It was the 1960s. NASA was gearing up to send Americans to the moon. And the University of Kentucky, in Lexington, was sending freshman students to the 23rd floors of its newly opened Kirwan-Blanding dormitory towers, the tallest buildings in the state and probably in the entire Ohio Valley region.

Fast forward to the spring of 2020. In mid-March, like universities all over the country, the University of Kentucky (UK) sent its students home to finish their spring semester classes online. Classrooms, dormitories, and faculty offices are eerily empty. Only one site on campus hums with activity. Behind chain link fences, employees of the demolition company Sunesis Environmental are tearing down the soaring Kirwan-Blanding towers and the rest of the eleven-building complex that has been a landmark of the University of Kentucky for over fifty years.

Observing the progress of the demolition work, as I have been doing every couple of days when I ride my bicycle through the deserted campus, has a certain horrid fascination. First, columns of scaffolding climbed the sides of the towers, like some kind of metallic ivy. Then the roof of the first tower disappeared, leaving it looking as if it had been given a bad haircut. A giant construction elevator started crawling up and down the side of the doomed structure, like a spider sucking the blood of a victim. Now the walls of the top stories are disappearing at the rate of one story per week, leaving only a metal skeleton. Meanwhile, work on the second tower has begun. How it must be suffering, having seen what has already happened to its mate.

A giant construction elevator started crawling up and down the side of the doomed structure, like a spider sucking the blood of a victim. Now the walls of the top stories are disappearing at the rate of one story per week, leaving only a metal skeleton.

The decision to demolish these buildings was taken several years ago, before the word “coronarivus” had entered our everyday vocabulary. Built in an era when student expectations for comfort and privacy were very different from what they are today, the 1960s-era dormitories would have cost $126 million to renovate, according to university officials. Demolishing them was originally estimated to cost $15 million and is now expected to be even cheaper since the closing of classes has allowed work to proceed without having to be scheduled to avoid disrupting campus activities.¹

Somehow, though, the sight of the Kirwan-Blanding towers shrinking as they are literally deconstructed, brick by brick, in the midst of the worst national crisis our country has experienced since World War II, seems sadly symbolic. When they were put up in the 1960s, the Kirwan-Blanding Towers were a confident bet on the future of the University of Kentucky and of the country and the world. Now, as they disappear, no one can be sure of what the future holds for American higher education, for America as a whole, or for the planet.

Needed to house the growing number of students from the Baby Boomer generation, the new dormitories represented an investment, not just on the part of the University of Kentucky, but on the part of the nation as a whole. Galvanized by worries that the United States was falling behind its Cold War rival, the Soviet Union, which had taken the lead in the space race in 1957 by launching the first artificial satellite, politicians across the spectrum supported investment in education. The federal government and states financed the expansion of campuses all over the country. Up-to-date dormitories were a key element of that program.

