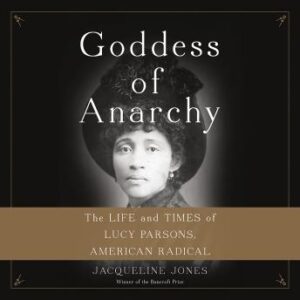

Lucy Parsons is no longer a household name, but in the 1890s she was well-known among radical activists and the police, civic leaders, and businessmen who kept close watch on them. The wife of notorious anarchist Albert Parsons, who was executed for his alleged participation in the 1886 Haymarket affair, she was a radical celebrity in her own right. Long after Albert’s execution, she carried on his memory and the anarchist message as a staunch radical. Her career as a writer, orator, and agitator overlapped with major labor conflicts in U.S. history from the Great Upheaval in the 1870s through the Red Scare of the 1920s and the Great Depression in the 1930s. Born into slavery, she never discussed race; a woman of great talent and skill whose liaisons moved her beyond the social confines of Waco’s colored community into a world where she met Albert Parsons, moved to Chicago, and embarked on a career which vaulted her to national notoriety. Lucy Parsons is long overdue for a serious biography, and Jacqueline Jones, an accomplished historian who holds the Ellen C. Temple Chair in Women’s History and the Mastin Gentry White Professorship in Southern History at the University of Texas at Austin, has given us the careful study she deserves. Goddess of Anarchy not only recovers Lucy’s story, it provides a window onto the richness of Chicago’s radical culture and a broader national network of labor activists in the early twentieth century.

Born 1851 as Lucia, and in Virginia to an enslaved woman named Charlotte, she was twelve when in 1863 Dr. Thomas Taliafero packed up his household and slaves—including Lucia, her two younger brothers, and mother—to move to McLennan County, Texas. The countryside there proved a dangerous place for freed people of color following the end of the Civil War. Nearby Waco attracted both Whites and Blacks in the years following the war and was more open and amenable to racial and party politics. There Lucia was able to attend school, one of the few girls over the age of sixteen to do so. Jones writes that sometime between December 1867 and November 1868, Lucia became pregnant. The child died mysteriously as a toddler and the father was unknown, but several men had come into Lucia’s life and at least one considered her his wife. Albert’s story intersects with Lucia’s when they most likely met in the small circle of Waco Republicans. By this time, Albert had renounced his Confederate past and had become immersed in Republican politics as a newspaper correspondent, orator, and government official. Jones’s meticulous research on the lives of Lucia and Albert in Waco, and within Texas Republican politics, makes fascinating reading.

Born into slavery, she [Lucy Parsons] never discussed race; a woman of great talent and skill whose liaisons moved her beyond the social confines of Waco’s colored community into a world where she met Albert Parsons, moved to Chicago, and embarked on a career which vaulted her to national notoriety.

In 1873, Lucia followed Albert to Chicago. Leaving Waco meant shifting her identity as a former slave, a woman with a complicated sexual past, and mother who had lost a child. These facts defined her in the south, but were unknown outside Texas. To mark the transition to a new life she changed her name to Lucy, and her origin story, during the journey. Settling in the German immigrant community on Chicago’s north side, she and Albert immersed themselves in a new life of labor radicalism. Both became committed labor activists after their move to Chicago. Albert ran for office several times, and he and Lucy were active in state and even national third-party political conferences. But the election of Carter Harrison, a Democrat able to woo Chicago’s working-class voters, including those in Lucy and Albert’s radical circles, turned them against the ballot box forever. Following Harrison’s election they looked to the message of Johann Most, who believed that spectacle and acts of violence, the tools of anarchists, would call forth the masses to throw off the tyranny of their masters. After Albert ran one last time in 1880, he disavowed politics. Lucy would never vote.

