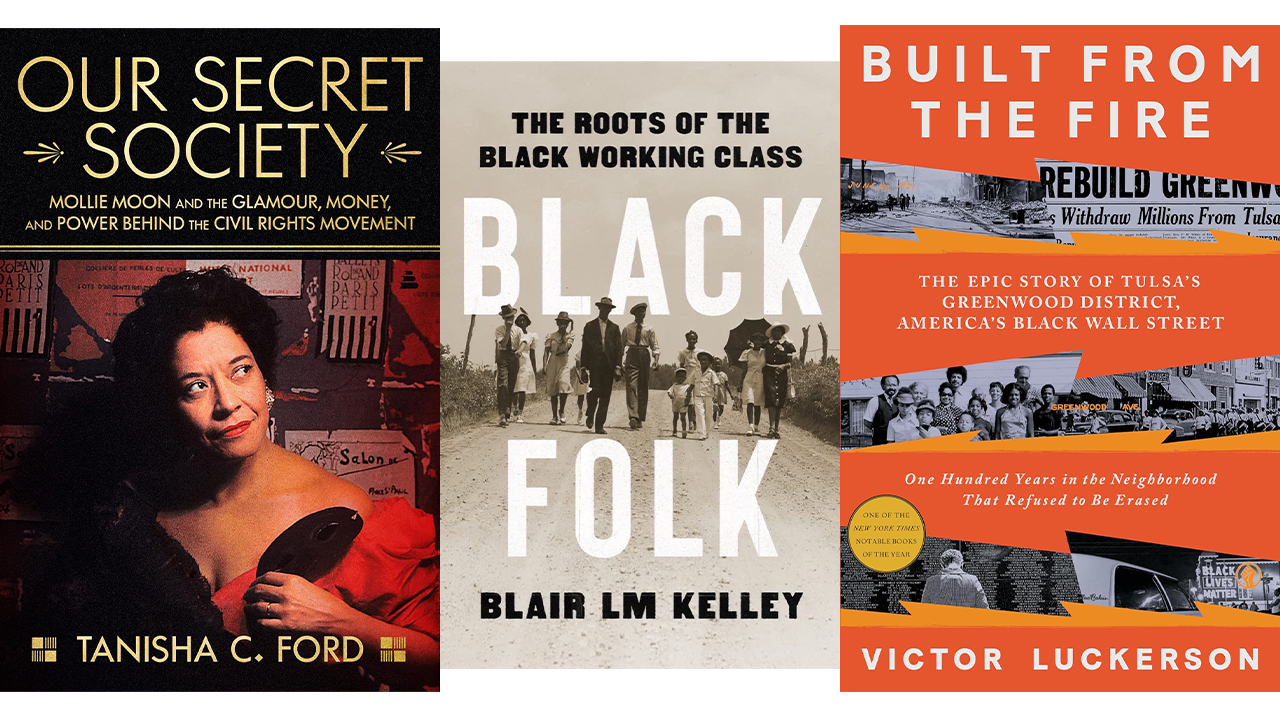

• Tanisha C. Ford, Our Secret Society: Mollie Moon and the Glamour, Money, and Power Behind the Civil Rights Movement (New York: Amistad, 2023) 368 pages

• Blair LM Kelley, Black Folk: The Roots of the Working Class (New York: Liveright, 2023) pages 352

• Victor Luckerson, Built from the Fire: The Epic Story of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, America’s Black Wall Street: One Hundred Years in the Neighborhood That Refused to Be Erased (New York: Random House Books, 2023) 672 pages

Three rich and engaging histories have stepped into the literary landscape and ask us to consider how class status webbed by gender, racism, and urbanization has proven to be such an ongoing struggle as seen through the lenses of Black America. Tanisha C. Ford’s Our Secret Society: Mollie Moon and the Glamour, Money, and Power Behind The Civil Rights Movement, Blair LM Kelley’s Black Folk: The Roots of the Working Class, and Victor Luckerson’s Built from the Fire: The Epic Story of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, America’s Black Wall Street: One Hundred Years in the Neighborhood That Refused to Be Erased ask us to consider what class means in describing the past and the present.

