There is a bit in the 1990s British television series I’m Alan Partridge where the wonderfully dimwitted television host, played by Steve Coogan, describes Paul McCartney and Wings as the “band the Beatles could have been.”1 The joke, of course, is that Wings have frequently been treated by critics as a band not to be quite taken seriously or, at best, as a sort of prolonged afterward to the work that McCartney had done with the Beatles. McCartney’s initial post-Beatles albums—first as solo act and then with his new band Wings—were viewed not only as a disappointment by many music critics at the time but also as somehow symbolic of a broader cultural letdown. In a memorably hyperbolic review for Rolling Stone, Jon Landau described Ram (1971), the only record credited to Paul and Linda McCartney, as marking “the nadir in the decomposition of Sixties rock thus far. For some, including myself, [Bob Dylan’s] Self-Portrait had been secure in that position, but at least Self-Portrait was an album that you could hate, a record you could feel something over, even if it were nothing but regret. Ram is so incredibly inconsequential and so monumentally irrelevant you can’t even do that with it: it is difficult to concentrate on, let alone dislike or even hate.” Such vitriol towards a pop record is now hard to imagine, but it begins to suggest the nearly impossible situation where Paul McCartney found himself at the start of the 1970s as he began to imagine a post-Beatles future. Of all the Fab Four, it was McCartney who appeared the most conscious of what the burden of being an ex-Beatle would entail—the “Carry That Weight” section of the Abbey Road medley seems keenly prescient of how the Beatles would overshadow whatever work John, Paul, George, and Ringo would produce as individuals. And to the dismay of many music critics, McCartney’s early solo records, with the possible exception of Ram and then Band on the Run (1973), were deliberately low-key affairs, as if he did not want to compete with his Beatle past.2

In refusing to rehash the Beatle story once again, Kozinn and Sinclair ultimately give a much more nuanced, and ultimately compelling portrait of McCartney. Of all the Beatles, Paul was most affected by the breakup, the dissolution shattering his self-image and undermining his artistic confidence.

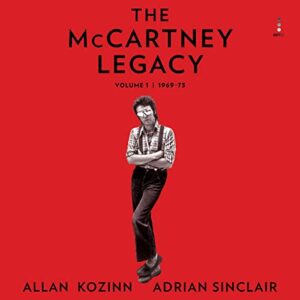

Starting with the homemade sessions that were at the heart of his solo debut McCartney (1970), Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair’s The McCartney Legacy Volume 1 follows the first four years of Paul’s solo career, as he tentatively discovered a way to make music again outside of the boundaries of his old band. Kozinn, a music critic and former culture reporter for the New York Times, and Sinclair, whose background is in television documentaries, prove themselves to be immensely knowledgeable critics and historians, their work illuminating how McCartney went about constructing his music in the wake of the Beatles’ demise. The first of a planned four volume set devoted to McCartney’s post-Beatle life and career—the second installment is tentatively scheduled to be published in 2025 and will cover the end of 1973 to the beginning of 1980—The McCartney Legacy chronicles in astonishing detail the turbulent first few years of Paul’s solo career, endeavoring to treat his post-Fab albums with the same level of care that his work in the Beatles has traditionally received. The book pivots between a detailed history of recording of McCartney’s recording sessions—if you ever wanted to know what songs Glyn Johns produced during the Red Rose Speedway (1973) sessions then this is the book for you—alongside a more traditional biographical narrative. Kozinn and Sinclair offer a few juicy revelations. Not surprisingly, considering what would later happen to them in Japan in 1980, Paul and Linda were not the world’s most clever drug smugglers as they got busted in Gothenburg, Sweden for having “5.8 ounces (0164.6 grams) of poorly concealed hashish” shipped to their hotel under the label of “cassettes,” one of several busts that the McCartneys experienced in the early 1970s. (464) Paul could also be a controlling bandmate and a somewhat disconnected bandleader; both Henry McCullough and Denny Seiwell would leave Wings in 1973 due partially to the relatively low salary that McCartney paid the band.3 Behind the stoned hippie bonhomie of the band’s image, touring in a Magical Mystery-style psychedelic bus for their 1972 Wings over Europe tour, there was tension within the band, especially toward Linda’s (self-admitted) limited musical ability.

… to the dismay of many music critics, McCartney’s early solo records, with the possible exception of Ram and then Band on the Run (1973), were deliberately low-key affairs, as if he did not want to compete with his Beatle past.

