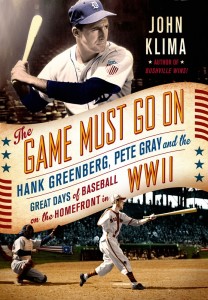

The Game Must Go On: Hank Greenberg, Pete Gray, and the Great Days of Baseball on the Home Front in WWII

At the outset, I must admit that I have never read a book quite like this one. As a former academic, I was not anticipating a style of writing like that of the author. While the content is historical and clings rather tightly to a chronological sequence roughly equivalent to the time of the Second World War, it would not be fair to consider the book a history book. The author states in the preface, “This is not a textbook or a reference book. I wanted it to be the first book to put baseball players into combat, and to let the reader discover the magnitude of their contributions by making them experience how they felt, yet rose to the occasion at the cost of personal sacrifice. I wanted the reader to feel the bullets coming at them, to smell the cordite, to see what they saw and feel what they felt.” Accepting this as the goal of the author, I conclude that he succeeded. He most certainly researched the contents extensively and did provide interesting and worthwhile statistics, accurate dates and events, and historically relevant facts about both the war and baseball.

There are three central figures in the book, two of them mentioned in the title. They are Hank Greenberg, Pete Gray, and Bill Southworth, Jr. The last of the three was never a major league player, although he did time in the minors, and his father was once a player and also a manager of the St. Louis Cardinals (a fact discussed in Chapter Three). Southworth, Sr. won two World Series during the War in 1942 vs. the Yankees and 1944 vs. the Browns. Greenberg, highlighted in Chapter One of the book, was the famed centerfielder for the Detroit Tigers and the highest paid player in the game in 1941 when he was drafted. Gray, whose path into minor league baseball was traced in Chapter Two, was lesser-known and played for the St. Louis Browns in 1945 in the last year of the War when professional baseball was at its nadir. He lost his right arm in a childhood accident. Nonetheless, baseball was his career; after several seasons in the minors he finally made it to the Browns, although he mostly warmed the bench. He certainly could field and run as well as any two-armed player, but batting was his weakness, although he did hit .218 in his only year in the big leagues. As a minor-leaguer in Memphis, he hit a home run over the fence, something that few famous sluggers could do with a one-armed swing. He was one of a record 120 rookies in the ’45 season, but by season’s end he was resigned to losing his spot as the war ended. The major leaguers in service began to return with the next generation of fit and healthy baseball prospects. The author stresses that Gray’s most important service as a player was not on-the-field performance, but rather as serving as an inspiration to so many amputees returning from the front who strongly identified with Gray and his dedication to playing major league ball. Greenberg’s return at the end of the ’45 season, along with his importance to the Tigers’ successful race for the pennant, was stressed in the final chapters of the book. Subsequently, they defeated the Cubs in the World Series. But all three of these key figures in Klima’s story were featured intermittently throughout the book, weaving the stories of the major leagues alongside the progress of both fronts of the War with considerable emphasis on Greenberg’s Army duties and assignments during his four-year hitch.

The author stresses that Gray’s most important service as a player was not on-the-field performance but rather as serving as an inspiration to so many amputees returning from the front and who strongly identified with Gray and his dedication to playing major league ball.

