Black Films of the 1970s Were Something Else

A review of the guide to all you wanted to know about Blaxploitation films.

December 27, 2022

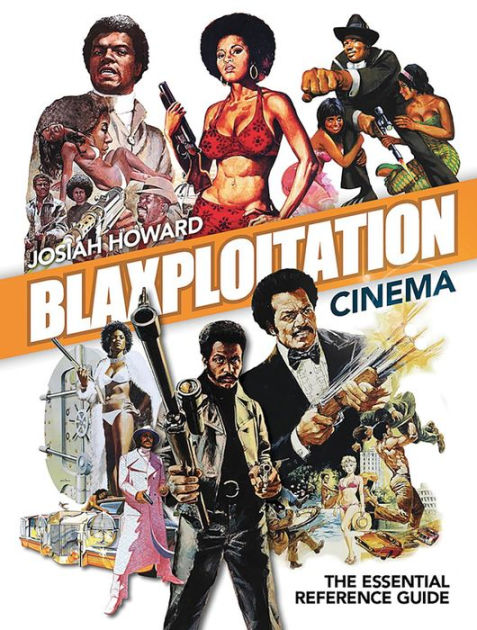

Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide (second edition)

Blaxploitation cinema is experiencing a renaissance. Or, more accurately, it is undergoing a belated restoration. To this end, Josiah Howard’s engaging Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide is invested as much in a discursive reclamation of the loaded term, Blaxploitation, as it is in celebrating the boisterous cinema of the 1970s. The year 2022 marked fifty years since Junius Griffin, then president of the Beverly Hills chapter of the NAACP, introduced the term “Blaxploitation.” Half a century before the likes of Howard used it as a phrase of affection, there was nothing ambiguous, satiric, let alone flattering, about Griffin’s melding of “Black” and “Exploitation.” He meant no compliment to this unprecedented wave of stylish, often garish, cinematic narratives of urban Black antiheros; in fact, he meant war.

In Griffin’s estimation, this wave of action-adventure films, namely Blaxploitation’s holy trinity: the unlikely independent breakout hit story of a sex worker turned political outlaw, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, the slick Black Power meets American noir aestheticism of Shaft and, most pointedly, the glamorous highs and graphic lows of the cocaine trade in Superfly, were “gnawing away at the moral fiber of our [the Black] community.”1 Almost from the moment he issued his reproach, Griffin was flanked by compatriots and contrarians. Indeed, his germinal use of the phrase is so well remembered because it swiftly became a bannering slogan under which a charged debate about the stakes of Black filmic representation was waged. Civil rights organizations staged boycotts, protests, and even proposed a new rating system to protect impressionable Black children from the extravagant images that had them rushing to the theatres.2 Cultural critics wielded the term to warn prospective viewers that the vengeance Blaxploitation (anti)heroes claimed over “the system,” while perhaps alluring, was but a tactless repackaging of racist stereotypes of hyper-virile and violent Black men. Conversely, the phrase was rejected as the pretentious decree of “so-called Black intellectuals,” by filmmakers like Gordon Parks (Shaft), actors like Ron O’Neal (Superfly), and hordes of fans who found the films cathartic and joyous fantasies in which a Black hero finally won, and “the man” finally got his comeuppance.3 In short, the term, Blaxploitation, initially functioned as a loaded conduit to critical debates about the psychological and political implications of Black representation on screen in the waning years of the civil rights era. The refrain did not reflect a considered description of a cinematic genre. Indeed, it was supposed that, like them or not, one knew Blaxploitation when one saw it. The issue was not cinematic demarcation, it was moral repercussion. Under the spectral cloud of its critical origins, the consequences of this assumed aesthetic specificity coupled with definitional ambiguity has come to haunt Blaxploitation’s legacy.

For all the tense debate it spurred, Blaxploitation’s Hollywood reign ended as hastily as it began. In the early 1970s Blaxploitation provided several faltering major Hollywood studios an unanticipated low-cost relief. The “discovery” of Black, mainly urban, audiences, and the relative affordability of producing action-thrillers starring Black casts and directed at Black viewers offered an industry, hobbled by the rise of television and various budgetary missteps, a boon that had been hiding in plain sight. However, by mid-decade, Hollywood began to regain its bearings, and Blaxploitation was shown to be little more than an effective life raft for a failing studio system. The surge of late ’70s Blockbusters like Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) hurriedly rendered the increasingly derivative, and even lower-budget, Black action-thrillers passé. By the onset of the 1980s Blaxploitation was dead, and already fading in public memory.

The term Blaxploitation initially functioned as a loaded conduit to critical debates about the psychological and political implications of Black representation on screen in the waning years of the civil rights era.