The ambition of Kozinn and Sinclair’s project, however, is incredible—and, to this self-confessed Macca nerd, thrilling—as they give a comprehensive history of McCartney’s early solo work. It is at this point in the review that I should probably pause and admit that I have a bit of a McCartney problem. I own multiple copies of most of all his records, including three copies of Ram on vinyl; I have strong opinions as to why the originally planned double album version of Red Rose Speedway is superior to the slimmed down single disc that was eventually released; I have been known to defend lesser Macca records like Press to Play (1986) and Back to the Egg (1979) at dinner parties (probably why I am not invited to many soirees these days); I own a copy of Paul’s tedious 1984 feature film Give My Regards to Broad Street (1984) on VHS; instead of any diplomas, I have a framed cover of McCartney II hanging from my office wall. This is all a way of saying that I am sort of an ideal reader for a book like The McCartney Legacy. Unlike most McCartney biographies, which seem to have little to say about the man’s actual music output, The McCartney Legacy focuses on how Paul went about constructing and recording his work, giving an invaluable history that helps illuminate how he re-conceptualized his art in the wake of the Beatles’ break-up.4 The book offers a clear-eyed assessment of Paul’s first solo records that does not attempt to explain away some of McCartney’s more baffling artistic decisions—the sections detailing his insistence on recording the children’s lullaby “Mary Had a Little Lamb” as Wings’ second single are particularly amusing. “I didn’t understand it,” Wings’ original drummer Denny Seiwell recalled of the decision to release the lullaby as a single. “Henry [McCullough] and I, the two rebels in the band, we said ‘I thought we wanted to become a rock-and-roll band; what the hell is this “Mary Had a Little Lamb’ shit?’” (398) Yet, Kozinn and Sinclair treat the music seriously, capturing McCartney’s propensity to obsess, sometimes to the detriment of the songs, over the smallest details in his music. The book chronicles each of McCartney’s recording sessions, giving a detailed account of his creative process. The McCartney who emerges is both artistically restless—ideas for new projects seem to come from him continually—and uncertain of how to move forward in the aftermath of the Beatles’ unthinkable success.

At over seven hundred pages, Volume 1 captures the dizzying (and exhausting) experience of being Paul McCartney in the early 1970s. The book covers perhaps the most tumultuous, yet productive period of his solo career, as he grappled with how to move forward in the wake of the Beatles’ messy (and prolonged) break-up in 1970, a divorce that put him at painful odds with his former mates. Kozinn and Sinclair meticulously follow Paul through an insanely busy and tumultuous few years: Beatles’ bust-up; retreat to Scotland; lawsuits; Allen Klein; several babies (Mary and Stella); new band (Wings); convincing Linda to join said band; public feud with Lennon; numerous drug busts; more lawsuits; bans from the BBC (for the protest song “Give Ireland Back to the Irish” and celebration of sex and drugs “Hi, Hi, Hi”); ramshackle bus tours; vomiting lead guitarists; being accused of musical appropriation by the Nigerian musician Fela Kuti; surviving armed robbery in the streets of Lagos. The book wisely relies on interviews with Paul and Linda from the 1970s, giving a sense of how painful the Beatle past was for Paul in those first few years after the break-up. “I’ll tell you the truth—it was too painful,” McCartney notes of his decision to not play any Beatle songs on Wings’ initial concert tours (the closest Paul would come to his Beatles past was singing Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally,” which had been a staple of the Fabs’ live act). “It was too much of a trauma. It was like reliving a sort of weird dream, doing a Beatles tune.” (409) Kozinn and Sinclair also suggest how Linda’s encouragement was vital to Paul’s efforts to carry on while also capturing the derision and hostility that her presence as a member of Wings generated from both the music press and her bandmates. The book also features wonderful insight from McCartney’s bandmates and those who worked with him in the studio. Denny Seiwell’s reflections on his time with Wings are especially valuable as they capture the contradictory impulses—a desire to be part of a group on the one hand; a need for artistic control on the other—that informed McCartney’s decision to form a new band instead of surrounding himself with his famous friends, which is the strategy that Harrison and Lennon largely took on their initial solo work. By the end of the volume, McCartney has both enjoyed his most critical and popular success with the release of Band on the Run in 1973 and lost half his band, as both McCullough and Seiwell left Wings on the eve of recording that album.

