On policing:

1. The wars on drugs and terrorism militarized our police: The sights of police officers mounted atop assault vehicles and dressed in equipment better suited to the military field of battle may seem new. Not quite. They have actually been in storage for quite some time, funded and accumulated over the course of almost 25 years, mostly in response to the “War on Drugs,” followed by alarm at the possibility of domestic terror attacks after 9/11.

The National Defense Authorization Act of 1990 legislated transfers of military-grade weapons and supplies from the U.S. Department of Defense to combat the drug trade. In 2002, the Department of Homeland Security authorized distribution of military-grade equipment to state and local police forces worth $35 billion in grants.

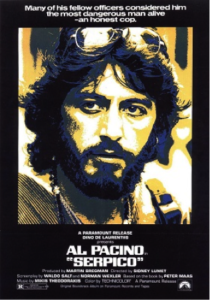

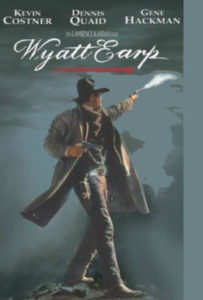

2. The police profession fascinates us more than nearly any other: In the forty-six years between 1968 and 2015, Hollywood films that have  police hero or law enforcement as a central theme have been represented on the top twenty highest-grossing-movies list in thirty-two of those years, a remarkable occurrence for a particular occupation. (Included in this list are westerns where

police hero or law enforcement as a central theme have been represented on the top twenty highest-grossing-movies list in thirty-two of those years, a remarkable occurrence for a particular occupation. (Included in this list are westerns where  a central character is connected with law enforcement such as John Wayne’s character in True Grit, released in 1969.) Dirty Harry (1971) starring Clint Eastwood was a top-ten grosser in the year of its release and so were three of the four Dirty Harry sequels. So were the first three Die Hard films, Lethal Weapon and all of its sequels, Seven, Speed, Witness, Police Academy, and Minority Report. The range of highly successful films about cops is more extensive than one might imagine, from science fiction to broad comedy to gritty urban realism. Eddie Murphy’s Beverly Hills Cop and its sequel were the highest grossing films of 1984 and 1987 respectively, a sign that the public was willing to accept and even like a smart-mouth African American as a police officer, fantasy though it may have been to many. Charles Burnett’s The Glass Shield (1994), about racism and sexism in a big city police department, received mixed reviews and did not do well at the box office. The top-grossing cop films constitute only a very tiny tip of the iceberg of the number of critically acclaimed and commercially successful police films that have been released since 1968.

a central character is connected with law enforcement such as John Wayne’s character in True Grit, released in 1969.) Dirty Harry (1971) starring Clint Eastwood was a top-ten grosser in the year of its release and so were three of the four Dirty Harry sequels. So were the first three Die Hard films, Lethal Weapon and all of its sequels, Seven, Speed, Witness, Police Academy, and Minority Report. The range of highly successful films about cops is more extensive than one might imagine, from science fiction to broad comedy to gritty urban realism. Eddie Murphy’s Beverly Hills Cop and its sequel were the highest grossing films of 1984 and 1987 respectively, a sign that the public was willing to accept and even like a smart-mouth African American as a police officer, fantasy though it may have been to many. Charles Burnett’s The Glass Shield (1994), about racism and sexism in a big city police department, received mixed reviews and did not do well at the box office. The top-grossing cop films constitute only a very tiny tip of the iceberg of the number of critically acclaimed and commercially successful police films that have been released since 1968.

3. Police training, and pay, may matter: The United States’ unique history of racism, violent settlement, and proliferation of firearms plays a sizable role in recent tensions between minority communities and law enforcement. Our nation’s patchwork of police municipalities even developed along historic lines that some would say resonate today. Northern law enforcement agencies were first established as volunteer-staffed “watch” systems of constables, such as those established in 1700 Philadelphia and 1658 New York, while Southern states’ police departments had their origin in “slave patrols” or what the slaves called “paterollers,” such as those created by the Carolina colonies in 1704, with purposes of monitoring slaves’ behaviors and otherwise returning and punishing escaped slaves.

But there is a growing consensus that other nations document far lower rates of deadly confrontation between citizens and law enforcement officers, in part, because these nations train and treat their police officers in ways that differ and depart significantly from United States, both in terms of pay and officers’ relationship to firearms. “Bobbies” in the UK call on guns only when absolutely needed, in the form of armed response teams. Canadian law enforcement officers are often paid in the six figures, with training in communication and empathy skills considered far more important and effective to good law enforcement, allowing them to dominate and control situations without resorting to guns.

But these comparisons must be taken in context; for in a country like the United States which has nearly 300 million guns in circulation, and where the private ownership of a weapon is considered an explicit constitutional right, and where the state does not possess the right to confiscate legally-owned guns, none of which is the case in either Britain or Canada, it would be foolhardy to have a police force that is not armed. Despite a spike in the early 1990s, homicide rates in the United States have been decreasing since the 1980s. But despite the decrease, the violent crime rate remains high in the United States. There were 375 violent crimes committed per 100,000 people in the United States in 2014, 4.5 murders per 100,000. As of 2013, the United Kingdom had a a murder rate of 1 per 100,000 and Canada 1.4. A person is four times more likely to be murdered in the United States than in the United Kingdom. (There are disputes about the crime rate in the United Kingdom.)

