In February 2015, Serena Williams surprised the world when she announced that she would return to Indian Wells, a tournament she had boycotted permanently. In 2001, a predominately white crowd booed and harangued the then 19-year-old the entire match because they believed that her sister Venus had pulled out of a match at the last minute to avoid playing Serena in the semifinals. After winning the tournament, distraught and traumatized, Serena wept in the locker room for several hours. For years, Indian Wells officials begged her to return. For thirteen years she refused. In February 2015, she had a change of heart after reading Nelson Mandela’s autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom (1995).

The brilliant sports writer Howard Bryant eloquently outlined the rules of racism and reconciliation as follows: “always convinced of their own purity, many white observers too often expect African Americans to absorb racism-induced traumas as isolated incidents deserving forgiveness and forbearing, to dismiss the idiot few and always remember the friends more than the foes.”[1] For Bryant, this is contemptible. Victims are expected to extend the sentiment and gesture of reconciliation; the uncooperative sufferer is labeled bitter, even punished until they come around and make America feel good.

Perry Wallace’s traumatic journey as the first African American to play in the South Eastern Conference (SEC) seems to follow a similar pattern. Even as a young man he understood that bitterness would only earn him scorn. In fact, Wallace’s story may be astonishing to today’s reader who annually watches the University of Kentucky trot out five blue-chip African-American basketball freshmen in hopes of capturing a national title. Ironically, most of the football and basketball players in the SEC are African-American, which previously was a whites-only conference that resisted integration. The Kentucky of Perry’s era did not have a remote chance of starting five freshmen—and certainly not a single African-American player. The very same school 50 years ago would have disbanded the program at the thought of doing such a thing. Few current black SEC players know that they have Wallace to thank for his pioneering efforts. Wallace’s inner strength and resolve to withstand unimaginable strife and abuse to break racial barriers deserves more notice.

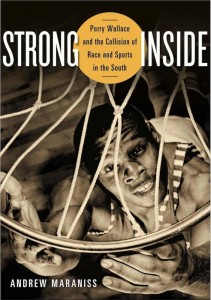

In Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South, author Andrew Maraniss, a former member of the Vanderbilt University athletic department, tells the story of Perry Wallace’s historic success in breaking the SEC color line. Maraniss is perhaps the best person to write about Wallace’s historic trials and tribulations and his journey to desegregate SEC basketball, because he wrote about Wallace while he was an undergraduate at Vanderbilt. He also interviewed Wallace and at one time was director of media relations for the Vanderbilt Athletic Department. His knowledge of the institution and its culture, along with his access to key archival material, prepared him to tell as comprehensive a story as possible. The book falls within the trajectory of recent books about race and sports like Kenneth L. Shropshire’s Sports Matters: Leadership, Power, and the Quest for Respect in Sports (2015), Jennifer H. Lansbury’s A Spectacular Leap: Black Women Athletes in Twentieth Century America (2014), and the James Conyers, Jr. edited book Race in American Sports (2014), among others.

Strong Inside is a story that reveals Perry Wallace’s perseverance over enormous obstacles and implacable hatred. It exemplifies how African Americans have traditionally turned victimization into heroism. Wallace’s story is also about growth and forgiveness, inner strength and resolve. Andrew Maraniss writes a book that assembles the voices of many people closely involved with Wallace’s four years at Vanderbilt University from Chancellor Heard to head coach Skinner and journalists. In some ways it is also the story of the South, an academic institution, and the blindness of whites—good and bad—to the pain suffered by African Americans in a racially hostile environment. The absence of interviews with Wallace’s white teammates is keenly felt by this reader. Besides the unsung pioneer Godfrey Dillard, the voices of the players go unrecorded. But to his credit Maraniss manages to give the narrative the feel of myriad voices. Especially prominent is the voice of Chancellor Heard abhorring the discriminatory treatment of Wallace and his fellow black students, although this did not alter Vanderbilt’s indifference to Wallace’s plight. At times, one wonders if Maraniss’s prior employment and affiliation as an alumnus made him go easier on Vanderbilt than he should have.

The absence of interviews with Wallace’s white teammates is keenly felt by this reader. Besides the unsung pioneer Godfrey Dillard, the voices of the players go unrecorded. But to his credit Maraniss manages to give the narrative the feel of myriad voices. Especially prominent is the voice of Chancellor Heard abhorring the discriminatory treatment of Wallace and his fellow black students, although this did not alter Vanderbilt’s indifference to Wallace’s plight.

