As P.J. Travers famously noted in Peter Pan, all children (albeit one) grow up. How they do it, however, is less uniform. Some retreat into silence, others rage or turn violent. Still others harden themselves against an unfair world. These transitions have been written about realistically and empathetically by countless young adult authors. Others have invoked a bit of magic to animate a decidedly unmagical developmental phase.

Two 2014 Newbery finalists, Doll Bones and Flora and Ulysses, take the latter approach. Both books are adventure stories, and their sheer excitement will appeal to younger readers who might not yet have experienced growing pains. Older readers will still love the adventure, but also identify with each book’s portrayal of the push and pull between childhood and adulthood. Whether a reader prefers one book over the other will likely depend not only on literary tastes, but on how he or she is handling adolescence.

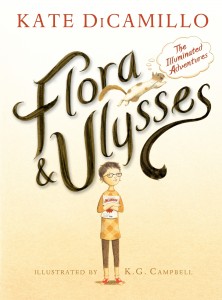

Lighthearted and whimsical, Flora and Ulysses is drawn in the exaggerated personalities and language of the comic books it riffs on. The book, which was the 2014 Newbery Medal winner, showcases a sarcastic, skeptical young girl who, as she matures, confronts emotions she has learned to suppress. In the process, she learns how to hold on and hold tight to the people she loves. Doll Bones, a Newbery honor book, focuses on three characters teetering on the brink of full-blown teenagehood. Although the book, at its core, is about learning to let go of childhood, Holly Black’s trademark macabre turns what could be a hackneyed theme into a wonderfully thrilling yet incredibly creepy read. Letting go and holding on—two different responses to the universal phenomenon of growing up.

Flora and Ulysses, by contrast, will appeal at once to any child who has ever felt misunderstood. We first meet Flora alone and brooding in her room, her heart hardened against hope, wonder, and other childlike idylls. A self-proclaimed cynic, she claims not to care about her parents’ divorce, or her father’s melancholy, or even whether her mother loves her or not. Instead, she loses herself in comics and superheroes—“idiotic high jinks,” according to her mother—and reads up on how to survive various calamities, including seizures, choking, and what to do if stranded at the South Pole. For Flora, misfortune must be expected and dealt with practically as possible. Her mantra is “Do not hope; instead, observe,” a phrase intended to protect herself against further disappointment. Still, she is more spunky than surly, and makes for a lovably misanthropic heroine.

It is almost like aging in reverse: a girl who has toughened before her time learns to embrace the wonder, joy, and comfortable dependency of childhood. The book’s final scene finds Flora on a couch surrounded by her parents and friends, a far cry from how we first found her in the opening pages.

But Flora’s world begins to take on the sheen of The Illuminated Adventures of the Amazing Incandesto—her favorite comic—when she takes in a squirrel named Ulysess, who has acquired magical powers after being sucked into a vacuum. Ulysses can fly, understand English, and even type, with a predilection toward expressing his thoughts through poetry. Although Flora has longed for just this type of superheroic adventure to supercharge her life, the intense bond she and Ulysses develop—coupled with the squirrel’s rapturous poetry about doughnuts—reveals that it isn’t zany exploits that make life rich, but rather its simple pleasures and emotional attachments. Ulysses possesses the wide-eyed innocence and wonder usually associated with children, and serves the same purpose that children often do in literature: awakening adults (or in this case, a sardonic adult-in-training) to what truly matters in life.

As one escapade involving Ulysses follows another, Flora recruits her father, a string of neighbors, and eventually even her villainous mother, for help, bolstering her relationships with each along the way. By the end of the book, Flora is able to shed her cynical shell and let herself acknowledge her feelings of hope, love, and perhaps most difficult of all, her desire to be loved too. It is almost like aging in reverse: a girl who has toughened before her time learns to embrace the wonder, joy, and comfortable dependency of childhood. The book’s final scene finds Flora on a couch surrounded by her parents and friends, a far cry from how we first found her in the opening pages.

In Doll Bones, the trajectory of the characters’ emotional lives is similarly shaped by an anthropomorphic creature, this time in the form of a doll. Zach, Poppy, and Alice have grown up together, using a rotating cast of dolls and action figures to act out ongoing adventures with pirates and mermaids. But now that Zach is 12, his father decides he is too old for such games, and throws out Zach’s toys without asking, casting off a childhood Zach isn’t quite ready to shed. He explodes at his father in helpless fury, and promptly quits the game, too proud and embarrassed to tell his friends about his loss.

While Zach attempts to sort through his turmoil, Poppy becomes convinced that one of their dolls, the Queen, is made from the bones of a little dead girl, whose ghost has asked that the doll be buried with the girl’s family. And so the trio sets out on one last adventure to find the girl’s gravesite. This time, however, there is no role-playing, just three pre-teens who must use their own resources to navigate the physical and emotional difficulties that arise from their quest. While Flora drew on the adults in her life to help her find Ulysses when he is kidnapped, Black’s characters rely only on themselves, sneaking out of houses, pooling their change for bus fare, and avoiding anyone who might report runaway teens at all costs. Though the purpose of the quest—to bury a plaything and its concomitant ghost—is childlike in nature, the journey itself is a clear and defiant means of asserting their burgeoning independence.

But still, their path toward teenhood, like most paths, is far from linear. Even as they travel to the cemetery, Alice and Zach continually waffle about whether to believe Poppy, which is as much about a childlike willingness to suspend belief as it is about the actual truth. For Zach especially, the veracity of the situation takes on greater significance. If ghosts were real, “then maybe the world was big enough to have magic in it. And if there was magic,” the narrator tells us, “then maybe not everyone had to have a story like his father’s, a story like the kind all the adults he knew told, one about giving up and growing bitter.”

Had they been a little older, Poppy would have had her license and could have driven the few hours to the cemetery with little fuss. But that would have made for a pretty poor adventure, and would have deprived Zach of the maturation he experiences along the way: By the end of the book, he realizes he is ready to let go of his figures, and even asks Alice out on a first date. This is indeed a story that could only happen to tweens, and as such, will make it all the more loved by its readers.

Taken together, these books show us what most adults already know: that kids handle adolescence differently, and that growing up is by turns confusing, hilarious, and yes, sometimes scary. But in just the right light, and often only in retrospect, it is nothing short of an adventure.