Americans’ relationship to social class and status is as muddled as the American dream. Just what is class? Just what does class mean regarding aspirations, ethnic identity, education, freedoms, gender, neighborhood, occupation, race, religion, and region? What we know is that most Americans believe themselves to be middle-class even if their median household incomes do not meet the economic thresholds for their respective states. In these cases, class is defined using cultural markers and sociological factors such as marriage, religious affiliation, and the status of an employer. Class in the United States is equal parts aspiration, income, and occupation.

Historically, we know that the idea of class was raced throughout the Americas. In 1676, Virginia, the British colony began ranking class by race through a legal explication which has had remarkable staying power. In the colony unfree laborers, indentured and the enslaved, ended up in a messy rebellion known as Bacon’s Rebellion. The rebellion was a hypocritical land grab by a privileged Englishman against indigenous communities. The reason laborers joined the rebellion was they saw an opportunity to end their exploitation from tobacco’s back-breaking work regime.

Like so many peasant and slave rebellions over the centuries, this one failed. It, however, put the fear of God in the large agriculture landowners because the coalescing of the indentured and the enslaved—the Bakongo, Fante, Irish, Igbo, Ibibio, Scots, Welsh, and Yoruba—joined in rebellion together to overthrow the punishing labor regime. This insurgency kept the agricultural elite in a cold sweat. They and the British Crown shared horrid nightmares of their profitable investments being confiscated and divided among laborers. In the aftermath of the insurrection, the colonial court ruled that laborers were to be defined by race. African ethnics would be marked permanently as the lowest laborers, slaves. Their black skin or mixed-race heritage both identified them and defined their status as enslaved. Moreover, this legal definition was gendered. Matrilineally, if one’s mother were enslaved so were her children. On the other hand, British ethnics—Irish, Scots, and Welsh—were quasi “free” at least from lifetime servitude but not exploitation. They were ruled “white.” Though enslaved and indentured laborers shared similar fates as exploited laborers, this legal precedent followed everyone including their mutual and different descendants well into the twenty-first century. This seventeenth-century legal precedent was not exceptional as is popularly overstated. Historically the Dutch, French, Portuguese, and Spanish, all British imperial rivals, enshrined racist hierarchy into law to attain a monopoly on unfree labor as early as the fifteenth century. Class, gender, and race were never inseparable.

What I so appreciate about Kelley’s rendering of the working-class nature of Black life is the compelling beauty of its narrative. She writes of a dignified past to the historically misinformed era whose history is found on sloganeering T-shirts and the mouths of rappers.

Black folk recognized the disadvantages that stigmatized them. They accepted the difficulties of their post-emancipation adventure and recognized the Jubilee that the ending of slavery had brought them. They could exercise more choices about their communities and personhood with the end of slavery. Those terms were never idyllic. Black folk, as Blair Kelley beautifully surmises, used their labor—the sweat of their brows with dirt under their fingernails and washboard callous hands—to build their communities. They marketed acquired skills, bought land, built churches, sharecropped, and took in wash. Like agrarian people everywhere they used every part available of the hog to make their lives meaningful. What I so appreciate about Kelley’s rendering of the working-class nature of Black life is the compelling beauty of its narrative. She writes of a dignified past to the historically misinformed era whose history is found on sloganeering T-shirts and the mouths of rappers. Black folk in past eras always recognized the racial resentment their Northern and Southern White neighbors harbored and violently exercised against them. They were never naïve about the limits of freedom and the aftermath of the civil war. It was no bed of roses, as economist Gerald Jaynes, author of Branches Without Roots: The Genesis of the Black Working Class in the American South, 1862-1882 (1986), and historian Kidada Williams, author of I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction (2023), so vividly show in their books. Nevertheless, they persevered. Perseverance is not a perfect solution to injustices, but self-preservation is an important beginning. They fought using the fortitude learned inside slave communities. They understood the South was dependent on their demographic numbers. The South was equal parts Black as it was White. And this is what made Black people so dangerous throughout the region, they could possibly outvote the White elite.

What Kelley also does exquisitely is weave the lives of Black working-class women into her narrative. Black women are vital parts of other histories: Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Present (1985) and Joe Trotter Jr, Workers on Arrival: Black Labor in the Making of America (2019). What makes this history rich is the extensive research and endearing personal quality of Kelley’s prose. She is narrating members of her own family’s journey. Black women were key to the economics of every Black community and Kelley, with the greatest of tenderness, shows what this meant for the men, children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews they reared.

