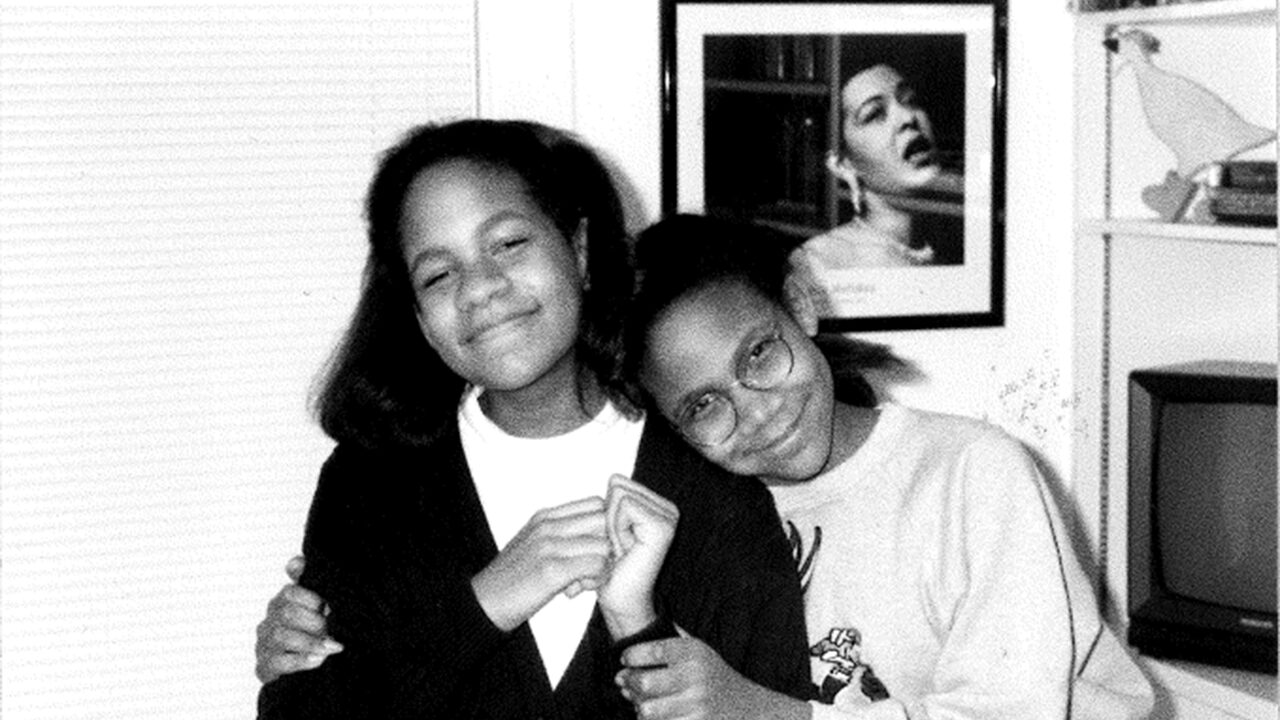

Linnet Early Husi, “Big Sis”

“Are you sure you want to do this?” my hairdresser asked me. “Once we do this, there is no going back and you have such beautiful hair.” She set down the scissors, looking at me in the mirror.

“It’s just hair. It will grow back,” I said.

“But to chop it all off,” she sounded forlorn. “Does your husband know about this?” she asked. The fact that my hairdresser was reluctant to cut my hair was annoying, but asking me if my husband approved made me angry.

“He doesn’t care what I do with my hair.” That was dishonest. Actually, he had no idea what I was doing with my hair. I had moved into a domestic violence shelter with my two children earlier that week. I no longer had any money to get expensive relaxers (chemical straightening treatments). I also did not have any time, since my entire day was consumed with physical therapy, working, and meeting with my divorce attorney.

I looked at my hairdresser looking at me in the mirror. If someone had told me as a child that I would one day volunteer to wear an Afro, I would have thought they were nuts. After wearing an Afro for one year as a fourth-grader, I vowed to never wear that hairstyle again. I was picked on endlessly for being one of the only Black kids at school with funny hair. The other person with an Afro was my younger sister. Kids called us the fungus sisters. During this tough time in my childhood, I used to wear a towel on my head in the evening after drying off from my bath. I loved wearing the towel on my head and pretending that it was hair, a wig. Long, straight, easy to manage, and socially acceptable, even if the towel was green. That is what I wanted my hair to be. An Afro gave me none of that.

