Disturbing the Bones Is a Thriller with Big Things on Its Mind

A noted filmmaker and a prolific author team up for a powerful detective fiction

December 30, 2024

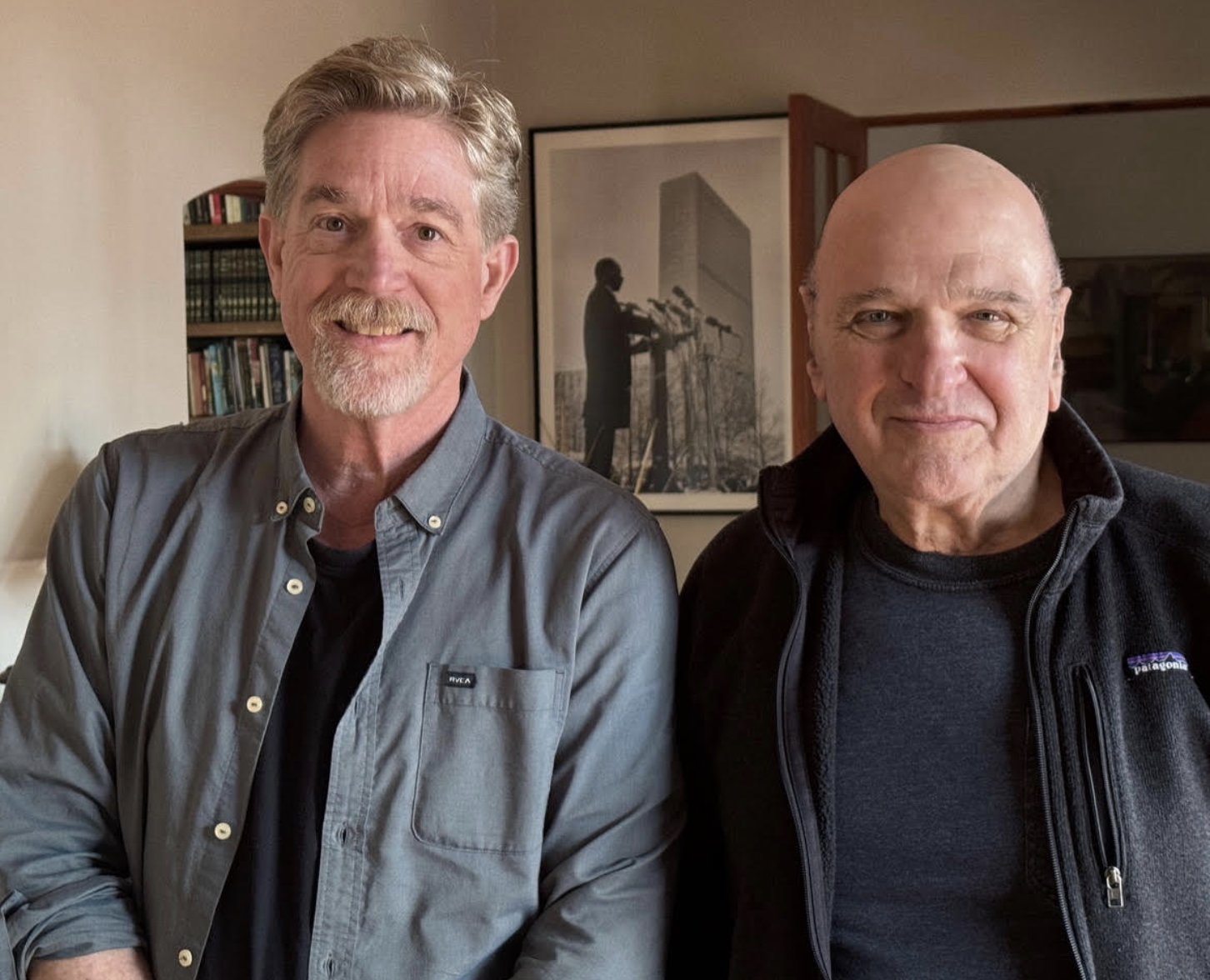

I first met writer Jeff Biggers in 2010, when he was on book tour for Reckoning at Eagle Creek: The Secret Legacy of Coal in the Heartland. We both have an interest in labor history in Southern Illinois, where our families are from, and how the erasure of history strips people of potential choices and action.