Through the 1980s and mid-1990s, when Blaxploitation was conjured it was mostly cited as a brief, somewhat entertaining, but ultimately disreputable blight on Black cinematic history. These early retrospective evaluations were reactionary and failed to consider the films beyond a loaded, and rickety, binary of positive and negative images of Blackness, or racialized conceptions of achievement in filmic aestheticism and production. But pendulums swing, and in the past twenty-five years Blaxploitation has experienced a good-willed revival. The term now evokes a kitschy nostalgia; schlock made hip through the reworkings of postmodernist sardonicism. From Quentin Tarantino’s near-obsessive references in films like Jackie Brown (1997) and Django Unchained (2012), to the lampoonist comedy Black Dynamite (2009), and from contemporary sequels and remakes of Shaft (2000 & 2019) and Superfly (2018), and even to Mr. Potato Head and Isaac Hayes’ crooning adaption of the “Theme from Shaft” to pitch new, crisper fries, Blaxploitation was affirmed as an identifiable and fun cultural signifier. Yet, such homages, and the discourse they reflect and inspire, carry a mild tinge of mockery. They suggest, despite their sincere reverence for the genre, that Blaxploitation was too enjoyably silly to be considered serious or harmful as feverish 1970s critics had warned. Buttressing this parade of popular culture nostalgia were scholarly efforts to reevaluate the cultural significance, aesthetic specificities, and cinematic merits of Blaxploitation. Contributions like avant-garde documentarian Isaac Julien’s BaadAsssss Cinema (2002), studies by foundational Black film scholars Donald Bogle and Ed Guerrero, and more recently, and most deliberately, the advent of Blaxploitation Studies by scholars like Yvonne Sims, Stephane Dunn, Novotny Lawrence, and Gerald R. Butters Jr. have if not always celebrated the films, recognized and framed them as serious works with meaningful, and underappreciated impact. Thus, in our present moment, Blaxploitation’s meaning is found somewhere in a mixture of droll celebration and sober analysis.

Josiah Howard’s Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide merges these two strands of revival. The book is part unabashed celebration of Blaxploitation films and part meaningful assertion of their relative merit. Yet, necessarily set in the echo of its precarious origins, Howard’s effort, through no fault of his own, is always hampered by its contingence on unseating the restrictive and negative associations of the films. Howard is clear on this point. His survey of Blaxploitation is grounded in a “refusal on [his] part to view the term ‘Blaxploitation’ as in any way negative, derogatory, or limited to films that deal with drugs, crimes or are necessarily set in the ghetto.” (7) Howard’s unapologetic, often charming, fondness for Blaxploitation is both the book’s best asset and its greatest limitation. The book gives the films their due, yet, at times feels overly compensative in its efforts.

In our present moment, Blaxploitation’s meaning is found somewhere in a mixture of droll celebration and sober analysis.

Howard exponentially expands the catalogue of Blaxploitation. This is no small matter considering that one of the hallmarks of the era is its sheer number of films. Indeed, these were, for the most part, true Grindhouse pictures. Part of Blaxploitation’s aesthetic charm is found in the oversights of slapdash products that were rushed to theatres to get in on the craze. (Think boom mics appearing in a scene with a mirror, or roundhouse kicks that never connect but still send henchman toppling.) Nonetheless, Blaxploitation Cinema includes entries for nearly 300 films! This is at least three times as many films as previous Blaxploitation scholars have suggested constitute the genre.4 One the one hand, the sheer capaciousness of Howard’s book makes it an outstanding, and genuinely enjoyable, reference guide. In such a far-reaching genre Howard’s archival due diligence exceeds expectation. He includes many little-known, largely forgotten, and in some cases, literally lost films in his catalogue. I challenge any Blaxploitation fan not to find at least one unseen title in this collection. If part of the joy of obscure culture fandom is the obsessive fulfillment of finding that one thing that your fellow enthusiasts have not seen, then this book delivers potential bragging rights. Yet, it is not merely that Howard has hunted down obscure titles. He has extended the criteria for what films should be considered. Notably, Howard emphasizes the largely overlooked transnational element of Blaxploitation. He explains, by way of his inclusion of titles like the Korean-made Soul Brother of Kung Fu and Italian melodrama Mandinga, that several films were “imported to America, often retitled, and redistributed as Blaxploitation films.” (7) Principally understood as an American phenomenon his incisive stress on transnational contributions suggests a bilateral discursive exchange between American iconographies of Blackness and Exploitation film hubs like the Philippines and Australia. Moreover, he compels consideration of the interplay of genre films (from kung fu to noir) that are often incorrectly understood as distinct from Blaxploitation.