These women attempted “to hold back a tide with a broom” in the face of deficient federal and state governmental policies from public housing, and education to income assistance. They organized churches, chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids. They tried and continue to try to the best of their abilities to keep the next generation from descending to the various hells of Dante. They worked feverishly like Lutie, the female protagonist, in Ann Petry’s 1946 novel The Street, to keep the babies safe. There was no space where women did not complement their male counterparts in forming a Black working-class culture.

Perseverance is not a perfect solution to injustices, but self-preservation is an important beginning. They fought using the fortitude learned inside slave communities.

The main deficiency of Kelley’s book is that it does not define what class aspiration means for Black folk. The respectable working class has never wanted their children to be solely categorized as workers or essential laborers. “All work has dignity” as Dr. King told Memphis Sanitation laborers in 1968, which is true. However, all the sanitation workers wanted their daughters and sons to attend Fisk University, Lemoyne College, Tennessee State, or a good trade school. How did Black people define class aspirations and what does that tell us about the ends of working-class culture, especially a culture so profoundly infused by forms of Black Protestantism? Professor Kelley is her own case in point. Though she has working-class roots, she is nevertheless a highly esteemed academician and author at the apex of university life. While Black folk are the working class, they never wanted their children to remain stuck in the injuries, moroseness, and traumas that accompany working-class life.

My other thought regarding Kelley is the underground economy that all African Americans participated in either by choice, force, or necessity. Black working-class communities have often resembled the hustling life of Bertolt Brecht’s 1928 Three Penney Opera. And as Kelley concludes not everyone makes it through the perils of Black working class life. Here, however, she might have consulted historian LaShawn Harris’s Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy (2016), which today is supported by the rich memoirs such as journalist Bridgett M Davis, The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in Detroit Numbers (2019) and Donovan Ramsey’s, When Crack Was King: A People’s History of a Misunderstood Era (2023). On one end we have Davis being supported through Spelman College via the income her mother’s numbers operation provided. And on the other, the structural end as Donovan Ramsey testifies slinging was a perilous way to climb out of the deindustrialized ’hood of the crack era. Even with these criticisms, Kelley has written a tour de force. And now we can turn the page to Victor Luckerson’s marvelous book.

The Tulsa massacre was a horrible pogrom in an era of heinous violence aimed at destroying Black communities’ accumulated wealth, labor, and political clout. From Thibodaux, Louisiana, to Wilmington, North Carolina, to Tulsa the brutality in attempts to keep Black people politically and socially subordinate was ruthless. However, Luckerson reminds us that folks were aspirational. Like Exodusters fleeing for Nicodemus, Kansas in 1877 and the “freedom-seekers” who built the 1854 all-Black town of Quindaro, Kansas, folks arrived in Tulsa riding the wave of Oklahoma’s boom economy with the discovery of crude oil in 1859. “Indian Territory,” as Oklahoma was called in the aftermath of the “trail of tears,” the mass removal of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole along with those they enslaved from the southeast quadrant of the United States and the displace Wahzhazhe (Osage) from Kansas. For thirty-plus years, beginning in 1882, synchronized racist laws passed by Congress permitted the Chinese Exclusion Act, the legal dispossession of indigenous peoples’ lands and mineral rights, and state segregationist legalities throughout the South. Through all the intersectional legislative machinations that were used to disinherit, Luckerson carefully charts the rise and the staying power of Tulsa’s Greenwood community.

He begins with the aspirational journeys of an emerging middle class who left states like Mississippi and elsewhere in search of opportunity. He reminds us that before “the Great Migration” Black people were steadily moving to the lower parts of the Midwest and as far west as Kansas and Oklahoma. These aspirational men and women drank up Booker T. Washington’s idea of self-sufficiency through business ownership like moonshine at the end of harvest. They hosted Washington’s National Negro Business League (NNBL) proudly and the Wizard of Tuskegee did not fail them. Washington boosted the aspirations of men and women who wished to be leading lights of their city.

Through all the intersectional legislative machinations that were used to disinherit, Luckerson carefully charts the rise and the staying power of Tulsa’s Greenwood community.

These driven men and women motivated by the Gospel of entrepreneurship creatively figured out how to finance churches, confectionary shops, general stores, hotels, law offices, taverns, office buildings, and a movie theater and newspaper. And as word spread through intentional promotion others came to join them, some with means and many others without. Greenwood was such a success its moniker became “Black Wall Street,” though the overwhelming number of its constituents were working-class living in substandard rentals. Nevertheless, the people of Greenwood were proud of what they individually and collectively had accomplished. And many of them believed in a better future.