Biggers is also a journalist, media go-to, playwright, performance artist, and activist, and the author by my count of ten books, including ones on resistance as “an American tradition” and on Anne Royall, one of America’s first female muckrakers. Before this year, his most recent book was In Sardinia: An Unexpected Journey in Italy, which reminded me of Frances Mayes.

All those books are nonfiction, so I was interested to learn his new book, Disturbing the Bones (October 2024), is not only a novel, but a thriller, and cowritten with Andrew Davis, director of The Fugitive (1993), who has worked in the thriller film mode with Tommy Lee Jones, Harrison Ford, Kevin Costner, Steven Seagal, Chuck Norris, Arnold Schwarzenegger, et al. Chances seem good you will be able to see a movie adaptation of the novel one day.

Disturbing the Bones alternates between Cairo, Illinois, where the two great rivers meet at the bottom of the state, and Chicago, its economic and political engine, 400 miles away at the top. A detective from the city, looking to solve the mystery of his mother’s murder decades earlier in Cairo, must join forces with an archaeologist and her college interns to defeat rogue military and intelligence figures who are dug in (literally) in Southern Illinois with the aim (literally) of taking power on the global stage.

• • •

All narratives might be said to have other things on their minds than what they show us directly. This is certainly true of “socially-conscious” or “social” thrillers, including films such as Jordan Peele’s Get Out, a parable of racial politics and Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, a tale of class warfare. I read an argument recently that Girl With the Dragon Tattoo is a social thriller (with two film adaptations, including the one with Rooney Mara and Daniel Craig) because it portrays rape vengeance in the context of a corrupt legal system.

Davis’s and Biggers’ novel has a lot on its mind too, which might be summed up as a desire to save the world. Yes, the bad guys’ evil plot to destroy Chicago and international diplomacy must be foiled, but the book is also thinking about threats such as nuclear proliferation and the impossibility of “fail-safe” precautions, racism, historicide, and America’s cultural divide. I do not know Davis’ politics, but it gives nothing away to say that the two great mentors of Biggers’ life were William Sloane Coffin and Studs Terkel.

A detective from the city, looking to solve the mystery of his mother’s murder decades earlier in Cairo, Ill., must join forces with an archaeologist and her college interns to defeat rogue military and intelligence figures who are dug in (literally) in Southern Illinois with the aim (literally) of taking power on the global stage.

Disturbing the Bones has a Kamala Harris figure integral to the plot, a Donald Trump figure uncharacteristically less so, a legion of reactionary-racist locals and law enforcement who hope to make America something else, and a small, heroic band of diverse people who believe in science, the airing and preservation of history, and social justice. The book has in mind that good people will win, eventually, though the last pages encourage us to consider the personal costs of Right Action and whether evil can ever be contained. A sequel is indicated.

• • •

I went to two readings for the book, at a Barnes & Noble in Fenton, Missouri, on October 29, and at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, on October 30. Jeff Biggers and Andrew Davis were doing more than two dozen promotional events, separately and together, from Santa Barbara to Cincinnati. These were Biggers on his own.

