Decades before Woodward and Bernstein, a reporter made national news for challenging an American President. She was African American, living in the Jim Crow era, who did not enjoy the support of a powerful publisher. She was the “first and only” through much of her career.

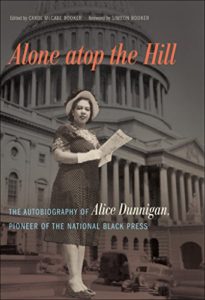

Alice Allison Dunnigan (1906-1983) was never fazed by her unique professional status. She spent her life fighting against racism and sexism, as she recounts in Alone atop the Hill: The Autobiography of Alice Dunnigan, Pioneer of the National Black Press. The title refers both to Russellville, Kentucky cottage, where Dunnigan was born to sharecroppers and to her career on Capitol Hill. Journalist and lawyer Carol McCabe Booker rescued the self-published manuscript from obscurity, edited and retitled it.

Dunnigan changed African-American journalism and, in the process, became an unsung hero of the civil rights moment. Before Dunnigan, black reporters in the nation’s capital relied on back-door reporting, getting their information second hand through African American messengers and servants. They were refused press passes because they did not work for daily newspapers or the wire services. Conditions improved for black journalists during World War II, when it became important to the Roosevelt administration to “sell” the war to blacks and to make sure they were supportive of the war effort. To this end, the administration realized it needed the black press on its side.

Dunnigan demanded and received the credentials that gave white, usually male, reporters access to the White House, Congress and the Supreme Court. Those press passes enabled her to ask tough questions that made President Dwight Eisenhower and other officials squirm. She was not only the first accredited African American White House correspondent, she was the first woman to cover professional sports.

As a little girl, Alice Allison showed perseverance. At the time, rural black school children were encouraged to drop out and go to work. Instead, she trudged miles in deep snow to go to school, so bundled in sweaters, coats and scarves that her schoolmates said she looked like “a very stuffed rag doll.” As a teenager, she furtively entered the ladies’ room at the county courthouse because there was no facility for blacks. “‘The white folks will beat you half to death,’” her mother reprimanded. “From that time throughout the rest of my life, I have worked to break down discrimination,” Dunnigan writes.

“My days had no hourly limit. My work week had no end,” she writes. Yet her paychecks were so small that she routinely had to pawn her watch to eat. She juggled rent money with her son’s college tuition, while struggling to purchase the apparel she needed to look appropriate at Embassy Row Events.

Impressed with her determination, her Sunday school superintendent lent her the money for her college tuition. She prayed for a good job. “Either you make a schoolteacher or you end up in the white folks’ kitchen,” she writes. A teacher died just before the fall semester and she began her first career as teacher-cum-janitor in a one-room school heated by a pot-bellied stove. She was never to feel the same sense of accomplishment and gratitude that she felt with her first teaching until, 30 years later, she walked into her first White House press conference.

While in high school, she began writing a column composed of what she “one-sentence stories” about events in her small community. The newspaper ran similar columns about other small towns. When she wrote a sentence about a car being struck by a freight train, her editor added details from his imagination and ran it on the front page. Dunnigan recounts that she was “thrilled beyond description and vowed that someday I would be a recognized journalist.”

Marriage to her first husband made her realize the only way she would get anywhere would be on her own. Her second husband, “a sporting man,” abandoned her and her only child, Robert William Dunnigan. With her mother taking care of her son, she began teaching at a Julius Rosenwald school in New Hope, Kentucky.[1] Over the summer, she cleaned houses and worked for the Works Progress Administration, where she chided officials for giving white women office jobs while black women were told to salvage food from dumpsters and clean public buildings.

Dunnigan, in the spirit of Carter G. Woodson, developed materials for her students showing how Negroes helped build America, which she sent to an African American newspaper in Louisville. The grateful editor offered her a paying summer job, which led to special training in journalism at what is now Tennessee State University.

A poster in a U.S. Post Office changed her life. The federal government at that time was advertising for clerk typists, in Washington, D.C. Dunnigan embarked for the nation’s capitol, at the age of 36, not knowing a soul there. Claude Barnett, the founder and director of the Associated Negro Press, a news service for 112 black weeklies in the United States, hired her part-time. This helped her keep the wolf from the door.

Five years later, Barnett named Dunnigan chief of the one-person bureau, at less pay than her male predecessor. During her first day on the job, January 1, 1947, she covered a debate in Congress, dubbed “the Do Nothing Congress” by President Harry S. Truman in his re-election bid in 1948. Officials barred her from the press gallery. When she protested, they said she needed a letter of recommendation. “For years, we have been trying to get a man accredited … and not succeeded. What makes you think that you—a woman—can accomplish that feat?” her boss Barnett wrote. Somehow, Dunnigan got the letter. Next, She told President Truman’s press secretary, “The Republican Congress is admitting Negro reporters, when is the Democratic White House going to admit us?’ She quickly won that press pass.