In 1919, racist tornadoes swirled across the United States known as the Red Summer. The most epic were in Helena, Arkansas, Chicago, and Omaha. It would not be long before the political virulence would reach Tulsa’s Greenwood. Everywhere White America felt threatened by the new assertiveness of Black communities, especially men who had served in the Great War. Greenwood had all the attending signs of a pogrom in the making. Its male veterans, its economic success, and its sense of community solidarity. Greenwood’s success, however fragile it was, seeded the long underlying resentment that both the White middle class and its working class harbored. Fomented by the resurgence of the Klu Klux Klan’s virulent White nationalism there could be no competition by Black people as members of a racialized class. The cry of rape that repeatedly set off a five-alarm fire alarm signaled the end of Greenwood’s fragile success. Forced or unforced interracial sex was the trigger for blood to be spilled. And the horror, like what occurred among the Osage nation, was that land would be seized and stolen in the aftermath of Greenwood’s destruction, a disinheritance that still lives with Tulsa to this day.

And this is a credit to Luckerson’s skill as a history writer: he does not end Greenwood’s story in 1921. Rather he shows how the folk of Greenwood, though traumatized like concentration camp victims, valiantly put their neighborhood back together. They persevered. However, they rebuilt via family relationships, usurious bank financing, back-alley gambling, pool halls, and whatever above-ground and underground economic opportunities they could seize. World War Two once again called the daughters and sons of Greenwood to serve their country. They, like the rest of Black America, fought the Double V campaign, victory over fascism abroad, and victory over racism at home. Nazi racism was nothing but an extension of what they had been fighting in U.S. society. The end of World War Two had many of the problems that marked the end of the First World War. Harassment of Black veterans, fights over housing and employment, but this time around there was greater militancy, and thanks to the legal efforts of the NAACP more legal victories to support Greenwood’s efforts in building their community in their own image.

It was the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, that gave license to reckless suburbanization that gutted ethnic working-class communities of every stripe and irrevocably harmed Black communal solidarity dividing neighborhoods around the country to such an extent that one can barely remember that there once had been intact communities with institutions that glued people together in common cause and democratic disagreement. In Greenwood, the highways divided a once intact neighborhood filled with people. There was no longer walking six blocks to church. It was crossing the overpass. The professional middle class in search of better creature comforts moved and were in less contact with the working class than they had been. Only the limited bonds of the church in the old neighborhood brought them together, but not the diner, the schools, stores, entertainment venues, or old amusement parks. Intraclass interaction became far more tenuous. And, yet, as Luckerson shows, the people of Greenwood recognized the importance of what they had built and continue to build. They desired striving, intact Black communities in the same manner as those who arrived in Greenwood one hundred thirty years ago.

… this is a credit to Luckerson’s skill as a history writer: he does not end Greenwood’s story in 1921. Rather he shows how the folk of Greenwood, though traumatized like concentration camp victims, valiantly put their neighborhood back together. They persevered.

This brings me to Tanisha Ford’s richly written biography of Mollie Moon. Ford, in the historian profession, has been an original scholar investigating the importance of women’s dress in the civil rights struggles and beyond, as well as the photography and cultural politics of Kwame Brathwaite who coined the phrase “Black is Beautiful.” She now turns her intellectual gaze to a little-known but certainly most notable activist, Mollie Moon, whose cultural galas became a major fundraiser for the civil rights movement, benefitting the National Urban League and major leaders of protest such a Martin Luther King Jr. Ford’s biography helps us to understand the importance of New York City in the civil rights movement. She adds a more vivid and personal sense to Martha Biondi’s 2006 book To Stand and Fight: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Postwar New York City. Ford shows us the “ in crowd” through Moon’s life and activism.

Moon had an arduous journey in an era when few Black people barely made it through eighth grade. Cleveland, where she was reared as Mollie Lewis, was a challenging city populated with working-class ethnics from Central and Eastern Europe—then Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Ukraine—and Black working-class migrants from the South, especially Alabama. Cleveland was a city rife with working-class insecurities fueling jealousies and racism. Working-class people were fractured. Nevertheless, it was a city where Black people were able to create significant communities and offered someone like Langston Hughes, who graduated from a Cleveland high school, an opportunity to try out many of his plays in the city. There Moon gained a strong high school education and interacted with peers who loved the stage and found solace and youthful idealism in conversations on political economy and socialism. Graduating from high school as the Great Depression blew across the United States was enough incentive to critically examine capitalism. Her deep interest in social class would follow her all her life. Because she had such a strong education she was able to make her way to New York’s Columbia Teachers College.

