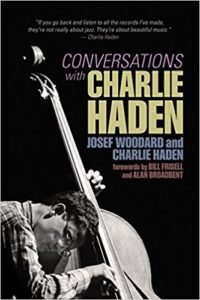

No one yet has written a biography of Charlie Haden (1937-2014), the great jazz bassist. But this book, Conversations with Charlie Haden (hereafter Conversations), is the next best thing. There are warmhearted forewords by pianist Alan Broadbent and guitarist Bill Frisell, Haden’s longtime collaborators, as well as two dozen black-and-white photographs, mostly of Haden onstage. The core of Conversations, however, is a collection of Haden interviews taken by Josef Woodard, a Santa Barbara-based music critic. The interviews, which span a 20-year period from 1988 to 2008, were originally intended as source material for feature stories about Haden in publications such as Down Beat, Jazz Times, Musician, and The Los Angeles Times. In Conversations, though, Woodard’s interviews are presented in full, allowing readers to eavesdrop on wide-ranging, intimate dialogues between Haden and a longtime friend.

Conversations will be of interest to many different audiences, from Haden aficionados who can recite his entire discography to casual fans who know him only as the bass player in celebrated jazz ensembles such as Ornette Coleman’s quartet of the late 1950s and early 1960s. To readers who are encountering the bassist for the first time, Conversations offers colorful (re)tellings of Haden stories that are now part of jazz’s folklore. Many of these autobiographical anecdotes touch on Haden’s upbringing in a Midwestern farm family that moonlighted as a country-and-western act, appearing on radio broadcasts in Shenandoah, Iowa and Springfield, Missouri, and later on television in Omaha, Nebraska. Haden describes his earliest musical experiences at home and his first professional performances—as a boy singer on the family radio show—when he was just 22 months old: “I was the youngest person in Iowa to have a Social Security card” (189). We also learn about his teenage bout with polio, which affected his singing voice and led him to take up the double bass, an instrument that he quickly mastered. In 1957, when he was just 19 years old, Haden left the Midwest and enrolled at the Westlake College of Music in Los Angeles, but he spent much of his time outside the classroom, playing at jam sessions and gigging with pianists like Paul Bley, Sonny Clark, and Hampton Hawes. Soon Haden met Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, and Billy Higgins, and they began rehearsing daily, workshopping Coleman’s compositions and developing a distinctive mode of group improvisation. The bassist discovered that Coleman’s music was unlike anything he had ever heard. As Haden explained, “[t]o play with Ornette, you have to listen to every note that he plays, because he’s constantly modulating from one key to another. So I had to listen” (113).

An earlier “pianoless” quartet, the Gerry Mulligan-Chet Baker band, improvised on traditional chord changes, but the Coleman group did not, and this gave Haden the freedom to develop a new approach to jazz bass playing, harmonically oriented yet tonally adventurous, with an inimitable, resonant tone.

Indeed, Haden had to listen attentively, and not just because the bandleader often changed keys throughout his improvisations. With Coleman on alto saxophone, Cherry on trumpet, Haden on bass, and Higgins on drums, the quartet did not have a piano or any other chordal instrument, which meant that the bassist was solely responsible for defining the harmony. An earlier “pianoless” quartet, the Gerry Mulligan-Chet Baker band, improvised on traditional chord changes, but the Coleman group did not, and this gave Haden the freedom to develop a new approach to jazz bass playing, harmonically oriented yet tonally adventurous, with an inimitable, resonant tone.

Haden’s playing style was just as revolutionary as the sound of Coleman’s white plastic saxophone, and in 1959, when the quartet made its New York City debut at the Five Spot, the response was overwhelming. On opening night, just before the first downbeat, Haden glanced across the room and saw “Percy Heath, Charlie Mingus, Ron Carter, Richard Davis, Wilbur Ware, Paul Chambers … all the great bass players were right there, standing at the bar, looking right in my face” (22). “From that moment on,” he declared, “I shut my eyes [while] playing” (22). Another night at the Five Spot, Haden recalled, “I was playing with my eyes closed. … [then] I opened my eyes and here’s Leonard Bernstein … with his ear next to my F-hole, listening. It kind of shook me up. I looked over to Ornette and said, ‘Hey, who is this guy?’ He said, ‘Never mind,’ and we kept playing. When we finished, [Bernstein] invited me over to their table, and he invited me to come up to rehearsals of the [New York] Philharmonic. He asked me where I’d studied. I told him I was self-taught. He was amazed. … I said, ‘This is about improvising, it’s not about interpreting’” (23).