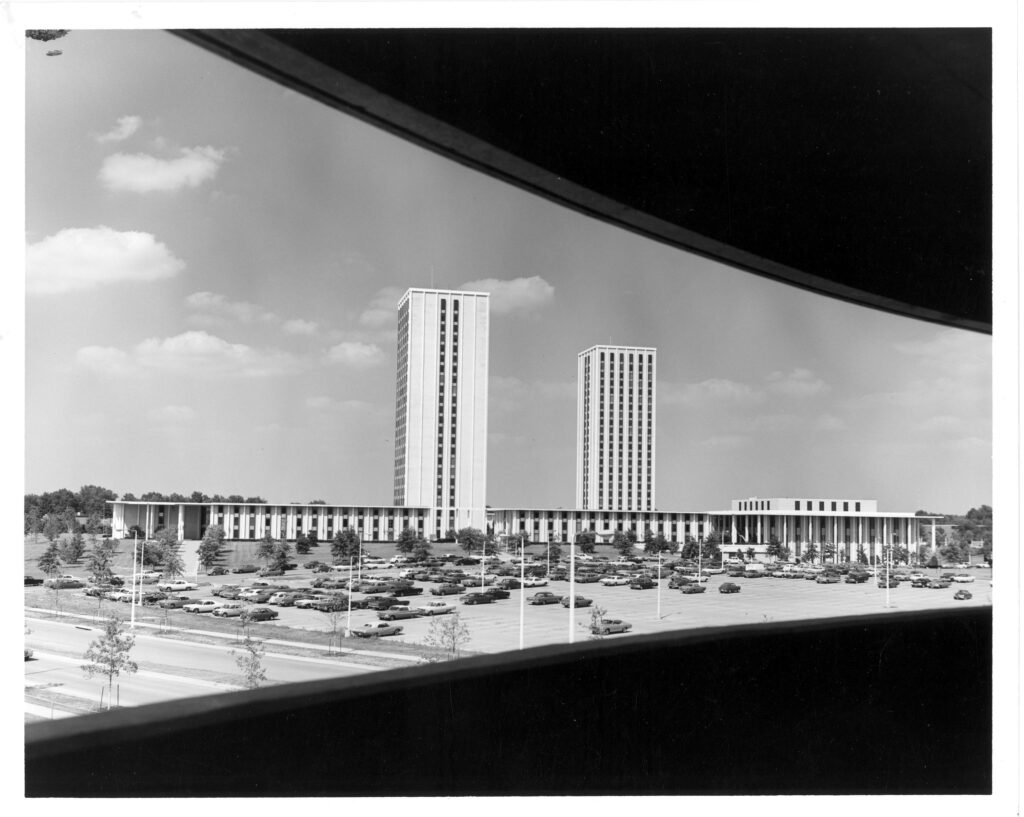

The Kirwan-Blanding complex soon after completion. (Photo courtesy of University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center)

Built to house 2,664 students, with a dining commons that could seat 980 at a time, the Kirwan-Blanding complex was meant to solve the practical problem of campus housing. But the project had a bigger meaning. With their modernist designs, buildings like these were a statement that universities were leaving ivy-covered halls behind and embracing the new technology and sleek geometry of the future.

Previously a small southern institution known primarily for its successful basketball team, the University of Kentucky was determined to make its new housing complex a statement of its ambition to become a major research campus. To design the new dormitories, UK hired the best-known American “starchitect” of the day, Edward Durell Stone. Stone was at the height of his fame, celebrated world-wide for buildings such as the American Embassy in New Delhi, India, and the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.

With their modernist designs, buildings like these were a statement that universities were leaving ivy-covered halls behind and embracing the new technology and sleek geometry of the future.

Stone and his firm were major contributors to American university architecture in the 1960s, designing eight entire campuses and buildings for many more. Stone believed that “students reflect their surroundings, and that the appearance and the feeling of one’s surroundings make a great deal of difference.”² Inspired by Christ Church College at Oxford and Harvard Yard, Stone laid out a complex of buildings at Kentucky that gracefully married modern high-rise construction with centuries-old academic traditions. Grouped around a large open space with trees and shaded benches, the Kirwan-Blanding complex, in spite of the soaring height of its towers, had the feel of a medieval cloister.

Unlike the University of Kentucky’s other high-rise building from the 1960s, the 18-story “brutalist” Patterson Office Tower where I have had my office for more than forty years, Stone’s Kirwan-Blanding Towers looked light and airy, not massive and heavy. The beige-colored bricks on their exterior and the vaguely Indian decorative motif repeated on the walls of all the buildings in the complex unified the towers with the low-rise structures around them, while the difference in height between the skyscrapers and their three- and four-story neighbors provided variety. At a conference held to memorialize Stone’s achievement in 2019, his biographer Mary Anne Hunting called the Kirwan-Blanding complex one of the architect’s most successful achievements.

It was always a pleasure to stroll through the complex, an oasis separated from the rest of the campus. In 2013, Lexington journalist Tom Eblen took a walk through past the buildings and caught the atmosphere they created: “The moon was rising between the towers, which were bathed in the glow of the setting sun. Students were all around the buildings, studying among trees and flowers or throwing Frisbees and footballs.”³

Elegant as they appeared on the outside, the towers were not so comfortable for their inhabitants. When the decision was taken, in 2015, to close them and start preparing for their demolition, local journalist Megan Marcum, a former resident, remembered them as “dimly-lit, cinderblock shoeboxes.” ⁴ The rooms were small, so those who lived in them “know just how to maximize your space,” Marcum wrote. “Double-stacked hangers, storage boxes galore, and six classes worth of textbooks and notes crammed into a single desk drawer.” Sound insulation was not a concept: students could converse with neighbors through the walls.

Inspired by Christ Church College at Oxford and Harvard Yard, Edward Durell Stone laid out a complex of buildings at Kentucky that gracefully married modern high-rise construction with centuries-old academic traditions.

As was customary in 1960s campus housing, students on each floor of the buildings shared common bathrooms and showers with “musty, paint-peeled tiles,” as Marcum remembered. The elevators were “unnervingly loud, and incredibly slow,” and prank fire alarms often forced residents to scurry down many flights of stairs. Nevertheless, “despite the leaky ceilings, thin walls, and general lack of cleanliness, you made some of your best friends from college in those musty little shoeboxes that we called dorms.”

By the early twenty-first century, what had seemed futuristic fifty years earlier had come to seem hopelessly out of date. In the 1960s, middle-class students came to Kentucky’s campus from small, boxy tract homes and poorer ones from shabby Appalachian cabins that lacked indoor plumbing, as Harry Caudill’s classic Night Comes to the Cumberlands told the country. By the 2000s, better-off students grew up in McMansions in prosperous Lexington and Louisville suburbs and housing standards had risen even in the poorer parts of Kentucky. “Ninety-three percent of our freshmen have never shared a room,” an administrator told the local newspaper in 2017, explaining why UK had decided that the towers could not be renovated.