Germany trains its officers no less than 130 weeks under a central organization and uniform requirements, with classes in law, ethics, and navigating foreign cultures and communities, such as Muslim immigrants.

Most U.S. police departments, meanwhile, divided across some 18,000 different municipalities and departments nationwide, train recruits for an average of 19 weeks. Whether these differences correlate in measuring the effectiveness of law enforcement in Germany and the United States, without taking into account the different sizes of the two countries, the relative diversity of their populations, the stark differences in the political and cultural traditions and history, is nearly impossible to say. To be sure, what can be said definitively is that policing in the United States has very strong historical roots in slavery and the need for Whites to control African Americans as well as frontier justice and frontier violence.

4. Police bias is real, but not what you might expect: Raw data from a July 11 study this year by Harvard University economics professor Roland G. Fryer Jr. suggests that Hispanics and African Americans are often more than 50 percent more likely to experience non-lethal police force than Whites.

Controlling for differences such as age and type of incident, however, the same study of 1,332 police shootings between 2000 and 2015 in 10 major police departments in California, Florida, and Texas suggests African Americans were 17.3 percent more likely to experience use of police force.

To Fryer’s surprise, however, his study revealed no difference in how White and Black civilians were treated by police in shooting incidents. In data from the city of Houston, he even found that Blacks were less likely to be shot by police, fatally or non-fatally, than Whites. Still, Fryer has said that the disproportionate use of non-lethal force on minority citizens has its own unique and deleterious effects, leading minority citizens to wider distrust of society that can impact educational and employment opportunities.

5. Two authors who made police “realism” popular: Joseph Wambaugh, a former Los Angeles

5. Two authors who made police “realism” popular: Joseph Wambaugh, a former Los Angeles  policeman, is, without question, the most popular and successful police writer of both fiction and nonfiction. His novels have been translated into films and television programs including The New Centurions (1971, also a film), The Onion Field (1973, also a film), The Blue Knight (1973, also a TV film and TV series), The Choirboys (1975, also a film), and The Black Marble (1977, also a film).

policeman, is, without question, the most popular and successful police writer of both fiction and nonfiction. His novels have been translated into films and television programs including The New Centurions (1971, also a film), The Onion Field (1973, also a film), The Blue Knight (1973, also a TV film and TV series), The Choirboys (1975, also a film), and The Black Marble (1977, also a film).

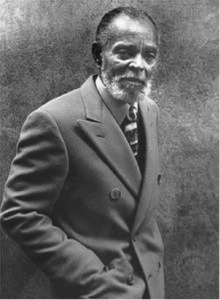

On the other side of the ledger is Black crime writer Chester Himes (1909-1984) whose Black detectives Gravedigger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson, the two most significant and popular fictional Black cops ever created, were featured in such novels as Cotton Comes to Harlem (1965, also a 1970 film), All Shot Up (1960), The Heat’s On (1961), The Crazy Kill (1959), and The Real Cool Killers (1959).

![GetChristieLove.jpg[1]](https://commonreader.wustl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/GetChristieLove.jpg1_-230x300.png) 6. Some famous fictional policewomen: Some of the most famous policewomen have been characters on television series including Teresa Graves as Christie Love in the 1974

6. Some famous fictional policewomen: Some of the most famous policewomen have been characters on television series including Teresa Graves as Christie Love in the 1974  television show, Get Christie Love, one of the earliest dramatic shows to feature an African American female as the lead; Angie Dickinson as Pepper Anderson in Police Woman (1974-1978); Betty Thomas as Lucy Bates in Hill Street Blues (1981-1987); Tyne Daly and Sharon Gless in Cagney and Lacey (1982-1988); and Helen Mirren as Jane Tennison in the British television show Prime Suspect (1991-2006), remade as an American television series (2011-2012).

television show, Get Christie Love, one of the earliest dramatic shows to feature an African American female as the lead; Angie Dickinson as Pepper Anderson in Police Woman (1974-1978); Betty Thomas as Lucy Bates in Hill Street Blues (1981-1987); Tyne Daly and Sharon Gless in Cagney and Lacey (1982-1988); and Helen Mirren as Jane Tennison in the British television show Prime Suspect (1991-2006), remade as an American television series (2011-2012).

7. The police connection to urban unrest in the 1960s: Nearly every major urban riot or race rebellion that occurred in the 1960s, except the violence that resulted from the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968, was the result of a rumor of police brutality, an incident that was construed by many of the Black citizens of a municipality as police brutality, or an actual case of police brutality. This would include the outbreaks in New York City and Philadelphia in 1964, Watts in 1965, and Newark and Detroit in 1967. The Glenville Riots, which occurred between July 23-27, 1968, in Cleveland during the reign of Black mayor Carl Stokes, the first Black to be elected mayor of a major American city, was started by a gun battle between Black nationalists and the police that resulted in the deaths of three policemen and three of the suspects.