Unfortunately, Howard’s generous inclusivity also leads to an unsteady sense of the collection’s guiding parameters. Were all 1970s films Blaxploitation films? In short, for Howard the answer is, yes. This answer sets him apart from others who consider the genre to have tapered out mid-decade and who define Blaxploitation relative to other “Black films” (a fuzzy term itself) of the era. Genre definitions, and the canons they produce, rely upon boundaries. What something is at core is recognizable by what it is not. To this end, while definitions of Blaxploitation are consistently guided by themes of antiheroic vengeance over institutional powers and stark urban aesthetics backed by soul music soundtracks, they rely on a bedrock idea that not all Black-casted 1970s films fit the Blaxploitation bill. For instance, the impressive co-edited effort of Novotny Lawrence and Gerald R. Butters Jr, Beyond Blaxploitation (2016), makes clear that films like the critically acclaimed period drama Sounder (1972) or art-house masterpiece Killer of Sheep (1978) offer stark borders between Blaxploitation and the varied “Black films” of the 1970s. However, for Howard, Sounder, Killer of Sheep, as well as other Black-casted films of the era, like the familial comedy Claudine (1974), and the High School Bildungsroman Cooley High (1975) are Blaxploitation. Even more distinctive is Howard’s argument that several, what he calls, “grey-area” (7) films, like Mel Brooks’s sendup Blazing Saddles and pathbreaking fantasy The Omega Man, which rarely even carry the “Black film” label, also qualify as Blaxploitation. The inclusion of these films is not an oversight. They are indicative of his specific definition, which is not beholden to any thematic or aesthetic criteria, let alone those prevailing ones most often used to define Blaxploitation. In fact, as noted, Howard is antagonistic to the presumptuous association of Blaxploitation to terms like “urban” and “action-thriller.” Instead, the author understands Blaxploitation as a period. Namely, the decade of the 1970s. For Howard, these other “Black films” and “grey-area” films either were “giving the green light to capitalize on (and exploit) the financial success and popularity of the easier to categorize action-oriented Blaxploitation pictures” or were “heavily influenced by the concurrently popular Blaxploitation film genre.” (7) His point is well-taken. Black filmmakers, and to an extent all filmmakers, were compelled to orbit around Blaxploitation during the early and mid-1970s. However, this willful ambiguity leaves readers wading through a collection of films that is vague in defining the terms of their bond. Howard’s determination to expand the canon ultimately obscures definition more than it asserts it.

The book is part unabashed celebration of Blaxploitation films and part meaningful assertion of their relative merit. Yet, necessarily set in the echo of its precarious origins, Howard’s effort, through no fault of his own, is always hampered by its contingence on unseating the restrictive and negative associations of the films.

This said, if there are comprehensive questions regarding the collection of films included, the actual film entries themselves are consistent and solid. Howard’s writing is a sturdy combination of concise narrative overviews, contextual details about production, and informed critical judgment of each film’s merit. He seemingly cannot help the latter. Nor should he. The movies are meaningful to him, and the tone of his entries reads more as earnest motivation to distill vast knowledge than as the recitation of an untrustworthy enthusiast. Although his voice is enjoyable and the entries are informative, a single author encyclopedia risks being too consistent. Especially when it is written by such an avid fan. Varied authors allow for specific expertise, variation in emphasis, and protection from unilateral messaging. A version of this work that called upon a cohort of Black Film Studies scholars and Black Cultural Studies scholars would make for a valuable companion to this text.

Efforts to define Blaxploitation are ironically hampered by its recognizability. Indeed, this “I know it when I see it,” aestheticism stamps the genre as viscerally identifiable and frustratingly undefinable. Despite his effort, Howard does not resolve this conundrum. And that is just fine. The book, like the films it so diligently and enjoyably archives, represents an agentive object in a long-standing, and seemingly unending, contentious discourse of Black cinematic representation. That is to say, the collection may be “essential,” but it is not definitive. The issues of ambiguity in defining Blaxploitation are invariably connected to the precarity of its legacy. As noted, the term Blaxploitation was introduced as a clear critique by Junius Griffin and all those who followed his lead. The term signified objectionable thematic material that ostensibly reinforced long-standing racist myths. As such, reconfiguring this term and those films that meet its flexible definitional mandates as one of celebration requires some perhaps irreconcilably paradoxical, discursive gymnastics. Yet Howard is up for the challenge. He does not resolve the debate, but he nourishes it well. Indeed, readers will walk away with a stake in the debate, and more than enough material to shape their own take on these undeniably Ba(a)d films.

Note: A special thank you to all my students in “From Shaft to Django: The History of Blaxploitation” for your considerate attention, enjoyable debates, and lasting insights.

1 “NAACP Blasts ‘Super-Nigger’ Trend,” Variety, August 16, 1972. p.2.

2 Headed by Griffin and composed of representatives from the NACCP, CORE and SCLC, the organization, CAB (Coalition Against Blaxploitation), proposed a separate rating system for Black films. However, the group was short-lived and never developed a rating system.

3 O’Neal was, at the time, and remains, one of the most thoughtful defenders of Blaxploitation; his position on the critiques of “so-called intellectuals” are best made in, “Black Movie Boom—Good or Bad,” The New York Times, December 15, 1972, sec 3, p. 19, as well as O’Neal’s 1972 appearance on episode 3 of the short-lived James Earl Jones-hosted television series, Black Omnibus. It is also worth noting that Gordan Parks, director of Shaft, refused to be interviewed for the section of Howard’s book “Q&A: Ten Directors Discuss Their Films.” Parks abhors the term Blaxploitation and even when efforts have been made, like Howard’s celebratory recasting of the term, he has held firm in his dissociation.

4 Ed Guerrero, for instance, suggest the number is sixty.