Jones identifies Lucy’s 1884 publication of “A Word to Tramps” as the turning point in her worldview and her career. Parsons argued that individuals might take dramatic action to bring justice to an immoral world, setting the stage for her later embrace of anarchist action. With this publication, she also “played the press well” as Jones explains, refusing to moderate her language and thus seizing the attention of Chicago readers of all backgrounds. Lucy’s ability as a writer and her sense of how to gain public attention marked both their careers; she and Albert would continue to cultivate their radical personas in the press and in public oration, claiming the importance of free speech. Jones deftly handles Albert’s relationship with the press and police in the years and days leading up to the Haymarket incident. When the smoke settled and Albert was imprisoned, Lucy was left with two young children and an anarchist ax to grind; she took to the speaking circuit to raise funds, first for Albert’s appeals and then for her own survival. Even so, Lucy was an accomplished seamstress and had previously supported the family. She need not have continued the grueling pace of travel, threats, and several arrests. Jones captures Lucy’s devotion to maintaining the martyred status of the executed Haymarket convicts. In death, they became celebrities, remembered through the pamphlets, books, and items Lucy and others sold at labor events and over the next decades of Lucy’s speaking events. The event, trial, and eventual execution are long-remembered among radicals for what many believed constituted a miscarriage of justice. Jones handles this period deftly, arguing that Lucy was the key to this memory and that the themes of oratory, free speech, and celebrity explain the impact of Lucy’s life, as she spent nearly fifty years after the Haymarket maintaining its memory as a touchstone of American radical politics.

Although a biography of Lucy, the first half of the book largely depicts Albert’s life, perhaps because Albert, a White man and a former Confederate soldier and political figure in Texas and Chicago, left a more visible historical trail than did Lucy, a former slave, and seamstress.

Despite her public profile, Lucy Parsons is a difficult subject for a biography. With few remaining letters and no diaries or other materials documenting her interior life, her motivations for many of her life decisions require careful interpretation from a deep knowledge of both the existing sources and the historical context in which she lived. Jones dug deeply into the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands at the National Archives and Records Administration, the Haymarket Affair Digital Collection, and especially into newspapers across the country to craft Lucy and Albert’s story. Although a biography of Lucy, the first half of the book largely depicts Albert’s life, perhaps because Albert, a White man and a former Confederate soldier and political figure in Texas and Chicago, left a more visible historical trail than did Lucy, a former slave, and seamstress. Lucy’s public life and high profile as the wife of the most famous Haymarket martyr emerged after their move to Chicago and Albert’s conviction. Both existing sources and her private motivations must be interpreted through the decisions she made to take up a relationship with Albert. Jones is at her best as a sensitive historian careful to explore the full range of possibilities for Lucy’s decisions. In doing so, she offers her readers a rich picture of Waco, a city that was decidedly southern but politically complex and racially fluid during Reconstruction. Chicago similarly was a welcoming place, with its high numbers of immigrants. Both places made possible Lucy’s recreation of her background; indeed she was sometimes depicted as of Mexican or Native American origin. Jones has pieced together a compelling biography of a complex woman, neither beholden to the conventions of her historical context nor entirely free of them.

Jones is at her best as a sensitive historian careful to explore the full range of possibilities for Lucy’s decisions. In doing so, she offers her readers a rich picture of Waco, a city that was decidedly southern but politically complex and racially fluid during Reconstruction.

Of various identities and stories Lucy might have told throughout her life—about her racial past which included memories of Black slavery and claims of Mexican and Indian origin, her gendered experiences, her intersectionality—she presented herself as a spokesperson of the laboring classes, an identity that would have had wide appeal. Yet Jones also notes that she rarely attended to the differential experiences and treatments of African Americans, which is a curious choice that deserves more attention. Did Parsons whitewash her story purely for her own personal reasons—to maintain privacy about her past or speak with the power that an ambiguously White racial identity was able to afford her? Or because ideologically she did not think race mattered to the radical cause? It still remains a mystery why Lucy failed to develop a racial analysis throughout her entire career. Her decision to commit her son to an asylum, where she largely forgot him, is also puzzling. The book might have been richer still if Jones had spent more time considering these choices, along with her various depictions of Mexican and Indian background across her career.

This is biography of the sort so rich, yet challenging to write. It requires a deep understanding of the historical context and the interplay between the individual and her world. Jones has previously written several books exploring the intersection of race, labor, and women’s history; here she marshals beautifully these histories to examine Lucy’s life through a series of overlapping narratives—Albert’s political career, Chicago’s radical history, African Americans in the Windy City, national and international contests between old-guard anarchists, Wobblies, and communists. The result is a fascinating story of an important figure in American radical culture, the issues that animated labor activists in the late nineteenth century, and the critical role of free speech and the use of celebrity in the business of maintaining that culture. Jones’s device of writing deep contextual histories around what is known of Lucy’s biography not only makes for fascinating reading on industrial, urban workers from the 1880s-1930s; it makes the book possible.