“Stone’s Kirwan-Blanding Towers looked light and airy, not massive and heavy.” (Photo courtesy of University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center)

The University of Kentucky received national publicity in 2012 when it became one of the first campuses in the country to sell its entire on-campus housing operation to a private company, which engaged itself to replace older dormitories with modern, state-of-the-art residences.⁵ In the past ten years, a $450 million frenzy of dormitory construction has utterly transformed UK. Every open space in the central campus seems to have been covered with dormitories or new, high-tech classroom buildings. A luxurious new $200 million student center opened in 2018. Until the pandemic hit, sidewalks on this new “high-density” campus felt as crowded at class-change times as the New York subway at rush hour.

The interiors of the new dormitories are unquestionably more comfortable and “user-friendly” than the ones that date to the 1960s or earlier. They provide private bedrooms and bathrooms with granite countertops, as well as spaces for social gatherings and classrooms to make them “living-learning environments.” In place of traditional dining halls, many of them have café-like chain restaurant outlets. From the outside, however, the new corporately-built dormitory buildings are uniformly undistinguished. They could be part of any office park or apartment complex in the country. They certainly do not convey the sense of excitement about the future that the Kirwan-Blanding complex did in the 1960s.

The changes in expectations that rendered the Kirwan-Blanding complex obsolete reflect the fact that today, or at least until everything changed in mid-March 2020, students arrive on campus as “customers,” taught to regard their costly education as an investment in their personal future more than in a national one. The proportion of the cost of college covered by state and national governments has shrunk drastically since the Kirwan-Blanding days, and most students leave college saddled with debts that keep them focused on their own financial prospects.

When the decision was taken, in 2015, to close them [ the Kirwan-Blanding dormatories] and start preparing for their demolition, local journalist Megan Marcum, a former resident, remembered them as “dimly-lit, cinderblock shoeboxes.” … Nevertheless, “despite the leaky ceilings, thin walls, and general lack of cleanliness, you made some of your best friends from college in those musty little shoeboxes that we called dorms.”

Now, as the catastrophe of the coronavirus pandemic unfolds across the world, students, professors, and campus administrators lie awake at night, wondering whether the American model of higher education can survive. The eateries and meeting spaces in UK’s newest dorms were designed to promote the very opposite of the “social distancing” that may have to be imposed to allow the university to reopen.

For the moment, university leaders continue to express optimism that face-to-face classes will resume in the fall. Whether this will be possible without reliable tests for the virus or a vaccine to protect teachers and students remains unclear. There is a very real and frightening prospect that our new high-tech dormitories will be standing empty, as the Kirwan-Blanding buildings did for five years before the current demolition project started.

The only thing we know for sure at the moment is that the Kirwan-Blanding complex will be gone by the end of the year. In fact, a recent article in the local newspaper indicated that the evacuation of the campus has allowed the work to proceed faster than expected. Not having to worry about noise disrupting classes as they dump rubble from the buildings’ upper floors down the elevator shafts to the basements, where it will be buried, the workers of Sunesis Environmental are well ahead of schedule and the job will come in well under budget.

The construction workers are no doubt happy to have jobs; one hopes they also have an adequate supply of masks to protect them from the asbestos with which the buildings were insulated and which prevented the buildings from being demolished by the quicker process of “implosion,” as the university originally proposed.

By the 2000s, better-off students grew up in McMansions in prosperous Lexington and Louisville suburbs and housing standards had risen even in the poorer parts of Kentucky. “Ninety-three percent of our freshmen have never shared a room,” an administrator told the local newspaper in 2017, explaining why UK had decided that the towers could not be renovated.

Long-range plans, announced before the coronavirus crisis, call for the Kirwan-Blanding complex to be replaced by a green space and a new 500-student dormitory. Those plans assumed that the university would be in a healthy financial condition and that demand for on-campus housing would continue to grow, as it has for the past decade. Now those assumptions look wildly optimistic. The site of the Kirwan-Blanding complex may remain vacant for many years to come.⁶

Whatever happens to the space from which the Kirwan-Blanding Towers will soon be gone, their disappearance at this particular moment cannot help looking like a sad sign of the times. They were built at a time when American education and the society that supported it aimed for the stars. At the moment when the towers were definitively condemned as unsalvageable, that vision had changed to a more terrestrial one of helping students prepare to fulfill their private ambitions. Today, when the site of the towers risks being left as nothing but an empty lot, both hopes for a better society and for better individual futures seem to have vanished.