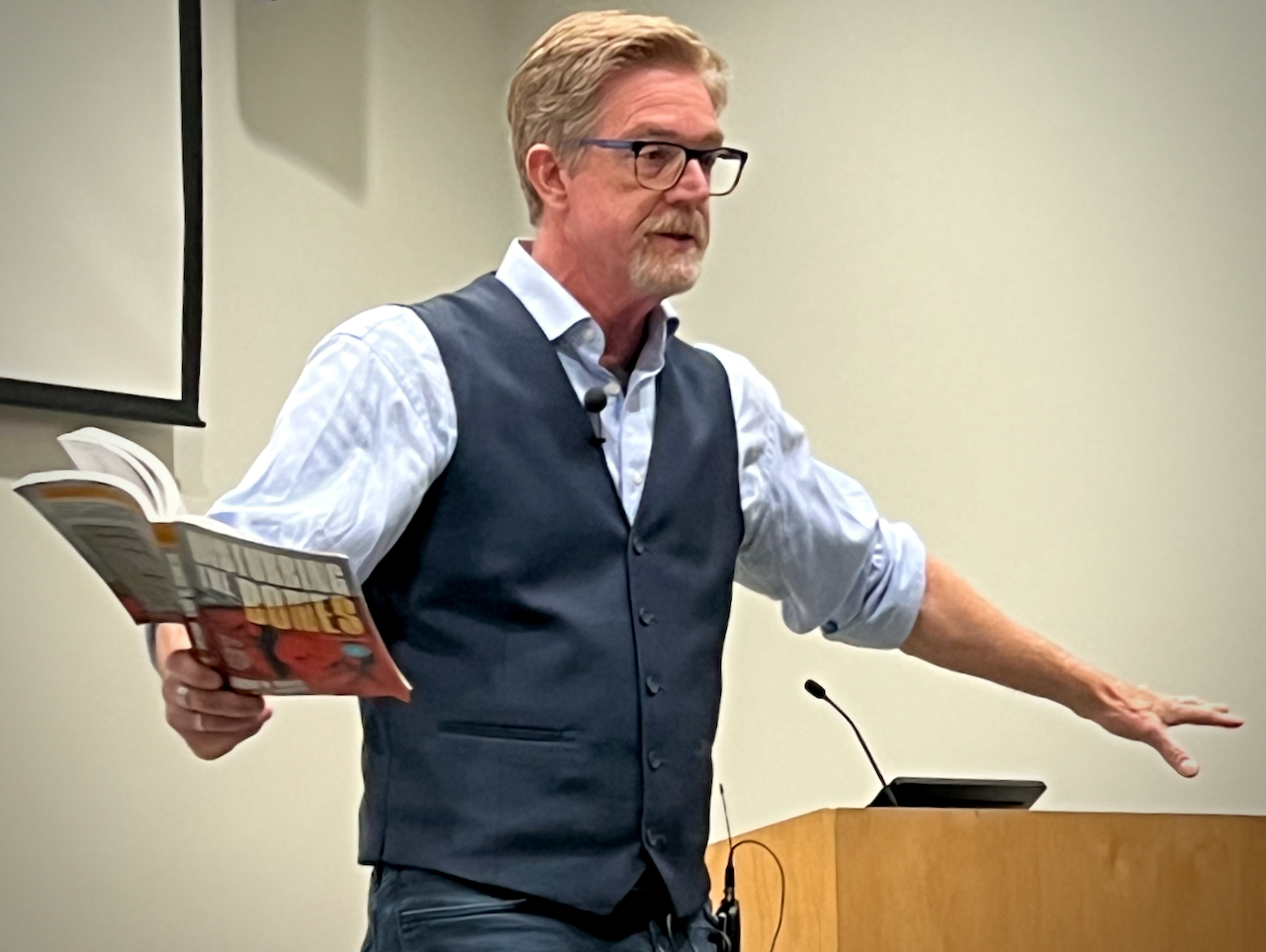

Jeff Biggers has never done the standard bookstore/campus event for his books: intro, reading, Q&A, thanks. His are interactive, theatrical performances, in which he asks questions and listens to answers, voice-acts passages, moves around, makes connections with other ideas, and introduces people with their own projects. Often there is music or other media. His readings become additional opportunities for the connection, education, and activism that have been his professional life, and he is incredibly generous and inclusive. At that reading in 2010, he spent at least five minutes of his time unexpectedly reading from my novel.

I do not know Davis’ politics, but it gives nothing away to say that the two great mentors of Biggers’ life were William Sloane Coffin and Studs Terkel.

