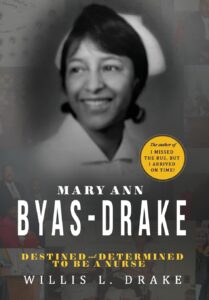

Mary Ann Byas-Drake: Destined and Determined to be a Nurse

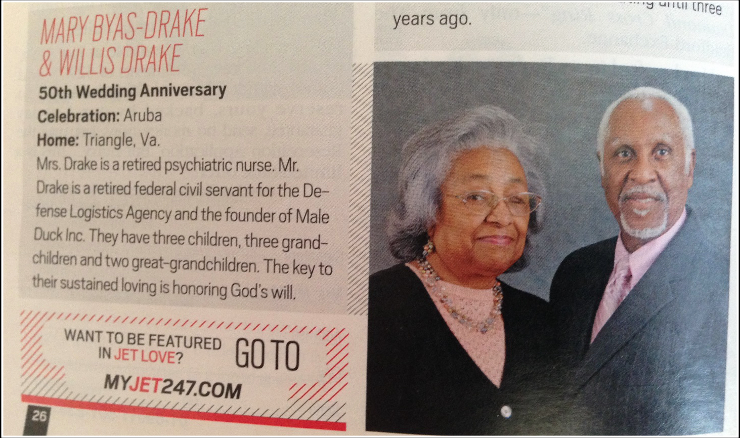

Willis L. Drake’s Mary Ann Byas-Drake: Destined and Determined to be a Nurse (2023) is, in its way, a modest project, homespun, and deeply heartfelt. A husband loses his wife of fifty-five years in 2015. She lost her left leg due to sepsis shock, from which she never fully recovered, and was on dialysis treatment at the time of her death at the age of 74. Willis and Mary had been together since young adulthood. This is a hard loss for the surviving spouse. So, he decides to write a book in her honor. It takes him a year and a half to do so. “I am sure that I was grieving,” Drake told me, “and writing the book was very therapeutic for me at the time.” It was initially “a brain dump of the memories that Mary and I created over our life’s journey.” The original manuscript was over a thousand pages long, an enormous outpouring about the person with whom he co-created a form of reality that nurtured them both.

Mary Ann Byas-Drake (bottom row, far right) with the Homer G. Phillips Memorial Hospital Nursing Class of 1962. (Photo courtesy of Willis L. Drake)

Some might have stopped there, having reached a catharsis. There would be no particular need to publish it, as the effort would serve just as a highly personal memorial, an excessively long eulogy that would only interest a surviving spouse. Surely, by writing this manuscript, Drake had exorcised a ghost or at least learned to feel comforted by its presence rather than ravaged by his wife’s absence. He had performed an important duty for himself: the emptiness caused by his wife’s death had become a bit less gaping a wound. It was a pain he could now endure.

Here is the intersection of a young Black woman, wife, and expectant mother, asserting herself; her family fighting on her behalf; and a Black institution willing to make an exception for someone who it thought was worthy of it. For Black readers, this is a kind of catnip narrative of how we might work together to make a true community.

But Drake hired an online professional editing company to pare down the work and patiently sought out publishers, finally choosing Palmetto Publishing. Moreover, Mary Ann Byas-Drake is a self-conscious, self-aware construction; it is also not Willis Drake’s first book. I Missed the Bus, But I Arrived on Time (2019), where he admits he is “not a trained author,” is a straightforward autobiographical account that focuses in great detail on his growing up in Black St. Louis—far more detail than Mary Ann Byas-Drake—and describes being an amateur boxer and what it taught him, his struggles with racial discrimination, his family’s strong religious faith, meeting Mary Ann Byas, and their marriage. Some of the same ground is covered in his second book, but Mary Ann Byas-Drake is more of a sequel than a mere repetition. The books represent different frames of mind for the author.