In the early 1960s, Haden left Coleman’s group, but the music they made together influenced the bassist for the rest of his career. He worked with fellow Coleman-band alumni in the quartet Old and New Dreams, and echoes of Coleman’s music could be heard in Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra, a big band that played compositions inspired by the American civil rights struggle and leftist political movements from around the world. Other Haden-led projects, though, were less experimental and more traditional in sound and style, notably his Quartet West, a Los Angeles-based ensemble featuring saxophonist Ernie Watts, pianist Alan Broadbent, and (for much of the group’s history) drummer Larance Marable. Quartet West’s repertoire did include a few Coleman compositions, including a moving rendition of “Lonely Woman,” but mostly the group performed jazz standards and music from the scores of classic Hollywood films. The band was highly successful, recording several albums and performing for more than two decades, from the late 1980s to the 2010s. Some critics, however, considered Haden’s work with Quartet West to be insufficiently avant-garde for a musician who came to prominence playing free jazz (and who continued to play with Ornette Coleman from time to time). As Haden observed, “when [critics] start talking about Quartet West, they say they expected to hear something more along the lines of Ornette. It’s … coming from people who I call ‘Ornette purists.’ They have associated my music with Ornette more than any other group I’ve ever played with. They think that … whatever I do on my own should be like that. … That’s really disappointing to me, that someone can’t hear the beauty in Ernie Watts’s playing and in Alan Broadbent’s playing. I can say that this quartet is one of the best bands I’ve ever played in, too. I get tremendous fulfillment out of this band. And I think that if someone doesn’t open themselves up to this that they’re missing a lot of music, if they’re letting their predetermined attitude get in the way” (29).

For Haden, the fulfillment he got from Quartet West was much the same as the feeling he experienced with the Ornette Coleman quartet, the Liberation Music Orchestra, and in his projects with other close collaborators, from fusion guitarist Pat Metheny and Cuban pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba to a host of jazz vocalists, including his second wife, Ruth Cameron. Haden was equally comfortable playing ballads, bebop, boleros, country music, and free jazz, and accordingly, he never limited himself to playing in a single musical style. Instead, he ventured across stylistic boundaries to find creative partners who shared his values, in music and in life. “I believe,” Haden affirmed, “that all the great musicians who have ever lived, when they pick up their instrument … they’re giving thanks. They’re saying, ‘Thank you for my gift. Now I want to give back.’ People who play music from that point of view, with reverence and humility and respect for beauty and their gift, usually really make honest music” (5). According to Haden, this attitude toward music-making had both sonic and spiritual implications: “If you could approach music with that kind of giving of oneself … then you’re not playing anymore, you’re listening. … It’s really important to think of playing in terms of listening before you start to play, because it sets up that reverence. It’s almost like a religious ritual, of walking into a holy place” (11).

From his youth to his late seventies, Haden treated music-making like a spiritual practice, with an emphasis not on transcendence but rather on the here-and-now. If he treated his fellow performers respectfully while staying true to himself, the music would turn out right, and so would his life—when he acted in accordance with the values he upheld onstage.

These values were paramount to Haden, so much so that they became the foundation of the curriculum at the California Institute of the Arts’s jazz program, which he founded in 1982. Then as now, most college jazz programs focused on theory and technique, but at CalArts, Haden preferred to explore the music’s spiritual side: “The spiritual part of improvisation is, I think, 85 or 90 percent of the art form. Academics should make up just the amount you need to play your instrument and execute your technique” (136). Haden’s CalArts course, which he taught every Tuesday afternoon, was titled “Advanced Improvisation,” but he preferred to call it “The Spirituality of Improvising” (199). “What my class is really about,” he said, “is striving to achieve the level that you achieve when you play, in the other part of your life, in the everyday part. Having the quality of givingness and humility and appreciation that you have when you’re playing, in the other part of your life, which is really hard” (196).

From his youth to his late seventies, Haden treated music-making like a spiritual practice, with an emphasis not on transcendence but rather on the here-and-now. If he treated his fellow performers respectfully while staying true to himself, the music would turn out right, and so would his life—when he acted in accordance with the values he upheld onstage. As Haden used to tell his CalArts students, “as long as I’ve got my bass, I’m cool. When I put that down I’m in trouble, because I have to live up to what I’ve learned. It’s a heavy responsibility when you think about it” (196). Indeed, living life can be a “heavy responsibility” for everyone—including Haden, who beat an early-career heroin addiction and then helped raise his four children after the breakup of his first marriage. But not all of us have Haden’s equipment for living to accompany us through each day. During childhood, music started Haden on the right path, and if he ever fell away, restoration was always close at hand. All he had to do was pick up his bass and head for the nearest stage.