Being a social pariah was hard. The few friends I had mostly vanished because they did not want to be bullied by association. The school did little to help. In fact, the counselor encouraged my parents to change my hairstyle into something more acceptable. My dad often tried to cheer me up by taking my picture. My mom dressed me in bright pink and purple outfits when a stranger mistakenly thought I was a boy.

I looked at my hairdresser looking at me in the mirror. If someone had told me as a child that I would one day volunteer to wear an Afro, I would have thought they were nuts.

But the damage of being picked on every day took its toll. By the end of the year, despite the pictures and cute outfits, my self-esteem was in tatters. I also had learned two valuable lessons: first, that looks matter when you are a girl; second, that I was not good-looking. These two lessons became deeply ingrained in me during my teen years. Just the mention of the word Afro would cause me to panic. I started relaxing (chemically straightening) my hair in fifth grade and did my best to bury the Afro chapter of my life. Until my senior year of high school.

• • •

I wanted to live abroad when I graduated from high school. I was excited to leave the United States, see my native land from someone else’s perspective. I had spent a magical summer in Italy and Greece when I was fifteen, living with a family and traveling, and I was eager to do that again. I wanted an adventure and to experience a different way of living.

But what to do with my hair? By senior year I was a pro at getting relaxers. I had my own car so I could drive to the appointments and pay with my mother’s credit card. I styled my hair many different ways, but relaxers happened every eight weeks like clockwork. I took my hair very seriously. When I visited Italy and Greece for three weeks, I did not think about my hair except to pack volt converters, a hairdryer, and curling iron, and rollers to wrap my hair at night. But I knew if I was going to live overseas, I would need a simpler hairstyle, one that did not involve toxic chemicals. I knew I needed an Afro. The very thought filled me dread. I did not want to be bullied again, be told I was ugly, that I did not fit in. I did not want to be in fourth grade again.

After my graduation, I chopped my hair. I figured that, since I was out of school, I would not have to deal with too much name-calling since the only people who would see it would be my co-workers at the daycare center where I worked. My Hispanic hairdresser was very approving. She pierced my ears and I wore a pair of sparkly blue earrings with my second Afro. When I showed up to work after my haircut, I was amazed by the reaction. Everyone loved it! There was no teasing, only praise. I was shocked. I never thought an Afro could be cute.

The Dutch were fascinated with my hair in a way that I had never experienced in the States. Whenever I got a haircut, the hairdresser always asked me if she could show my hairstyle to the other hairdressers. I shrugged, thinking the request was really odd.

In the end, the Afro was the right call for living in Europe as a Black woman. It was very easy to keep my hair super short. It was also very cheap. I could use whatever shampoo and conditioner I found at the store. I could wash my hair every time I took a shower. It was easy to find a hair salon that would cut my hair. Plus, the haircuts cost next to nothing, which fit my meager budget.

The Dutch were fascinated with my hair in a way that I had never experienced in the States. Whenever I got a haircut, the hairdresser always asked me if she could show my hairstyle to the other hairdressers. I shrugged, thinking the request was really odd. After a bunch of other Dutch hairdressers marveled at how curly my hair was, I would leave the salon with mixed feelings and a deep longing for straight hair. When I returned to the United States, the Afro quickly changed to a more socially acceptable straight but curly hairstyle that ended up being more work, more time, and more expensive than a relaxer. I kept that hairstyle until I got married. Then I went back to relaxers.

Over the years, I have had some bad relaxers. I even got a chemical burn when a relaxer stayed on my scalp too long. But despite these hiccups, I always considered myself lucky; my hair loves toxic chemicals. Many Black women experience breakage when they use relaxers. I never had that problem. My hair grew long, strong, and fast. It made me the envy of other Black women, including some of my hairdressers.

• • •

“That’s you? Man, you looked good!” Wendell, one of my more outspoken eighth-grade students, was looking at a picture of me taken shortly after the birth of my second child. My jet-black hair fell neatly to my shoulders. Jocelyn, another student, looked at the picture and was horrified. “You had such pretty hair. Why did you cut it?” It is not lost on me that Jocelyn has very short straightened hair. More than likely, her hair was so short due to breakage. I feel uncomfortable that my students, all of whom are Black, were so upset that my hair was not relaxed anymore. I am more annoyed at myself for not feeling confident with my decision to wear an Afro. I can feel the same shame I felt as a fourth-grader creeping over me. My wish for socially acceptable hair returns. Instead of talking about these complicated emotions tied to Black hair, or teaching students that we have all been brainwashed to achieve a European beauty standard, I snatched the picture back and hustled the students back to the assignment, ignoring their comments and the pain they caused.