The strength of the book lies in how it weaves the fortunes of baseball with the dramatic circumstances of the historical era. First of all, baseball was important to the morale of the country and, in particular, to those in service. The author develops that theme nicely. He offers numerous examples of the role of the sport in the lives of those abroad in combat, both as fans and as amateur players, such as the Armed Forces World Series that took place in Europe after the surrender of Germany and the Army-Navy series in the Pacific. Secondly, the quality of major league baseball deteriorated because of the enlistment of many top players and their replacement by players of lesser ability who never would have made the majors had vacancies not been created. Either as volunteers or as draftees, popular players like Greenberg, Bobby Feller, Buddy Lewis, Virgil Trucks, Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Cecil Travis, Stan Musial, and many others were lifted from the majors to serve. This provided playing opportunities for less gifted athletes. Discussed in Chapter Ten, appropriately titled “Too Tall, Too Short, Too Young, Too Old,” there were numerous examples of war-time players exempt from service. Some were old (Mike Kreevich at 36), some very young (Carl Scheib at 16, Joe Nuxhall at 15), some exempted from service possessing physical defects (George McQuinn with a bad back, Vern Stephens with a bad knee, Milt Byrnes with a bronchial condition,) and classified 4-F, some with families or other responsibilities such as work in a war industry (Denny Galehouse) also eligible for exemption. Whoever they were and why they made the majors is explained, and their performance often described, in considerable detail. Thirdly, the War brought on changes in baseball’s future. These include the signing of the first media (radio) contract in 1945; the introduction of plane transportation which opened the possibility of West Coast expansion, racial integration, the rise of the number of Hispanic players; the introduction of “bonus babies;” the unionization of the players; and eventual free agency. Klima draws all this together systematically and in an accessible, sometimes humorous style.

An example is in Chapter Twenty. After the death of Commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, there was a bit of campaigning by Ford Frick, National League President, for the position. When his selection was blocked by Warren Giles of the Cincinnati Reds, it resulted in the appointment of Kentucky Senator Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler as a compromise candidate. Chandler was not liked by the owners for a variety of reasons, but most importantly he viewed the Commissioner’s responsibility as looking out for the interests of the fans rather than the conflicting interest of the owners. Furthermore, Chandler favored integration and saw a need for a players’ union. Both these positions were anathema to the owners, but both came to fruition. The author often indicts the owners as slave holders and provides ample evidence that there was no such thing as bargaining, collective or otherwise. The war-time owners often dealt in punitive ways with players who attempted to negotiate for salary increases. This was well-substantiated in the book. The book provides a clear distinction between antebellum and postbellum baseball as the “old days” versus modern times.

Of course, when the War began it was not at all clear that baseball—or any other professional sports—would be allowed to continue. At the time, Commissioner Landis was looking for a lead from the White House about how to proceed, fully realizing that healthy, fit, young players would be inducted into the Armed Services and that the need to conserve on resources would interfere with travel. In quick response President Roosevelt, after conferring with his old friend and Washington owner, Clark Griffith, sent Landis the so-called “Green Light” letter permitting baseball to go forward with the ’42 season. This understanding between the political leadership and baseball was not a long-term blanket agreement but rather a renewable commitment. Each year the question arose, “Would there be a season?” In ’45, for example, there almost was not. However, Roosevelt, as a fan as much as President, realized the importance of the national pastime to the American people and the necessity to provide continuity in a time of crisis. Klima notes that there were concessions such as an increase in night baseball to permit day shift workers in defense industry plants to attend, and also, an increase in double headers to minimize train travel. In fact, in 1943 there was a record 200 scheduled double headers, some games starting as early as 10:30 a.m. In the final month of the pennant race at the end of the ’45 season, the Tigers played 23 games in 16 days, including seven double headers. During this stretch, there was a seven-game series played between the Tigers and the Yankees that also included two double-headers.

Each year the question arose, “Would there be a season?” In ’45, for example, there almost was not. However, Roosevelt, as a fan as much as President, realized the importance of the national pastime to the American people and the necessity to provide continuity in a time of crisis.

Klima also portrayed a number of other players in considerable detail. Besides famous players like Feller, Williams, and DiMaggio, two of Klima’s featured players with interesting war experiences were Bert Shepherd and Phil Marchildon. Both were prisoners of war in Europe. Marchildon, a Canadian, pitched for the Washington Senators before and after the war. During the war he was a tail gunner in a Halifax bomber that was shot down in the waters of Denmark’s coast. Shepherd, on the other hand, was a minor league player until he joined the Army Air Corps in ’43 as a bomber pilot. He, too, was shot down in combat, losing the lower part of his leg. He was part of a POW exchange that sent him back to the United States prior to the end of the war. He was hospitalized at Walter Reed where he met Clark Griffith, owner of the Senators. He was given a try-out and opportunity to play before the season’s end and actually did pitch 5 and 1/3 innings filling in on the losing end of blowout, giving up only one run. He was the only major league player ever to play as a leg amputee. Marchildon was less fortunate after his capture. He was placed in Stalag III in Poland and finally freed near War’s end by advancing British troops. His last pre-war season pitching record was 17-14 in 1942 for the A’s, to whom he returned after the war to win 19 games in 1947, and for whom he continued to pitch until retiring in 1950.