“My days had no hourly limit. My work week had no end,” she writes. Yet her paychecks were so small that she routinely had to pawn her watch to eat. She juggled rent money with her son’s college tuition, while struggling to purchase the apparel she needed to look appropriate at Embassy Row Events. The Truman White House invited her on the June, 1948 election year Whistle Stop Tour, but Barnett said, “Women don’t go on trips like this.” Paying her own way, Dunnigan boarded the train, the first and only black female reporter. She scooped the competition when hundreds of students in Missoula, Montana, lined the tracks late one night to see the President. Truman came out in his pajamas and robe and a student yelled out a question on civil rights. He proclaimed, “Civil rights is as old as the Constitution and as new as the Democratic platform of 1944.” He implied it would be part of the 1948 party platform. A photograph of Dunnigan and Truman shaking hands splashed across the front pages of Negro weeklies throughout the United States.

She lobbied Barnett to attend the 1948 Democratic National Convention. Despite his discouragement, she went. She wrote how Hubert Humphrey’s speech supporting civil rights split the Democratic Party three ways. The Dixiecrats marched out of convention hall and into the States’ Rights Party, which polled 2.5 percent of the popular vote in the election. Henry Wallace, FDR’s vice president from 1940 to 1944, had already formed the extremely liberal Progressive Party, which died ignominiously in November 1948 receiving only 2.4 percent of the popular vote.

No one believed that Truman, who assumed office following the death of Roosevelt in 1944, would be elected in his own right. In an effort to attract the black vote, the Democratic National Committee hired Dunnigan to tour the African American hamlets of Kentucky stumping for Truman. She loved it, buttressed by the fact that Truman’s executive order desegregating the military in the summer of 1948 and the strong civil rights plank in the Democrat Party platform made Truman an easier sell than he might otherwise have been.

After the election, she contended with more racism in Congress, where some legislators heckled and disrespected black reporters, referring to them with racial slurs.

Paying her own way, Dunnigan boarded the train, the first and only black female reporter. She scooped the competition when hundreds of students in Missoula, Montana, lined the tracks late one night to see the President. Truman came out in his pajamas and robe and a student yelled out a question on civil rights. He proclaimed, “Civil rights is as old as the Constitution and as new as the Democratic platform of 1944.” … A photograph of Dunnigan and Truman shaking hands splashed across the front pages of Negro weeklies throughout the United States.

As black athletes were being drafted into the professional leagues, Dunnigan crashed the all-male world of sports reporting. But her heart remained covering stories concerning civil rights and racial progress. Off she went to Fayette County, Tennessee, to report the plight of blacks trying to vote. She covered sit-ins at hamburger stands and “every case involving Negroes that reached the U.S. Supreme Court.”

Again, she wrote Barnett for a recommendation to sit in the high court press gallery. He told her she should ask the Negro court messengers for surreptitious copies of opinions. Instead, Dunnigan blasted black newspaper publishers for tolerating back door reporting instead of standing up for their rights. Covering the highest court proved her toughest assignment; she had to learn the Latin phrases of the profession as well as the complex and crabbed legalese with which many legal briefs are written and translate them into everyday English for her readers.

She followed her idol, 87-year-old civil rights activist Mary Church Terrell, a founder of the NAACP, in desegregating a restaurant. After her death, Dunnigan “pledged to continue the fight she had begun … in the only way I knew how—with the pen.”

While Truman enjoyed working with Dunnigan, Eisenhower did not. Dunnigan asked the newly inaugurated President Eisenhower if he had plans to reactivate President Truman’s Committee on Government Contract Compliance, which mandated equal opportunity jobs for Negroes. He did not answer. At a news conference a year later, she asked about his position on a fair employment practices bill introduced by a Republican senator with enforcement power. Eisenhower snapped back that he had made his position clear: civil rights came from the hearts of men, not from the halls of Congress.

She angered Eisenhower again when she asked about racial discrimination at the Federal Bureau of Engraving & Printing. The Fair Employment Practices Committee had found that the Bureau refused to hire Negro apprentices in defiance of the 1944 G.I. Bill mandating jobs for veterans. Dunnigan asked the President what he planned to do to force the Bureau to hire blacks. Ike was furious because he did not know the answer, even though the issue had been long fought by the federal workers’ union.

An advisor to Eisenhower singled her out of 500 reporters covering the Oval Office, requiring that she give him her reporter’s questions to the President in advance. The same advisor told Dunnigan not to ask civil rights questions, out of fear that any information revealed by her questions would prompt Southern politicians to roadblock President Eisenhower’s legislation in advance. Dunnigan refused, and asked anyway. The President retaliated by snubbing her at his news conferences for three years. Her white colleagues, who respected her work, wrote about her plight. At his first news conference, President John F. Kennedy took his first question from Dunnigan.

During the “New Frontier” of John F. Kennedy’s short and tragic tenure, Dunnigan, now aged 54, began her third career: politics. She was named consultant to President Kennedy’s Commission on Equal Employment Opportunity.

She retired in 1970, and wrote her autobiography, A Black woman’s experience: From schoolhouse to White House. She said, as others like both Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington had posed before, “Judge me not by what I’ve achieved, but by the depths from which I rose.”