The next day I got my hair cut and asked the hairdresser if she did relaxers. She explained that she does not; she only cuts hair. She explained that she can do more haircuts in one day than she can do relaxers. She asked me if I was thinking of getting a relaxer.

“Yeah, I guess so. I should probably start coloring my hair, too. It’s getting awfully gray. I don’t want to look old.”

“You gotta color on week six or seven and relax on week eight. You can’t do both on the same appointment.” She was matter-of-fact.

“Oh. That’s more work than I thought,” I said, mentally calculating how much that would cost and how many babysitters I would need.

I like that I no longer have negative feelings about my natural hair. I now see the teasing that I suffered as a child for what it was. I like that I meet more and more Black women who wear Afros. I like that my hairstyle works with being a single, working parent. I like that my children think my hair is normal and cannot remember a time when I wore it differently.

“It’s always a lot of work to be something you’re not. Lots of money too,” she said as she began to cut my hair. Her words struck me. For years, I had relaxed my hair in an effort to fit in. To be accepted by my White peers. Did I really want to do that again? Did I want to be something I am not? I had done that during my marriage, pretending to be happy when I was secretly afraid and unhappy. After I moved into the shelter and got my third Afro, I thought I had reached rock bottom in my life. I kept telling myself that the Afro was a quick fix. When I got money and a safe place to live, I could worry about my hair. The Afro allowed me to focus on the other ninety-nine problems I was facing by trying to leave my abusive ex-husband. I never thought of this hairstyle as being authentically me.

But now three years have passed, the longest I have kept an Afro, and I have no plans to change it, despite having a job, safety, and a home. I like the ease an Afro provides me. It fits my new life. I like that I no longer have negative feelings about my natural hair. I now see the teasing that I suffered as a child for what it was. I like that I meet more and more Black women who wear Afros. I like that my hairstyle works with being a single, working parent. I like that my children think my hair is normal and cannot remember a time when I wore it differently.

I have not watched any tutorial videos on how to care for an Afro or how to style it. I hear you can do a lot with it but it can be quite time-consuming. Instead, I wash and deep condition it, and rub mousse in it to define the curl when I have the time. I keep telling myself that one day I am going to learn more ways to style my hair, which is a pretty good sign that I have no intention of returning to a relaxer. I have decided to embrace my Afro as a symbol of my new life and my new-found freedom.