8. No one knows for certain if minority representation in police departments matters: Governing Magazine, courtesy of reporter Mike Maciag, recently conducted an extensive study of city and suburban police departments to discover the extent to which each department reflects the racial demographics of the communities they serve.

Allentown, Pa., Hartford, Conn., and Stockton, Calif., ranked as the top-three cities with the least representational police departments. McAllen, Texas; Honolulu, Hawaii; and Washington, D.C. ranked as the top-three cities with the most representational police departments. The million-dollar question of whether or not “closer demographic alignment” between police departments and communities results in better relations and fewer incidents of police brutality, though, remains unanswered.

“As Maciag points out,” a Brookings Institute write-up of the study says, “three of the six Baltimore police officers charged in Freddie Gray’s death were black.”

9. The police are often the subject of ridicule: Contrary to what some may believe, the representation of the police in popular culture has not infrequently been critical, satirical, even disrespectful. From the Keystone Kops to the Police Academy films, from Inspector Clouseau to Officer Dibble in the animated TV series Top Cat (1961-1962), the police have been portrayed as ineffective, foolish, laughable, and bumbling. The police are shown as being ineffective in nearly all fiction and films where they are paired with a private or amateur detective who is the star of the show. Police are usually ineffective in most film noirs because the framed heroes in these films must extricate themselves.

The police have had an ongoing contretemps with rap and hip-hop music artists who have frequently depicted law enforcement in a highly unfavorable light, sometimes encouraging their audiences to defy or even kill the police. This controversy reached its first crescendo with Ice-T’s 1992 song, “Cop Killer.” Ironically, Ice-T has made his living as an actor mostly playing policeman, starting with his role in the 1991 film New Jack City. (Before the rise of rap and hip-hop, Black music was not noted for expressing anti-police sentiments despite the great tension that generally existed in most American cities between minority communities and the police. The first Black political organization to mobilize around the community’s hostility to police was the Black Panther Party started by Huey Newton in Oakland, California, in 1966. Its sole objective was to challenge police authority in the community. One of the ways it did this was through ridicule. It was the Black Panthers who began calling the police pigs.)

On Black Lives Matter:

10. It was one of the first social movements to originate on social media: #BlackLivesMatter started as a hashtag penned by Oakland resident Alicia Garza on social media in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the killing of Trayvon Martin. Black Lives Matter, as a movement, was launched by several members of the African-American gay community.

11. Black Lives Matter is worldwide: There are established chapters of #BlackLivesMatter in Canada, South Africa, and Ghana. After the recent deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, #BlackLivesMatter demonstrations were held in London, Berlin, and Amsterdam.

12. The movement is not concerned exclusively about police brutality: It also advocates on behalf of African-American communities for better public schools, and protests a system that it sees as “funneling” Black youth from “school to prison.” It has also spoken out about better access to health care, child daycare, and women’s reproductive rights.

13. What is more important; Black-on-Black crime or police brutality? Doubtless, the most controversial aspect of BLM is its laser-like focus on police brutality cases. Even some African Americans have been critical of BLM for ignoring the deaths of Blacks at the hands of other Blacks. A Black person is far more likely to be murdered, if he or she is subject to that crime, by another Black than by a police officer, Black or White. Ninety percent of Blacks who are murdered are murdered by other Blacks and Blacks commit half the homicides in the United States. But young Black men are far more likely to be killed by the police than young White men. BLM advocates argue that Black-on-Black homicide and police racial brutality are two separate issues and that those who bring up Black homicide rates are merely trying to divert attention from and downplay the violence visited upon Blacks by the police and that police violence contributes significantly to the overall atmosphere of violence in urban Black communities. The other side of the argument is that BLM is actually devaluing Black lives by saying that the only ones that really count and are worthy of protest are those killed by Whites, that this is, in fact, a perverse of racism as it suggests that only the violence that Whites commit matters and that the violence that Blacks commit does not matter. This controversy over intraracial versus interracial violence and brutality is far from a new or recent debate among African Americans, who strongly feel that they live in a society that does not value their lives or prioritize their safety.

14. BLM and its conservative critics: As of this article’s publication in July 2016, the best-selling nonfiction book about policing on Amazon is The War on Cops: How the New Attack on Law and Order Makes Everyone Less Safe by Manhattan Institute John M. Olin Fellow Heather Mac Donald. The work is, among other things, a thoroughgoing attack on the BLM which Mac Donald characterizes as “fraudulent.” Mac Donald is one of the formulators of the “Ferguson Effect” theory, that there has been a resurgence of violent crime since the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014 because the police have been politically and socially intimidated in doing their work. Naturally, in any dispute as highly fraught politically as this, Mac Donald has her critics. Not all conservatives oppose BLM; some actually have some sympathy for its aims.

15. Whatever your opinion of Black Lives Matter, it has already made history: Time magazine put #BlackLivesMatter on the shortlist at No. 4 for “Person of the Year” in 2015, likening it to a new civil rights movement. Its founders have also been lauded by Fortune magazine as having “succeeded where Occupy Wall Street failed.”