“To a great degree, [McCartney’s] work and his life are inextricably entwined,” Kozinn writes in the volume’s introduction, “you can enjoy his work without knowing a thing about him, of course; but there is a fascinating story in the way his life and attitudes, the things that please, anger or depress him, the interplay between confidence and insecurity in his psyche, the tension between his desire to collaborate and his need for control, and his way of seeing the artistic possibilities within anything from a newspaper headline to a random postcard all combine to make his work what it is.” (4) This claim at first seems curious as McCartney has always had the knack for crafting songs about the lives of other people—poor Father McKenzie “writing the words of a sermon that no one will hear” or Desmond and Molly “happy ever after in the market place”—but Kozinn and Sinclair make a compelling case for how the events of those years filtered into McCartney’s songwriting, particularly how the hurt inspired by the Beatles’ break-up can be felt in many of Ram’s best tracks. Detailing the sequencing of that album, Kozinn and Sinclair note how “Paul was instantly set on one thing: the LP would start with the ‘Too Many People,’ the McCartneys’ melodic brickbat for John and Yoko, complete with its ‘piss off cake’ backing vocals: and conclude “with Paul’s grand production piece and teen-spirit manifesto, ‘The Back Seat of My Car.’ Not coincidentally, the closing line of the LP, ‘we believe that we can’t be wrong,’ was also directed at the pro-Klein camp.” (251) Indeed, the book reveals Paul’s initial solo records to be deeply personal, reflecting the contrast between McCartney’s tranquil, hippie private life and the resentment and hurt occasioned by the Beatles’ split and his ire over Allen Klein’s control over his artistic and financial future.

By the end of the volume, McCartney has both enjoyed his most critical and popular success with the release of Band on the Run in 1973 and lost half his band, as both McCullough and Seiwell left Wings on the eve of recording that album.

The decision to write a biography of McCartney that starts in 1969, a place where most books on the Beatles end, would also seem to be an odd decision. Even Macca’s authorized biography, the Barry Miles-penned Many Years from Now (1997), pretty much ends in 1970, with McCartney’s solo career and life after the Beatles being covered in a brief afterword. Indeed, Many Years from Now gives more space to Paul’s dalliance with painting and his friendship with William de Kooning than to any of his solo records or his time with Wings. In refusing to rehash the Beatle story once again, Kozinn and Sinclair ultimately give a much more nuanced, and ultimately compelling portrait of McCartney. Of all the Beatles, Paul was most affected by the breakup, the dissolution shattering his self-image and undermining his artistic confidence. “There are lots of people who’ve been through worse things than that but for me this was bad news because I’d always been the kind of guy who could really pull himself together and think, “Oh, fuck it,’ but at that time I felt I’d outlived my usefulness,” McCartney recalled of his reaction to the breakup. “This was the overall feeling: that it was good while I was in the Beatles, I was useful and I could play bass for their songs, I could write songs for them to sing and for me to sing, and we could make records of them. But the minute I wasn’t with the Beatles any more it became really very difficult.” (51)

What’s fascinating about much of McCartney’s immediate post-Beatles output was how self-consciousness and, to some extent, uncertain Paul was about how to go about forging a solo career. The book captures the essential contradiction that shaped McCartney’s early records: his need to be in a band versus the desire for artistic control that made being in a band difficult. The early days of Wings are especially fascinating to revisit as Paul attempted to recreate his early Beatles days by taking Wings on a bus tour of English universities, an idea that he had initially pitched toward the end of the Beatles as a way of rejuvenating the band, a proposal that Lennon had quickly shut down. Ultimately, The McCartney Legacy smartly complicates the conventional narrative of McCartney’s solo work, displaying how he deliberately shaped each record as a response to what had immediately come before it: the pared down McCartney a response to Abbey Road’s studio sparkle, Ram’s crafted studio production a response to McCartney, the quickly cut Wild Life a response to Ram, and so on. The McCartney Legacy, however, is at its best in bringing attention back to some of the forgotten gems in McCartney’s oeuvre—the shimmering bounce of McCartney’s “Hot as Sun,” the ingenuous construction of “Back Seat of My Car,” the harmonies and musical details that grace Red Rose Speedway and Band on the Run. So, find yourself some good headphones, crack open The McCartney Legacy, and, to steal a line from McCartney’s erstwhile bandmate John Lennon “Turn off your mind / Relax and float downstream.”