Years ago, I pitched a story to a small writing collective where I would participate in a Legends Football League (LFL) tryout in Los Angeles to describe the experience and determine how “serious” the league took the sport and its athletes. The planned critique of the institution formerly known as the Lingerie Football League felt easy enough, given the organization received a significant amount of press in the years prior regarding its labor practices and misogynistic marketing. I had not stepped into a football role or position since high school powderpuff games, where for one moment in time, I felt powerful in the secondary, creating my version of the great NFL cornerback Darrelle Revis’s Revis Island and refusing any receiver approaching me. At that tryout, I had a small taste of that adrenaline as we went through stretches, cardio, and standard football drills to assess our conditioning and coordination. I left the tryout that day unsigned but impressed. On the field, the range of bodies and previous athletic careers showcased incredible talent. It also reminded me what women would have to take off to suit up as coaches reminded us of the LFL’s required skimpy uniforms before we began our warmups.

When they are not on the field scoring touchdowns or tackling their opponents, the women of the NWFL are renaissance women touring the world in bands or cruising bars for love interests.

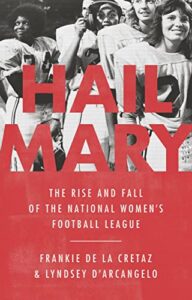

Since that day, more opportunities have existed for women in American football than ever. According to the latest TIDES report, women comprise 38.8 percent of current National Football League (NFL) league office roles, 25.3 percent of team administration, and 1.5 percent of assistant coaches. They are nearly half of the league’s fans, and now both coach and officiate at the high school, collegiate, and professional level, signaling a shift (however slight) on the male-dominated gridiron. At this moment, it feels more necessary than ever for fans and scholars of the game to draw longer lineages of women’s participation in football, a contribution that Frankie De La Cretaz and Lyndsey D’Archangelo offer in Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League (2021). Through their work, the “bionic femmes” and “60-minute women” detailed are filed into the narrative of football, breathing life into a league too many forgot. In resurrecting the vibrant athletes of the National Women’s Football League (1974-1988), readers meet passionate players willing to sacrifice their bodies, relationships with their families, and athletic careers in other sports—all for the love of the game. Rose Low, a five-sport athlete, faced the growing pains of being a pioneer when no one could tell her whether her amateur status was in jeopardy (she was eventually able to row for Cal State Long Beach and play for the Dandelions). Another NWFL player, Jan Hines, told her athletic director at the University of Oklahoma that if forced to choose between college sports and pro football, she would walk away from OU Athletics in a heartbeat. “I’m not giving up football. That’s my game,” Hines says. “That’s the only thing I’ve ever wanted to play my whole life. That’s what I’m the best at, and that’s what I want to play.” When they are not on the field scoring touchdowns or tackling their opponents, the women of the NWFL are renaissance women touring the world in bands or cruising bars for love interests.

Throughout Hail Mary, De La Cretaz and D’Arcangelo describe the athletes of the league as “women who were subverting societal norms, doing something they were told women shouldn’t do, at a time when expectations for women were even more limited than they are today.” While they primarily focus on the NWFL, they also offer a broader lens on the sport’s hold on American culture throughout the twentieth century and how the shifting landscape of women’s sports coincided with Title IX, even if it seemingly foreclosed football as an option for girls and women. With wild optimism, Joyce Hogan, part owner of the Los Angeles Dandelions, told the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, “If women’s tennis and women’s golf can make it, why not women’s football?”

The many “why nots” of women’s football echo throughout this book and the league’s history. One potential answer to Hogan’s question might be in the perceptions of the “right” sports for girls and women, with football identified beyond the limits of the appropriate. These collective understandings of what women should or could not play pushed many of the NWFL’s athletes to hide their participation in the league, with some players finding unanticipated support from their loved ones. When Jan Hines began playing for the Oklahoma City Dolls, her father, an engineer at the local TV station, discovered she was on the team when he previewed an NWFL-related news package set to air that evening. Like several other parents of NWFL players, he expressed pride in his their daughters’ athletic accomplishments. Another player, Susan Hoxie, told the authors, “[my father] spent the rest of his life bragging about me.” However, familial support did not necessarily reflect the financial reality of the league during its run in the ’70s and ’80s. “Society as a whole had a lot of catching up to do with the idea of women showcasing their physical and athletic ability in such a masculine-coded way,” De La Cretaz and D’Arcangelo write. “But how long would that take?” Throughout the book, I wondered how sports in the United States would be different if football opened for girls and women at the Title IX turn (on the K-12 and collegiate levels). I want to say the world was not ready for the league then, but I am still unsure if we are prepared for everything these athletes would be willing to offer us even today. The many issues that plagued the NWFL—travel costs, league-wide organization, meager pay, low attendance, bad officiating, and demeaning media coverage—sound eerily familiar to my research in women’s basketball today.