The event at SIU’s Morris Library was not actually billed as a reading, but as a “show,” titled, “From Southern Illinois to Hollywood: Bringing, history, culture and stories to the stage.” Singer-songwriter Isaiah Cunningham performed original music as a soundtrack to something like an old radio show. Some of Biggers’ co-performers, who were to drive up from Cairo, were unable to be there, so an undergraduate classics major was conscripted to read alternating dialogue with him.

The auditorium where the show was held is used in the novel, and in both life and fiction the crowd was sizeable, various, and reflected the region. I met a lefty bookstore owner, conservationists, a university administrator, and big guys in insulated hunting jackets, who I guessed had been drawn by Andrew Davis movies such as Under Siege, not by Biggers’ progressive activism.

“Once upon a time, when coal was hot…I was the anti-coal guy,” Biggers told the audience. “I drove around getting death threats. It was exciting…going around back roads and being chased.” He laughed. “I’m making all that up, of course.”

“I’m a muckraking journalist, I’m a cultural historian, and then [I was] thrown into this whole world of Hollywood and…this world of fiction writing, and a crazy idea for a story I fell in love with. [Davis] said he wanted to base it here in Southern Illinois. And I felt like [we could introduce] our history…as we begin to tell the story.”

He said he would start the evening by playing a trailer on a screen at the front of the auditorium, “because when you make a novel with Andrew Davis, who gave us not just The Fugitive and Holes, but Under Siege, The Package, Perfect Murder, 12 amazing films…you also get to have a trailer with your book.”

The trailer—driving, suspenseful music over temporarily-shot scenes, since this movie is still in pre-production— had played only five seconds when an older lady called out, “It looks good already!” and the audience laughed.

• • •

Biggers said this night’s show was sponsored by the Shawnee National Park and Climate Preserve.

“They’ve been in existence for 20 years,” he said, and that when his kids were little, his family got tired of having to drive to national parks like Teton, “when we had a national park in our own backyard. And so I have to thank the National Park for sponsoring this tonight.”

I felt disoriented. The Shawnee National Forest of Southern Illinois was my first biome, and there is no national park in the state of Illinois. Could I have missed something that politically momentous?

The event at SIU’s Morris Library was not actually billed as a reading, but as a “show,” titled, “From Southern Illinois to Hollywood: Bringing, history, culture and stories to the stage.”

Biggers spoke of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers coming together at Fort Defiance, in Cairo, “and the visitor center, thanks to the Shawnee National Park, is fabulous at Fort Defiance. If you get lost, there’s a cultural section where we learn about Chris Jackson, he was the lead of the Hamilton musical [nominated for a Tony for his role as George Washington] on Broadway, coming from Cairo, and Henry Townsend, who led the Chicago blues, and Mama Yancey, who lit up Carnegie Hall, like Isaiah [will] one day in New York City, or we go over to Tyrone Nesby, who led the NBA, or Caroline Smith, the great diver from Cairo. So many people from this region, it’s all part of our national visitor’s center, we’ve got six of them around Southern Illinois….”

He was right that there is no other place in America like the confluence of its two biggest rivers. But in reality Fort Defiance is a small Illinois state park, with a concrete observation platform shaped like a wheelhouse of a river boat and not much else, except picnic tables and sometimes people fishing from the riprap for catfish and striped bass.

“If you’d like to visit the Shawnee National Park,” Biggers said, “just go online and type it in, and it’ll appear before you, because it’s the best idea Illinois has ever had. Shawnee National Park and Climate Preserve, thank you very much.”

The audience applauded. I wondered if I had slipped into an alternate reality.

• • •

Andrew Davis had this idea [for the screenplay that became the novel], eons ago,” Biggers told the audience. “[H]e said, ‘I love the Koster site they found in the 1970s; Northwestern students came down [to work it].’ And…we know about Cahokia,” Bigger said, ticking off Mounds Culture sites. “We know about Kincaid, over where we’re from… and of course across from Cairo you’ve got Wickliffe. There’s just so much archaeology. Cahokia, of course, [was] the largest city north of Mexico City, up until 1863.