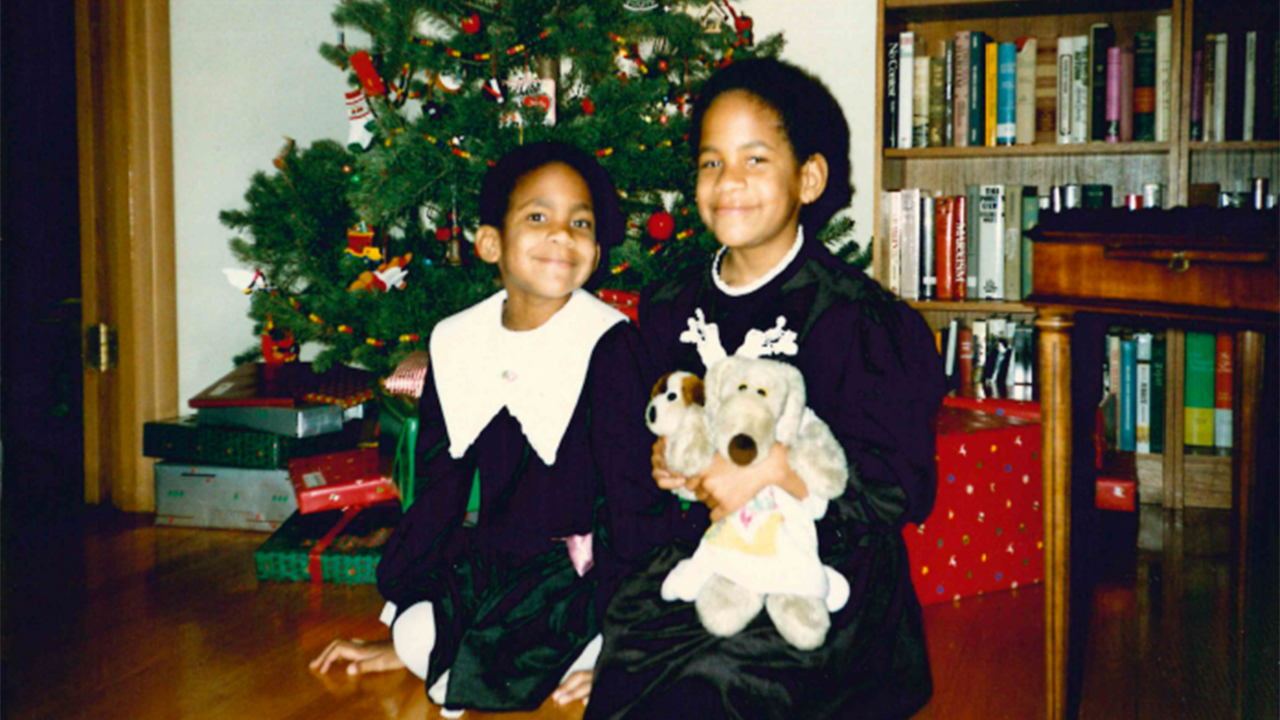

Linnet Early Husi (left) and Rosalind Early, Christmas 1988 in St. Louis. (Photo courtesy Early family)

Rosalind Early, “Little Sis”

When I was in third grade, my mom said she was sick of dealing with my hair. I had not given a lot of thought to my hair at that point. It was something I let my mom worry about. She would do the work of washing it and pulling it into tight braids that pulled on my scalp.

After I had nearly drowned in a neighbor’s pool, my mom decided my sister and I needed swim lessons. They probably did more harm than good, as I was terrified of the lessons. I would walk up to the pool in my bathing suit, my teeth chattering, my gut rolling, and then thrash around anytime I was forced in the water. To this day, the smell of a pool makes me anxious. Plus, the lessons did not help since, a few years later, I again nearly drowned in a neighbor’s pool.

Be that as it may, the swim lessons meant my mom was always doing my hair. She said she wanted us to get Afros. So my sister and I went to the hairdresser and got our hair cut.

I do not remember having much of an opinion about the style. The fact that my sister had the same haircut probably helped because I looked up to her. It also helped that it was summer. It is hard to imagine how unself-conscious I was that I would not care that my hair was completely altered. Years later, I would sit in a hairdresser’s chair crying because she had made my hair too curly (think Shirley Temple curls). But I was seven or eight or however old you are in third grade and mostly cared about Barbie dolls. That there was hair on my head seemed to be enough.

Then school started.

School and I had an uneasy truce. I did all right academically, but I was completely mystified by social interaction. I had one friend, which had been hard enough to get, and when she did not come to school, which was rare, it was not unusual for me to spend the whole day in complete silence.

The fact that my sister had the same haircut probably helped because I looked up to her. It also helped that it was summer. It is hard to imagine how unself-conscious I was that I would not care that my hair was completely altered. Years later, I would sit in a hairdresser’s chair crying because she had made my hair too curly (think Shirley Temple curls).

I went to Old Bonhomme Elementary School in Olivette. Looking back on my class pictures, it was usually me and one Black boy or no Black kids at all. It was also, not to date myself, the 1980s, so these kids and the adults around them were not exactly woke. Already a quiet, nerdy girl who had glasses and squinted a lot, I was in for a world of hurt.

My sister and I were not in the same grade, but we rode the bus home together. The first day, kids asked us what was wrong with our hair. We were dubbed the “fungus sisters” and teased till we were crying. We headed home and told our dad what happened.

My dad had this disdain for the world that, when you are eight, you cannot even understand, let alone mimic. The opinions of your peers matter. But my dad said to ignore those stupid kids. He even looked up fungus in the dictionary to defang the word for us. “The plural of fungus is fungi,” he said. “These kids don’t even know what they’re talking about.”

As strategies go with dealing with bullies, I cannot recommend this one. Sorry, dad. I retreated into myself even more. Some of the sadistic kids in my class picked on me constantly. I would cry silently as they flicked stuff at me to see if it would stick in my hair. We sat at long tables that they would push so they would dig into my abdomen. I was young and it was painful. Even now, I feel bad for that eight-year-old girl.

The good news was that my one friend stayed true, even through my descent to social pariah status at school. No one else was really very helpful. One over-eager guidance counselor tried to convince my parents that I was learning disabled because I was so quiet. He thought my sister had one too; I guess diagnosing learning disabilities was the rage among education professionals. He was an idiot.

Fortunately, by fifth grade the whole thing was over. We moved to a new school district and my mom introduced me to the “creamy crack”—the nickname for relaxers, a hair straightening treatment for people with very curly hair. I got my first relaxer, and when I showed up at school, no one called me anything. I still was extremely shy and struggled to make friends, but the bullying stopped.