What may be most instructive in understanding Mary Ann Byas-Drake is how Willis Drake describes his father in the prologue to I Missed the Bus, But I Arrived on Time:

“My father was my role model and my ambitions were to be like him. He always provided for his family. We had a roof over our heads, food on the table and nice clothes to wear. My friends always had a cool word to say about my dad; they would always say, ‘Your dad, Mr. Drake, is always nice and friendly to us.’ That made me proud. …

“I can’t remember that my father ever took a day off from work because he was sick. He was always at home when we were young kids, using the best parenting skills that he had in raising his family. He provided a solid Christian foundation and read the Holy Bible to us often. He instructed us on the right way to live our lives and what he expected of us.”

It is my contention that Drake was inspired by the example of his father to write Mary Ann Byas-Drake. He was doing what a good father and a good husband should do: remember his wife and how she affected his life and, more important, what her life meant to him. This explains the subhead, Destined and Determined to Be a Nurse. “Mary was seventeen (17) years old when she entered the HGP [Homer G. Phillips] School of Nursing program in August 1959” (15), Drake writes near the start of chapter five. She was still a teenager when she chose this path, which is not terribly unusual, but nonetheless a show of focus and, well, knowing what you want and why you want it. And it is this story of Mary becoming a nurse, a desire Drake senses is a calling, one that impresses him deeply, and her years in the nursing profession which, by and large, drive this narrative.

But Drake, courting young Mary, is also impressed with the Homer G. Phillips Nursing School. As he related while he waited for her in the lobby of her dormitory: “I waited for Mary, a future nurse, to be produced from this African-American hospital nursing school, HGP. At the time, I was unaware of the historical significance of Homer G. Phillips Hospital and its value to the African-American community in the [“Ville”] in St. Louis. I am not sure why, but I felt proud waiting for Mary to appear in the visitor’s lounge.” (27)

His feelings about Mary and her pursuit of nursing are tied to where she is receiving her training. This is a rather densely layered racial pride and quest for professionalism story. What makes HGP special is that Mary and Drake marry, and she becomes pregnant. Both are violations of the rules of the school. Mary should have been expelled from the program, but Miss Gore permitted Mary to stay. (Mary had two children while she was in nursing school.) In part, this probably happened because Mary spoke up for herself and because she must have impressed Miss Gore that she was a serious, dedicated student. Also, Mary’s mother “[pleaded] her daughter’s Mary’s case… [for] over an hour,” Drake told me. Here is the intersection of a young Black woman, wife, and expectant mother, asserting herself; her family fighting on her behalf; and a Black institution willing to make an exception for someone who it thought was worthy of it. For Black readers, this is a kind of catnip narrative of how we might work together to make a true community. Drake told me that his “hope is that the book will be an inspiration to nursing students specifically…” Perhaps it will be. Mary did, after all, graduate, become a registered nurse, and practice her profession for many years.

One has to be glad that a man thought so much of his wife as to write a book like this.

She worked in both the North and South St. Louis Visiting Nurses Program, was unfairly fired by a White doctor but fought and got her job back, and more than held her own among the White nurses of South City, in good measure because of the incredible training she received from HGP. In South City, most of her clients were pregnant, teenage White girls who were deeply affected by her. She related to these girls well, who perhaps saw her as an older, understanding sister. (She was twenty-five at the time.) “Mary really enjoyed her job,” Drake told me about this period in her life.

Mary Ann Byas-Drake and Willis L. Drake’s 50th wedding anniversary notice in Jet magazine. (Image courtesy of Willis L. Drake)

On the whole, Mary Ann Byas-Drake is too long for its subject matter. And more careful proofreading would have been helpful. Despite these criticisms, the book has a certain kind of richness, especially the chapters about St. Louis and Homer G. Phillips, about Mary’s early years as a nurse, about Mary and Willis as young lovers succumbing to sexual yearnings, about the thick, and sometimes moving, portrait of Black family life that all readers will appreciate but Black readers might especially identify with as something they had or something they wished they had had. One has to be glad that a man thought so much of his wife as to write a book like this.