“We have an archaeological site [in the novel] where they find contemporary bones,” he said.

A highway is being built for national-defense purposes, from the St. Louis area to Cairo, where there will be a new military installation. Biggers said that in real life Eisenhower determined that a certain percentage of federal funds for highway construction can be used for archaeology. In the novel, as a result of the highway route, what may be the largest Archaic civilization in North America is found at varying depths.

The trailer—driving, suspenseful music over temporarily-shot scenes, since this movie is still in pre-production— had played only five seconds when an older lady called out, “It looks good already!” and the audience laughed.

“That’s where they find these [recent] bones. So, our [protagonist] Molly…who’s from Cairo [but who] went off…to Yale…then to do her doctoral thesis in Vietnam and Cambodia, [is] one of the leading experts in LiDAR technology, ground penetrating radar. The technology with archaeology is amazing; they use drones…they’re almost as high-tech as military intelligence.

“She comes back to do this dig, as a favor, because she’s the hometown girl. She wants to try to understand her roots. She’s white, from Cairo. And she wanted to get out and never come back, because there’s a little secret she has to deal with, and that’s that her grandfather was in the Klan. They called them the White Hats in Cairo.

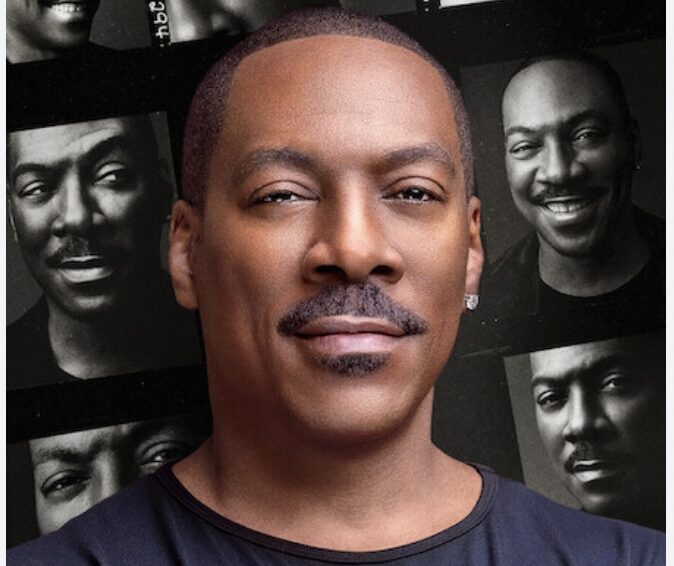

“[S]he sends these bones up to the FBI in Chicago, and there they call a Chicago detective [because] the DNA matches [with his]. [T]hink Denzel Washington…and he has to come back to Cairo, a place that he left as a young man. His mother was a writer and civil rights activist [who moved] to Chicago, but she came back for a wedding and never returned. He grew up thinking he’d been abandoned as a child, that his mom maybe had run off with another man, that something happened they couldn’t explain…was she missing, was it a cold case? Now they have her bones. And he has to work with the granddaughter of the Klan to produce evidence.”

“Another woman [comes] in—think Rachel McAdams; you can do that when you work with Andy Davis—and she [is] a special military intelligence officer, who has come down from Scott Air Force Base. She wants to understand what…these young archaeologists are doing with all this high-tech information and drones.”

“Randall [the detective] comes back to Cairo and is shocked at what he sees. […] What happened, where did that go…why has that been torn down, why did they strip this? […] And his aunt is there to explain: There is more than what you see. She’s the town librarian, giving out books to the whole county; she’s the person who is the keeper of the stories. And perception of course is very different from reality.”

• • •

In the novel, a Black woman becomes president. “We wrote that three years ago,” Biggers told the audience a week before the presidential election. “It actually happens. […] But then, not everyone’s happy, because there’s a global crisis. And she wants to go back to Chicago, the south side, to Stagg Field, where the atomic age began in 1942…and we began the age of nuclear weapons. She says, ‘Let’s go back to Chicago, it began there, it will end there, and we’ll have [a] great disarmament summit.’ But there’s a retired general in Alexander County who doesn’t want that to happen.”