Strong Inside begins in Nashville, Tennessee, with the message it ends with: “Forgiveness.” The first chapter is curt and to the point. Wallace’s white Vanderbilt teammate Bob Warren is on his way to meet him 40 years after their playing days. As his cab speeds through the streets of Washington, Warren rehearses what he is going to tell Wallace. Not because of what he did to Wallace, but for what he failed to do as a teammate, student at Vanderbilt, and as a citizen to help to prevent the abuse Wallace endured. Warren’s nine years in the American Basketball Association made him familiar with his black teammates which altered his perspective on the world and in the process “it dawned on Warren what hell one of his brilliant hardworking teammates …Perry Wallace, must have been going through” as the first and only African-American player in the SEC. When Warren arrives, the first words he says to Wallace, whom he had not seen in 40 years, were: “Forgive me, Perry. There is so much more I could have done.” This moment sets the tone for the book. The subsequent chapters introduce readers to Perry Wallace the person, Nashville the city, and Vanderbilt, smug in its white Southern glory and its sense of being the progressive New South. We learn of Wallace’s struggles there, his presumed bitterness about what he went through, and his honored return many years after his playing days. The early chapters introduce readers to an extremely bright, athletic, religious, and sensitive young man whose skills and interests extend beyond the basketball court to include music and engineering. Wallace’s early loves were the trumpet and basketball, both of which he gradually mastered. The trumpet required endless hours of practice, as did basketball, spending countless hours on the court learning to leap; by the time he was 12 he had learned to dunk. Basketball he says, offered him “a passage to freedom and accomplishment in a society engineered to limit both.” Dunking he says, “was like a freedom song.”

The son of Perry Wallace, Sr. and Hattie Haynes, Wallace grew up in Nashville and began his formal education in 1954, the same year as the historic Brown v. Board of Education school-desegregation decision. His mother worked as a cleaning lady in downtown Nashville. His father owned his own brick-cleaning business and was a pioneer in his own rite, as very few black men in the 1950s in the South owned their own business. This allowed Wallace, Sr. to move his family into an integrated neighborhood. Young Perry developed a broad view of the world and its possibilities, cultivated from reading Life and Redbook, magazines his mother brought home from work. Wallace believed all was possible through education.

And, on the basketball court, his incredible leaping ability earned him a spot on one of the best high school basketball teams in Nashville, the Tigers of all-black Pearl High School. No stranger to racial “firsts,” Wallace’s high school won the first integrated state championship in the history of the state of Tennessee in 1966. He was also no stranger to discrimination. Although his Pearl High Tigers won the title, their star player was snubbed in the MVP voting.

The next few chapters focus on Wallace’s recruitment and his desperation to leave the South. He wanted a school with a great academic reputation along with great basketball; he wanted to integrate and participate “in this microcosm of American society,” so he chose Vanderbilt University. In addition to his parents being able to see him play and the excellent engineering program, the final factor in Wallace’s decision to attend Vanderbilt was his belief that “Coach Roy Skinner [was] a very sincere person and the fellows on the Vanderbilt team [were] the nicest [he] met during all [his recruiting] trips.” However, he was not eager to become a pioneer in the SEC as the first black player.

Shaking things up was nothing new for Wallace, and his experiences growing up in the South (Nashville) helped prepare him for the experience of integration. Although he knew the South was a dangerous and inflexible place, the hardships he endured surprised him. Fortunately, he did not begin his journey alone, as he received a gift from Detroit named Godfrey Dillard, who would accompany him through the first two years of the journey to integrate the SEC.

The appearance of the colorful and proud Dillard accelerates the story. His presence confirms Maraniss’s claim throughout the book that change is not an isolated event and there is never a singular individual or moment that produces change. What might be deemed a weakness of the book actually works well in making the point of why racism continues to thrive. The Vanderbilt players and coaches claimed they were largely oblivious to the harassment Wallace and Dillard received on the road as freshman. The pair had to look out for themselves.

Maraniss is to be commended for making Godfrey Dillard such a significant part of the Wallace’s narrative. Dillard, who signed with Vanderbilt seven days after Wallace, is often a forgotten figure. A native of Detroit, Dillard was not your typical African-American recruit of the 1960s. He attended an integrated Catholic school in Detroit, and unlike Wallace, he wanted to go to the South. His “reverse migration” was about becoming “the SEC’s first black ballplayer” it “was the only reason [he] wanted to head south.”