Hail Mary reminds us of the importance of authentic investment in women’s sports. We meet men like Sid Friedman and James Eagan, who financed teams but failed to fully invest in growing the game for women. During budgetary cuts, player health insurance, worker’s compensation, and safe field conditions often became the first casualties. When teams are too good, these men ask players to throw games. When players are read as too much like their male counterparts, they are asked to wear dresses. Treating women’s sports as a sideshow or attempting to “sex them up” for Hustler forced the NWFL’s athletes to push back against media narratives and those so-called advocates minimizing their athletic abilities and placing them in harm’s way. Eventually, these disagreements caused teams like the Toledo Troopers and Detroit Demons to declare their independence, rejecting coaches and owners who failed to envision the league’s full potential and ensure their safety.

The many issues that plagued the NWFL—travel costs, league-wide organization, meager pay, low attendance, bad officiating, and demeaning media coverage—sound eerily familiar to my research in women’s basketball today.

The undercurrent of this book grapples with the sporting archive—who is worth remembering, commemorating, or “saving” in our collective memories. The authors are transparent in their research process, acknowledging the gaps and silences that plague their attempt to tell the NWFL’s story. Basic statistics, final scores, schedules, or season results often left them with conflicting (or wholly absent) information. As the authors write, this erasure happens first in the moment with a lack of local or national media coverage. It then occurs when photos, financial records, or ephemera are discarded or otherwise lost, often when teams shuttered or transferred ownership. Many of the photos and other clippings throughout the book are courtesy of the athletes themselves, but even an archive from below is rife with loss. For example, Peggy Hickman, who played for the Houston Herricanes, lost her entire trove of the team and NWFL-related memorabilia in a car fire. This tragedy also points to the fragility of this textual history when not scanned or stored in safekeeping. Each year, as players and advocates of the league pass away, the living memory of the highs and lows of the NWFL also fades away. “If there’s no one to tell the story, did it ever happen at all?” the authors ask.

In recovering the NWFL’s voices, there is perhaps a desire to see these players as feminist icons, fully engaged in the political contributions of a women’s football league amid second-wave feminism in the United States. However, this stalls when players themselves reject this connection; Gwen Flager of the Houston Herricanes is quoted saying, “We just wanted to play football. It’s not any more or any less than that.” Others found themselves lumped into a feminism they felt did not represent them, whether as working-class, Black, or queer women rendered outside of the middle-class White sensibilities of the mainstream movement. Even still, many of the quotes reflect a desire for gender equity and the possibilities of proving that on the field. Rose Kelley of the Herricanes is quoted saying, “Women don’t have a lot of opportunities to prove they can do what a man can do,” while Columbus Pacesetters founder and player Linda Stamps told the authors, “[NWFL athletes] owned their bodies. That’s the kind of thing football did for women.”

At its best, the book not only recovers but situates the league in a broader sociocultural context. Hail Mary considers how the NWFL offered a safe space for queer women (with other LGBTQ-plus spaces subject to raids by law enforcement) and how the employment of Black head coaches occurred in a moment when the NFL systematically excluded legends such as Marion Motley and Bob Edwards. The authors also show the unevenness of marketing women’s sports. Black women athletes such as Linda Jefferson of the Toledo Troopers were considered stars on the field but faced concerns that their popularity would not translate to selling magazines or products. The book concludes with the painful death of the league in the late 1980s (although teams folded slowly several years prior). The downfall of Midwest teams in the NWFL coincided with the mass exodus of industry from Detroit and Toledo; the Demons and Troopers “crumbled alongside the economies of their hometowns.”

In recovering the NWFL’s voices, there is perhaps a desire to see these players as feminist icons, fully engaged in the political contributions of a women’s football league amid second-wave feminism in the United States. However, this stalls when players themselves reject this connection.

Readers are left grappling with the fascinating, addictive world of football after the NWFL’s demise, forced to face the reality of loving the game while reckoning with its effects on athletes’ bodies (such as CTE). Even with women continuously relegated to the periphery. Even when the game does not love us back. Like the athletes of the NWFL, we are left without closure. There are no easy solutions, no clear path ahead. De La Cretaz and D’Arcangelo write that “Throughout the NWFL’s run, there were always women eager for a chance to play football; it was the fans and owners who gave up on the venture.” The question then moves from Joyce Hogan’s question of “Why not women’s football?” to “What if the NWFL survived?” In the book, economist David Berri reminds us of how long professional men’s sports teams and leagues typically take to become profitable. In the decades before they became financially viable, there was a constant investment and a willingness to spend to win. In contextualizing this, he argues that “The NWFL would be fifty years old now [and] they’d be making tremendous amounts of money had they simply just kept going.” In this year marking the fiftieth anniversary of Title IX, another landmark moment for women’s sports, leagues like the NWFL remind us of what could have been and perhaps more importantly, the work still left ahead.