“Our rogue general is someone who has worked with Andy on many of his films, including The Package and Under Siege. Who do you think would be a good rogue general who wants to end a peace summit?”

“Gene Hackman,” a man in the audience said.

“Nope,” Biggers said. “Who played counter to Gene Hackman?”

“Tommy Lee Jones,” someone else said.

“Tommy Lee Jones,” Bigger said. “So it’s Tommy Lee Jones fighting against Denzel Washington and perhaps Emma Stone, is what we’re looking for. And then Rachel McAdams is…this evil intelligence agent, who we don’t really know what side she’s on.”

• • •

“[We’ve written] an unabashed anti-war novel,” Biggers told the audience near the end of the show, “and that’s why we wanted to use story to talk about things perhaps we can’t talk about in this room, or with our families, or even during the election. And that’s the role of storytellers.

“And that’s…why I envision the Shawnee National Park [ie, it does not yet exist]. I have to see it, I have to tell stories about it, I have to re-story, and then it’s going to happen. Not as a utopic idea, but as the natural progression of all natural things…we re-story and tell stories to make things real.”

“Restorification,” he called it later.

After Kamala Harris’s defeat, the book no longer felt like a prediction, but an alternate history novel. I asked Jeff Biggers by email about socially-conscious thrillers as a genre, and whether they can affect the world.

I felt disoriented. The Shawnee National Forest of Southern Illinois was my first biome, and there is no national park in the state of Illinois. Could I have missed something that politically momentous?

“I’m always reminded of Thornton Wilder’s The Eighth Day, set in Southern Illinois, of families torn apart by murder and its fallout,” he replied. “The Jenkins and Moore families and their histories are not just entwined, but contradictory and essential to understanding our characters today. […] As you and I discussed, no honest fiction can be based in Southern Illinois, and Cairo in particular, without a reckoning with our social divisions and the twisted history of racism in all its brutalities and the courageous acts of defiance and still small possibilities for justice.

After Kamala Harris’s defeat, the book no longer felt like a prediction, but an alternate history novel. I asked Jeff Biggers by email about socially-conscious thrillers as a genre, and whether they can affect the world.

“But the model for Disturbing the Bones, as a political thriller—or what Andy referred to as a ‘thriller with an urgent message’—might be more like Eugene Burdick and Harvey Wheeler’s bestselling Fail-Safe, published in 1962, and Peter George’s Red Alert, about the hair-raising illusions of our nuclear weapons. Call it a natural born thriller in the Atomic Age, because a crisis is always inevitable, even as you read this; Burdick called it the monster, the twin forces of evils launched by science and the state. These have always been themes for Andy.

“Can such stories improve the world? Fiction, like narrative nonfiction storytelling, can certainly allow us to have conversations and gain a new view of the world that we might not be able to have in real life; for us, it’s also an opportunity to ask those difficult and provocative questions, and move our reader to their edge of their seats.”

• • •

In 1944 Edmund Wilson wrote an essay for The New Yorker called, “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?” He thought the genre had peaked with Poe and Dickens but admitted that in the decades between the world wars it had become “more popular than ever before.”

“There is, I believe, a deep reason for this,” he said. “The world during those years was ridden by an all-pervasive feeling of guilt and by a fear of impending disaster which it seemed hopeless to try to avert because it never seemed conclusively possible to pin down the responsibility. Who had committed the original crime and who was going to commit the next one?”

“Everybody is suspected in turn, and the streets are full of lurking agents whose allegiances we cannot know. Nobody seems guiltless, nobody seems safe; and then, suddenly, the murderer is spotted, and—relief!—he is not, after all, a person like you or me. He is a villain…and he has been caught by an infallible Power, the supercilious and omniscient detective, who knows exactly how to fix the guilt.”

Never underestimate the power of a fiction.