, the opposite can be plausibly argued as well: that crime causes poverty, as the working poor engage in petty and sometimes violent crimes that involve guns and illegal drugs. These crimes increase their contact with all the bottom-feeder institutions of American life: the police, the criminal justice system, the family courts, prisons, jails and reformatories, minimum wage jobs, and the welfare system. This ensures that these people will always stay poor, angry at and deadly to one another, blighted by fear, avoided as socially incompetent and psychologically radioactive by the middle and professional classes, and stressed, underserved, and punished with injustice, indifference, and misunderstood and fetishized by the bourgeois romance with resistance as the ne plus ultra of authenticity. Just a thought.

What makes Little Brother important and a must-read certainly for St. Louisans is its powerful account of a slice of Black life in our region, a vivid picture of the good and the beautiful and the bad and the ugly of North County, a life cordoned off from the rest of St. Louis as if it were a leper colony. Westhoff’s account of the families, the male bravado, the petty crime, the violence, the art and aesthetic of its rap culture, all of this is worth the price of the book. For what Westhoff reveals is the vast profundity buried in the absurdity of Black urban life that also reveals the inadequacy, hypocrisy, and flawed nature of White bourgeois life. (Poor Blacks murdering each other as they do is a tragedy, but it is also an absurdity because the very people who ought not to see their lives as expendable so often do.) But what is as valuable are the very conceits and assumptions that drive the book, whether or not one agrees with them. Why do we think about each other the way we do and how do various institutions, Big Brothers Inc., social media, small Black independent businesses, large corporate businesses, mediate that thinking? Finally, how much are charity, service, and outreach related to desire? How much are those we wish to help objects of desire and repulsion?

This is not the cute, shy, hip-hop-loving boy he thought he knew. Westhoff concludes that poverty causes crime and many of the disadvantageous attitudes the poor have. Of course, the opposite can be plausibly argued as well: that crime causes poverty, as the working poor engage in petty and sometimes violent crimes that involve guns and illegal drugs.

I reviewed The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace by Jeff Hobbs some years ago for the Washington Post, about the friendship between a poor Black student at Princeton whose father was in prison and his White middle-class friend who winds up unraveling the mystery of Peace’s violent death. (Peace, despite his Princeton education became a low-level drug dealer in Newark and was murdered by rival dealers.) Little Brother is a similar book. Together they might constitute a kind of embryonic genre: the White/Black buddy book where the Black buddy winds up coming to a bad end that can only happen to a Black. I think I referred to Hobbs’s book as a kind of Huck Finn and Jim adventure, going down America’s racial river on the symbolic raft of contact theory. So is Little Brother. (In one case, Princeton University and the other, Big Brothers Inc.) For what turns out to be self-destructive reasons or seemingly so, the Black (the new Jim) decides, “Stop the raft! I want to get off!” And so he departs on the Skeleton Coast where life is precarious, brutish, intense, emotionally challenging, clannish, retributive, and, most of all, short. What does this tell us about race, the American Dream, and the coming of an interracial New Age?

1 Superman’s biological, Kryptonian father was named Jor-El.