Godfrey Dillard had grown up seeing “accomplished blacks and whites living side-by-side in what was increasingly becoming a very integrated, progressive neighborhood.” He was the perfect pairing for Wallace who knew the South and its rules. Godfrey said: “In my neighborhood I saw examples of black men who could succeed … So as a young person, the idea that the Afro American could not succeed was not an issue to me.” What Vanderbilt and Skinner did not fully realize is that when they signed Dillard they were getting more than an athlete, Dillard “considered himself a political figure” in high school but at Vanderbilt his inchoate activism does not play well. He saw himself as being in the vanguard of the movement to break racial barriers, while his friend Wallace reluctantly assumed this position. But together Dillard and Wallace were a good balance, teaching one another valuable strategies.

For all the good Maraniss’s achieves with his focus on Dillard, how he portrays Dillard’s failure to make the varsity his junior year after recovering from an injury is disappointing. Maraniss only hints that Dillard’s “Detroit style” (he talked a lot on the court and wore Jackie Robinson’s number 42) and his role as outspoken student leader making life more habitable at Vanderbilt for African-American Students made his presence on the team “complicated.” African-American students openly and often endured racial insults from professors in class, isolation from social life, and insults from drunk white students on the weekends yelling to them things like: “Nigger, what are you doing here?!” Taking away basketball from Dillard was the only way to get the politically outspoken Dillard to leave Vanderbilt.

Maraniss leaves the question of the discrimination against Dillard for readers to interpret. This approach is a serious flaw. Maraniss is reluctant to harshly critique Skinner’s treatment of Dillard, despite conceding that the player chosen over Dillard, Rick Cammarata, was “no basketball star.” Instead he uses assistant coach Jerry Southward to explain Skinner’s decision as one driven by “Godfrey’s style [not lending] itself to Skinner … [and Godfrey being] a little more flashy than Roy probably was comfortable with.” Even Southwood admits that the demotion “was a way of Skinner showing Dillard an early exit from Nashville.” Outraged that the coach discriminated against him, Dillard left his friend Wallace to suffer racist southern fans alone. Southwood admits that Dillard was “run out of the program” in a “passive-aggressive way.” Wallace also agreed that Dillard was a victim of racial discrimination.

There is little question that the most powerful chapters in the book are the final four. In these final pages Wallace’s voice in all its thoughtfulness, sadness and anger, command the reader’s attention. … For the first time Wallace reveals, in his own words, “less of the good, quiet, obedient, Negro.”

Also troubling is Maraniss’s characterization of Chancellor Heard as being more progressive than he truly was. Maraniss gives him too much credit for diversity. Chancellor Heard cared more about his “reputation as the rare administrator who maintained a peaceful campus” in the volatile 1960s. Wallace did more for diversity on the court and in helping to recruit “Vanderbilt’s first black football players and the next black basketball player to follow him, Bill Ligon.”

There is little question that the most powerful chapters in the book are the final four. In these final pages Wallace’s voice in all its thoughtfulness, sadness and anger, command the reader’s attention. In these chapters Wallace publicly reveals his pioneering experience at Vanderbilt—he controls the final narrative of his four years at Vanderbilt. For the first time Wallace reveals, in his own words, “less of the good, quiet, obedient, Negro.” The usually stoic Wallace tells the world that things were horrible dealing with racist teachers, fans, and students.

Coaches, alums, and administrators were shocked that he felt, despite respect for his basketball skills, “ they still considered [him] a person who sweeps floors.” He called his four years at Vanderbilt a “four year tour of duty through a hostile South.” The whites wanted a feel-good story. The good thing about the way Maraniss writes the book is that he shows Wallace quietly swallowing the bile of racism for four years, but when Wallace finally reveals the truth of his trauma the reader does not feel he is bitter. Maraniss strategically made Wallace an empathetic figure since the beginning of the book.

In Strong Inside, Perry Wallace shows that heroic barrier-breaking efforts can make change. The SEC has benefitted more than any other league from integration—the very institutions most hostile to Wallace have capitalized the most.[2] Nonetheless, Wallace’s return to Vanderbilt to be honored, like Williams’s return to Indian Wells, is an unsettling reminder that the rules for the abused need to be rewritten: No longer should the victims be asked to show guts and display honesty, honor, and integrity. Conciliatory expectations of the victims leaves this reader wondering if a day will soon come that the victims of racism-induced traumas will not be burdened with the need to express forgiveness and forbearance. The Perry Wallace story bears this out very well. Strong Inside is a robust tale of a man who rises above negative circumstances and refuses to let people make him hate.