(I mean, it started again as we all went through puberty, but it was for just being alive and wearing clothes the other kids disapproved of or whatever stupid stuff kids pick on each other for.)

Obviously, after that I was insistent about my hair. No Afros. Straight hair only. As I got older, I learned about the politicization of Black hair. Wasn’t I a self-hating Uncle Tom for wanting to straighten my naturally curly hair?

I retreated into myself even more. Some of the sadistic kids in my class picked on me constantly. I would cry silently as they flicked stuff at me to see if it would stick in my hair. We sat at long tables that they would push so they would dig into my abdomen. I was young and it was painful. Even now, I feel bad for that eight-year-old girl.

I remember one time, I was drinking at a water fountain. I was in seventh grade. My hair was pretty long and spilled oh so slightly into the water fountain. I lifted it out, just like I had seen the White girls doing. I was secretly thrilled. Three Black girls walked by and mocked me for thinking my hair was long enough to have to lift out of the water fountain. I thought I was a White girl, they said. They pushed my head into the water fountain.

It would be great now to start talking about how my hair was this metaphor for integration. I wanted to fit in at predominantly White institutions and learned the hard way that you can be too Black. I hid some part of myself and that in turn made me an outcast among my own people.

But most of those girls had straightened hair, so the metaphor does not really work. I was not pretending I was White by straightening my hair. But lifting my hair out of the water fountain was too great an affectation. As the water shot up my nose, it was a reminder, you can be too Black for Whites but you can also be too White for Blacks.

What I learned was that hair is complicated. On the one hand, I was keeping my hair straight because I thought it looked good. But was the only reason I thought it looked good was because of hundreds of years of White supremacy reinforcing the idea that straight hair was better?

On the other hand, did it really mean I hated some part of myself just because I straightened my hair? Was I really freeing myself from White supremacy if I gave up my hairstyle? (I mean, if you do something just to prove you are not giving into White supremacy, are you simultaneously giving into it by letting it guide you at all?) What was more authentic? Is wearing your hair a certain way some sort of race loyalty oath? Do White girls ever have to think about stuff like this?

I was jealous of White girls because no one cared how they did their hair (except maybe their parents). They could chop it off, shave it, dye it, curl it, grow it long. No one said they hated themselves because they all wanted to be blondes.

Over the years, I did not outgrow the conundrum. It became less important, but always bedeviled me. I also did not give up my straightened hair, keeping it up while I lived abroad, when I was broke (getting relaxers is expensive), and even after I developed psoriasis on my scalp (which definitely was due to twenty consecutive years of putting relaxer on it). But then, finally—primarily due to psoriasis—I decided that my head needed a break. It was time to go back to a natural. My sister had one, and she described a life with low beauty bills and a style that was easy to maintain even if you were exercising heavily.

I told my hairdresser what I was thinking. “It’ll be cheap and easy,” I concluded. “What do you think?”

“Easy and cheap,” she said. “Yeah, those are the words people want to use to describe their hair. Besides, wearing your hair natural isn’t easy.”

I paused. Wait, was my Black hairdresser trying to talk me out of returning to my roots? My woke hairdresser? I offered a few counterarguments, but she told me to keep my hair how it was. “It’s easier to deal with like this,” she assured me. “You like to pull it back and forget about it.”

Laziness, surprisingly, was a big factor in me keeping my hair straight. The cynic in me figured my hairdresser just wanted to keep me as a client, which was why she was trying to talk me out of it.

“Well, don’t you think it’s better to wear your hair natural?” I asked. I did not say Blacker, but I meant Blacker. She maybe sensed that.

Wait, was my Black hairdresser trying to talk me out of returning to my roots? My woke hairdresser? I offered a few counterarguments, but she told me to keep my hair how it was. “It’s easier to deal with like this,” she assured me. “You like to pull it back and forget about it.”

“People wear their hair all types of ways,” she said. And she was right. My Black friends played around with their hair as much as White girls. They got weaves and braids and wigs and dreads. Most people did not take their hair that seriously. Not as seriously as I did, the girl who did not let anyone cut her hair shorter than a half-inch trim for more than a decade. Other people were having fun. Those kids who cared about how I wore my hair had disappeared years ago. I had been arguing with their ghosts for decades.

“That’s true,” I said. “Well, then, I guess I’ll just take the usual.” And when I put my glasses back on and looked in the mirror at my freshly laid hair, I smiled. I looked like me, which was exactly what I wanted.

Ah, Black girl, heal thyself.