Ford’s biography of Mollie Moon helps us to understand the importance of New York City in the civil rights movement. … Ford shows us the “ in crowd” through Moon’s life and activism.

Moon’s education enabled her to move in a circle of emerging well-educated Black women from Dorothy West to Louise Thompson. As an adventurous young woman Moon joined them on an excursion to the then Soviet Union to assist in making Black and White, a project that never saw the light of day. The film received its greatest notoriety from Langston Hughes’s 1954 memoir I Wonder As I Wander. When Joseph Stalin canceled the film, the group fell into recrimination, including Moon’s future husband Henry Lee Moon who departed the Soviet Union in a huff. Like Hughes, Mollie decided to take her pay and travel. She headed to Germany; a decidedly bold move in 1932 as the Weimar Republic was on the verge of collapse. The time she spent in Germany was enriching. It gave her a more cosmopolitan perspective on the world and complicated her thinking about social class in the United States. However, the rise of Hitler’s Nazi Party would force her to take leave and return to the United States.

Moon returned home and found herself doing what women have done over the centuries: she married. In Moon’s case, she married twice, and both failed. And in the circles she kept, among the small and insular middle class in New York and Washington, D.C., failed marriages fed the rumor mill. However, she and Henry Lee Moon married in 1938, when she was thirty-one and he was thirty-seven, despite the naysayers. For the first years of their marriage, they commuted between New York and Washington. The Moons, in Ford’s words, became a power couple among their peers. Henry Lee Moon worked at the lower level of the Roosevelt administration and Mollie Moon as a social worker in Manhattan. Though the couple lived relatively well in comparison to the Depression-era and World War Two Black America, they were not in the empirical upper middle class. And here, I wish Ford would have described in just a little more detail the state of Black middle-class marriages economically. While the Moons had escaped the harshness of working-class life, they had not escaped the fragility of what it meant to be Black and middle-class.

As a couple, they both feared the loss of income. Texas Congressman Martin Dies chaired the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) prompting the Red Scare through the late 1930s and early ’40s. The Moons, who both traveled to Russia, were considered communist sympathizers. Constant surveillance kept the couple fearful. Being brought before HUAC could be ruinous. The small Black middle class—artists, government employees, professionals, and schoolteachers—especially in the South lived being surveilled. The constant scrutiny at both the local, state, and federal levels of government helped them perfect a conservative pose. This is an area that the sociologist E. Franklin Frazier could have highlighted more in his scathing 1957 critique, The Black Bourgeoisie. His emphasis on banal sociality was carried out in response to constant surveillance. The irony of this sociality was this is what permitted Mollie Moon, and many women who preceded her funding churches, clubs, and congregations, to become master fundraisers.

Institutionally, Mollie Moon would eventually lose the battle to keep the guilds independent of male leadership. However, before her departure, the civil rights movement benefitted from her wide network of donors and friends. No movement can succeed without its entire community being activated.

Ford wonderfully charts Moon’s rise as a masterful party organizer. Simply put, everyone wanted to attend an event Mollie threw. These costume balls, galas, and dinners were organized to crack social inequities. They were network events for artists, activists, the aspiring and corporate leaders, initially on behalf of Harlem, but which grew to a national scale.

However, with successes come jealousies. Moon’s success in building a cadre of women for the National Urban League to raise money around the country became feared as women asserted more independence from male leaders. Like Black male clergy, Lester Granger and Whitney Young, both heads of the National Urban League, were always leery of the accumulated power Moon held through fundraising and networks. The Urban League Guilds, as they were called, challenged male-centric leadership. Institutionally, Moon would eventually lose the battle to keep the guilds independent of male leadership. However, before her departure, the civil rights movement benefitted from her wide network of donors and friends. No movement can succeed without its entire community being activated.

These three rich histories give us the lived experiences of persons negotiating a racialized class system. These new narratives are instructive because Black Americans, despite class being violently raced in the United States, have had robust internal conversations within their own walls about what life as men and women, entrepreneurs, professionals, and essential workers mean in democratic conversation one to another.