Along the way, there appears to be a certain amount of embellishment. For example, a rant at the home plate umpire in Chapter Eight, supposedly uttered to Leo “the Lip” Durocher, seems fantasized, because I would find it hard to believe it was preserved verbatim in 1942. The complaint is about a strike call, and in his outburst Durocher is credited by the author with dropping the f-bomb 14 times in eight sentences. There are quotation marks around the paragraph as with a direct quotation from a reliable source. Nevertheless, even if fabricated in this instance, the quote was a perfect imitation of Durocher’s speech on the field.

The author also tends to mix events and metaphors in the same paragraph. These involve both the war and baseball even though the events are not coupled in any way other than their inclusion by the author in the same chunk of text. When five of ten crew members survive a plane crash, he mentions the pilot’s batting average. Within any chapter the text might drift back and forth from an invasion to a pennant race or from a bombing raid to a home run. I would guess this is the author’s means of drawing a tighter relationship between the war and baseball, but often the reader is left with a sense of confusion. He also peppers the text with odd metaphors and similes such as referring to Red Schoendienst’s hair color as “a victory garden full of carrots” or mentioning that Greenberg at one point felt like “shit on a shingle,” an Army metaphor most frequently used for chipped beef on toast rather than a simile about personal feelings about one’s condition. Discussing the signing of the surrender document on the U.S.S. Missouri, he states “MacArthur was not the kind of general who spiked the ball.” All these examples strike me as the author’s attempt to amuse with colorful language, but some may find it ineffective and gratuitous.

I have a good friend who is a recent retiree from the English faculty of Australian National University in Canberra and an avid San Francisco Giants fan. When I told him in an email about this book and its length, he marveled that the topic would require that much text. After completing my first of three readings of it, I tended to agree that it could have been shortened considerably by the exclusion of some ‘stories’ or by reducing the discussion of a given subject. For example, there are several instances in the book when the text seems unnecessarily drawn out, as when Hank Greenberg hits a home run in Chapter Twenty-six during the ’45 pennant race. The episode takes the author four paragraphs to discuss Nelson Potter’s pitching; the home run, alone, from the swing of the bat till it clears the fence takes a full paragraph. A similarly lengthy account is given in the same chapter of Pete Gray running down a fly ball. I imagine these were the author’s attempts to capture the excitement of the action so the reader would be more thrilled in the reading. However, it stuck me as a bit artificial and unnecessary.

Some minor errors in the book escaped the editor’s correction, including the misspelling of the name “Prothro” that appeared as “Protho” in several places in the text as well as the index, and one incidence of a type-setting error printing “Mark” instead of “Mack,” the surname of the Philadelphia A’s owner. In Chapter One, the statement about the “factory horn bellowing at nine and five” should more accurately have read “bellowing at seven and three,” as anyone from the industrial Midwest would know. We can forgive these gaffs along with a statement about Phil Marchildon’s flight officer’s suit being royal blue like “his royal-blue Philadelphia Athletics hat.” The A’s color is green, and I think it was green in 1942 as well. The reviewer saw an old A’s uniform at the Baseball Hall of Fame that had a green, not blue, A on the front.

For any avid baseball fan or anyone interested very specifically in World War II history, I recommend this book as light, entertaining, and informative reading. Klima’s sportswriter style grows on you after awhile, and one becomes accustomed to the topical bouncing around between war, baseball, politics, and whatever else that unbalances Klima’s narrative. But for someone whose interest tends toward a more academic, data-based approach to the writing of history, the book might fail to satisfy.